By Peter Mecca

She was not appealing and handled like a long-haul tractor/trailer with 18 flat tires. Historically treated as the red-headed stepchild of heavy bombers in World War II, especially when compared to the sleek and popular B-17 Flying Fortress, the B-24 Liberator was still a rugged aircraft and destined to become the most produced American bomber in history. More than 18,000 were built during the war, approximately 70 percent by the Ford Motor Company.

She had her faults: a tendency to catch fire; if required to ditch or belly land, the high fuselage-mounted “Davis wing” habitually broke apart the fuselage; poor formation-flying characteristics; and Liberator pilots had a reputation for having big biceps from wrestling non-stop with clumsy control capabilities. But the ugly lady had good attributes too: a higher top speed than B-17s, greater combat range, a heavier bomb load, and a higher service ceiling of 28,000 feet.

Even damaged, she brought home many an airman. Brigadier General and award-winning actor Jimmy Stewart often piloted a B-24, once over Berlin. Former Speaker of the House Jim Wright served as a bombardier on a B-24 in the Pacific. Senator and 1972 presidential hopeful George McGovern piloted Liberators over Italy. Congressman, Secretary of the Interior, author, and conservationist Stewart Udall flew on Liberators as a waist gunner, plus famous Olympic runner Louis Zamperini served as a bombardier on B-24s. In the digital era, the video game “Call of Duty: Big Red One” mimics gun turrets and the bomb-sight of B-24s to engage armchair warriors.

This is the story of only one of those 18,000-plus Liberators, a brand new B-24 recently arrived at Soluch Field near Benghazi, Libya. Her crew was also new, and like the B-24, would be flying their first, and last, combat mission. The Liberator and her nine-man crew were assigned to the 376th Bombardment Group, 514th Bomb Squadron, the date April 4, 1943, the B-24’s given name Lady Be Good.

Probably coping with an emotional mixture of excitement and anxiety, the pilot of Lady Be Good, 1st Lt. William Hatton, and his copilot, 2nd Lt. Robert Toner, pushed the four Pratt & Whitney engines to full throttle for takeoff. The B-24 Liberator lumbered down the Soluch airstrip and was soon airborne over the Mediterranean. One of the last to take off, Lady Be Good almost immediately experienced poor visibility and sandy winds, which kept her from joining the formation of 12 other Liberators en route to bomb Naples, Italy. Lady Be Good and her crew were on their own.

Nine of the B-24s aborted the mission after developing engine trouble caused by the swirling sands of the Libyan Desert during takeoff. Four continued. Lady Be Good arrived over Naples at 7:50 p.m. at an altitude of 24,900 feet, found the target socked-in by bad weather, then turned for home. The crew either dumped their bombs in the Mediterranean or hit a secondary target en route back to Libya. At 12:12 a.m., the pilot, Lt. Hatton, radioed Soluch airfield for directional assistance, stating the aircraft’s automatic direction finder was no longer working. That was the last contact with Lady Be Good. A search and rescue mission was eventually launched from Soluch, but no trace of the crew or aircraft could be found so the rescue mission was called off… there was still a war to be fought and won.

Lady Be Good became a war statistic as did her crew, and the statistics are staggering. The U.S. lost 43,583 aircraft overseas, of which 22,918 were lost in combat. Another 13,872 planes were destroyed inside the continental U.S. while on training missions and almost 1,000 airplanes disappeared while en route to overseas destinations. During the height of the war, an average of 200 flyboys died per day. Almost 12,000 were and still are missing and presumed dead. It’s easy to understand why Lady Be Good and her nine-man crew became a mere footnote of the air war.

More than 15 years later, in November 1958, a British oil exploration team from the D’Arcy Oil Company (later to become BP) spotted aircraft wreckage while conducting an aerial survey over the Libyan Desert near the edge of the Sand Sea of Calanscio. The exploration team’s position was roughly 440 miles from Soluch, Libya. The sighting was reported to American authorities at Wheelus Airbase on the coast of Tripoli, but no attempt was made to inspect the wreckage since there were no records of any American aircraft lost in that area. The position of the wreckage was marked on the maps of the oil exploration team since another oil assessment mission was scheduled the following year in the Calanshio Sand Sea. There was another sighting in June of that year.

A British oil surveyor along with two geologists spotted the wreckage on Feb. 27, 1959, and plotted the coordinates. Wheelus Airbase finally dispatched a recovery team to the site on May 26, 1959. On-site, the recovery team confirmed the hand-painted words on the starboard front side of the forward fuselage: Lady Be Good.

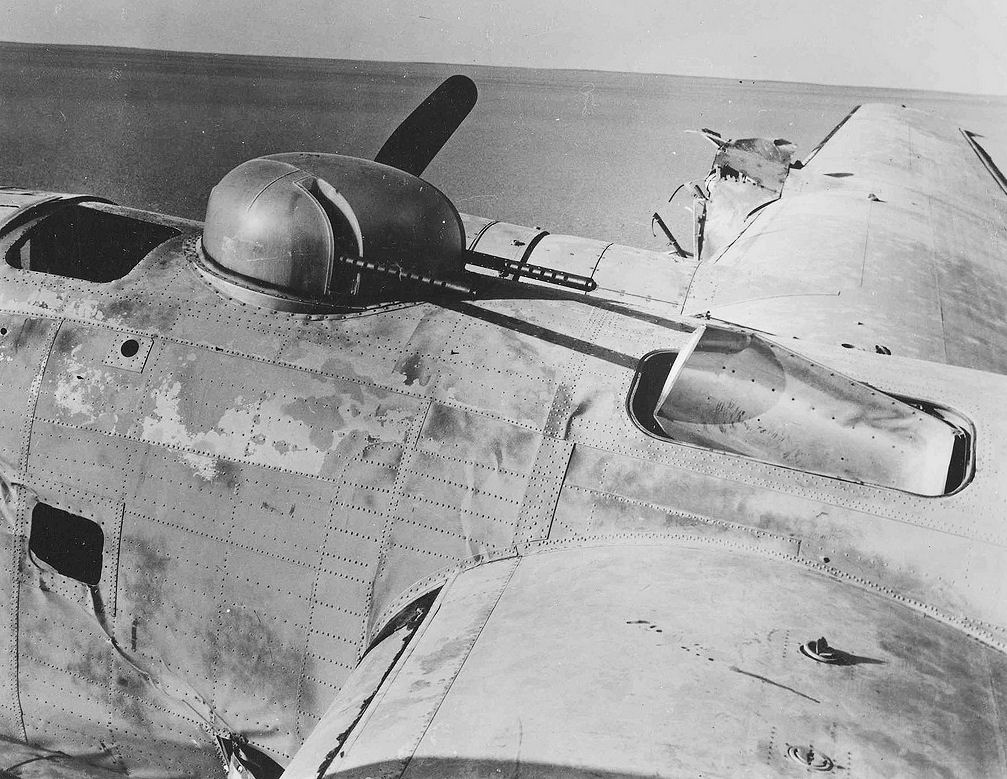

The Liberator had skidded almost 700 yards; the fuselage broke in half behind the wings, and a technical inspection discovered she had landed on the power of one engine. Due to the desert’s excellent preservation capabilities, Lady Be Good was in an amazing state of preservation. The coffee in a Thermos bottle was still drinkable and many of the aircraft’s .50 caliber machine guns were in working condition and actually fired by team members. The radio worked, some food and supplies were intact, and the log of navigator Lt. D.P. Hayes was found with his final entry posted over Naples. No human remains inside or outside of the aircraft, plus an absence of parachutes indicated the crew had bailed out. In other words, Lady Be Good had landed herself.

Additional searches in 1960 discovered the remains of eight of the nine-man crew. Evidence revealed they had bailed out about 16 miles north of the landing site of Lady Be Good. Eight survived the bailout. Unknown to the eight, the ninth crewmember, Bombardier Lt. John Woravka, had died when his parachute failed to open. The eight survivors decided to walk north, towards Libya; had they journeyed south the Lady Be Good awaited them with provisions and supplies and a working radio to call for help. Still further south, within walking distance, the Oasis of Wadi Zighen awaited their life-saving visit.

A personal diary discovered in the pocket of the co-pilot, 2nd Lt. Toner, revealed details of their desert trek and suffering. They shared one canteen of water for eight days, left behind clothing articles, Mae West life vests, footwear, parachute material, and other items to mark their path, and came to a pause about 81 miles north of Lady Be Good. Five remained while three others continued north in search of help. Staff Sgt. and gunner Guy Shelley’s remains were discovered 24 miles north of the recovered five bodies; flight engineer Harold Ripslinger’s remains were found 27 miles north of Shelley’s remains. Ripslinger had walked 200 miles from the crash site before the desert took his life. The body and remains of Staff Sgt. Vernon Moore, the gunner, has never been found.

Official report of Graves Registration: “The aircraft flew on a 150-degree course toward Soluch Airfield. The craft radioed for a directional reading from the HF/DF station at Benina and received a reading of 330 degrees from Benina. The actions of the pilot in flying 440 miles into the desert are indications that the navigator probably took a reciprocal reading off the back of the radio directional loop antenna from a position beyond and south of Soluch but ‘on course’. The pilot flew into the desert, thinking he was still over the Mediterranean and on the way home.”

In simpler terms, the pilot and crew believed they were still over water when in fact they had overflown their home base of Soluch and into the unforgiving desert. To a novice pilot, the desert can spookily resemble a body of water.

Lady Be Good landed herself on one engine and awaited her crew with life-saving provisions. She had done her job. Fate, however, turned on the Lady Liberator and denied her the opportunity to save her men. In a strange quirk of fate, perhaps Lady Be Good desired to remain in the Libyan Desert with her crew instead of being salvaged and chopped up for spare parts.

A few parts are on display at a variety of museums, but in the air, Lady Be Good’s carved-up body parts were not happy. A C-54 cargo plane had several auto syn transmitters installed from Lady Be Good – crew members had to throw their cargo overboard to land safely after the propellers developed serious difficulties. A C-47 with a Lady Be Good radio receiver crashed into the Mediterranean. An Army de Havilland Otter received an armrest from Lady Be Good, the aircraft crashed into the Gulf of Sidra. Very few traces of the de Havilland washed ashore, one being the armrest of Lady Be Good. An Army issue Elgin A-11 wristwatch found near the remains of a Lady Be Good crewmember is on display at the Army Quartermaster Museum at Fort Lee, Va. It’s still ticking, and accurate to within 10 seconds each and every day. The Ghost Liberator Lady Be Good can still be counted on.

As a young boy, I read a brief article on the back pages of a local paper on the discovery of Lady Be Good in 1959. Details were sorely lacking. Like so many of our missing planes and flyboys and Marines and ships and sailors, Lady Be Good only registered back page news. I had always wanted to know the real scoop. Curiosity got the best of me. After extensive research, her story unfolded. Now you and I both know.

Article by Peter Mecca

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran. To read Pete’s stories visit www.aveteransstory.us

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.