By Casey Asher – USAF Officer, Reenactor, and Collector

As a kid, I loved flipping through my dad’s extensive library of books on the Army Air Corps in WWII. The images of confident young fighter pilots posing next to their sleek, aluminum aircraft captured my imagination. But it was their gear—especially those classic leather USAAF flying helmets—that truly fascinated me. I dreamed of owning one someday. Flying helmets hold a special place among militaria collectors, and over the years, I’ve been fortunate to own several. Whether you’re interested in these helmets for display in a man cave, for their historical significance, or for use in public education through living history events, it’s important to understand both their history and what to look for as a collector.

From Canvas Caps to Combat-Ready Gear

During World War I, U.S. Air Service crews wore a variety of headgear—from simple leather caps and canvas flight helmets to hard-shell football helmets. After the war, the U.S. military began to standardize Aircrew Flight Equipment (AFE), leading to the development of helmets tailored to specific operational needs, climates, and oxygen systems.

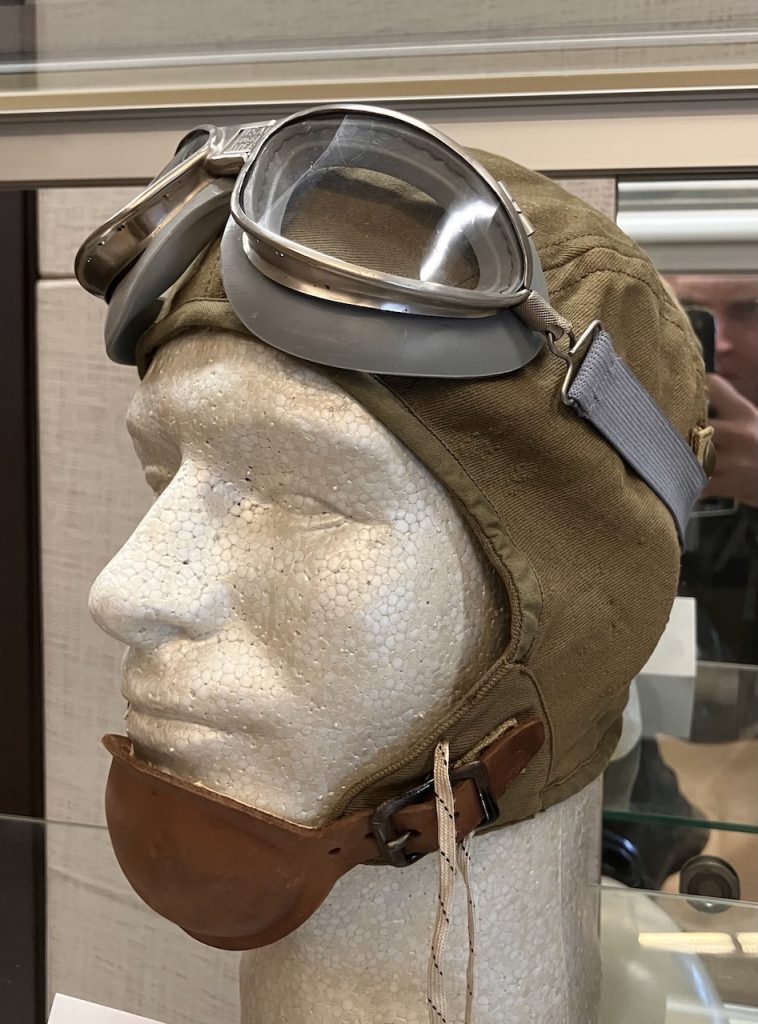

The A-8 and B-5 flight helmets were introduced in the early 1930s. The A-8, made from olive drab wool twill with shearling ear pads, was suited for warm-weather, low-altitude flying. The B-5, by contrast, was leather with full shearling lining, offering better protection in cold, high-altitude environments. Both had a leather chin cup with side buckles. Later revisions—resulting in the A-9 and B-6—eliminated the chin cup in favor of a fur-lined chinstrap and added wire hook tabs for oxygen mask attachment.

At this stage, none of the helmets were factory-equipped for radio communications, as aircraft used varied systems. Trainers often relied on the Gosport tube system—basically hollow tubes connecting the instructor and student—leading to the integration of metal tube fittings in some helmets. Combat aircraft, however, used R-14 radio receivers, which were housed in sewn-on leather ear cups or foam rubber pads from early HS-23 headsets. Later versions also included snaps to secure oxygen masks such as the A-10, A-13, and A-14 series. A-8 and A-9 helmets saw widespread use in training and in combat zones with warmer climates. The B-5 and B-6 were preferred in colder regions, becoming the go-to headgear for ETO (European Theater of Operations) crews up through early 1944.

Influence from the RAF and Evolving Design

When AAF crews arrived in England, many took notice of the RAF’s superior Type C leather helmets. These were warmer, more comfortable, and featured innovations like chamois-covered donut-shaped earpieces. AAF fighter pilots especially favored these helmets, and they occasionally made their way into bomber crews as well. These desirable features influenced later U.S. designs.

Midway through WWII, the U.S. introduced improved standardized helmets like the AN-H-15 for warm climates and the A-11 and AN-H-16 for cooler conditions. These featured large, stiff rubber ear cups for ANB-H-1 receivers and chamois-covered cushions for comfort and noise insulation. These designs quickly replaced earlier models and became the standard across both Army Air Forces and Navy units by the war’s end.

Collecting Considerations: Condition, Rarity, and Reproductions

For collectors, the value of WWII flying helmets depends on three main factors: condition, size, and provenance. Leather helmets are especially prone to deterioration—dry rot and hardening are common in poorly stored examples. Among the most accessible for beginners are the A-9 and AN-H-15, which were produced in large quantities and remain relatively easy to find in good shape. Flight helmets with receivers installed command higher prices, and larger, wearable sizes are generally more valuable than smaller ones. Collectors often prize the B-6, particularly if it features wartime modifications indicative of combat use. The ultimate prize? A helmet with provenance—a clear connection to a known veteran. Name tags, inscriptions, or family lineage documentation can significantly increase both historical and monetary value. If the helmet has a confirmed combat history, even better.

Reproductions and Their Place

Reproductions are readily available and can be useful for reenactors or display use where original gear might be at risk. One of the most respected reproduction sources is Eastman Leather, known for its accurate B-5 and B-6 copies—so good, in fact, they’ve been used in numerous Hollywood films. These reproductions include authentic-looking tags and details that can easily pass for originals with light wear. Other manufacturers like Five Star Leather (Pakistan) offer mid-grade replicas of the A-9 and B-6. They’re decent but can be identified by their non-period tags. What Price Glory previously produced an A-11 replica with noticeable flaws such as an exaggerated AAF wing stamp and oversized rubber earcups. For those drawn to RAF gear, Soldier of Fortune makes a fair Type C replica, but the Sefton Clothing Co. version stands out as the most accurate and is often used in film productions.

wears the A-11 flying helmet popular late in the war. Photo by author

Final Thoughts

If the Masters of the Air TV series has sparked your interest in WWII flight helmets, I hope this guide helps you make a more informed—and more rewarding—choice. These helmets are more than collector’s items; they are artifacts of courage, craftsmanship, and aviation history. For further reading, I highly recommend Combat Flying Clothing by C.G. Sweeting. And for detailed photographs of authentic gear, visit the 303rd Bomb Group’s website at 303rdbg.com.