By Marty Steiner

We Americans make much of being home for Christmas. The song “I’ll Be Home for Christmas!” echoes from earbuds, department store sound systems, and countless other sources each holiday season. Yet during World War II, thousands of young men and hundreds of women found themselves away from home for Christmas—many for the very first time. They were stationed at military air training bases across the country, encountering unfamiliar regional accents, strange foods (okra, greens, yams, turnips, sweet tea), and fellow servicemembers from every corner of the nation. For others, it was a final Christmas spent with family before reporting to a military base and facing the uncertainties of wartime service. And for those already overseas, Christmas was often just another day under fire.

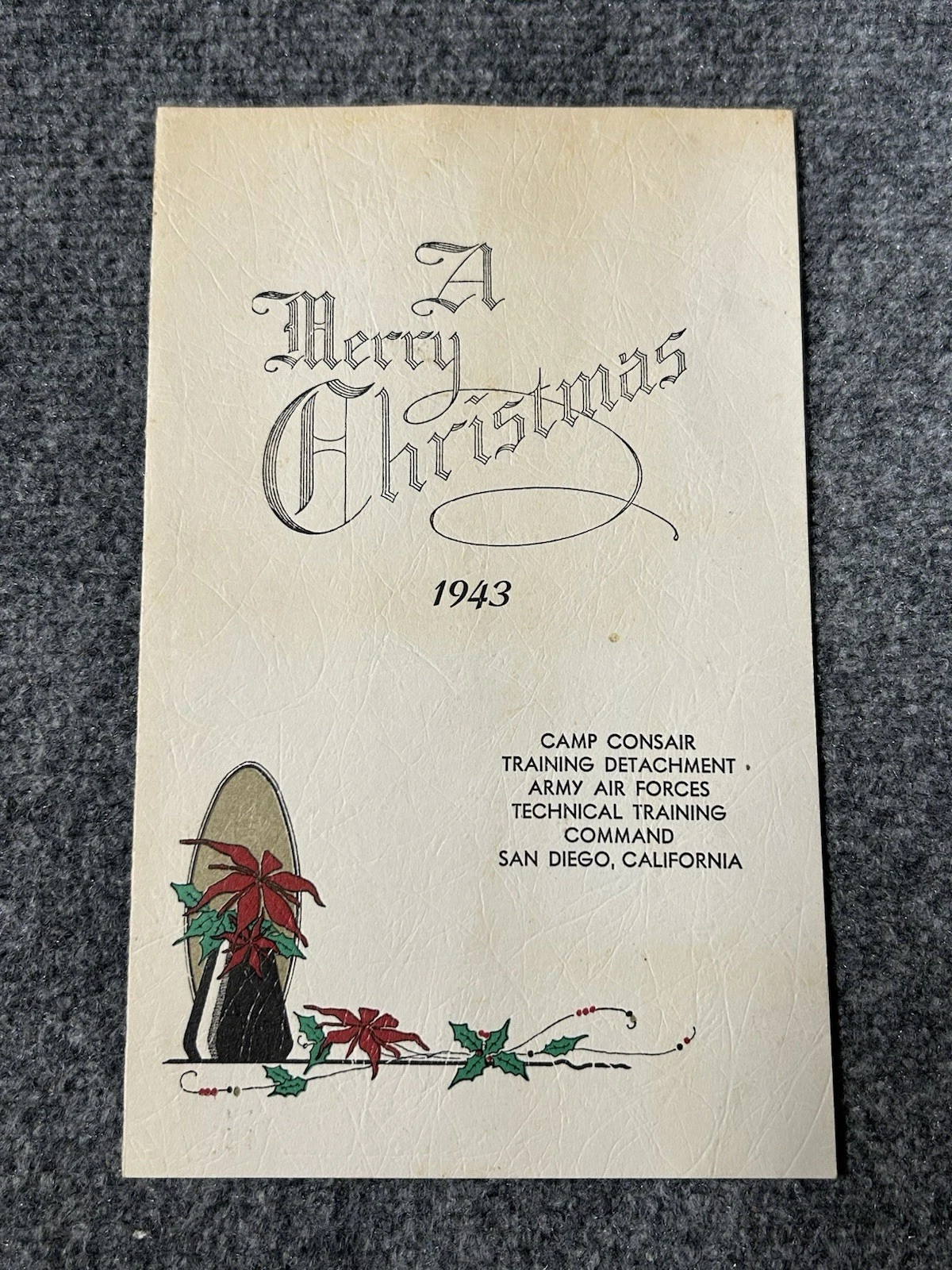

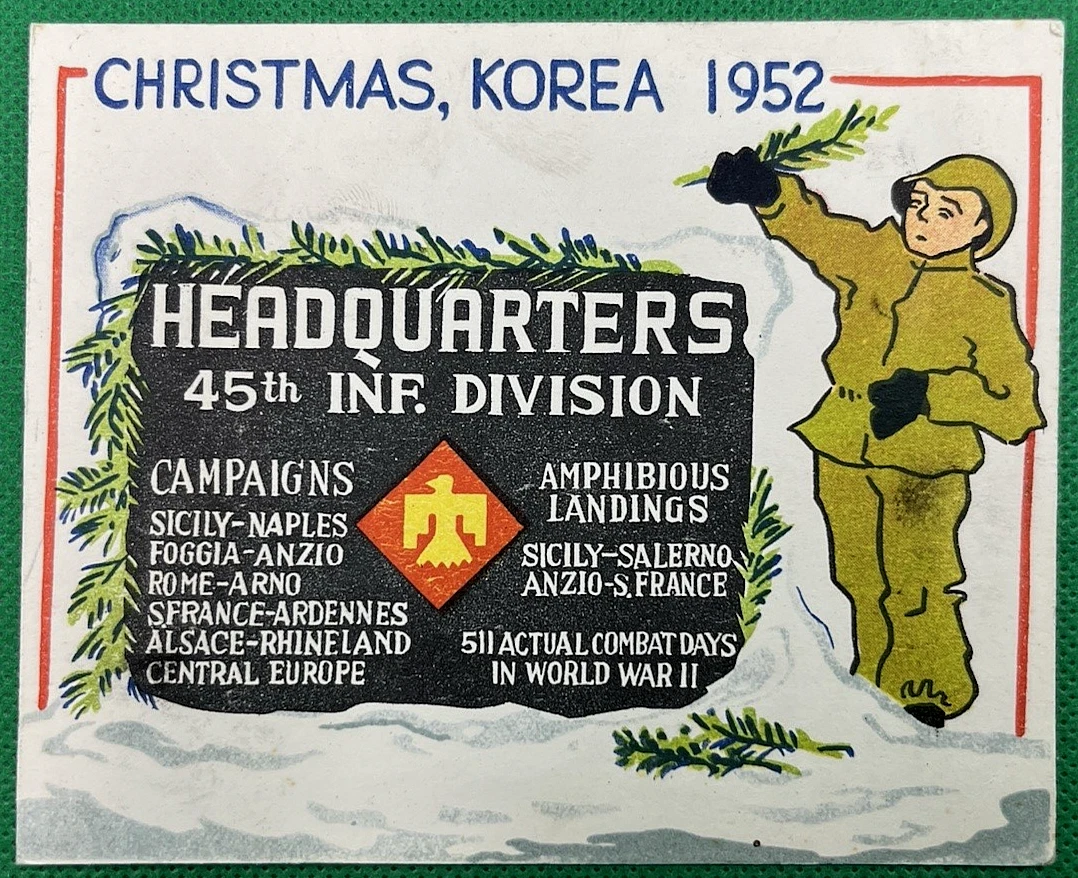

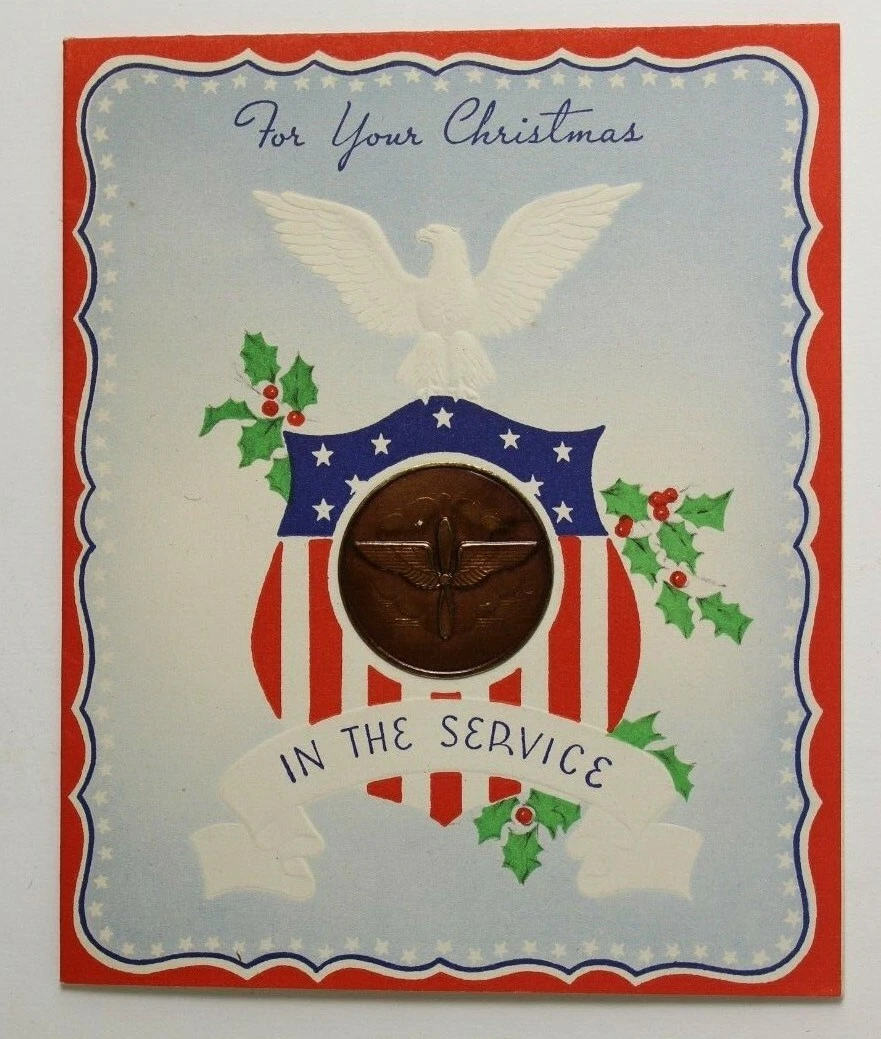

What could—or would—be done to celebrate the holiday in some comforting fashion? Each base and unit typically marked Christmas with a special dinner, modeled after a traditional American family holiday meal. Some locations also offered church services, musical performances, or opportunities to participate in local holiday events such as dances. Was this the first time servicemembers experienced the absence of family during the holidays? Not at all. Authentic reflections of this experience from various periods in American history can be found today in family scrapbooks, collectible memorabilia, and historical society or museum archives. A few genuine examples of these items, which take us back to Christmases past, are shown here. The items illustrated—and many others—are examples that can now be found for purchase online.

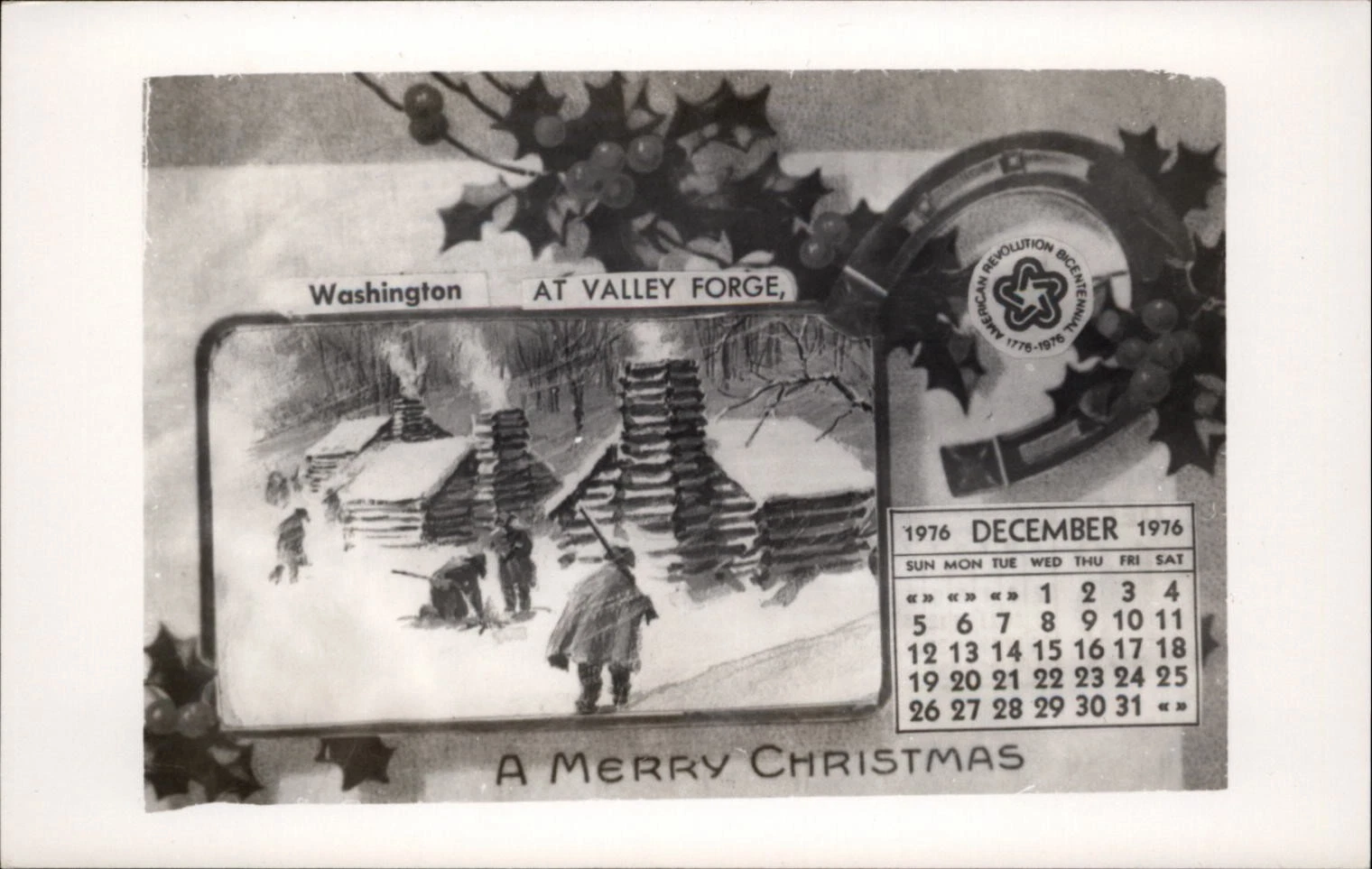

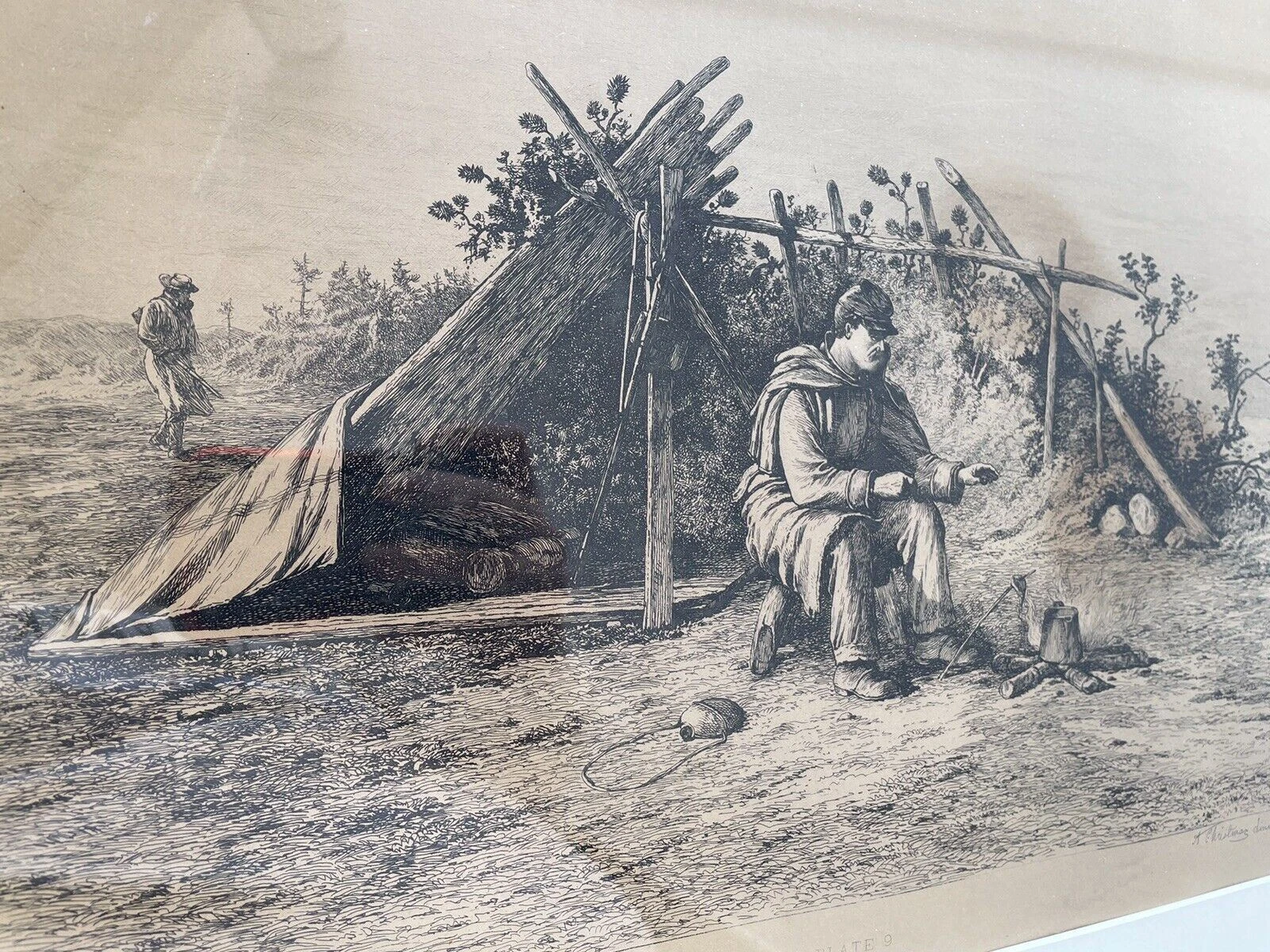

Christmas during the War for Independence, the American Revolution, has often been remembered through images of General George Washington kneeling in prayer on Christmas Eve. In reality, the Continental Army, wintering at Valley Forge, was hunkered down in crude shelters built from found materials, later replaced by rough structures made from trees cut in the surrounding valleys. Holiday communication was minimal, and there were no special meals or organized celebrations. Other conflicts—including the War of 1812 (largely fought offshore), the Civil War, and the Spanish-American War—were similar in how participants and their families communicated over the holidays. A small number of preprinted greeting cards and personal letters survive from these periods, but little evidence exists of the military providing organized holiday activities or special meals.

Perhaps it was a shared longing for home among the trench soldiers of World War I that led to the famous Christmas Eve truce of 1914. Soldiers who had been locked in brutal combat met in no-man’s-land, exchanged cigarettes, shared brief conversations, and even played a game of soccer before returning to their trenches to continue the war. In the years following World War II, the tradition of special holiday meals and events at military installations continued, along with the exchange of greeting cards. Program booklets from unit Christmas dinners often included menus and lists of assigned personnel. Examples from the postwar Occupation period, as well as from Korea and Vietnam, are still being discovered today.

Modern technology has dramatically changed holiday communication. Cell phones, the internet, and even 24/7 U.S. Postal Service lockers now connect servicemembers with loved ones almost instantly. Most military installations around the world offer multiple dining options, both military-operated and privately contracted. As a result, contemporary holiday cards and dinner programs tend to carry less historical or nostalgic significance than those from earlier eras. This brief overview of Christmas and New Year’s as experienced by America’s military across more than 250 years is presented as a tribute to those who serve far from home—and to those waiting for them.

Peace on Earth.