Driving through central Nebraska one will find miles of farmland, groves of trees on the banks of creeks and rivers, and open skies. Here, the tallest buildings are not glass-filled skyscrapers but grain elevators and water towers. But in Minden, Nebraska, just south of Interstate 80 and in the shadow of a row of grain elevators across the street and the railroad, there is an incredible collection of all manner of antiques, from historic buildings, cars, a steam locomotive, household appliances, and even airplanes. They can all be found in the Pioneer Village.

Like many collections, it all started with one man, and in the case of Pioneer Village, that man was Harold Warp. Born in a sod house near Minden on December 21, 1903, just four days after the Wright Brothers flew on the wind-swept sand dunes of Kitty Hawk, NC, Harold was the youngest of 12 children to Norwegian immigrant John Neilsen Warp and Helga Johannesen. Warp’s early life was beset with tragedy, as his father died when he was 3, and his mother when he was 11. The Warp children soon came to live with local relatives and family friends, or in Harold’s case one of his older brothers. While in high school, Harold invented a type of plastic film to allow sunlight to enter chicken coops while protecting the chickens from the cold, as the young man had observed that chickens were more productive in laying eggs during the summer months than in the winter months and attributed this to ample sunlight.

In 1924, the 20-year-old Harold Warp took his Ford Model T and $800 in savings to Chicago, where he and his brother John set up a storefront on Cicero Ave to produce and sell his newly patented plastic coverings, which he called Flex-O-Glass. Some 100 years later, Flex-O-Glass Inc., along with Warp Bros. and Warp’s Greenhouse Films, remains in business to this day, and is still family-run. His success in the plastics industry made the young orphan from Nebraska a wealthy man, yet even as he built the path for his family’s future, Harold was interested in preserving the past. He maintained his roots in Minden, and he and his siblings would reunite every Christmas at the family homestead near Minden.

It was at one such Christmas gathering in 1948 that Harold learned that the old one-room schoolhouse he and his siblings attended classes in was being sold in favor of a new school building. Wanting to keep it from being demolished, he put up the money to buy the old schoolhouse and move it to downtown Minden. After raising further funds to help restore nearby Fort Kearney, he hired a local construction company to build a new attraction to house his growing private collection of all manner of antiques. Opened in 1953, the museum has since become one of Nebraska’s biggest attractions, even after Harold Warp’s passing on April 8, 1994, at the age of 90. But among his many interests, aviation also played a role in Warp’s life, who learned to fly behind the stick of a Curtiss Jenny and was a Life Member of the OX-5 Club of America and a member of the Quiet Birdmen fraternal organization. His love of aviation is reflected in this museum as well, since there are several fascinating aircraft held in the collection.

No aviation-themed museum is complete without a replica of the Wright Flyer, and there is one here in Minden. According to the museum, it was constructed under the direction of H.P. Boen in Kobe, Japan in 1962, and was shipped to Pioneer Village in 1964 and placed on display the following year. Next to the Wright Flyer is an original Curtiss Pusher. This was the aircraft in which American aviator Charles K. Hamilton made the first round-trip flight from New York City to Philadelphia on June 13, 1910, with Hamilton being in the air for three hours and thirty-four minutes. After this historic flight, the aircraft was kept in storage in a barn in New Britain, CT. Harold Warp acquired the old Pusher in 1954 and had it shipped to Minden for display in the museum.

Another pioneering pre-WWI aircraft to be found in the halls of Pioneer Village is that first airplane to have been built and flown in the state of Iowa. The creator of this aircraft was Arthur John Hartman, who was born in Burlington, IA in 1888. On September 6, 1903, after being acquainted with balloons through his work at the Goddard Balloon Company of Chicago, Hartman soloed at the age of 15 in a balloon three months before the Wright Brothers flew their Flyer at Kitty Hawk. Over the next few years, Hartman would not only become a balloonist but would leap from his balloons as a parachutist at public events, and in 1907, he would construct and fly a 67-foot-long dirigible. However, even by this point, Hartman could see that the future of aviation lay in heavier-than-air aircraft, and this was confirmed to many when on July 25, 1909, Louis Bleriot crossed the English Channel with a monoplane designed by himself and Raymond Saulnier, the Bleriot XI. Finding a photo of a Bleriot XI in a newspaper, Hartman decided to build his own airplane based on the design of the Bleriot.

By 1910, the Hartman monoplane was completed, and on May 10, 1910, at 5:00am, its 21-year-old pilot took off for a short hop in the presence of five witnesses (Henry Boyle, William Rheinschmidt, Tom Green, Hamey Winkler, and Will Apligate) at the Burlington Golf Course. Reportedly, Hartman even converted the aircraft into a hydroplane, but this was a short-lived modification. Later, Hartman would surplus Curtiss Jennies after WWI, help establish the Southeast Iowa-Burlington Regional Airport, and remained active in aviation well into his seventies, when publications credited him as the world’s oldest active pilot. Hartman would also rebuild with his monoplane to where it was almost unrecognizable from its appearance in 1910. He replaced the two-cylinder, horizontally opposed Detroit Aero 25hp engine with a three-cylinder Szekely SR-3 45-hp radial engine, and in 1935, he changed out the wooden fuselage frame for a tubular steel one and removed the pulleys and cables for wing warping and added ailerons to the wings. These extensive modifications kept Hartman and his monoplane flying, with the civil registration N286Y, well into the 1950s! Though the fabric on the wings would be recovered in 1952, the structure of the wings, tail, and rudder remained original to 1910.

On June 19, 1955, the 67-year-old Hartman would take his monoplane up for one last flight before a crowd of some 10,000 spectators at Clinton, IA. Among the crowd were Iowa Senator Bourke B. Hickenlooper, the mayor of Clinton, Don R. Allison, Harold Warp, and the two surviving witnesses from Hartman’s original flight (Henry Boyle and William Rheinschmidt). After the flight was concluded, Hartman handed the plane over to Harold Warp for preservation at Pioneer Village in Minden, where it can be seen to this day, along with photographs of the aircraft, a statement written by Arthur J. Hartman, and a tachometer and an ice scale used by Hartman to measure the pounds of thrust generated by the engine before takeoff.

Displayed next to the Hartman monoplane is a rare Taylor J-2 Cub (N19250). Though similar to the Piper J-3 Cub, the J-2 was built by the Taylor Aircraft Company, established by brothers Clarence and Gordon Taylor, and was largely financed by oilman William T. Piper. Eventually, however, Taylor and Piper clashed over where the company should go, and Clarence Taylor left the company to form Taylorcraft Aviation, while Piper remained to reorganize the company as Piper Aircraft in Lock Haven, PA, after a fire burned down the original factory in Bradford, PA. The J-2 exhibited today at Pioneer Village was purchased by Harold Warp on July 10, 1969, from Gary Voth of Los Animos, CO.

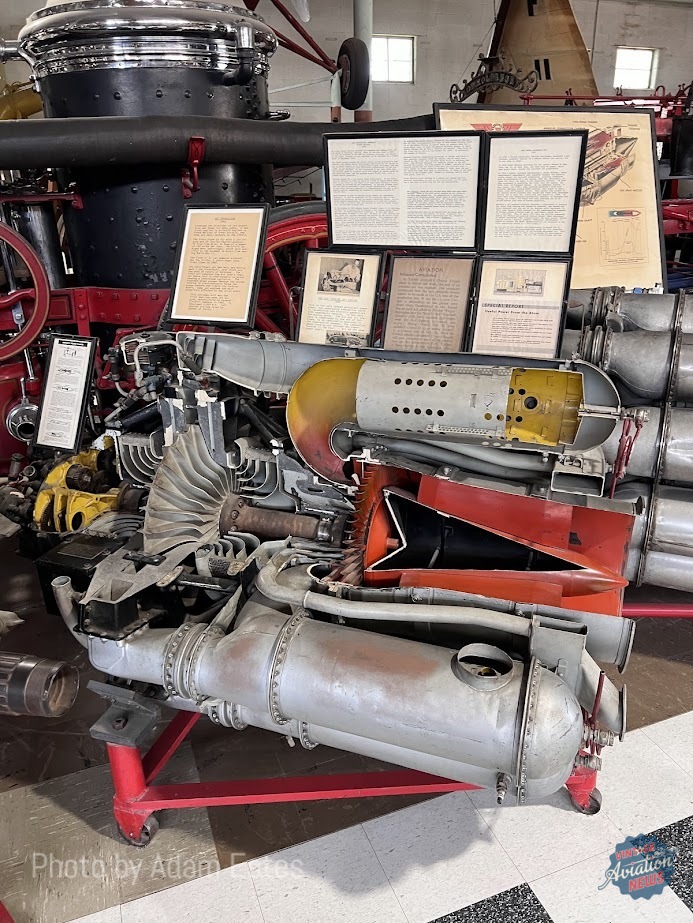

One of the rarest aircraft in the museum is an example of the first American jet aircraft, the Bell P-59 Airacomet. Developed using a licensed development of a jet engine designed by British engineer Sir Frank Whittle, the Airacomet was kept just as big a secret as the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb. Unlike the bomb, however, its performance was underwhelming, with a top speed of 413 mph that could be outpaced by contemporary piston aircraft such as the P-51 Mustang and the P-47 Thunderbolt. The Airacomet, however, was not a complete waste, as it was used for flight testing and when it was made known to the public, it was used to demonstrate how jet aircraft flew in comparison to propeller-driven aircraft. The example displayed at the Pioneer Village is serial number 44-22656, one of the 30 P-59Bs produced, representing nearly half of all 66 Airacomets built. The aircraft was used for flight testing in the states and was later brought to Purdue University in West Lafayette, IN for use as an instructional airframe. After its use at Purdue was coming to an end, Harold Warp recognized the historical significance of the jet, and had it placed on display at Pioneer Village, alongside two General Electric J31 (company designation I-16) turbojet engines, one of which was made into a cutaway for educational purposes.

Two aircraft flown personally by Harold Warp are also displayed in the museum, with these being an Erco Ercoupe (NC37100) and a Piper Apache (N1030P). The museum is also home to a WWI-era Curtiss JN-4D Jenny (NC1350), and a 1926 Swallow biplane (NC5070), built in Wichita, KS by the Swallow Airplane Company, both of which were powered by the Curtiss OX-5 90-hp V-8 engine, which was mass produced during the First World War, and was able in plentiful numbers not only for surplus Jenny trainers but for a variety of new designs that came out of the 1920s as well. The Jenny was also the aircraft in which Harold Warp learned to fly in 1927 after just six hours of instruction, before he turned around and taught his brother John to fly! The example in Pioneer Village was acquired by Warp in 1952.

Two radial engined, high-wing monoplanes of the 1920s and 1930s are also displayed here, such as a Cessna AW (NC8141), which Warp had acquired in 1962 after the closure of Chicago’s Sky Harbor Airport, and a Stinson SM-8A Junior (NC907W), which was flown to Minden in 1959 to join the collection. This Stinson is similar to one Warp himself had ordered from the Stinson company in 1929, which was completed on April 1, 1930 as the first to incorporate a Lycoming radial engine, and Warp himself would add oil-less bearings in the control assembly, cable guides and guards over the control assembly, parachutes built into the seats, and cabin ventilators among other modifications, though these are not present on the example flown into the museum for exhibition.

The Pioneer Village is also home to a few homebuilts and ultralights, such as a Heath Parasol. The Parasol was one of the first kit-built planes to see widespread success in American aviation, being initially designed by Edward Bayard Heath, an engineer and racing pilot, who designed the aircraft to be easy and cost-effective to build and to fly. They could also be modified to accommodate a number of engines, but the kit came with a modified motorcycle engine, the Heath-Henderson B-4, which had an output of 30-hp. The example at Pioneer Village is V-Parasol (aka a Super Parasol) was built in 1931 and flown by four owners by 1970, when it was restored by Jack Schnaubelt of Elgin, IL. Schnaubelt maintained ownership of the Parasol until January 1989, when it was purchased by the Harold Warp Pioneer Village Foundation.

Yet another homebuilt aircraft is a Chotia Gypsy ultralight (described by the museum as a Weedhopper Gypsy). Designed by John Chotia based on his two previous ultralight designs, the Weedhopper and the Woodhopper, but with a wooden cockpit pod, this example was built and flown by L. Duane Life of Wichita, KS, who ordered the kit in 1980, received it in April 1981, and had it test flown in June 1982, with fellow Wichita-based pilot Henry M. Dittmer at the controls. Powered by a Rotax 277 two-stroke 26 hp motor and painted as a British WWI fighter, Life flew it to several fly-ins and club contests, winning the Grand Champion and Outstanding Workmanship trophies at the 1982 contest in Beaumont, KS. The aircraft made its last flight on November 23, 1986, before being donated to the Pioneer Village Foundation, and was placed on display on January 28, 1987. The last fixed-wing homebuilt to be found at Pioneer Village is a Rand Robinson KR-2, a small fiberglass and wood kit plane powered by a Volkswagen engine and designed with removable wings for easy storage and transportation. In contrast to some of the other airplanes at Pioneer Village, the KR-2 did have to venture far to arrive in the museum, for its builder and pilot, Michael Fitzsimmons, was from Minden, NE. The aircraft was donated by Fitzsimmons and is displayed with its wings and engine cowling removed.

Rotary-wing enthusiasts will also be satisfied with the Pioneer Village, which features a Sikorsky HNS-1, a variant of the R-4 flown by the US Coast Guard during WWII. The helicopter here at Pioneer Village originally built for the US Army Air Force as serial number 43-28229, but was transferred to the Coast Guard to become Bureau Number 39034, and be used for flight testing at NAS Patuxent River, MD and the National Advisory Committee of Aeronautics (NACA) laboratory at Langley Field, VA.

It was during this time that 39034 also became the first helicopter to survive being forced down due to a rainstorm. On March 18, 1944, HNS-1 39034 set off from Floyd Bennett Field/NAS Brooklyn, NY, bound for NAS Patuxent River, flown by Commander F.A. Erickson, who was accompanied by a passenger, Captain W.J. Kossler. On approach to a stopover in Baltimore, the helicopter encountered a drizzle that turned to light rain. Despite the fabric on the wooden blades being slightly frayed, they were not deemed to be too damaged to press on, and weather reports indicated improving conditions in Washington, D.C. Just twelve minutes later, though, Erickson and Kossler heard a loud report and Erickson felt a heavy vibration in the control stick. The helicopter was over a wooded area, but with a cloud ceiling of four to five thousand feet and visibility of between four to five miles, the men spotted a clear field one mile downwind from their position. They decided to land there approximately four miles from Fort Meade. One of the blades was discovered to have a 20-inch frayed section of fabric, and some light fraying on the other two main blades. A truck was sent to collect some replacement blades from Floyd Bennett Field, while an armed sentry was posted to the helicopter overnight. The next day the truck arrived, and the replacement blades allowed the HNS-1 to take off and fly to Fort Meade and wait out the weather. Two days later, on March 21, HNS-1 39034 arrived at Patuxent River without further incident. After WWII, the helicopter was sold for surplus, was registered with the FAA as N75378, and was later acquired by Harold Warp for display at Pioneer Village.

Suspended next to the Sikorsky sits an earlier form of rotorcraft in the form of a Pitcairn PAA-1/PA-24 autogiro, which was used by Paramount Air Service of New Jersey for aerial advertisements. Also on display are two aircraft developed by Igor Bensen; a B-6 rotary kite, and a B-7M autogiro, both intended to be kits for homebuilders. The B-6 at the Pioneer Village, which was intended to be towed into air by a car or boat, was purchased by Harold Warp from Robin Hermanson of Garnetson, SD, and the B-7M was built by Arnold Berg of Baltic, SD, from whom Warp purchased the B-7M from in 1973.

Though the airplanes and helicopters at Pioneer Village are far from the only thing to see, the aviation enthusiast will go home quite satisfied with the rarity and originality of the aircraft displayed at the museum. The rest of the collections, though outside the scope of this publication, are well-worth seeing as well, and the scale of the museum is truly something that has to be seen to be believed. Just as one thinks they have seen enough, one can walk into another of the multiple historic buildings to find much more than they could ask for! To learn more about the museum, visit the museum’s website HERE. The museum is open seven days a week, with the exception of Thanksgiving and Christmas, and in addition to day passes, the museum also sells a two-day pass for those interested in getting the full experience.

A truly amazing display of Americana! If you have time plan to spend the day or two. You can fly into the local airport and Pioneer Village has courtesy cars to drive to the museum.

Absolutely! This museum had been something I had been aware prior to my visit in July of this year while returning from Oshkosh but going there blew my expectations out of the water!