In the world of aviation, Howard Hughes is known for such films as Hell’s Angels and Jet Pilot, the H-4 Hercules flying boat (better known by its derisive nickname, the “Spruce Goose”), helicopters such as the OH-6 Cayuse, and spacecraft such as the Surveyor landers and the Magellan satellite. But before all that, Howard Hughes’ first venture into creating an aircraft of his own vision was the Hughes H-1 Racer, one of the sleekest planes of its day, with wide-reaching impacts on aerospace design.

After inheriting the fortune accumulated by his father through the Hughes Tool Company, which manufactured drill bits used in the oil industry, Howard Hughes relocated from Texas to California to pursue his two primary interests: filmmaking and aviation. He produced and directed what was then the most expensive film of the day, the World War I aviation epic Hell’s Angels. Hughes also gained experience with the fledgling airlines when he assumed an alias and flew for American Airways (now American Airlines) until his true identity was discovered. In January of 1934, Hughes competed in the All-American Air Meet held in Miami, Florida, and won the Sportsman Pilot Free for All while flying a highly modified and streamlined Boeing Model 100A (the civilian version of the P-12/F4B fighter). However, Hughes was never one to rest on his laurels, and as he surveyed the airplanes parked in Miami, he told his chief aeronautical engineer, Glenn Odekirk, “Hell, Glenn, there isn’t a decent plane in the lot.” Odekirk replied, “Howard, you’ll never be satisfied until you build your own.” With that, Hughes decided to commission the construction of what would become the world’s fastest land-based airplane.

To achieve this vision, Hughes would install Glenn Odekirk as project manager, and hire an engineer educated at the California Institute of Technology (CalTech) named Richard “Dick” Palmer to head the design team that was to be assembled for the newly founded Hughes Aircraft Company, which started as a division of the Hughes Tool Company. Palmer and his team created wooden models of various airfoils, engine cowlings, and tail surfaces in a rented garage before bringing them to Caltech in Pasadena, where they utilized the school’s wind tunnel to test the designs until they were satisfied with the results. Once Hughes saw the tests for himself, he rented space in a hangar from aircraft broker Charles Babb at the Grand Central Air Terminal in nearby Glendale.

The construction of the aircraft that came to be called the Racer would be kept a closely guarded secret. Hughes had a wooden wall built around the aircraft, screening it for all employees, and hired an armed guard for night watch. Yet word got out that Howard Hughes was building a new airplane, and the press dubbed it the “Hughes Mystery Ship”. Howard Hughes always referred to the aircraft as the Hughes 1B Special, but just as history would remember the H-4 Hercules flying boat as the Spruce Goose, the 1B Special is universally known as the Hughes H-1 Racer.

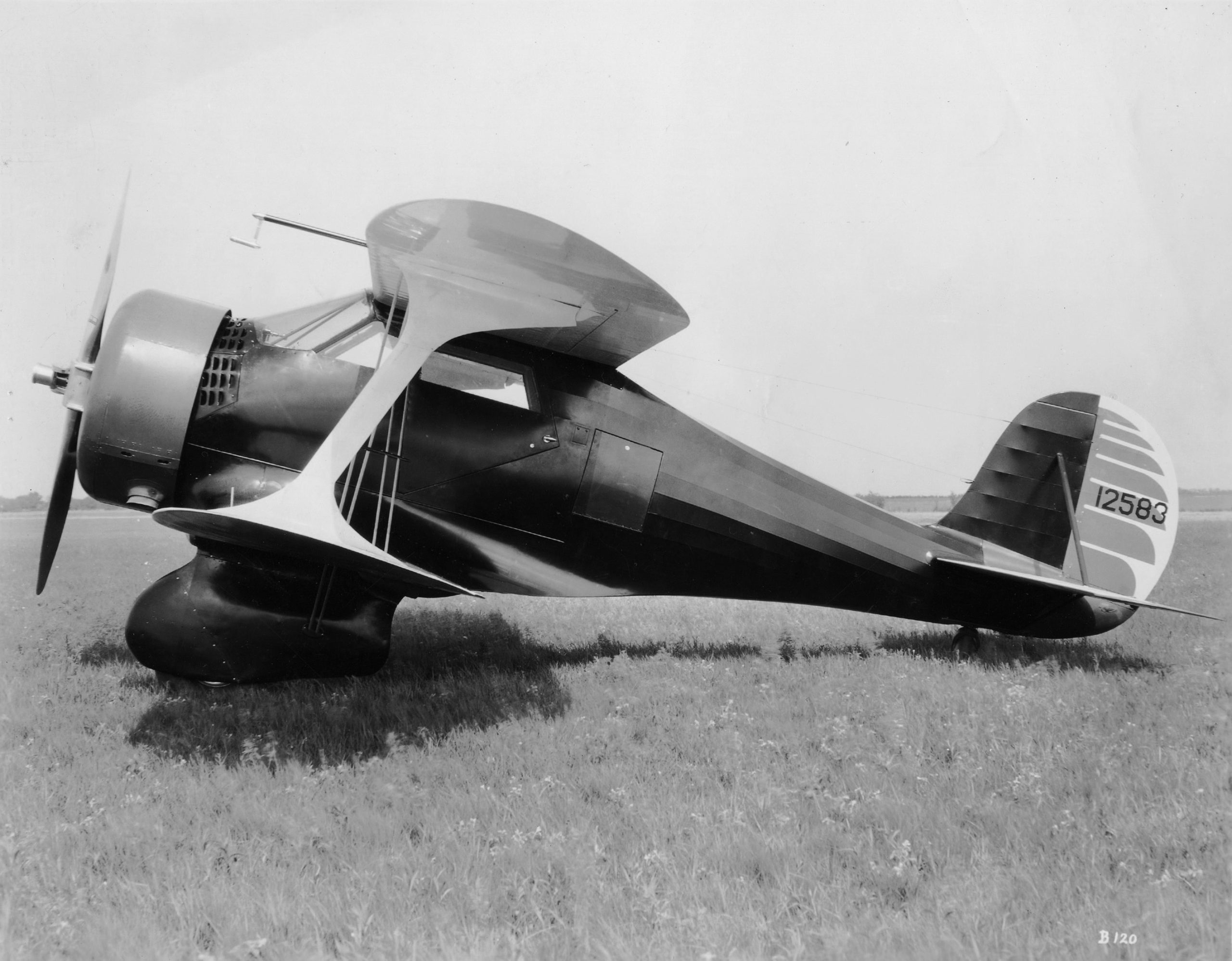

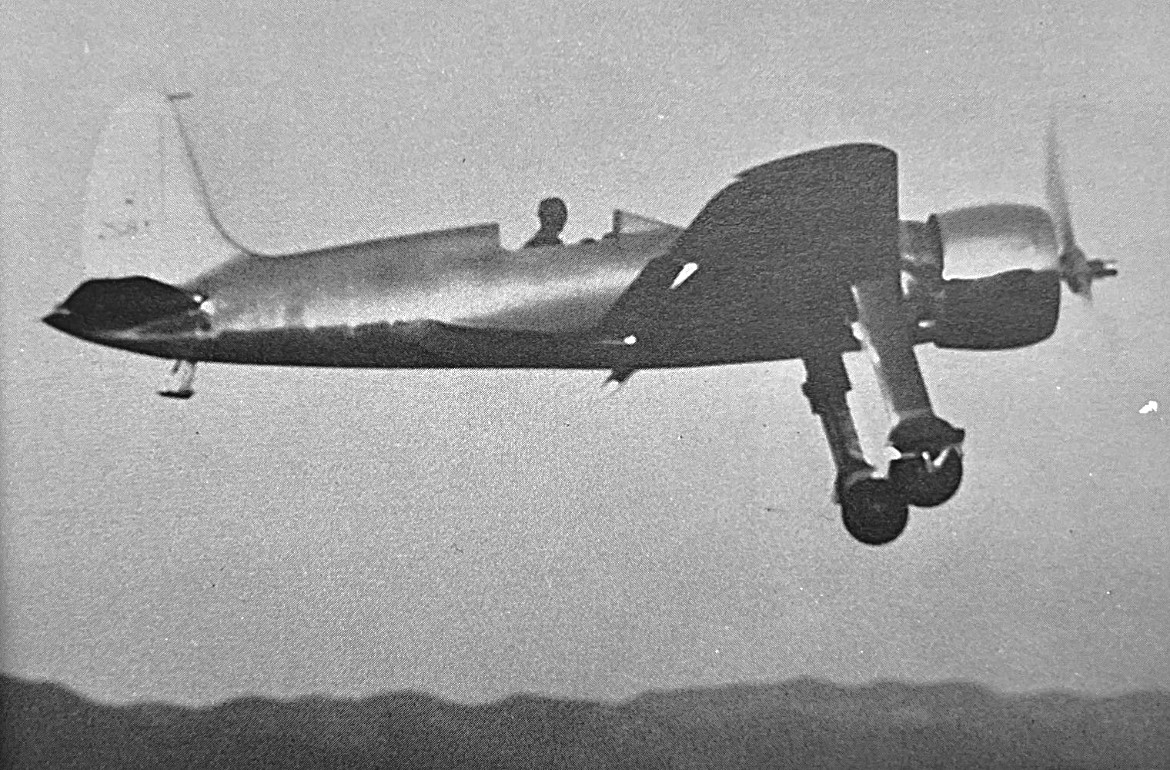

The aircraft featured a 27-foot-long aluminum fuselage, held in place by flush rivets, which gave the aircraft a clean, aerodynamic profile. While it was not the first airplane fitted with flush rivets, it certainly helped popularize the use of these streamlined rivets in the construction of future aircraft. The cockpit was enclosed, with an adjustable seat for Hughes to look over the long nose of the Racer on takeoff and landing. The H-1 was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1535 Twin Wasp Junior radial engine housed inside a bell-shaped streamlined cowling, and the wingspan measured 24 feet, 5 inches.

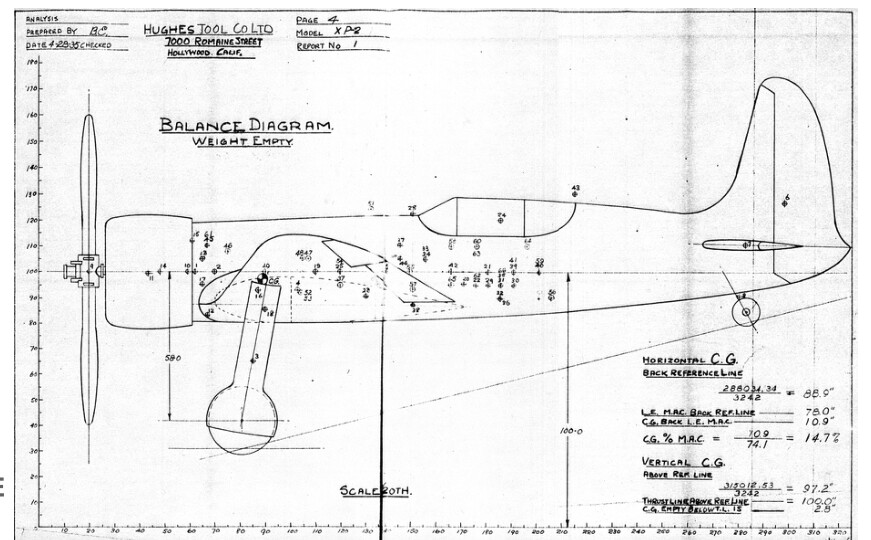

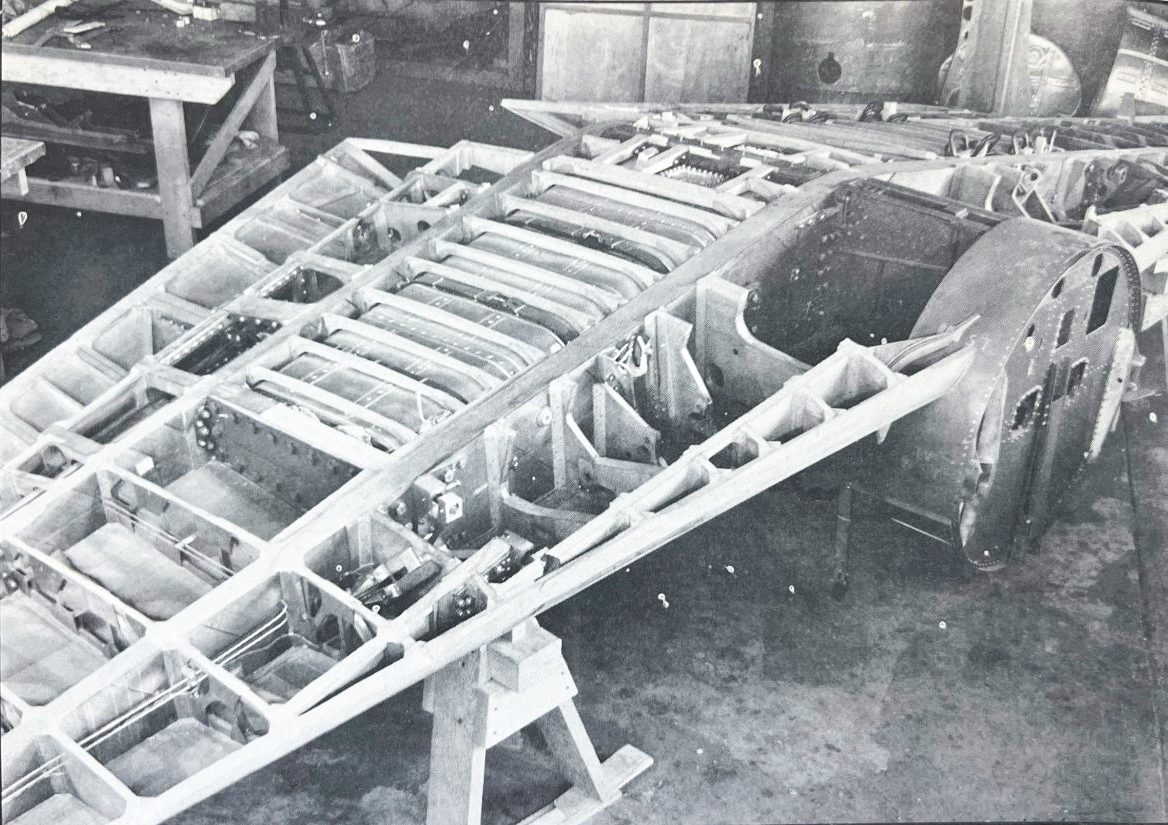

Unlike the fuselage, the wings were constructed from wood to save weight and get the best contours to reduce drag, which was achieved through meticulously shaping, sanding, and varnishing the airfoil of the wings. The aircraft was also fitted with wide-width retractable landing gear for improved ground handling, which contrasted with the narrow width of similar monoplane designs being introduced as fighter aircraft, such as the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and later the Supermarine Spitfire. At the same time, the Racer was taking shape at Grand Central Air Terminal, Hughes envisioned the 1B Special as becoming the U.S. Army Air Corps’ newest and fastest fighter. Designated the Hughes XP-2, the aircraft was to have a 30-foot wingspan, enlarged tail surfaces, a higher aspect ratio, and room in the wings for machine guns to be fitted.

The plans for the XP-2 were brought to Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, by Jesse Bennett ‘J.B.’ Alexander, one of Hughes’ flight instructors, in August 1935 to be entered into the Army Air Corps’ latest pursuit aircraft competition. It was also in this competition that the Wedell-Williams Air Service Corporation, known for their air racers such as the Model 44, made popular at the Bendix Trophy races, submitted their design, which they called the XP-34. Lastly, Alexander P. de Seversky submitted a design called the SEV-2X, a two-seater hastily converted into a single-seat fighter prototype.

Ultimately, the USAAC deemed none of the proposals acceptable. Still, as Seversky was the only one to have an actual aircraft built, they were allowed to work on a new prototype to submit in 1936, which then became the P-35 fighter, the Army Air Corps’ first operational pursuit aircraft with retractable landing gear and an enclosed cockpit. In the Army’s judgment, the Hughes Aircraft Company was a young upstart that had not yet built an airplane, let alone a proven design to demonstrate to the Army. Nevertheless, Hughes did not give up on his design for a fighter based on the H-1 Racer.

All the while, Hughes continued to rack up flying hours in several aircraft from single-engine landplanes to multi-engine flying boats. One such aircraft that he flew was a unique variant of the Beech Model 17 Staggerwing, the A17F, which was fitted with a 690 hp Pratt & Whitney R-1820, giving it a high landing speed for the time, similar to the speed Palmer predicted the Racer would have on landing. According to aviation historian Paul R. Matt, Hughes racked up 45 hours of flying time in the A17F Staggerwing between purchasing it on April 20, 1935, and before selling it off just three months later on July 29. He also entertained wealthy guests aboard his private yacht, the Southern Cross.

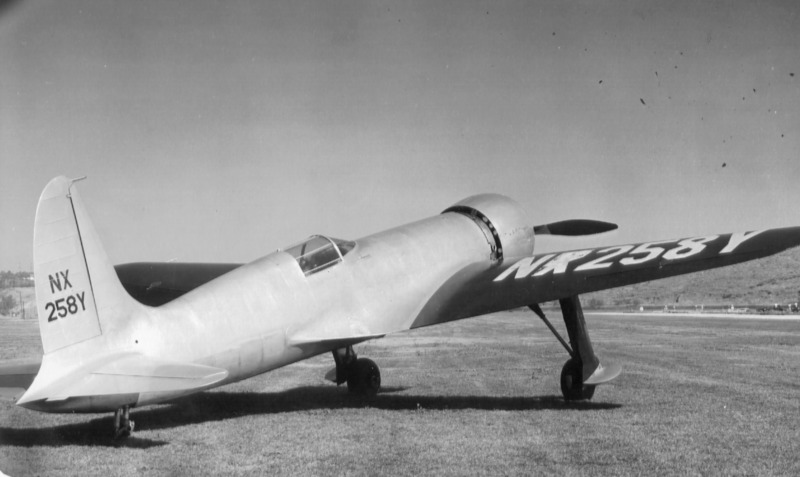

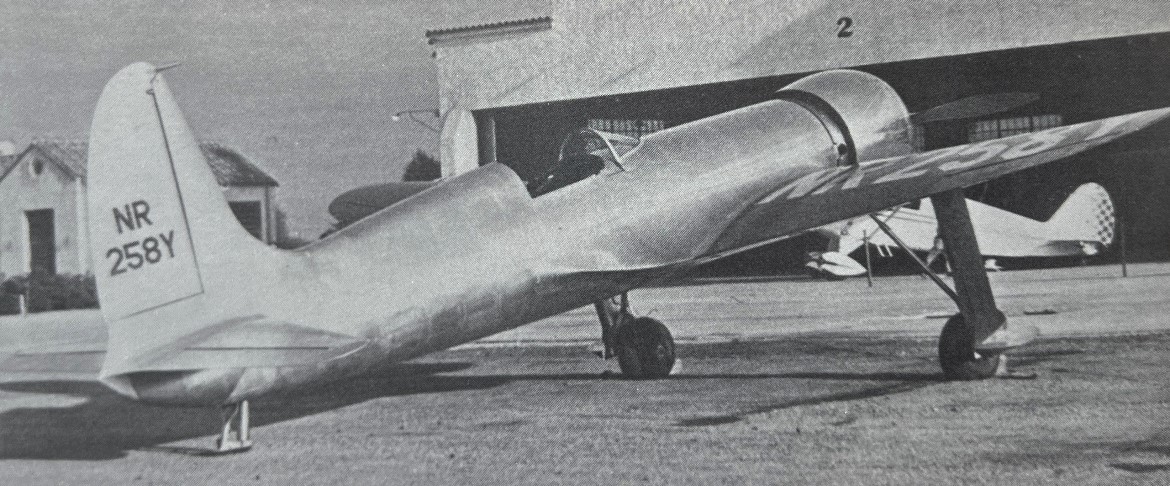

On August 10, 1935, the H-1 Racer, registered as NR258Y, was officially completed, just 16 months after initial design work began. Seven days later, on August 17, the Hughes 1B Special emerged from the shadows into the California sun, a gleaming, streamlined monoplane. It was then brought from Glendale on a flatbed truck to a much more spacious airfield in Los Angeles, Mines Field (now Los Angeles International Airport) for its maiden flight, with Howard Hughes himself at the controls, following his earlier practice flight that day in a Pitcairn autogiro. His entourage tried to convince him to let another pilot do the first flight. Still, Hughes enjoyed the thrill of flight too much, and after fitting into his flight overalls and climbing into the cockpit, the H-1’s Pratt & Whitney Wasp Junior engine roared to life. The aircraft sped down the runway and into the overcast skies above Los Angeles.

As Hughes climbed to altitude, he realized that complications with the constant-speed propeller prevented him from going faster than 250 mph. Hughes decided to cut the first flight short and landed back at Mines Field just 15 minutes after taking off. The next day, Glenn Odekirk, Hughes engineer Jim Petty, and Pratt & Whitney’s West Coast representative Bill Gwinn inspected the propeller governor and discovered that the bevel gears had not come together properly and had chewed each other up. Consequently, new parts were ordered from Hamilton-Standard in Connecticut and flown to California to be promptly installed on what the plane’s Howard called the Hughes 1B Special, which would be the aircraft’s official designation with the federal aviation authorities.

Ten days later, on August 28, it took off on the 1B/H-1’s second flight. Hughes flew out over the Pacific coast for an hour before turning north to land at Union Air Terminal in Burbank (now Hollywood-Burbank Airport). Yet Hughes was not free from trouble on this flight either. As he approached the Union Air Terminal, the main landing gear failed to extend on approach. Hughes tried every trick he knew to throw the gear open, twisting and jerking the aircraft, but nothing worked. Just when he considered bailing out, nearly jamming the aircraft’s canopy in the half-open position, Hughes tried one last feature, an emergency valve back-up system designed by Odekirk that would allow engine oil to be used in the hydraulic system to force the gear down in an emergency. Hughes had initially felt that this was unnecessary, and it led to a heated argument between him and Odekirk, who barely managed to convince Hughes to give the valve system a chance. Odekirk would prove to be correct, as the gear slowly came down from the landing gear wells. With the gear locked, Hughes landed at Burbank after 1 hour, 15 minutes in the air.

A subsequent inspection revealed that the cause of the landing gear failure was that the cover on the main hydraulic pump had blown its head gasket. With the installation of a newly designed gasket, the Hughes 1B Special/H-1 Racer was ready to fly again. With the hydraulic problems situated, Hughes began preparing to break the world’s landplane speed record. At the time, land-based aircraft were only beginning to catch up in speed to the swift and elegant seaplane racers built for the Schneider Trophy races that had concluded in 1931 with Britain’s final victory in the Supermarine S.6B, the first aircraft to exceed 400mph. By the summer of 1935, the current landplane speed record had stood for less than a year after French pilot Raymond Delmotte achieved an average speed of 505.85 kilometers per hour (314.32 miles per hour) in a Caudron C.460 Rafale racer on Christmas Day, 1934, at Istres, France.

Hughes was confident that the aircraft could beat the Frenchman’s record, and Hughes made two more flights in the H-1 around Burbank on September 9 and 11, and with just over 3 hours of flight time on the airframe, Hughes would bring the Racer to Eddie Martin Airfield, a small flying field established in 1923 by its namesake pioneer aviator in Santa Ana. Long since redeveloped, the land sits one mile north of present-day John Wayne Airport.

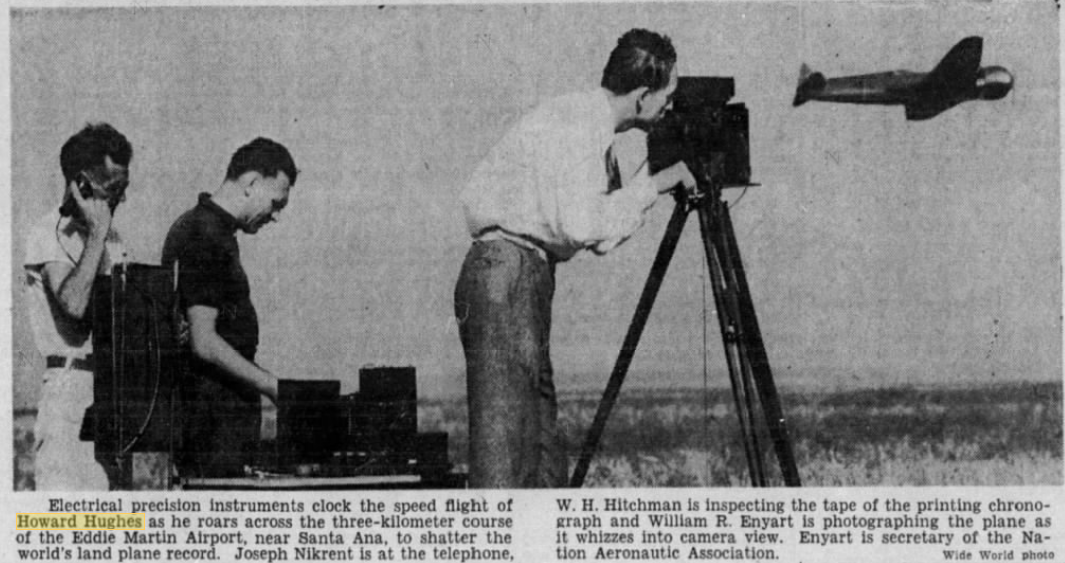

The official recorder was William R. Enyart of the National Aeronautic Association, the United States’ representative for the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI). Assisting him were William Curtis Rockefeller, W.M. Kenmore, and R.C. Talbott. Other observers for the NAA/FAI included Larry Therkelsen. Others associated with Hughes came to watch the attempt, such as Racer designer Dick Palmer, pilot Carl Lienesch, engineer Carlos Wood, Jim Petty, and Hughes’ executive assistant, Noah Dietrich, among others.

To ensure that Hughes stuck to the prescribed altitude, two pilots would fly above Hughes. These two were none other than Amelia Earhart and movie pilot Paul Mantz. Nine months earlier, Earhart made history by becoming the first pilot to fly solo from Hawaii to California in a new Lockheed Vega 5C, NR965Y, and Mantz had gone to Hawaii to help prepare Earhart for that flight. Now they would fly together as the two official aerial observers for Hughes’ record-setting flight.

The rules for the flight would be that Hughes would make four passes (two upwind, two downwind) flying between an array of electric-eye photo timers set up at the ends of the 3-kilometer course adjacent to Eddie Martin Field. Hughes was to fly no higher than 300 meters (approximately 1,000 feet) outside the course and maintain an altitude of 60 meters (200 feet) while flying the course. The aircraft also had to land without any serious incident, which would have disqualified any attempt.

Everyone except Hughes was to make his attempt on the record on September 12. Yet when Hughes first flew from Burbank to Santa Ana, it was in a rented Waco Cabin biplane. For nearly an hour and a half, Hughes went through practice runs over the 3-kilometer course, taking mental notes on the local landmarks, terrain, and weather, all factors that could impact the actual speed runs in NR258Y.

Soon, Hughes returned to Burbank to swap the Waco for the 1B Special and took off for Martin Field. When Hughes finally landed the H-1 at Eddie Martin Field, evening was already approaching, and the officials grumbled at having to wait so long. Hughes dismissed these murmurs, though, and soon got the 1B fired up and was in the air to begin breaking Delmotte’s record. Hughes made the four runs, but just as he was barreling in for a fifth pass, the judges signaled him to land because the evening light was no longer sufficient for the photocells to record the passes. They would have to wait until the next day for Hughes to make a new attempt.

September 13, 1935: After a sleepless night of tinkering on the Racer, Howard Hughes was ready to make another attempt at the world speed record. The superstitious may have objected to making an attempt on a speed record on Friday the 13th, but Hughes was not among those people. A day for flying was a day for flying. Amelia Earhart and Paul Mantz went up in the red Lockheed Vega and circled the field while the blue wings and silver fuselage of the Hughes H-1 Racer glistened as the roar of its Pratt & Whitney radial engine could be heard in the beet fields below.

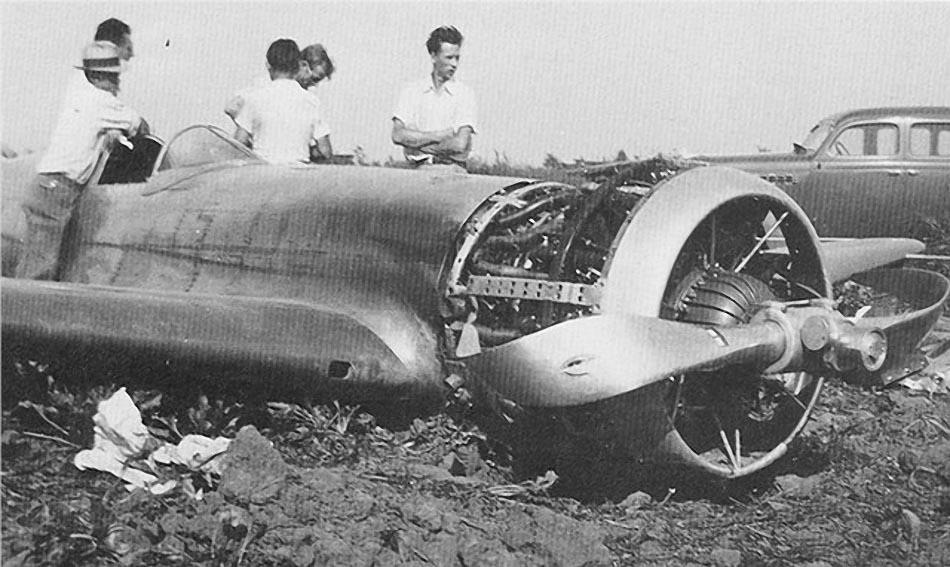

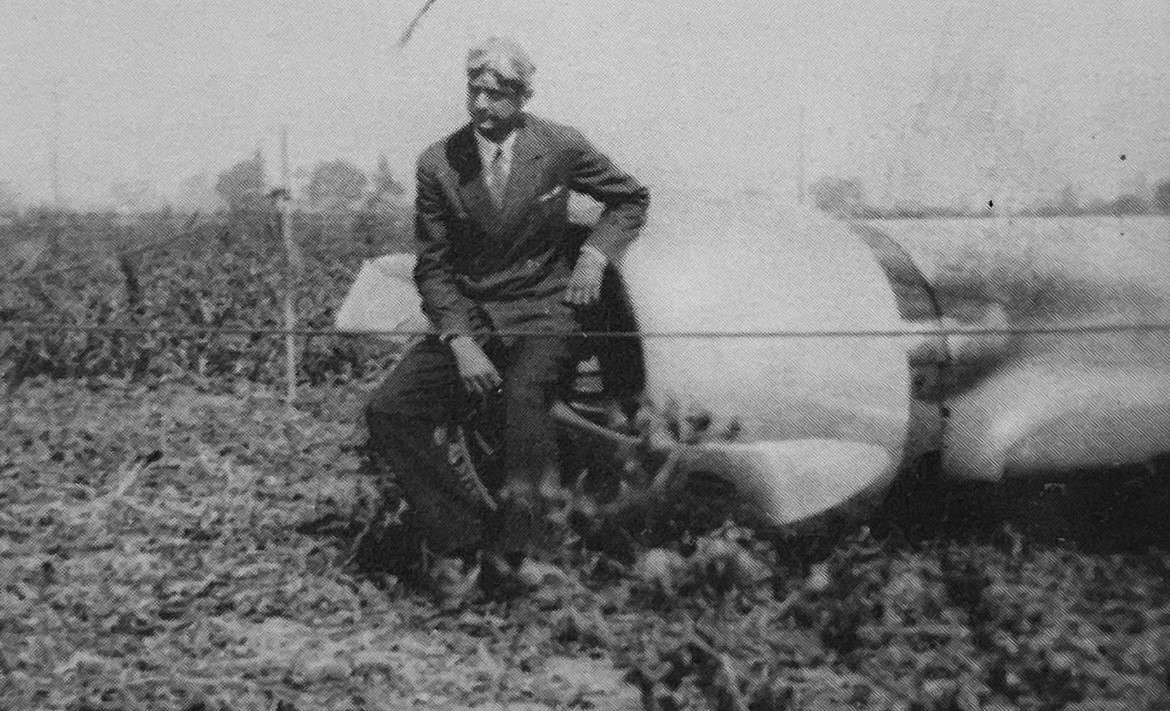

Hughes made his first pass, then his second, then his third, then his fourth, the silver bullet appearing as a blur to the official observers and timers. With a wingspan of just 24 feet, 5 inches, Hughes dared not make any sharp turns, extending his upwind turns as far as the Balboa Pier on Newport Beach before making another straight-line pass. However, Hughes was not satisfied with just four passes, and the H-1 thundered in for a fifth and a sixth pass. But then, as he began climbing to make a seventh pass, an eerie silence came over the fields outside Santa Ana. In the cockpit, Hughes realized he had exhausted the fuel supply in his main tank. Though he still had an auxiliary tank, Hughes figured he was too low for the engine to restart, but with the momentum he had built up, he gained what altitude he could, turned into the wind, and assumed a glide approach in the direction of Eddie Martin Field. Keeping the nose as high as he could without stalling the H-1, he made a belly landing in a nearby beet field.

Seeing the dust from the belly landing, Hughes’ entourage and the NAA officials raced to the scene in their cars and trucks, fearing the worst. When the first would-be rescuers arrived on the scene, the dust had yet to settle, but the 29-year-old millionaire pilot was calmly writing notes into his logbook while sitting on the airplane. He looked at them and asked with a smile, “Did I make it?” Having landed with Amelia Earhart, Paul Mantz was quoted as replying, “Howard, you broke the record, and you are the luckiest son of a bitch I ever saw!” It would be two months before the FAI would certify the results, but the preliminary results indicated that Howard Hughes had broken Raymond Delmotte’s record by a considerable margin. All the NAA/FAI officials had agreed that, given the controlled nature of the belly landing and the minimum damage the Hughes 1B Special sustained, the record would remain official. On November 5, 1935, the FAI headquarters in Paris would certify that Hughes had flown at an average speed of 352.388 mph (567.155 kph). Meanwhile, Hughes would call Glenn Odekirk to send a flatbed truck to retrieve the Hughes H-1 Racer and drive it back to Burbank for repairs.

Although German WWI ace and Luftwaffe general Ernst Udet would exceed this speed record on June 5, 1938, flying a prototype of the Heinkel He 100 fighter to an average speed of 634.73 km/h (394.40 mph) over Rechlin, Germany, Hughes’ world speed record would officially stand for four years until German test pilot Hans Dieterle officially broke the record on March 30, 1939, while flying another He 100 prototype at Oranienberg, Germany 746.60 kilometers per hour (463.91 miles per hour). Less than one month later, though, another German pilot, Fritz Wendel, flew the Messerschmitt Me 209 racer to a blazing 755.14 kilometers per hour (469.22 miles per hour) on April 26, 1939, a record that would stand for piston-engine aircraft for 30 years.

As soon as the FAI verified the 3-kilometer speed record, Howard Hughes wanted to modify the aircraft to set a new transcontinental speed record, flying nonstop from coast to coast. Palmer was certain that such a feat meant that the plan would have to have a new set of wings to carry the fuel for the flight. Hughes told Palmer, “It’s a beautiful airplane, Dick. I can’t see why we can’t use it all the way.” With that, Glenn Odekirk and Richard Palmer would get to work on leading the Hughes team to build a new wing for the Racer to prepare it for the transcontinental flight.

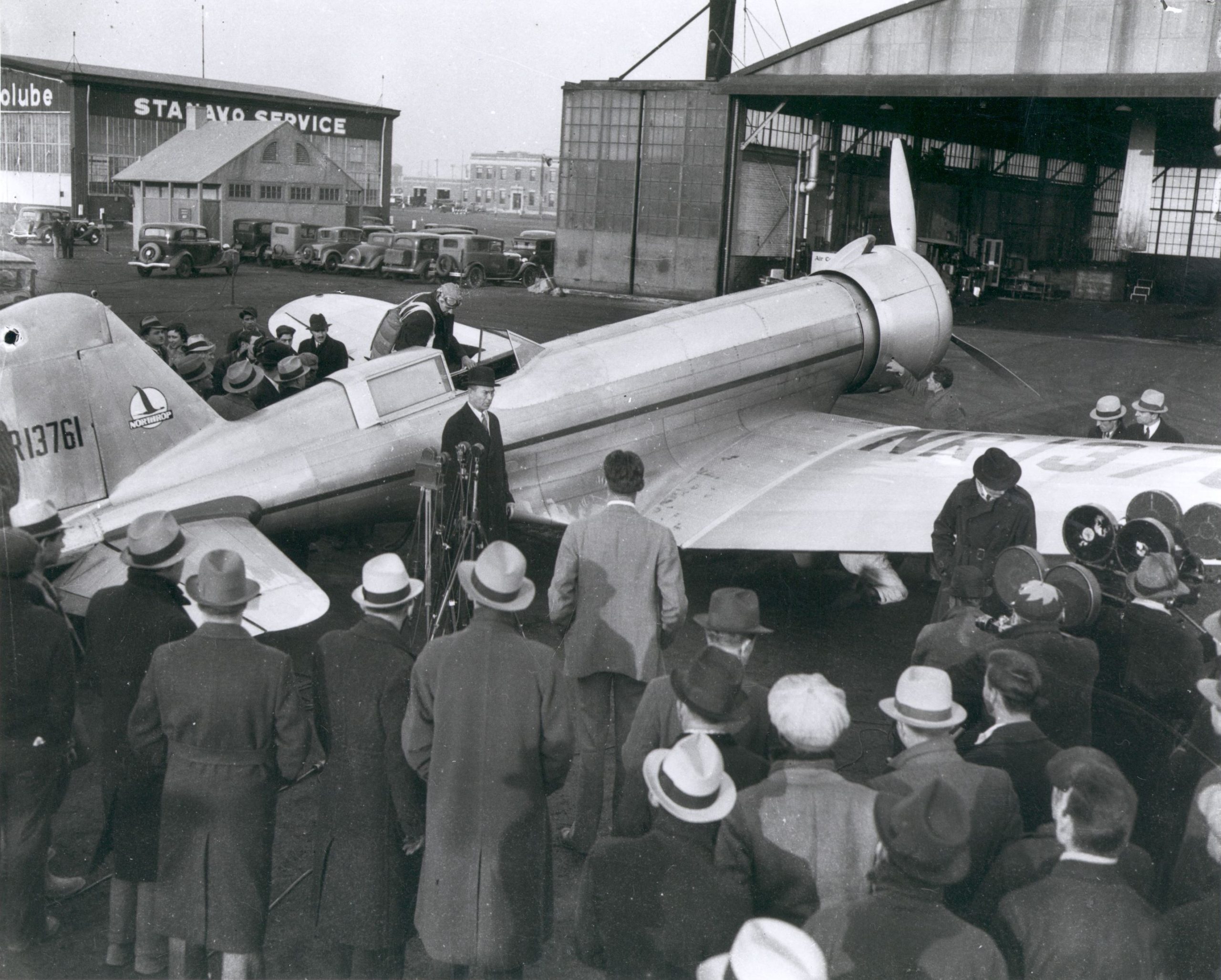

With the Hughes H-1 Racer being repaired at Union Air Terminal in Burbank, Howard Hughes managed to get Jacqueline Cochran to lease him her Northrop Gamma 2G, NC13761, which she had initially sought to fly in both the 1934 MacRobertson Air Race and the 1935 Bendix Race but was unable to complete either. Hughes had the Gamma modified with a Wright R-1820 Cyclone in place of the Pratt & Whitney R-1535 Twin Wasp Junior Cochran had installed. At 12:15 pm on January 13, 1936, Hughes took off in Cochran’s Gamma from Burbank’s Union Air Terminal, aiming to land in Newark, New Jersey, to set a transcontinental record. Just after midnight on January 14, Hughes touched down at Newark at 12:41 am, setting a new transcontinental record of 9 hours, 26 minutes, 10 seconds, at an average speed of 417.0 kilometers per hour (259.1 miles per hour), at average altitudes between 15,000 to 18,000 feet while on supplemental oxygen in the unpressurized cabin. With the Racer being a smaller, more streamlined aircraft than the Gamma, which had fairings mounted over its fixed landing gear, Hughes was determined to break his own transcontinental record as soon as the H-1 had been rebuilt.

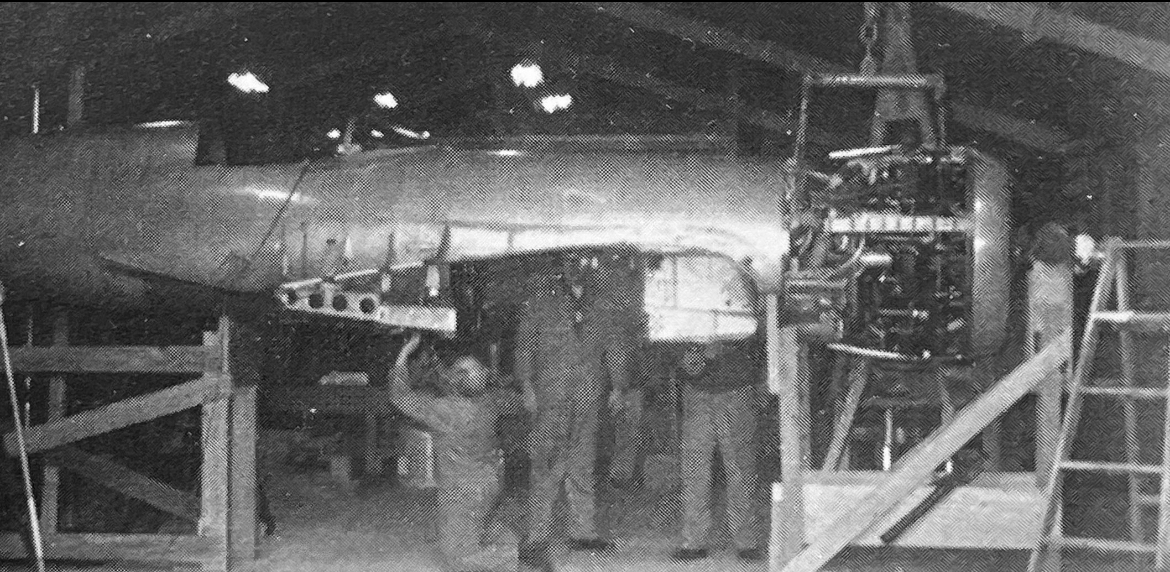

This time, the aircraft would be fitted with a new wing, measuring 31 feet, 9 inches in span, and featuring a new airfoil. The main difference is that the new “long-wing” model would feature larger fuel tanks mounted between the two wing spars to increase the Racer’s range. The H-1 would also be fitted with a hydraulic-operated landing gear, mechanical linkages for the tail skid and flaps, an increase in the surface area of the elevators, a revised tail cone, navigational instruments in the cockpit, a radio, and an oxygen system. Lastly, the 700 hp Pratt & Whitney R-1535 was finely tuned to deliver between 850 and 900 hp for the long haul and nearly 1,000 hp for takeoff power and short bursts. Remarkably, the team led by Glenn Odekirk and Dick Palmer managed to incorporate all these upgrades at just 700 pounds above the original gross weight.

In the meantime, though, Hughes once again pursued other business and personal ventures and returned the Northrop Gamma to Jacqueline Cochran. Throughout 1936, the Hughes H-1 Racer received numerous upgrades during the rebuild. The instrument panel and cockpit were fitted with navigational equipment, a radio, and an oxygen system. Occasionally, Hughes would check on the progress of the H-1, then went off to continue flying an increasing number of aircraft that he both owned outright or leased for temporary use. On December 28, 1936, Hughes took the newly modified H-1 Racer up for its first flight since the record set in Santa Ana. After a 20-minute flight, Hughes returned to Burbank, filled the tanks to their full capacity, and flew for another 2 hours and 15 minutes.

On the evening of January 18, 1937, Hughes had Glenn Odekirk and Jim Petty fill the H-1’s tanks and would take off from Burbank for another round of test flights to check the airplane’s fuel consumption rate. During the flight, Hughes made a series of speed runs at various altitudes between the Santa Monica Pier and Union Air Terminal, testing the aircraft’s straight run mileage against prevailing winds. After an hour and 25 minutes, Hughes landed back at Burbank and had the tanks filled up again. Then, Hughes and Odekirk began making calculations on some notepaper on the wing of the airplane. After both men had come to the same solutions, Hughes declared, “Hell, I can make New York at that rate. Check her over and make the arrangements. I’m leaving tonight.”

In the predawn hours of January 19, 1937, Hughes took off from Burbank’s Union Air Terminal in the H-1 Racer at 2:14 am PST. On the ground, NAA/FAI representative Joe Nikrant clocked the official departure time and watched as the H-1 disappeared into the night and the roaring sound of its tuned-up Wasp Jr. radial engine dissipated into silence. Settling between 14,000 and 18,000 feet, Hughes followed the path he took with the Gamma he borrowed from Jackie Cochran, and once more donned his oxygen mask as he maintained a northeastern heading. During the flight, Hughes kept the radio off, preferring the metallic symphony of the Racer’s Pratt & Whitney to the radio chatter of morning flights. Around midday he appeared in the skies over Newark Airport but was forced to wait in a holding pattern for a United Air Lines Douglas DC-3 to take off.

Nevertheless, NAA timer Bill Zint recorded Hughes and the H-1 landing at Newark Airport at 12:42:25pm EST. Hughes had spanned the North American continent in 7 hours, 28 minutes, and 25 seconds, breaking his own record in Cochran’s Northrop Gamma by more than two hours, having flown at an average speed of 327.1 mph. His transcontinental speed record would stand for ten years before Paul Mantz broke the record in a modified P-51C Mustang “Blaze of Noon” (later flown nonstop from Norway to Alaska by Charles Blair Jr. as “Excalibur III”) on February 28, 1947.

Though it was occasionally run up, Hughes did not fly the racer, as he became obsessed with planning to break round-the-world speed record, which eventually resulted in Hughes setting a new world record with co-pilot and navigator Harry P. McLean Connor, 1st Lieutenant Thomas Lawson Thurlow of the United States Army Air Corps as second navigator, radio operator and National Broadcasting Company (NBC) field engineer Richard R. Stoddart, and flight engineer Edward Lund in a Lockheed Model 14 Super Electra, NX18973, flying from Floyd Bennett Field, Brooklyn, NY with stops at Paris-Le Bourget, Moscow, Omsk, Yakutsk, Fairbanks, Minneapolis, and back to Floyd Bennett in 91 hours, 14 minutes, 10 seconds, leading to the reserved Hughes receiving a ticker-tape parade in Manhattan, and earning the Collier Trophy.

Meanwhile, the Army Air Corps had finally gained interest in the fighter variant of the Hughes H-1 Racer, and indeed, a revamped military design for the aircraft was drawn up. The design was primarily based on the transcontinental configuration of the plane, with the cockpit to be moved forward and to feature a larger canopy. Perhaps the most significant difference between the original design and the second military design was that the latter was to be powered by the Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial engine. However, this design would never leave the drawing board. Eventually, Hughes dropped this design in favor of a twin-engine, twin-boom aircraft that became the Hughes D-2, and then the Hughes XF-11 photo-reconnaissance prototype, neither of which was adopted for operational service.

In 1938, Richard Palmer took the opportunity to go his own way. On January 29, 1938, aircraft designer and chief engineer of the AVCO Aviation Manufacturing Corporation, Gerald “Jerry” Vultee, was killed alongside his wife, Sylvia Parker, when their Stinson Reliant crashed in a snowstorm near Sedona, Arizona. Having worked under Vultee and other designers such as Lockheed before being hired by Hughes, Palmer was invited to take Vultee’s place as chief engineer of what would become the Vultee Aircraft Company. Upon informing Hughes of his decision, Hughes tried to persuade Palmer to remain under his employ, but Palmer decided to stick with his decision and moved on to Vultee. The two men never spoke to each other in person again, but Richard Palmer would have success overseeing the design of aircraft such as the Vultee P-66 Vanguard fighter, the A-35 Vengeance attack bomber, and, most famously, the Vultee BT-13 Valiant basic trainer, which helped train thousands of Allied airmen during WWII.

Perhaps the least discussed aspect of the Hughes H-1 Racer’s story is its status during World War II. In 1940, Howard Hughes sold the H-1 Racer and the accompanying plans to modify the aircraft into an Army pursuit plane to the Timm Aircraft Company of Van Nuys, CA, for $110,000 (over $2.5 million in 2025). The small aircraft manufacturing company was led by brothers Otto and Wally Timm, the former of whom had been the flight instructor for none other than Charles Lindbergh. However, there were some strings attached to this purchase, as Hughes bought back an equal sum of $110,000 worth of stocks in the company, becoming the Timm Aircraft Company’s largest shareholder, and thus continued to hold sway over what became of the Hughes Racer.

Soon, Otto Timm and another test pilot/aeronautical engineer, Vance Bresse, began flight testing the H-1 Racer over Los Angeles in 1940 under the registration NX258Y, with aviation historian Paul Matt reporting that Timm referred to the aircraft as the Model T or the “Gadfly”. While both Bresse and Timm had ideas for where the Hughes H-1 Racer could be modified into a fighter, the development of other aircraft had moved well past the five-year-old racer, with Bresse himself becoming the first pilot to fly the North American NA-73X, the prototype for what became the P-51 Mustang.

Around the same time Otto Timm and Vance Bresse were flying the Hughes H-1 Racer around the San Fernando Valley, Howard Hughes purchased an initial 380 acres in the Balboa Wetlands in a southwest area of Culver City and developed an aircraft production plant and a runway just 1-2 miles north of current day Los Angeles International Airport. This was to become Hughes Airport, where the Hughes Aircraft Company would relocate its headquarters from Burbank, and which became the birthplace to such aircraft as the Hughes D-2 attack aircraft prototype, XF-11 photo-reconnaissance aircraft (which nearly killed Hughes in a catastrophic 1946 accident in Beverly Hills), and the gargantuan flying boat the H-4 Hercules (better known to history as the Spruce Goose), which would migrate in pieces to the Port of Los Angeles for its one and only flight in 1947.

With the development of Hughes Airport, Howard Hughes purchased the H-1 Racer back from the Timm Aircraft Company, along with his share of stocks in the company, in exchange for $10,000. The Timm Aircraft Company saw some modest success during WWII, though, building the Timm N2T Tutor training aircraft for the US Navy and acquiring a production license to build Waco CG-4 combat gliders for the Army Air Forces.

Meanwhile, the Hughes H-1 Racer, which Hughes still called the Hughes 1B Special, was moved back into the shadows, this time to Hangar 24, a climate-controlled hangar at the Hughes Airport. The aircraft was kept in a corner of the hangar, covered in tailor-made cotton sheets and surrounded inside the hangar by a chain-link fence. Every month for over 30 years, Hughes employees poured hot oil through the engine and pulled the propeller. Yet the aircraft would never fly again after coming to Culver City.

Eventually, Hughes Aircraft transitioned into making helicopters, missiles, and satellites, with Howard Hughes becoming a recluse, and subject in the press to wild rumors regarding his current condition and his whereabouts. Yet whether he was in one of his various hotel penthouse suites from Las Vegas to Acapulco, he was still involved in managing his business empires, and some 30 years later, in the ultimate disposition of his famous racer.

By 1975, the H-1 Racer had been hidden from prying eyes at Hughes Airport in Culver City when negotiations between Hughes Helicopters and the Smithsonian Institution, which was finally constructing a permanent, dedicated building for the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., at last came to fruition. At last, after 30 years in the dark, 30 years a whisper among aviation enthusiasts, the Hughes H-1 Racer would enter the spotlight once again and reside in the nation’s aviation shrine. But unlike 1937, it could not simply fly nonstop across the North American continent again.

Originally, the Hughes company planned to ship the airplane intact on a cargo ship that would transit the Panama Canal and land on the East Coast. But when it became evident that the Hughes H-1 Racer had to be disassembled to enter the museum building before being reassembled inside the museum’s gallery spaces, Howard Hughes himself made a call from his latest penthouse, telling how the aircraft should be dismantled and put back together. Furthermore, Hughes insisted on refurbishing the aircraft to appear as it did when he landed it at Newark Airport following his transcontinental record set back in 1937.

This was done according to Hughes’ wishes, and among those who were there to supervise the disassembly and see the aircraft off were none other than Glenn Odekirk and Richard Palmer, now longtime veterans of the aerospace industry. The aircraft was refurbished at Hughes Airport, then transported to the National Air and Space Museum’s Silver Hill Facility (now the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility) in Suitland, Maryland, where underwent a final inspection before it was made ready to enter the halls of the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C.

However, the reclusive Howard Hughes would never see his Racer on public display. On April 4, 1976, after years of isolation from all but a few attendants, Hughes’ health had declined drastically through neglect, enough to warrant an emergency flight on a Learjet from his Mexican penthouse in the Acapulco Princess Hotel to Houston Methodist Hospital. Hughes never lived to see the hospital, dying aboard Learjet 24B N855W while still in flight. Three months later, the National Air and Space Museum, complete with the Hughes H-1 Racer, was officially opened at the height of the nation’s Bicentennial celebrations.

Over the next forty-three years, the Hughes H-1 Racer remained on display on the National Mall, while the short pair of wings the Racer wore on its speed run that ended in a California beet field, which Hughes had kept for all these years, were placed in storage at the museum’s Silver Hill Facility in Suitland. The museum changed a few of the galleries the Racer was in, but the one that most visitors would recall seeing on display in was the museum’s Golden Age of Flight gallery, where it sat alongside polar explorer Lincoln Ellsworth’s Northrop Gamma Polar Star, Steve Wittman’s Wittman Special 20 Buster midget racer, the Curtiss Robin Ole Miss flown by brothers Fred and Al Key on their 1935 flight endurance record, and a Beech Staggerwing once owned by Edwin E. Aldrin Jr., father of future Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin.

In recent years, though, the H-1 has been moved out of storage and on display in the Udvar-Hazy Center’s Boeing Aviation Hangar, albeit sitting disassembled with the fuselage and the wings in separate jigs under the tail of the Boeing 367-80, the prototype for both the Boeing 707 and the KC-135 Stratotanker. Curators at the National Air and Space Museum such as Robert van der Linden state that the museum is planning to reassemble the H-1 and have it on display in one piece, but with the final stages of the renovations in downtown Washington, no definitive date for when the aircraft will be fully reassembled has yet been established.

In the years since the original Hughes H-1 Racer was put in the Smithsonian, several replicas have been constructed. The first of which was a full-scale model displayed in the geodesic dome built to accommodate the “Spruce Goose” in Long Beach Harbor, CA, alongside the retired British ocean liner the RMS Queen Mary. When the Spruce Goose was relocated to the Evergreen Aviation and Space Museum in McMinnville, Oregon, the replica was later displayed in Reno, Nevada, at the short-lived National Air Race Museum, but was subsequently placed into storage. Another replica, built for use in the 2004 Howard Hughes biopic The Aviator, is on static display at the Santa Maria Museum of Flight in Santa Maria, California, alongside a cockpit section constructed for close-up scenes against a green screen, featuring actor Leonardo DiCaprio as Howard Hughes. Meanwhile, the San Diego Air and Space Museum is constructing a complete reproduction intended to go on display in the museum upon completion.

But perhaps the most accurate reproduction was the one in which pilot Jim Wright of Cottage Grove, Oregon, built an exact reproduction of the H-1 in its long-wing configuration, based on measurements taken of the original aircraft in the Smithsonian. With a passionate team behind him that put 35,000 man-hours into the project, Jim Wright’s H-1 flew in 2002 and was considered so accurate that it was often listed as the second H-1 racer built. After demonstrating the aircraft at the 2002 Reno Air Races, he flew it to the 2003 EAA Airventure airshow at Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Still, he was tragically lost in an airplane crash at Yellowstone National Park on his way back home from Oshkosh. While much more can and has been said of the triumph and tragedy in the story of Jim Wright, his story is worthy of its own dedicated article.