At the southern portion of San Diego’s Balboa Park and standing under the flight path of San Diego International Airport lies the San Diego Air and Space Museum. Situated in the historic Ford Building, constructed for the 1935 California Pacific International Exposition, the SDASM is visited by millions of visitors every year and is one of the premier aerospace museums on the West Coast of the United States. Yet most visitors are unaware that underneath their feet is a restoration workshop, where a full-scale reproduction of one of the most advanced aircraft of the 1930s is under construction by a team of volunteers. It is a reproduction of Howard Hughes’ H-1 Racer.

The original H-1 was constructed in 1935 with the financing of Howard Hughes Jr, who had developed a love of aviation, and had directed and produced the largest aviation movie of its time, Hell’s Angels. Hughes also won the Sportsman Pilot Free for All race in a highly modified Boeing Model 100A (the civilian version of the P-12/F4B biplane fighter) during the 1934 All-American Air Meet in Miami, Florida. However, Hughes sought to develop a new aircraft to go fast enough to break the world speed record for landplanes.

Hughes had two engineers under his employ, Glenn Odekirk and Richard “Dick” Palmer, draw up designs for such an aircraft, with Palmer and a select team of designers and engineers building wind tunnel models for testing at Palmer’s alma mater, the California Institute of Technology (CalTech) in Pasadena, California. After this preliminary work was finished, Hughes rented a warehouse from aircraft broker Charles Babb adjacent to the Grand Central Airport in Glendale, and had a team of engineers and builders construct the H-1 Racer (which Hughes always called the 1B Special). On August 17, 1935, the H-1 was brought from Glendale to Mines Field (now Los Angeles International Airport) where Howard Hughes took the aircraft for its first flight.

The Hughes H-1 Racer was a revolutionary aircraft for its time, from the counter-sunk flush rivets of its aluminum fuselage to the retractable landing gear that featured a wide track design seen in several fighters of WWII. The H-1 was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1535 Twin Wasp Junior 14-cylinder, twin-row radial engine, with a length of 27 feet and an original wingspan of 25 feet. Though the fuselage was made of aluminum, the wings of the H-1 were made of wood, sanded, contoured and varnished to obtain the smoothest surface of any wing area possible at that time. It was without dispute one of the sleekest designs of the 1930s.

After three more flights on August 28, September 9, and September 11, Hughes decided to set the world speed record in the H-1. A closed 3 Kilometer course was set up at Eddie Martin Airport, Santa Ana, California, near the current site of John Wayne Airport. Among the observers on the ground were members of the National Aeronautical Association (NAA), a member of the world governing body of air sports, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), while pilots Amelia Earhart and Paul Mantz flew above to ensure that Hughes did not exceed the set altitude restriction for his high-speed passes. On September 13, 1935, Hughes broke the world record by clocking in at 352.39 mph (567.12 km/h). In the attempt to guarantee his record, however, Hughes exhausted his limited fuel supply and was forced to land wheels-up in a nearby beet field. Yet Hughes was unharmed and unphased by the situation, the record still held, and the aircraft received only minor damage and was returned to Glendale for repairs.

On January 14, 1936, Howard Hughes set a new transcontinental speed record in a Northrop Gamma borrowed from Jacqueline Cochran, flying from Burbank, California to Newark, New Jersey in 9 hours, 26 minutes, 10 seconds, at an average speed of 259.1 miles per hour (417.0 kilometers per hour), and at an average altitude of between 15,000–18,000 feet (4,572–5,486 meters) using supplemental oxygen. Ever since he broke the speed record in the H-1, however, Hughes decided he would use the aircraft to break his own transcontinental record using the H-1. He thus had the aircraft modified with a longer pair of wings to accommodate extra fuel tanks (the shorter span, having been 25 feet, was replaced by a longer span of 31 feet, 9 inches). In the predawn hours of January 19, 1937, Hughes took off in the H-1 from Union Air Terminal (Hollywood-Burbank Airport). Retracing the route he took in Cochran’s Gamma, he landed at Newark Airport in 7 hours, 28 minutes and 25 seconds, having flown at an average speed of 322 mph.

From there, Hughes moved on to other ventures, from his round-the-world speed record of 1938, to building the XF-11 photo-reconnaissance prototype and the Hughes H-4 Hercules (better known by its more derisive nickname, the Spruce Goose), with the Hughes H-1 Racer going into storage at Hughes Airport in Culver City, away from prying eyes, yet maintained under Hughes’ orders in airworthy condition. In 1975, negotiations between Hughes Helicopters and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum resulted in the aircraft being sent to Washington D.C. for permanent display on the National Mall in downtown Washington, fitted with the long wings for its 1937 Burbank-Newark flight, with the short wings from the 1935 speed record, which Hughes had preserved, being sent to NASM for storage. Today, the aircraft is displayed disassembled at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, having been moved due to the ongoing renovations at the National Mall location.

In the years since the original H-1 went on display there have been reproductions and replicas of this aircraft made. One was displayed in the geodesic dome that once housed the Hughes H-4 “Spruce Goose” next to the RMS Queen Mary in Long Beach, California, while another built for the 2004 film The Aviator, starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Howard Hughes, is on display at the Santa Maria Museum of Flight in Santa Maria, California, and the late Jim Wright spent over a decade meticulously crafting an exact, airworthy reproduction of the H-1 that was so accurate it was called the second H-1 built. This, unfortunately, was lost along with Jim Wright in a 2003 flying accident, but the latest reproduction of the H-1 is being constructed at the San Diego Air and Space Museum.

The SDASM is no stranger to building reproductions of historic aircraft. In that same basement workshop, the museum constructed a reproduction of a Boeing P-26 Peashooter, a Gee Bee Model R Super Sportster, and the Bell X-1 Glamorous Glennis and restored original aircraft from a Mitsubishi A6M7 Model 63 Zero on loan from the Smithsonian to a damaged Ford Trimotor now displayed in the museum’s Pavilion of Flight. The museum’s H-1 reproduction is no different in terms of the meticulous detail that has gone into prior restorations and reproductions. But building the H-1 has been quite the challenge.

For one, the restoration team has had little to no engineering drawings to assist them in their project to recreate a one-off design. Much of the reference material has come not only from historical photos in the collections of the museum’s extensive archives, but also from modern day photographs of the original H-1 at the Smithsonian, thanks in large part to the cooperation between the two museums, as the San Diego Air and Space Museum is a Smithsonian Affiliate, with aircraft and other items on loan from the NASM.

In order to differentiate the Hughes H-1 reproduction from the original in the National Air and Space Museum, the SDASM has chosen to build their reproduction as the short-wing version flown by Hughes to set his record of 352 mph on September 13, 1935, which been depicted in film productions such as the aforementioned 2004 film The Aviator. Yet that has produced some challenges during the course of the project.

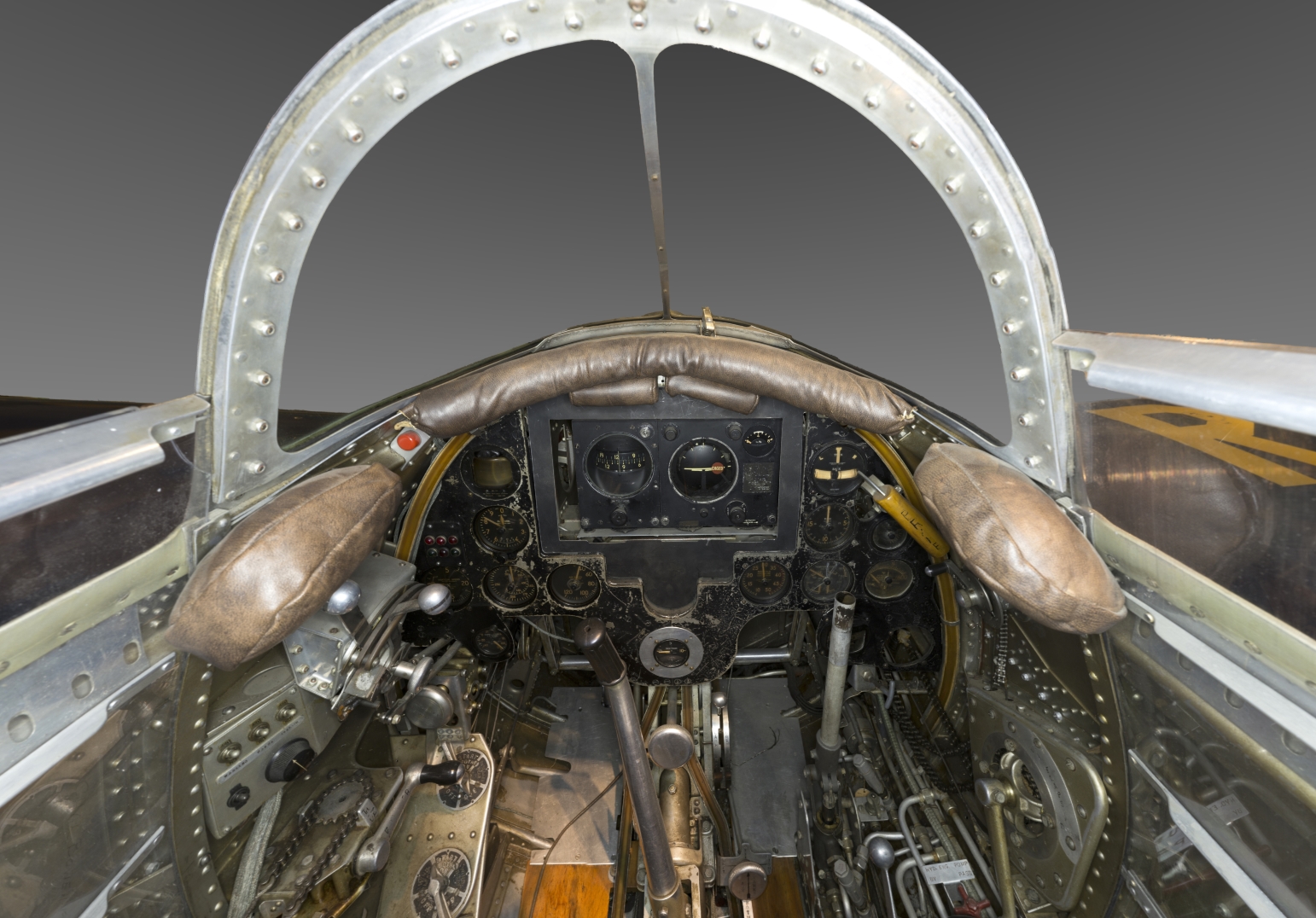

Among the most valuable reference photos have been those of the H-1’s cockpit. Being a one-of-a-kind aircraft, and one built for an owner that valued great privacy, there are not many period photos of the cockpit, let alone while it was under construction. While the Smithsonian had extensively documented the cockpit of the original H-1, complete with a panoramic view of the cockpit, the San Diego Air and Space Museum has recognized that just as the H-1 is displayed with the long set of wings from its 1937 transcontinental flight, the cockpit was modified for that flight to carry additional instrumentation, oxygen tanks, and radio equipment that was not present during the speed run. As such, they have sought to closely recreate the H-1’s cockpit as to how it looked during Hughes speed record in 1935.

For over ten years, the project has been underway, with museum volunteers having built a pair of wings to the same dimensions as the first set of wings on the original, and have built the fuselage, cockpit, and tail surfaces, along with the retractable skid rather than a wheel that Hughes had installed on the original H-1.

Another rare feature of the aircraft is the type of engine that powered it. The Pratt & Whitney R-1535 was discontinued by 1941 to focus on the production of more powerful engines during WWII, such as the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp. Fortunately, the SDASM has an R-1535 in their collection, and have earmarked it for installation in the completed H-1 reproduction. Though the engine has been test fitted to the airframe for alignment, it is currently removed in order for the volunteers to work on the engine mounts for final installation.

Like many aircraft its time, the control surfaces of the H-1 were covered in fabric. The rudder and elevators have their fabric doped, but the elevators have not been painted yet. The ailerons have yet to have this treatment.

It is too far to say when the Hughes H-1 reproduction will be ready for display, but when it is finished, it will likely be fully assembled and painted inside the basement of the Ford Building, then be disassembled in order to brought transported onto the display floor of the building. There it will stand as one of the most accurate depictions of this legendary aircraft.

If you wish to visit the Hughes H-1 Racer under construction in the San Diego Air and Space Museum, you can ask the front deck for a museum docent to give you a guided tour of the museum’s basement to see the aircraft under construction. It was through such guided tours that the photos for this article could be made possible.

For more information, visit San Diego Air & Space Museum – Historical Balboa Park, San Diego