It has been nearly two years since we last published an update on the reconstruction of Hawker Typhoon Mk.Ib RB396. As many readers will be aware, the Hawker Typhoon is among the rarest of World War II production fighters, with only a single complete example known to survive today. We have followed the progress of this ambitious project for several years (click HERE), and our earlier coverage remains available through the link provided. The Hawker Typhoon Preservation Group is working to change the aircraft’s scarcity by reconstructing RB396, beginning with the original rear fuselage. Project lead Sam Worthington-Leese has now provided a detailed update on the current state of the work.

With the rear fuselage now complete, attention has turned to reconstruction of the tailplane. This marks the first in a planned series of regular progress reports charting work carried out during the opening two months of this phase. Supporters of the project will already have seen this update in the most recent newsletter circulated a few weeks ago, reflecting the group’s commitment to keeping its supporters closely informed. As previously outlined, the Aircraft Restoration Company (ARCo) was required to make several adjustments to the existing tail jig. The jig had originally been built for a different tail, and although Typhoon tails were theoretically identical, they were effectively hand-built, making minor variations inevitable. A trial fit of RB396’s tail revealed that changes were needed to the tailplane fixing points and to the alignment of the rudder post. These modifications were completed during September, after which the tail section sat correctly and securely within the jig.

ARCo also proposed more substantial changes to the jig to better support the rebuild. The upper tail fin framework, originally intended for a Tempest rather than a Typhoon, was removed, and additional stiffeners were installed to maintain squareness. The lower half of the jig was mounted on a rotisserie structure, allowing the entire lower tail monocoque to be rotated to improve access during restoration. This approach mirrors the design of the larger rear fuselage jig used earlier in the project. Prior to removing the upper fin framework, splice plates were fabricated so it can be refitted later and adjusted for a Typhoon fin when required. All of this jig modification work was completed during September. The jig now allows the principal structural elements of the tail, including frames and diaphragms, to be removed individually for refurbishment, repair, or replacement, while the remainder of the structure remains fully supported. This method preserves accurate alignment and positioning, avoiding the need for multiple jigs. However, it also limits how much can be dismantled at any one time, as only one or two components can be removed before they must be reinstalled to maintain structural integrity. As a result, visible progress can appear slower than if the entire structure were stripped at once.

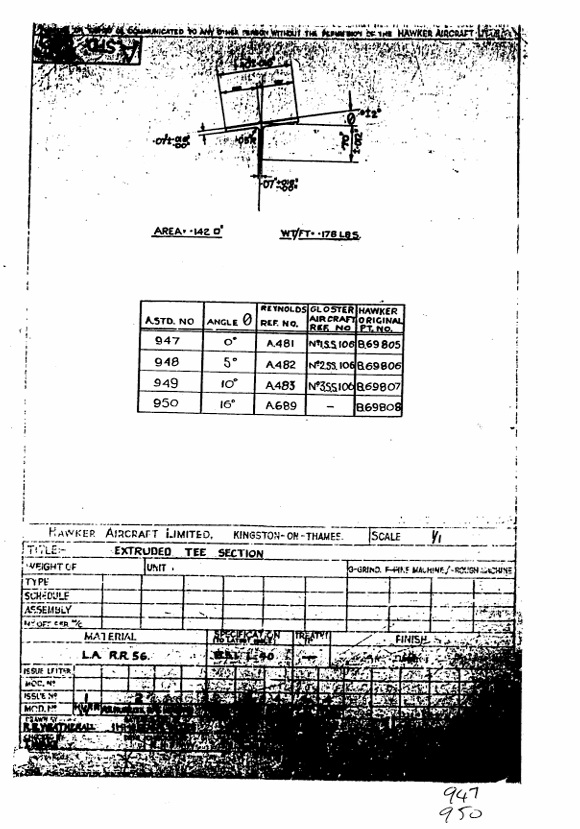

Despite the focus on jig work, ARCo also began rebuilding the lower tail monocoque during September. The fin and upper port skin were removed to allow an internal inspection of the tail and upper diaphragm. While there had been hopes of examining the internal tail structure of Typhoon MN235 for reference, the RAF Museum has confirmed that access will not be possible until mid-2027. Fortunately, inspection of RB396’s tail confirmed that all internal structural elements are present. Further research was required into stringer 7, a “T”-section stringer not used in the rear fuselage and for which no specific drawing was available. Hawker relied on a comprehensive set of standard brackets, extrusions, and procedures documented across 2,352 A.Std drawings, some of which no longer survive. Measurements taken from stringer 7 were compared against all available A.Std “T” sections until a match was identified, a process that proved time-consuming but ultimately successful.

The upper diaphragm, its associated brackets and extrusions, and the intermediate frame bulkhead have since been removed. While the intention is always to reuse as much original material as possible, corrosion within the tail has affected the majority of components, necessitating the manufacture of replacements. The original parts remain suitable as patterns, however, and combined with surviving drawings, they provide ARCo with a reliable foundation for new manufacture.

ARCo is currently using the last of its British-specification L163 aluminium stock for this work, but will soon transition to American-specification 2024 material, as the original British specification has largely fallen out of use. During October, attention shifted to removal of the tail leg and its surrounding structure. Corrosion and damage to the main attachment pin meant the tail leg could not be extracted without risking distortion to the surrounding framework. As a result, the entire cradle section, complete with the tail leg, was removed from the monocoque. Once clear, improved access allowed the attachment pin to be treated with penetrating oil and heat, enabling its successful removal and separation of the tail leg from its cradle.

As with the rear fuselage rebuild, a timelapse camera has been installed to document progress on the tail, and footage covering the first two months of work is now available via the link below. ARCo’s next focus will be the cradle subassembly, which must be completed and refitted to the monocoque before work advances to the next stage of the reconstruction. To support this restoration, click HERE.