In 1938, Douglas transports flew a distance of 13.5 times around the world each day (that’s more than 336,000 miles). Yes, just three years after the first flight of the Douglas Sleeper Transport—the original Douglas DC-3—those airplanes were busy aloft, serving their purpose to connect folks and move goods via commercial aviation. Even more amazing, perhaps, is the fact the DC-3 still circles the globe in ambitious ways to this day. Witness the efforts of the D-Day Squadron returning to Normandy and the Spirit of Douglas launching on an incredible world tour, and you’ll begin to grasp the airplane’s longevity and suitability to its fundamental missions.

Prior to the DST’s first flight, the Douglas Aircraft Company had witnessed no small amount of success with its predecessor, the Douglas DC-2—but it was hard won. Carrying 14 passengers and featuring a wingspan of 85 feet, the DC-2 brought DAC out of the red as a business. Building the prototype DC-1 cost the company between $307,000 and $325,000 (sources vary)—far more than the $125,000 TWA paid for it. The first 25 DC-2s went at a total loss of $266,000, but the operation came into the black with the 76th DC-2 built, around mid 1935.

At that point, Donald Douglas had been named president of the newly formed Institute for Aeronautical Sciences—and tapped to deliver the Wilbur Wright Memorial Lecture at the Royal Aeronautical Society on May 30, 1935, titled, “The Development and Reliability of the Modern Multi-Engine Airliner.” He based his paper supporting the speech on the aircraft he had close to the finish line, a new model which he revealed at the dinner: “I am now building to replace these [DC-2s] a type which will carry 32 passengers by day and 16, with full sleeping accommodation, including private dressing rooms, by night.”

Douglas had essentially been talked into the new model by American Airlines President C.R. Smith. Initially, “Doug” stood firmly against the sleeper concept. But a phone call back in 1934—that cost Smith a reported $335.50—convinced the reluctant aircraft manufacturer to take on the new version. Recall that in 1934, DAC had not yet recouped its investment on the DC-2, though it had a full order book, giving it a line of sight to that happy point in the ledger. But Smith was in a tough spot, facing the bankruptcy of his airline if he couldn’t secure an airplane that would put him ahead of his competition already flying the DC-2. On July 8, 1935, Doug received the telegram from Smith placing the order for the first 10 of 20 DST airplanes for $795,000. The Texas businessman could put forth this money thanks to a $4.5 million loan courtesy of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation—a discount lending arm of the Federal Reserve Board begun in 1932 and intended to help American industry lift itself out of the Depression’s doldrums.

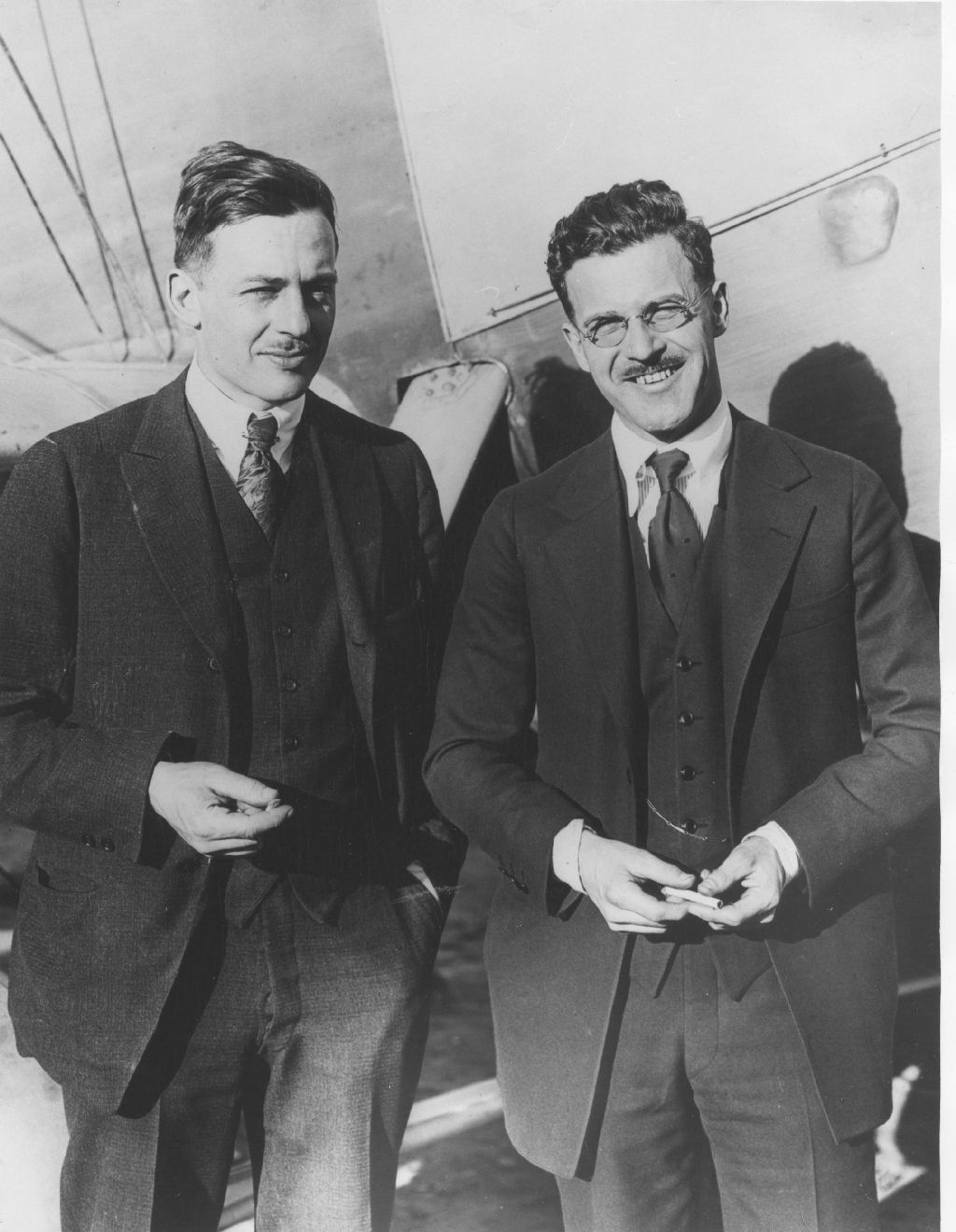

The initial test flight of the DST took place on December 17, 1935—the 32nd anniversary of the Wrights’ famous launch—purely by happenstance. Though the weather in Santa Monica, California, typically stays nicer through the winter months than, say, Brooklyn, where Doug was born, the crew had to pick a cool, clear day to obtain the best results. Carl Cover—who had also commanded the first flight of the DC-1 and DC-2—joined co-pilot Fred Collbohm, and engineer Ed Stinemann, and taxied out at Clover Field (now KSMO) around 3 pm, taking off towards the water. By that time of day, even in SoCal, the December sun streaked low into the sky, sending its light into the split cockpit windows.

American accepted its first DST, NC14988—the very same airframe that had flown the first test flight as NX14988—on April 29, 1936, just more than four months later. It flew on two Wright Cyclone SGR-1820-G-5 powerplants, and had 112.5 flight hours at the time of delivery. Named the Flagship Texas after Smith’s home state, and that of the headquarters for American, NC14988 plied the skies for the company through March 1942 when it was sold to competitor TWA for use hauling cargo under contract for the Army. It transitioned to full-on war service later in 1942 with the 24th Troop Carrier Squadron. The original DST unfortunately came to its end just a few months later, destroyed in an accident during poor weather near Knob Noster, Missouri, on October 15, 1942.

Not quite seven years in service, yet her first flight launched a transformational chapter in aviation history—in fact, in human history—as no aircraft has so changed our world from such a quiet beginning.