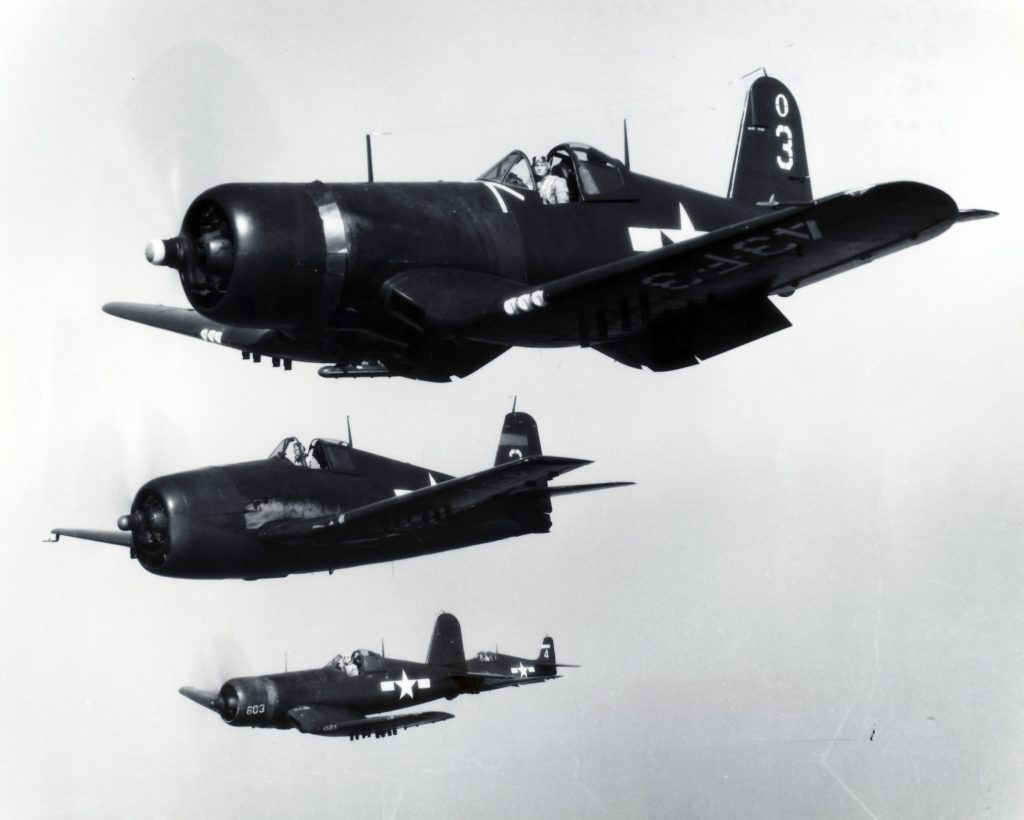

In this author’s opinion, debating the best fighter of World War II is pointless. It is subjective and often based upon one’s nationality, preference in military services, or particular unit or pilot. In the case of the Pacific War, the title of best fighter often comes down to the Vought Corsair and Grumman Hellcat. If one simply examines cold, hard numbers, the Hellcat comes out on top with 5,163 aircraft destroyed and a 19:1 kill ratio versus 2,140 and 11:1 for the Corsair. Dig deeper, though, and the Corsair reigns supreme.

On October 1, 1940, two years before the Hellcat first took to the sky, the Corsair became the first U.S. fighter to exceed 400mph in level flight. This was made possible in part by the 2,000hp Pratt & Whitney XR-2800 radial fitted to the aircraft. Post-war interviews with Japanese soldiers revealed that the Corsair was the most feared fighter by ground troops. In November 1945, the 12,275th and final Hellcat was produced, but Corsair production would continue for an additional eight years. Well into late 1953. And lastly, and this is likely to be the greatest testament to a design, the Corsair saw combat well beyond World War II, seeing service in Korea, Indochina, Alegria, Egypt in the 1950s, and Central America in 1969.

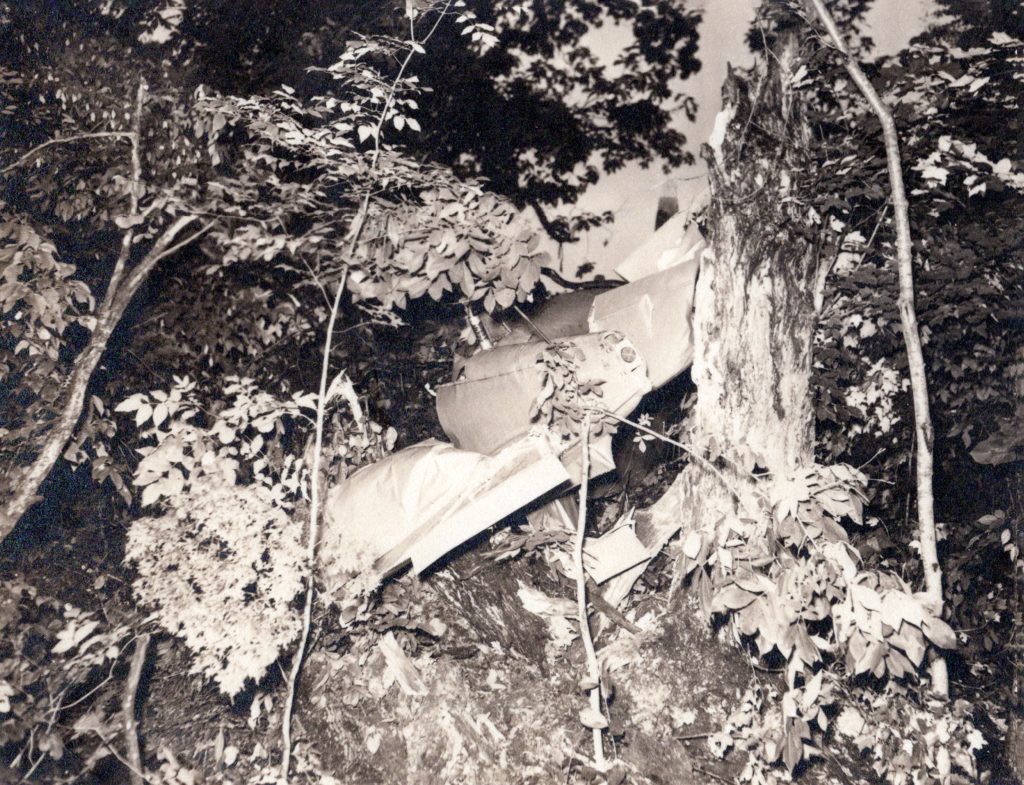

This stellar career, however, got off to a rough start when XF4U-1 BuNo 1443, the one-and-only prototype at the time, received substantial damage in an off-airport landing on July 11, 1940. The following day, The Record Journal ran a small report on the accident, which read in part, “A test flight experimental plane was badly damaged here this afternoon when it made a forced landing on the Norwich golf course. The plane, a low-wing, all-metal job, landed on the 14th fairway, taxied along about 250 feet, then crashed into a tree, ripping off part of the wing and tailed over in a wooded gully.” The same day, The Waterbury Democrat reported that 26-year-old Boone Guyton, who was slightly injured, told reporters that he ran out of fuel.

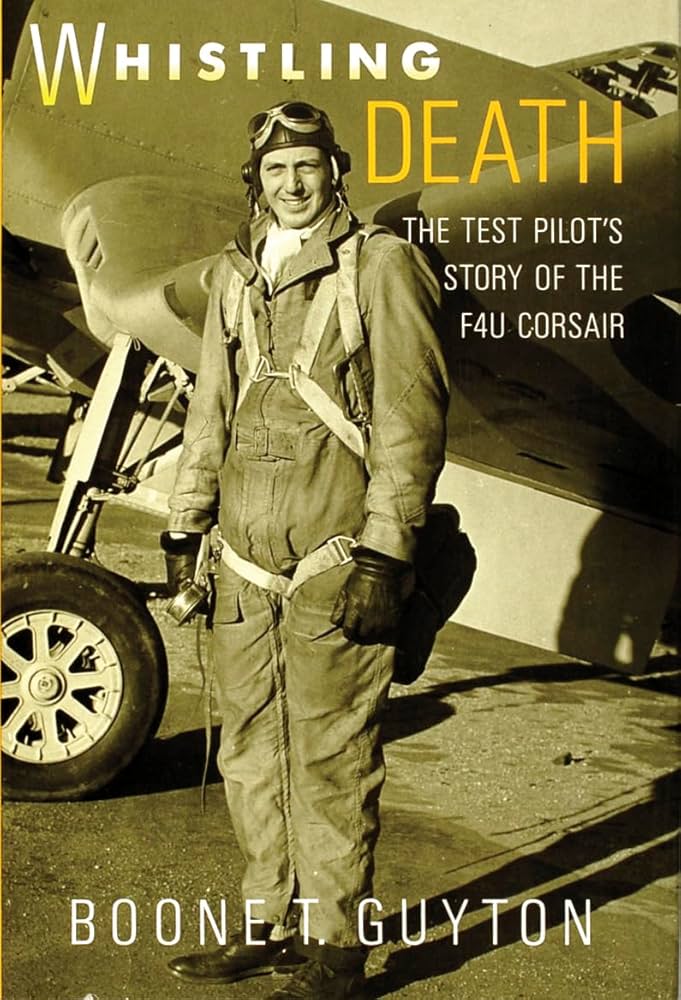

These reports are typical of a newspaper that has to tell a sensational story in just a few hundred words, but there was much more to the story, and Boone Guyton related that story in his book, Whistling Death: The Test Pilot’s Story of the F4U Corsair (Book available on Amazon, click HERE). Guyton had made his first flight in the XF4U two days prior, and in his book, he wrote about the conversation about the weather he had with Vought Chief Test Pilot Lyman A. Bullard, “In the afternoon, with the XF ready, the irksome weather still threatened, but as yet there was no rain. Bullard and I talked it over.

‘Think you can complete the cabin pressure tests before it closes down? With this weather, anything at altitude is out.’ Through the window, I could still make out the radio towers that are over 3 miles away. ‘It’s worth a try, I can always knock it off.’ My decision”. Naturally, Guyton chose to fly. Once airborne, he leveled off at 500 feet. He set the power at normal rated power- 2,500rpm and 44 inches in the neutral blower. By the time he started his third run, the weather had worsened considerably, but he still proceeded with the test. It’s likely in a different time, Guyton would have likely aborted the test, but the clouds of war were on the horizon, but the engineers needed the data, so he pressed on with the flight. For this final run, he went to maximum military power- 2,700rpm and 52.2 inches. He was vigorously taking notes when he saw the first streak of rain on the windscreen. Then, suddenly, a black line of clouds appeared in his path. Now he had no choice. He aborted but also realized he’d flown himself into a corner. He attempted to find a way to an airport, any airport, but every avenue of escape was blocked by scud and heavy rain. Even though it was the middle of the afternoon, the skies and the Corsair’s cockpit were forebodingly dark. Then a light suddenly lit up the cockpit. Guyton wrote, “Trouble in an airplane emergency- when things have gotten snafued- tends to escalate, and rapidly. As the fuel warning light blinked red through the dark cockpit, I quickly switched to reserve and felt the terror of the moment- a trapped rat! A catastrophe was building and there was no place to go.”

As he circled lower and lower, desperately looking for a place to land, he saw nothing but trees below. Since knocking off his run, the rain had increased in intensity to the point where he was looking down more than ahead. Then Providence stepped forward. Almost simultaneously, the rain let up, and Guyton spotted a church steeple and a few seconds later the outline of a golf course. As he dropped below the height of the steeple, he slid the canopy back and steepened his bank to keep the golf course in sight. It was the Norwich Golf Course, where 18-year-old caddy Alex P. Kuczienski had been watching the Corsair since it first appeared overhead. It was obvious to the teenager that the Corsair was in trouble.

Guyton related the landing in his memoir, “With the light rain beating against my face, I leaned out, followed the dim pattern of the golf course for the longest, flattest fairway, and closed the decision. On the green of the straightest and longest fairway, I could make out the flag. It was hanging limp- no wind. Behind it was a stand of heavy woods, but at the far end, the fairway was wide open- a good approach. I would land toward the green.” The fairway that Guyton chose was the 14th, and Kuczienski was already running in that direction because he knew it was the longest and most suitable place to land. While Guyton was setting up his approach, he noticed out of the corner of his eye that the once flickering fuel light had turned solid. He had precious few minutes of fuel remaining. He couldn’t worry about fuel now. He lowered the landing gear and flaps and set the prop in low pitch. Guyton continued in his memoir, “Dropping down just above the course, I hung the Corsair on its prop, slow as I dared; I wanted to get down to the last flyable knot. Then I jerked the throttle full off. The big fighter hit hard a quarter of the way down the fairway. It headed straight for the green, and I got on the brakes fast. Relief at being safe on the good earth was instant, sweet- and totally false.

Slick form the wetness, the fairway that appeared so inviting was a skating rink. Braking had no effect, as the XF’s smooth tires held contact. I was a hundred yards from the green, and I knew I was headed for the bank of trees beyond.” As the XF4U skidded and skipped along the fairway with unchecked abandon, Guyton stomped a boot full of rudder to induce a ground loop, but it had no effect. Seconds before he crashed into the trees, Guyton undid his parachute harness, shut off the ignition, cut the fuel, grabbed the bottom of the stick, and pulled himself down into the cockpit. That final action, Guyton said, probably saved his life, for when the fighter plunged into the trees, which concealed a large ravine of rocks and boulders, he was in for a rough ride. “Paradoxically, the trees were both destructive and helpful, but at the exact moment, my only thought was survival. As the sturdy, tough saplings bent and split, they arched the XF into the air as though it were flung from a sling. As it flipped inverted, I felt a hammering at my head, hard thumps against my shoulders, and then- nothing. Its momentum barely broken, the big fighter crashed, inverted, down through the trees, slid backward down the steep slope of the ravine, and smashed into a huge tree stump.” Guyton related. Kuczienski and some friends arrived at the crash site moments later, where he saw the wings “clipped off by a large tree and by boulders.”

It’s unknown whether Guyton suffered any loss of consciousness in the crash, but he admitted that he was “foggy” and that his awareness returned slowly. All too soon, though, panic began to set in as he found himself in total darkness, hanging in his straps, and unsure if he could extract himself from the cockpit. Even though he shut off the fuel just before impact, he was worried about a fire. He braced himself the best he could, released the harness, and fell only six inches into wet branches. Then from somewhere outside his darkened universe, he heard a voice, “Hey, you alright down there? Can you get out?” It was Kuczienski. Guyton replied, “I think so, I’ll let you know.” Guyton’s injuries were minor, and even though he had released his straps, he was still trapped in the darkness of the inverted wreckage, but after digging a small opening in the damp soil, he crawled out of the cockpit and made his way to the top of the ravine. As he spoke to an elderly police officer, who arrived on scene surprisingly fast, Guyton looked down at the “sad remains” of what was then the only Corsair in existence and silently admonished himself for the string of decisions that led to that moment. He ended up spending the night in Norwich under a doctor’s care; his injuries included a mild concussion and various lacerations and contusions.

Guyton was naturally harder on himself than anyone else, and in the days that followed, little was said about the crash. Bullard told him, “Hey, kiddo, don’t let it grab you. That’s part of what they pay us for you caught some bad luck.” An engineer said, “Don’t worry, we can always fix the airplane. You got it down, and here you are, that’s what counts.” The night after the accident, the fighter was hauled out of the ravine, and “Pop” Reichert, a Prussian who headed the shop, told Guyton they’d have the fighter flying again in three months. “Working around the clock, the indefatigable crew, backed by engineering and production, had 1443 restored and ready for flight by the last week of September. Reichert’s word was pure gold.” Guyton wrote.

Fast-forward thirty-six years to New Haven, Connecticut, in May 1976, where a reunion of Corsair test pilots took place at Piccadilly Square Restaurant. The brainchild of James E. Malarky, assistant head of field operations under Jack Hospers during the war years and then-manager of Tweed-New Haven Airport, the reunion attracted two dozen former Corsair test pilots. The reunion was held on the weekend of May 29-30, which is not coincidentally the anniversary of the first flight of the XF4U-1 Corsair. Throughout the weekend, the pilots regaled each other with flying stories with a youthful exuberance that belied their graying and balding heads. Those young men of yesteryear helped develop America’s first 400-mph fighter that helped American and allied pilots turn the tide of war against the Axis powers.

On Sunday, June 1, a then 54-year-old World War II Navy veteran turned postal worker read about the reunion in the New Haven Register. It took him back to a rainy July afternoon in Norwich, Connecticut, where he saw a silver and yellow Corsair crash into a stand of trees at the Norwich golf course, where he’d been a caddy before the war. That postal worker was, of course, Alex P. Kuczienski. He wrote a letter to Malarky, who forwarded it to Guyton, who was 63 at the time and still working for Vought.

It should be noted that on the day of the accident, Kuczienski never learned the name of the battered and bleeding pilot who crawled out from under that wrecked Corsair. That information revealed itself when he received a letter from Guyton in mid-June. On Thursday, June 24, 1976, Malarky arranged for Guyton and Kuczienski to meet once again, under much better circumstances, at Tweed-New Haven Airport. It had been many years, but the memories were still just as fresh as a newly manicured golf course. Like the 14th fairway in Norwich.

Related Articles

Stephen “Chappie” Chapis's passion for aviation began in 1975 at Easton-Newnam Airport. Growing up building models and reading aviation magazines, he attended Oshkosh '82 and took his first aerobatic ride in 1987. His photography career began in 1990, leading to nearly 140 articles for Warbird Digest and other aviation magazines. His book, "ALLIED JET KILLERS OF WORLD WAR 2," was published in 2017.

Stephen has been an EMT for 23 years and served 21 years in the DC Air National Guard. He credits his success to his wife, Germaine.