By Randy Malmstrom

Since his childhood, Randy Malmstrom has had a passion for aviation history and historic military aircraft in particular. He has a particular penchant for documenting specific airframes with a highly detailed series of walk-around images and an in-depth exploration of their history, which have proved to be popular with many of those who have seen them, and we thought our readers would be equally fascinated too. This instalment of Randy’s Warbird Profiles takes a look at the Supermarine Spitfire Mk.IXc on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington.

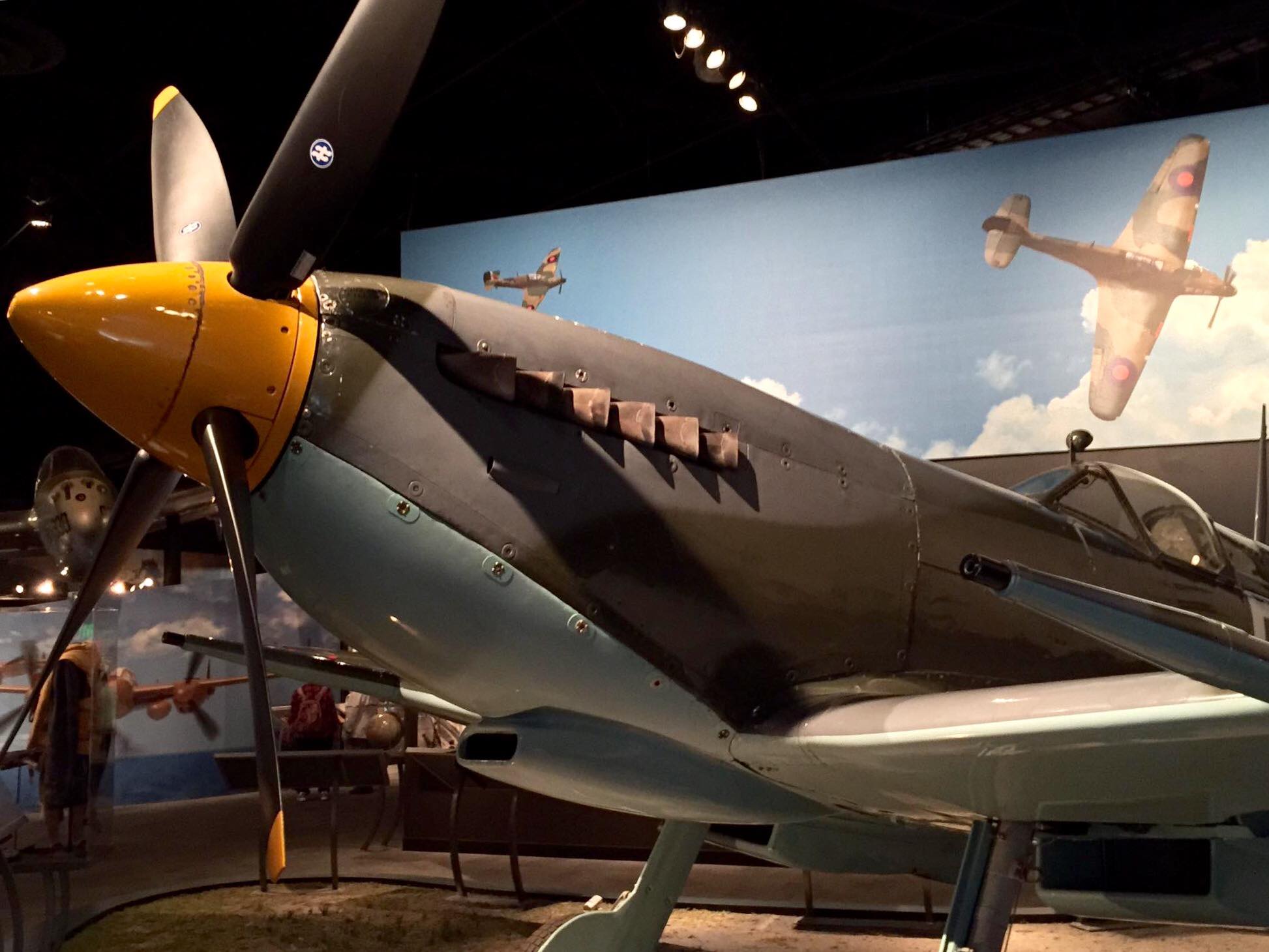

Supermarine Spitfire Mk.IXc, RAF s/n MK923. This particular aircraft was built in March 1944 at Castle Bromwich Aircraft Factory with the first test flight carried out by British air racer and Vickers-Armstrong test pilot Alexander Henshaw, MBE, on March 18, 1944. It was assigned to 126 Squadron RAF at Sawbridgeworth, Hertfordshire, on May 10, 1944, and was given the code 5J-Z. Its first action was on a shipping reconnaissance sortie on May 28, 1944, flown by Squadron Leader W.W. Swinden. To my knowledge, it last saw combat action in WWII on August 14, 1944, when pilot Officer Risley shot down two Bf-109s south of Paris. It left 126 Squadron on December 30, 1944, after the squadron was relocated to Bentwaters.

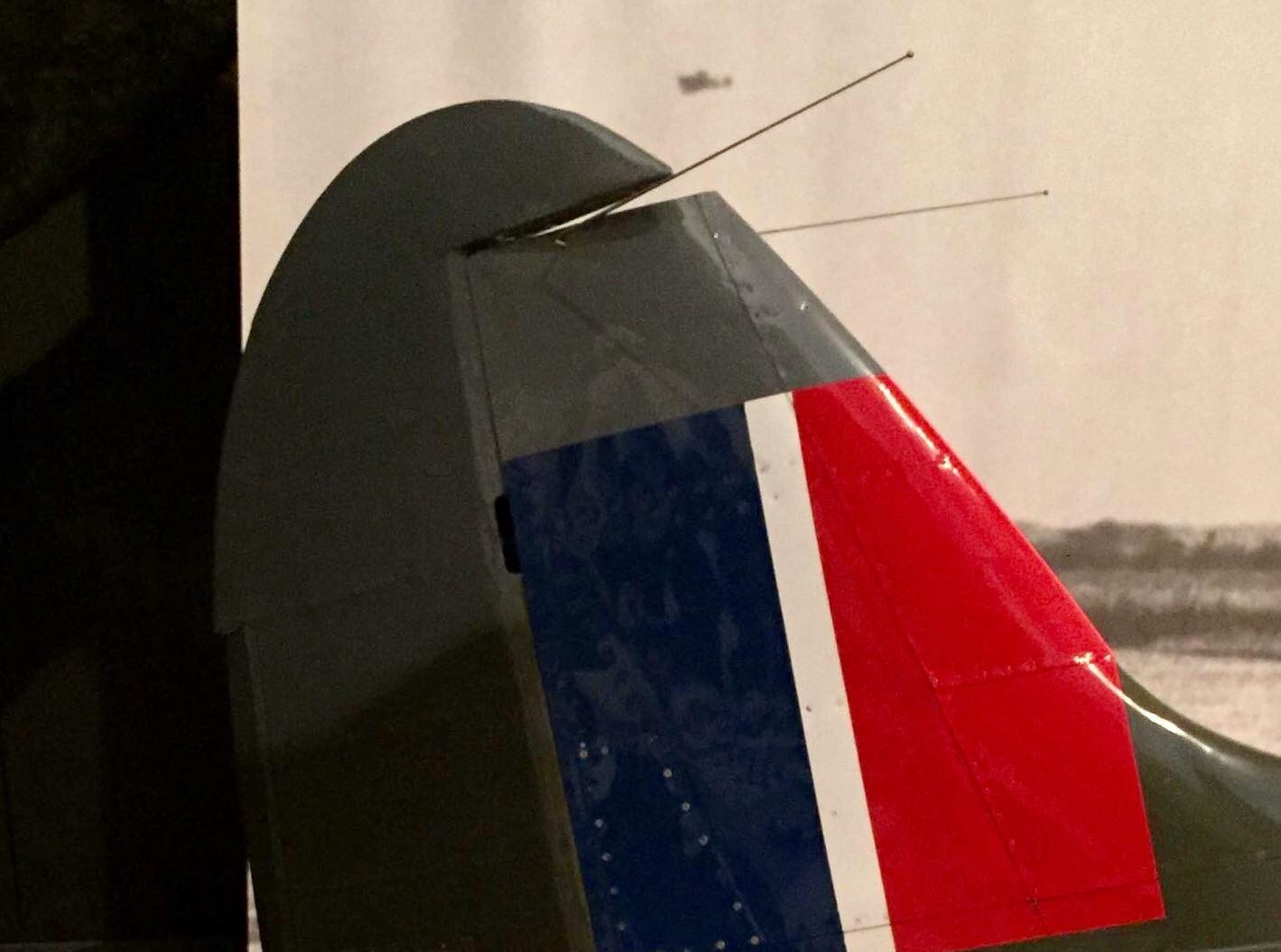

It went into storage and repair at various locations through the end of World War II. It was taken on charge by the Dutch Government on May 19, 1947, with the designation “H-104” and was delivered to the Dutch East Indies, where it flew 24 missions against nationalist rebels. It was sold to the Belgische Luchtmacht (Belgian Air Force) in March 1952 and was given the designation “SM-37” and flew as an armament trainer. It was declared surplus on April 25, 1958, and given the Belgian civil registry OO-ARF. The company COGEA Nouvelle SA used it as a target tug under contract with the BAF at Middelkirke Airport near Oostend, Belgium. It was one of four Spitfires leased by COGEA to 20th Century Fox for the 1962 film “The Longest Day” and painted with D-Day invasion stripes and “Isle de France” No. 340 Free French Squadron RAF markings and with the code GW-U (camouflage not totally accurate and the lettering and Cross of Lorraine different from that used by 340 Squadron). The aircraft were coordinated by former Free French Spitfire pilot Pierre Laureys, who flew with 340 Squadron (Laureys participated in Operation Jubilee at Dieppe and scored two victories) and, in March 1943, scored two more victories against Fw-190s, damaging a third, and he made an emergency landing on the English coast after his Spitfire was hit. He was promoted to Captain at the time of Operation Overlord and at war’s end was credited with five victories and numerous ground targets destroyed.

This aircraft was purchased in 1963 by actor Cliff Robertson. It went through a series of rebuilds, and the Rolls-Royce Merlin 66 engine was replaced by a Merlin 76 with a four-bladed Rotol propeller. It was flown from 1972 to 1994 by Royal Canadian Air Force Spitfire pilot Jerry Billing, who, with over 52 years, holds the record for most flying time in a Spitfire. In 1996, it was sold to Craig McCaw and ferried back to California by well-known pilot Bud Granley (a Washington resident), who was to be its pilot for the remaining years of its flight time. The aircraft went on static display at the Museum of Flight in 2000 (due to “loose rivets“). My photos.

Supermarine (a subsidiary division of Vickers-Armstrong) had manufactured racing seaplanes before World War II. R.J. Mitchell, the Spitfire’s designer, wanted the aircraft type nicknamed the “Shrew” rather than “Spitfire” (an old English term for someone with a strong, fiery character). The Spitfires were equipped with Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. The fuel tanks are directly in front of the cockpit, so pilots jumping out of flaming aircraft may have received what doctors called “Airmen’s Burn” on the hands and face. The windscreen is bulletproof glass, while the side panels are Perspex. The rear-view mirror is mounted outside the cockpit.

The control column was pivoted about a foot from the top and was topped with a spade grip or yoke. Within the spade grip was a bicycle-type brake lever which controlled pressure to the air brakes, with differential application by movement of the rudder pedals. The weapons were fired using a rocker switch (this replaced the single button switch) on the yoke or spade grip: top was machine guns, bottom was cannons, and middle was both. The pilots used the acronym “BBC” for Brownings (top), both (middle), and cannons (bottom). The iconic elliptical wings reduced induced drag but were harder to build.

There were many variants to the Spitfire produced during the war (much was learned during the Battle of Britain for one thing), upgrading armament (combinations of Browning .30 then .50 cal. machine guns and Hispano 20 mm cannon), upgraded powerplant, a teardrop canopy was added for better visibility, clipped wings and a cut-down rear fuselage for low-altitude combat (increased roll rate), and an improved carburetor to help prevent engine cut-out at negative G’s.

About the author

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.