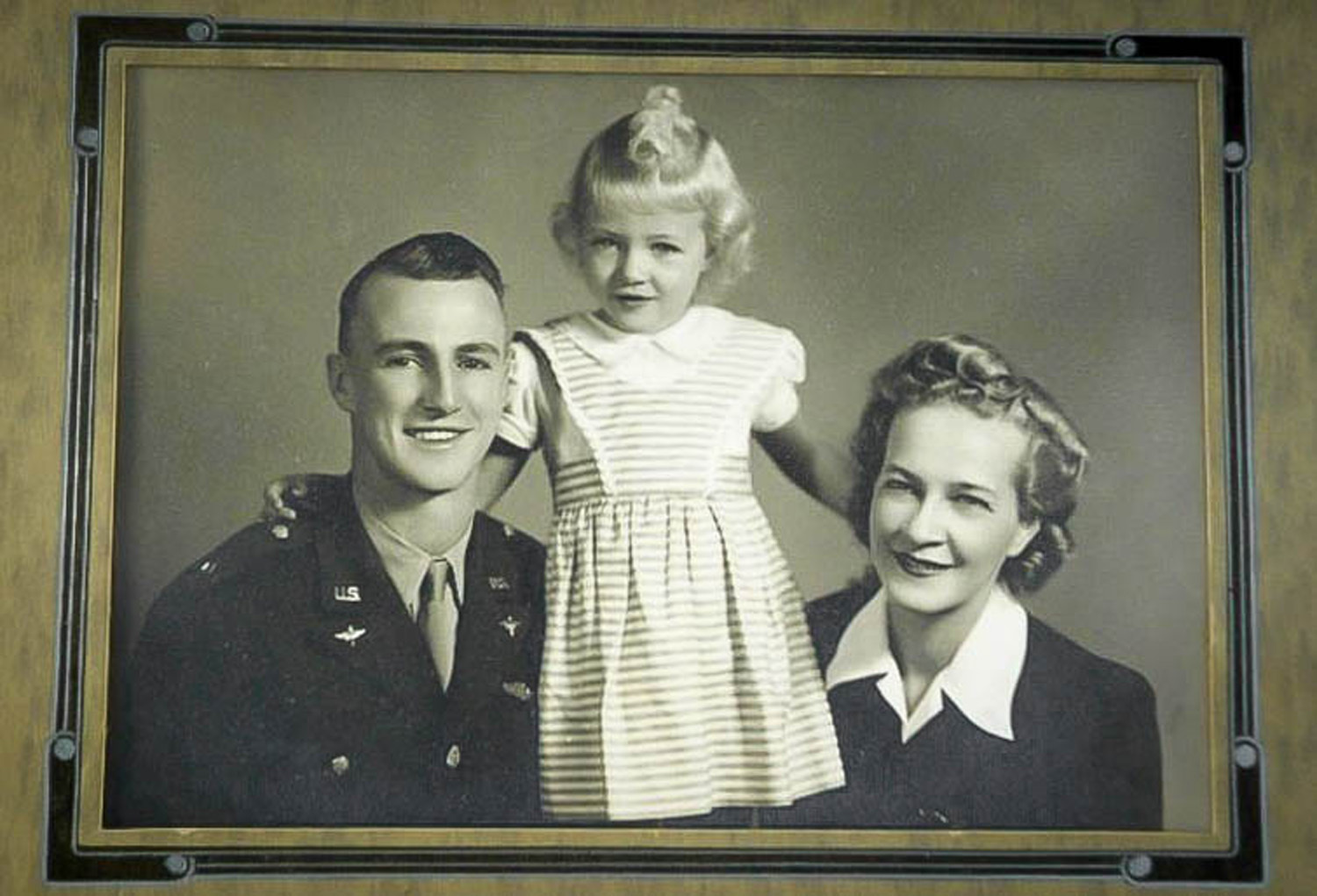

Evidence of the source of her pain rested within the contents of a few boxes of loosely sorted photos and scattered war medals, along with some stories reluctantly voiced by her father’s fellow crew members. Everything revolved around a fateful day in December of 1943. The weather had been perilous for weeks, but for Capt. Carl “Cully” Ekstrom and his seasoned P-47 Thunderbolt bomber escort crew, it was just another mission. On their way back to base after flying cover for a group of B-17 Flying Fortresses, Ekstrom and his formation encountered a gaggle of German FW-190 fighters. The ensuing battle took down three of the four P-47s, including Ekstrom’s, who despite shooting down one of the Luftwaffe fighters, succumbed to the exploding shells of ground-based anti-aircraft fire. That ill-fated day, Thomson, who was only five years old, lost her father.

The feeling of loss endured and affected Thomson from grade school through college, while casting a shadow on the rest of her life. “At a young age I understood what had happened; I knew that my father was killed in the war and that he was not coming back,” Thomson explained. “But, being that I was only five, it was difficult to process — we did everything with him, we followed him to all his training assignments and duty stations. “As I progressed through school it became more and more evident that something was missing inside of me. Though there were never any overt problems, it was a negativity and reluctance that perpetuated the way that I viewed myself.”

Unlike luggage that could be set aside, Thomson carried these feelings with her every day. It was like a dull hum that occupied her subconscious. Many times throughout her upbringing, Thomson would ask her mother about her father, probing for details about his time in the military and his last flight. “My mother took it very hard; she had lost the love of her life, and for that, she didn’t talk about it,” Thomson said. “Because of the hurt it placed on her, nearly all the memories were packed away, except a couple of photos and a necklace she wore, which bared one of the two Golden Glove medallions that my father had won during his boxing career.”

Throughout college and for nearly five decades, Thomson would slowly piece together details about her father, filling small amounts of the void along the way. It wasn’t until a happenstance meeting in 2014 that finally brought the story full-circle. “Along my journey to discover myself through the legacy of my father, I met a gentleman named Frank Cronin,” Thomson said. “Frank is a military enthusiast, who through his love for country and history found a perfect way to commemorate our nation’s fallen aviators — by building historically accurate models of the planes they flew. “Frank, knowing that my father had been shot down in France, asked if he could honor his sacrifice through one of his creations. I, of course, obliged at the kind gesture but, unbeknownst to me, this would lead to more information in one year than I had gathered in 50. The series of events sparked from the model aircraft are nothing short of amazing.”

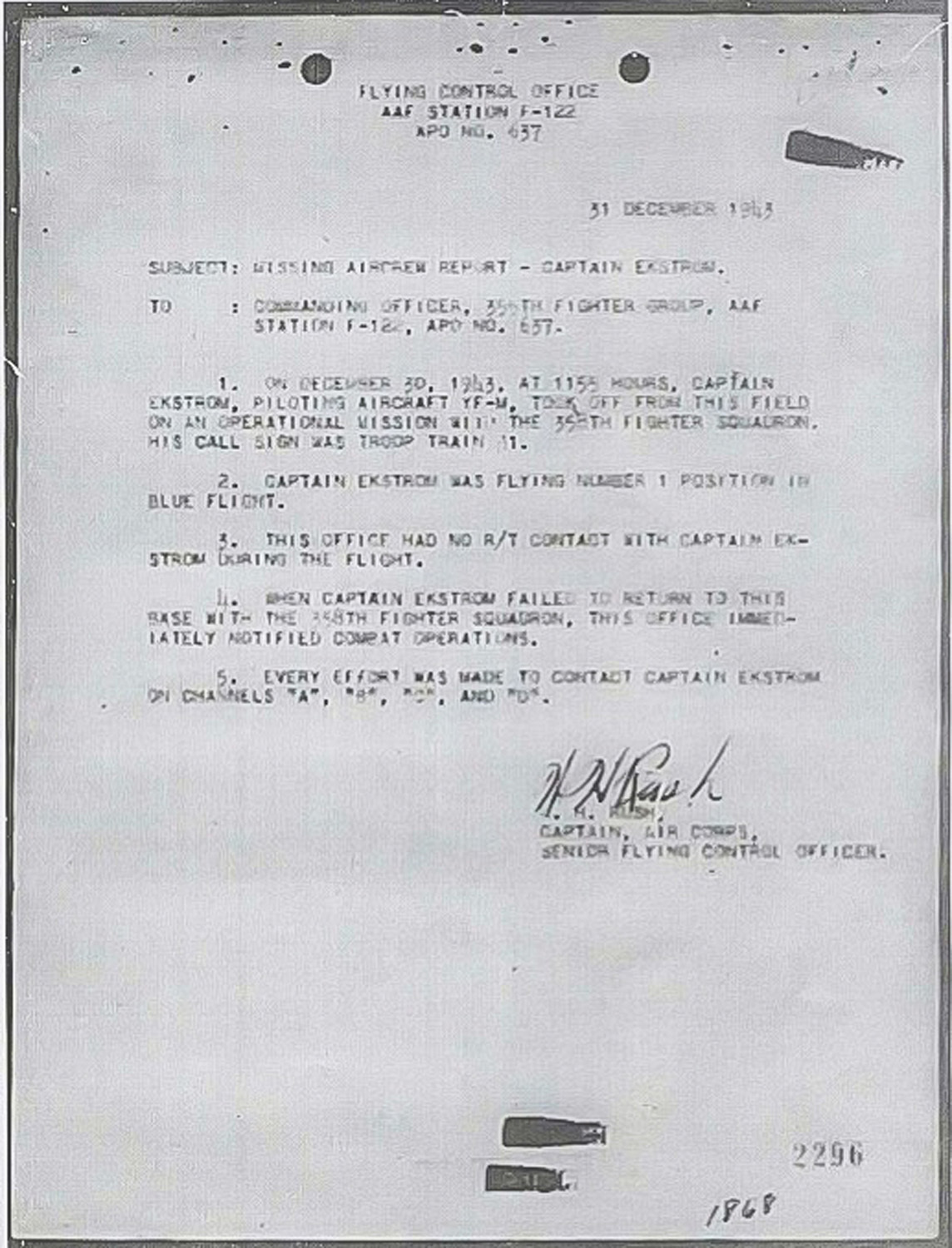

After recreating Ekstrom’s Golden Glove-adorned P-47 Thunderbolt, or the “Jug” as it was known to its pilots, Cronin placed photos of his artwork on an aviation enthusiast website. Within a short time, thousands took an interest in the replica, but none were more inspired than Steve Fenker, a relative of Lt. Charles Wambier, one of Ekstrom’s fellow crew members that had also died on that December afternoon. Until that point, Thomson had no information about the day her father had been shot down, let alone any on the other members in her father’s illustrious fighter group. Come to find out, Fenker was “obsessed with the details,” and had a treasure trove of information on the final moments from the mission. “The support for the Ekstrom P-47 was outstanding, I had no idea what it would arouse,” Cronin said. “I had people from all over the world commenting on the story behind it, and with the inclusion of Fenker’s accounts, it made the connection seem surreal.” Fenker reached out to Cronin, who then contacted Thomson. “Talking with Steve for the first time overwhelmed me with emotion — the amount of coincidences in our family history and our search for details was astounding,” Thomson said. “Not only did he have details about my father, he had a copy of the missing aircrew report, which also included a first-hand statement of witness attached to it. “The information in the reports was so detailed, I felt as though I was a part of the battle. This was a major milestone in my life.”

Right when it seemed like there was nothing that could make the story more complete for Thomson, Fenker had one more surprise.

“Steve and I had spoken many times after our initial meeting, but one thing that stuck out to him was the fact that I had never been face-to-face with one of the P-47s that our late relatives had flown,” she said. “With that, he connected me with the 355th Fighter Group reunion committee and said that he ‘would love to pay for my husband and me to fly out to Tucson (in Arizona) during their next gathering.’ Included during that time would be a chance to witness the Air Force Heritage Flight demonstration, which included the Thunderbolt.” Humbled by Fenker’s generosity, she jumped at the opportunity and joined in on the reunion.Thomson and her husband were greeted in Arizona by more than 40 veterans of the fighter group. Each day, she gathered more information on her father and his unit, while sharing with others the heartache of those who they had lost.With each conversation she felt more “at peace with the tragedy” and awed at how much “the experience was a tremendous help.”

Among those that she spoke with was 94-year old Bill Lyons, a World War II fighter pilot with the 355th FG, who happened to know her father. “Ekstrom was your father?” Lyons exclaimed. “I knew Ekstrom … everyone talked about him. He was a great pilot.”Thomson was taken aback by the kind words and amazed that the shroud of mystery surrounding her father was finally being lifted.Then, on the last morning of the reunion and prior to the commencement of the Heritage Flight demonstrations, Ekstrom finally got her chance to meet the iconic P-47.“Laying my hands on the very model of aircraft that my father had flown during his last days settled the void that had been looming for decades,” Thomson said, shedding tears. “It closed the chapter on my search for closure; that missing piece that I had since grade-school was finally resolved.”