By Chris Bucholtz

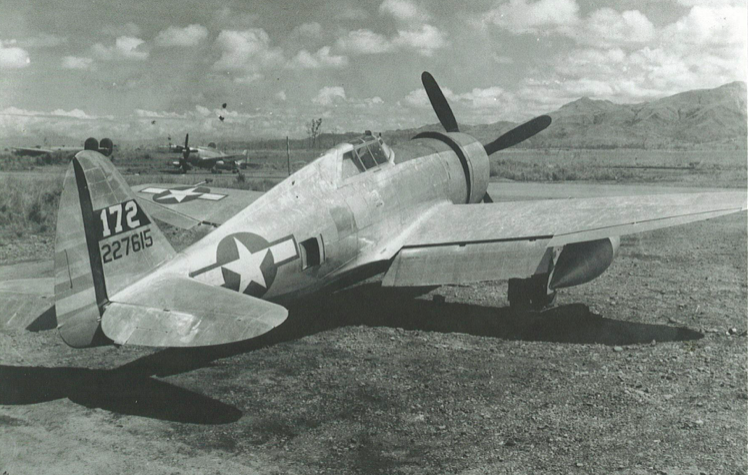

In the early morning of November 20, 1944, Lt. Cliff Saari and his fellow P-47 Thunderbolt pilots were hunting for more trouble. That morning, the eight P-47Ds from the 378th Fighter Squadron, 362nd Fighter Group had already skipped bombs into the opening of a rail tunnel at Oberstein, destroying 20 rail cars and two locomotives on the nearby rail lines, before heading south to find more targets. Northeast of Saarguemünd, the flight leader spotted nine trucks on the road and ordered Saari’s flight down to attack. Saari checked to make sure his eight .50-caliber machine guns were charged and that his gunsight was on, and he banked into the attack.

He never saw what hit him. Just as he started firing, a small-caliber flak shell smashed into the right side of Saari’s engine cowling. Saari immediately pulled up and took stock of his situation — the engine was still running, although the plane had developed a disconcerting vibration and a chunk of the cowling was flapping in the slipstream. Worse, the R-2800 engine was spraying oil back onto the windshield, making it impossible to see forward. While the second flight destroyed the remaining trucks, Saari’s wingman gave Saari a worried assessment of the damage and navigated him back to their base at Etain, France — 125 miles to the west. Saari had no forward visibility, and flew on instruments for the 50-minute flight home. On the landing approach, Saari, tightened the strap on his goggles, opened the cockpit, and stuck his head into the slipstream to see the runway, setting the Thunderbolt down safely and rolling to a stop. The ground crew gasped at the sight of the plane — the fuselage and inner wings were completely covered in a thin, dripping layer of oil. Saari climbed out, then slipped and slid off the wing, landing on the ground in a heap — but safely home. Saari completed 80 missions in the Thunderbolt, and like many other pilots, attributed his survival to the ruggedness of Republic’s groundbreaking fighter.

But ruggedness wasn’t the P-47’s only impressive quality. The eight .50-caliber machine guns were devastating; some pilots reported the impact of their massed bullets knocked rail cars off the tracks. The plane’s ability to dive was unmatched. And it’s speed was nothing to sneer at — 426mph at 30,000 feet, thanks to the combination of the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 engine and a turbocharger housed in the belly of the aircraft. The most impressive testament to its value as a weapon is the sheer quantity of Thunderbolts built — 15,683, of which 12,602 were P-47Ds.

The Thunderbolt’s heritage stemmed from two earlier designs from Alexander Kartveli, the chief designer for Seversky Aircraft Corporation. In 1937, the company introduced the P-35, the first U.S. Army Air Corps fighter with all-metal construction, retractable landing gear and an enclosed cockpit. It also boasted an elliptical wing plan and a radial engine, features carried over to the renamed Republic Aviation Company’s P-43 Lancer, which was slightly larger and significantly faster than the P-35, and which boosted performance with a belly-mounted turbo-supercharger — another trait the P-47 would inherit. The P-43 made its debut in 1939, but by then the Curtiss Hawk series had found favor with the Air Corps as the standard U.S. fighter. About half of the 272 P-43s were converted for photo reconnaissance; 180 fighter and photo variants were given to the Chinese Nationalist forces.

Absorbing information from European combat reports and from American research into aerodynamics and engines, in 1940 Kartveli proposed a new fighter, one which was probably the most sophisticated single-engine fighter in the world at the time, and certainly the largest. Kartveli designed the powerplant and turbocharger arrangement first, then planned the rest of the aircraft around it, using lines similar to his two previous designs. The engine, the then-new Pratt & Whitney R-2800, sent exhaust gasses through two enormous ducts to the turbocharger in the plane’s belly; depending on the altitude, the gasses were either vented through a waste gate or used to drive a 60,000 RPM turbine that fed high-pressure air into the engine for improved high-altitude performance. Intercoolers made the air denser, further boosting engine output.

The maze of ducts, vents and turbines mandated a large, deep fuselage, but putting this at the bottom of the aircraft forced Kartveli to move the wing slightly higher on the fuselage. This made the P-47 even heavier, since it meant the plane’s landing gear had to be longer to accommodate the massive propeller, with an accompanying weight penalty. Seversky also insisted on the eight-gun armament, as well as self-sealing fuel tanks, and a cockpit with more complete instrumentation than other types.

The result was a very big aircraft, especially compared to its peers at the time. The Spitfire Mk. I had an unloaded weight of 4,306 pounds, the Bf 109E tipped the scales at 4,522 pounds, and the P-40B weighed 5,590 pounds. The P-47 weighed an incredible 9,950 pounds unloaded; maximum take-off weight for missions was 17,500 pounds. It was nine feet longer than the P-40, and three feet greater in span. The final result was a fast, intimidating machine that could absorb — and dish out — enormous punishment.

It was also a plane that continued to evolve. As first designed, the plane had a sharp upper line to the top of the fuselage from the cockpit to the tail, resulting in the “razorback” nickname. The arrangement limited visibility, so Republic cut down and redesigned the rear fuselage and fitted a blown canopy to P-47Ds starting with the P-47D-25-RE (25 being the production block number, and RE for its manufacture at Republic’s Farmingdale, New York plant). The “bubbletop” was less laterally stable than the “razorback,” so starting with the P-47D-27-RE a shallow fillet was added ahead of the vertical tail. The P-47D-30 added compressibility flaps below the wing, and the P-47D-35 came with zero-length rocket launchers.

In the summer of 1944, as V-1 attacks on England increased, Republic produced the hot-rod P-47M model. This boasted an upgraded engine and turbocharger system which allowed it to reach 504 miles per hour. But all of the lessons learned in combat were rolled into the redesigned P-47N, a long-range version that featured a new, longer-span wing with integral fuel storage, enlarged ailerons, a larger tail fillet, beefed-up landing gear and an upgraded engine. The improvements turned the previously short-legged Thunderbolt, which could carry just 305 gallons of fuel, into 1200-gallon lugging monster ideal for long-range work in the Pacific, which it performed ably in the last six months of the war.

When the Thunderbolt went into action in Europe in March 1943 with the Fourth Fighter Group, opinions of the plane — dubbed “the Jug,” a shortened form of “juggernaut,” which also effectively described its fuselage shape — were decidedly mixed. A recurring joke held that, if a pilot found himself in trouble in the P-47, he could unbuckle his harness and run around the spacious cockpit until he found shelter. The Fourth had been flying nimble Spitfires, and some, including 335th Fighter Squadron commander Don Blakeslee, detested the new machine. Fellow ace James Goodson checked Blakeslee out on the P-47. “Of course he didn’t like it,” said Goodson. “It was daunting to haul seven tons of plane around the sky after the finger-tip touch needed for the Spitfire.” When Blakeslee scored the group’s first victory in the P-47 by catching an Fw 190 over Ostend as it raced for the deck, Goodson exclaimed “I told you the ‘Jug’ could out-dive them!” Blakeslee shot back, “It damn well ought to be able to dive — it sure as hell can’t climb!” (a succession of improved propellers later gave the P-47 a much improved climb rate.) In other pilots, the plane inspired confidence. “It was a real powerhouse,” said Harold Comstock of the 56th Fighter Group. “I was never afraid of it. It handled very well in the air, and the performance at high altitude was most impressive. I was just happy to know I was going to combat in the P-47”

It wasn’t just Blakeslee and the Fourth Fighter Group who began scoring in the P-47. The 56th and 78th Fighter Groups began operations in April 1943, escorting daylight bombing missions and flying fighter sweeps into occupied Europe. They were joined by the 355th Fighter Group in July 1943, the 353rd FG in August, the 352nd FG in September, the 356th FG in October, the 359th FG in December and 361st FG in January, 1944.

The P-47 was a classic energy fighter; with an altitude and speed advantage, it was extremely dangerous. The favorite approach was a diving attack, followed by a pull-out and return to altitude for another pass — the familiar “boom and zoom” attack. Its arrival was disconcerting to Luftwaffe pilots, who had become accustomed combatting the Spitfire and using the energy tactics the Thunderbolts were now employing against them — only with greater firepower.

For example, in January 1944, Lt. Glen Schlitz of the 63rd Fighter Squadron, 56th Fighter group scored three, leading his flight against a gaggle of about 20 Bf 109s. “They were flying tight, but I got in and shot the leader off first,” he reported. “He nosed over. I gave him a burst in the belly tank, and he blew up like a firecracker. The fool who was flying his wing just sat there watching, so I gave him a few bursts too, and he blew up.” When the Bf 109s split up, Schlitz saw another Bf 109 attacking a B-17, dove on it and again exploded his opponent in flight. “I guess good old caliber .50s affect them all the same way,” Schlitz mused.

These early P-47s displayed the type’s major drawback — short range. The P-47Cs and early P-47Ds in combat in the spring of 1943 had no ability to carry external fuel, so they only managed about two hours of flying time. That put them in range of the northern coastal areas of France, Holland and Belgium. Improvements to fuel capacity stretched the P-47s range, from a combat radius of 125 miles to 230 miles with the addition of 75-gallon belly tanks in August 1943, then to 275 miles with the 108-gallon impregnated paper tanks in September 1943. By April 1944, the addition of wing pylons plumbed for fuel allowed Thunderbolts a maximum combat radius of 425 miles — better, but still short of major German target cities like Leipzig, Stuttgart and Berlin. On deep penetration raids by the Eighth Air Force, the Luftwaffe began holding its fighters back until the P-47 escort was forced to turn for home, then throwing the full weight of their fighter force at the bombers. The catastrophic raid on Schweinfurt and Regensburg on August 17, 1943 showed that the Eighth Air Force’s bombers needed escorts to achieve their mission — and the P-47 was not going to be that aircraft. With the arrival of the longer-legged P-51 Mustang in December 1943, the Eighth Air Force began transferring its Thunderbolts to the Ninth Air Force. By the end of 1944, the Eighth Air Force was an all-Mustang outfit, except for the 56th Fighter Group, which retained its Thunderbolts until the end of the war.

The Ninth Air Force was the tactical arm of American air power in Europe. After its initial service in North Africa, the command was transferred to England and rebuilt to support the invasion of France. Upon its return to England, its first new fighter group, the 354th, was equipped with Mustangs. One unlucky pilot, the Fourth Fighter Group’s Vernon Boehle, wanted out of Thunderbolts and, upon seeing the 354th’s Mustangs, asked for a transfer — just as it was decided that the Ninth Air Force would be a primarily Thunderbolt fighter force. Boehle ended up in the 362nd Fighter Group, flying Thunderbolts until the war’s end!

The P-47, designed for combat at high altitude, would fly as a low-level fighter-bomber, a role it excelled in. With its firepower and survivability, it had a much better chance of bringing its pilots home than the Mustang, and operating near the front lines minimized the impact of its limited range. Starting in January of 1944, Ninth Air Force P-47s flew escort missions like their Eighth Air Force counterparts, but gradually they began to specialize in interdiction and ground attack roles as IX and XIX Fighter Commands built strength in advance of D-Day. At their peak, the Ninth Air Force operated 13 P-47 groups.

As D-Day approached, the P-47s spread a swath of destruction behind the coastal areas of France and Holland, hitting targets across the entire area to avoid tipping off the Germans to the chosen landing sites. Airfields, V-1 sites, gun emplacements, and especially railroad targets were the main areas of focus. Attacking rail lines was straightforward, but attacking moving trains took some technique, according to Capt. Jim Ashford of the 379th Fighter Squadron, 362nd Fighter Group. “You want to be fairly low so your angle of dive on the train is quite low,” he said. “You don’t want to come down at a 45-degree angle because that means you have to start pulling out earlier so you don’t smash into the train, and you have less time to shoot. We inevitably took more of them from the side rather than going right down the track.”

The toughness of the P-47 gave pilots the confidence to press their attacks, and sometimes they could press their luck, too. On May 28, 1944, the 365th Fighter Group attacked a railroad bridge at Hasselt, Belgium with 68 1000-pound bombs — and the bridge still stood. Lt. Neal Worley made a pass to inspect the damage, “when here was a German troop train,” he told historian Don Barnes. “I made a high-speed pass on a train loaded with artillery and crew, and a whole battalion came up out of the railroad cars and headed for foxholes.” Worley made a second pass, aiming at the locomotive, but as he flew past the locomotive a water tower supported by half-inch steel cables flashed past. “I made a sieve of the locomotive, but I ran into the steel cable, wrapping about 40 feet of it around the prop,” he said. “The cable partially unwound and a big strand of it started hitting the canopy. Worse, the Thunderbolt wouldn’t fly over 100 mph. It would roll on it back if its speed dropped much. With a broken antenna, that wire started snapping like a whip, extending 10 feet beyond my plane’s tail.”

He flew out of France and across the channel at low altitude, but he knew his fuel was about to run out. “I chose to belly into the ground and a hedge fence at 125 mph. I remember turning my head sideways just as I hit the ground, and the plane went to the right. Up ahead, with my speed down to about 100 mph, there was a big concrete abutment. I hit a mound of earth that threw me up over the concrete. My head hit the gunsight and I was seeing stars as big as cups and saucers. I shook my head and heard this ‘clump, clump, clump’ on my wing. It was an Englishman who said, ‘I say there, old chap! You’re in a bit of a spot!'”

As the Allies bogged down in bocage country, the Thunderbolt became an invaluable tool for paralyzing German forces and denying them re-supply. The German forces cut off on the Crozon Peninsula were subjected to relentless P-47 attacks between August 15 and September 19 that led directly to the German garrisons’ surrender in Brest and Crozon. Pivoting to the east, Ninth Air Force units struck marshaling yards, bridges, rail tunnels, gun emplacements and troop concentrations, with the 13 groups leapfrogging bases to keep pace with the ground troops.

As winter of 1944 set in, the P-47s were crucial in keeping the Germans off balance. The men who maintained them worked miracles servicing the aircraft in the freezing weather — few of the Ninth Air Force’s fields had hangars to work in. Weather could also keep P-47s on the ground, and make it hard for Thunderbolts to safely return to earth. On a freezing January 22, 1944, the 362nd Fighter Group caught the Sixth SS Panzer Armee embarking on trains for transport to the Eastern Front and flew into ferocious flak, ranging from 88mm guns to small arms fire, costing them five P-47s and four pilots. Ray Murphy’s Jug, Chief Seattle, was hit by two 40mm and one 20mm shell, which blew out a tire, fractured the hydraulic system and knocked two cylinders off the engine. “I managed to keep my crippled plane in the air for the 75-mile flight home,” he said. “The airstrip was covered in ice and as I touched down, seven tons of Thunderbolt on a blown tire veered off the runway, plowing into a snow-covered field. I cut the switch to prevent fire and climbed out without a scratch!” Not only did Chief Seattle save Murphy, but it also returned to combat, only to be lost on April 18, 1945, in a takeoff accident. Although Republic produced over 15,000 P-47s, there were never enough of them, so planes that were severely damaged — including many that were scavenged for parts by their original units and were mere shells — went through depot overhaul and returned to dish out more punishment.

In the Mediterranean Theatre, the fighter groups of the 12th and 15th Air Forces followed a similar pattern to that of the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces in England. The 325th Fighter Group was the sole P-47 group in the 15th Air Force, inherited from the 12th Air Force when it re-organized to focus on tactical missions while the 15th concentrated on strategic missions. The “Checkertail Clan’s” veteran planes went to depot for overhaul, and were distributed to other 12th Air Force units in the Theater, most notably, the 332nd Fighter Group, which traded in its P-39s for Thunderbolts for a short 30-day stint. When the 332nd and 335th FGs were transferred to the 15th Air Force for escort duties in the P-51, their Thunderbolts, in turn, were distributed to other 12th Air Force Units — the 27th, 57th, 79th, 86th, 324th and 350th Fighter Groups — who used them to replace their A-36s, P-39s or P-40s, flying them in combat over Italy, providing close air support during a difficult campaign. Additionally, the Brazilian 1st Fighter Aviation group flew in Italy in conjunction with the 1st Liaison and Observation Squadron in a seven-month campaign, earning commendations for its work.

The P-47 also saw action in the Pacific, although the short range of the P-47D kept it from earning a spot as one of the premiere fighters in the campaign against Japan. Eleven fighter groups in the Fifth Air Force had at least one squadron of P-47s in February 1944, but the 348th FG was the unit that showed how effectively the Thunderbolt could be used against Japanese fighters. From June 1943 to April 1945 the 348th flew every type of mission that Fifth Air Force command could conceive of, thanks in part to Fifth Air Force commander’s order to the 27th Depot Repair Squadron at Port Moresby, New Guinea to design a suitable tank for the theatre. The result was the “Brisbane tank,” a 200-gallon belly tank that dramatically extended the plane’s range. It also didn’t hurt that the group’s commander, Neel Kearby, was an ardent defender of the P-47, and he backed up his words with actions: On October 11, 1943, Kearby shot down six planes and his four-ship flight downed nine in total on a sweep over the Japanese base at Wewak, an action for which he earned the Medal of Honor. The beloved Kearby wrote the book on using the Thunderbolt in the Pacific against the nimble but fragile Japanese fighters: achieve an altitude advantage, dive, and get close before opening fire, then climb for another pass. Kearby racked up 21 victories by March, 1944, in pursuit of Eddie Rickenbacker’s 26 and in competition with Richard Bong and other emerging P-38 aces.

Sadly, on March 5, Kearby broke his own rules, and paid for it. Over Dagua, on the north coast of New Guinea, he and his wingmen spotted three Ki-48 bombers descending to land at the airfield there. Kearby damaged one of them, and his second element leader bagged another one. But as the three other Thunderbolts zoomed for altitude, Kearby made a 360-degree turn to hit his bomber again, bleeding off speed. He downed the Ki-48 — only to fall victim to a Ki-43 Hayabusa fighter that had been unseen to that point. Kearby’s canopy flew off, and he bailed out of the aircraft; wingman Bill Dunham caught the Ki-43 and sent it down in flames. But it was too late for the 348th’s leader; Kearby had been fatally wounded. His body was recovered in 1948, not far from where his parachute had caught in a tree.

The P-47D served ably as the U.S. Army worked its way up from New Guinea into the Netherlands East Indies and ultimately the Philippines, but its days were numbered. Competitors with better range — both the Mustang and the P-38 Lightning — once again spelled an end to the P-47D’s bid at being the top dog by the spring of 1944. But a new Thunderbolt was on its way; the P-47N was introduced to combat in April 1945 with the 413 and 507th Fighter Groups, and the 414th FG arriving in theatre in time to fly a few missions. The long-legged, rocket-armed P-47Ns flew as part of the 20th Air Force, ranging over Korea, China, and Japan’s home islands, shooting up anything perceived to be of military value. Lt. Oscar Perdomo became the war’s last “ace in a day” when he shot down four Ki-84s and a Yokosuka K5Y trainer near Seoul, Korea on August 13, 1945, a feat matched by Lt. Richard Anderson of the 318th FG, who had destroyed five Zeros over Kyushu on May 28, 1945.

The war’s end brought the Thunderbolt’s combat career to an end, but the nearly 2,000 P-47Ns manufactured (and a large contingent of P-47Ds) helped flesh out the post-war Air National Guard and the Air Force, which flew them until the mid-1950s. Big, reliable, survivable, adaptable, and packing an enormous punch: the P-47 created the template for all the fighters that followed it.

The photo of a Razorback Jug in bare metal with prewar red, white, and blue rudder stripes is from either the 35th, or 348th Fighter Group. The never was a “386th Fighter Group”,_but, there was a 386th Bomb Group, however. Also, the P-47M has a top speed of 478mph, but, some Crew Chiefs from the 56th Fighter Group found a way to squeeze some more power from the engine, allowing the P-47M to top out at 502mph.