For nearly 70 years now, the Planes of Fame Air Museum of Chino, California has been viewed as a hub for warbirds kept in airworthy condition, flying everything from the last flying Boeing P-26 Peashooter (see our article on that aircraft HERE) to the only Mitsubishi A6M Zero to fly with its original Nakajima Sakae engine (see this article HERE). The museum even flies several Korean War-era jet fighters, such as the only single-seater of the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 flying in the United States (see this article HERE), but in the museum’s Jet and Air Racers Hangar, visitors will also find an array of air racers, and standing tall among the small Midget/Formula One air racers that flew at the Reno Air Races are reminders of a time when the fastest air racers were seaplanes that competed in the Schneider Trophy Race, held from 1913 to 1931. Yet the story of how the Planes of Fame got these racers is just as fascinating as the stories they were built to represent.

In order to understand the significance of these replicas and why seaplane racers attracted so much attention in the first place, we must travel over 100 years to the very beginning of the airplane. In 1908, Wilbur Wright took an airplane that he and his brother Orville constructed to Le Mans, France. Despite the initial skepticism over the claims that two brothers who owned a bicycle shop in Dayton, Ohio, had done what had been considered impossible for millennia, Wilbur’s subsequent demonstrations before the European aviation community proved the feasibility of the airplane. They induced a rush of aspiring young men and women around the world to turn to the skies above.

Among those who came to see Wilbur Wright at Le Mans was a French industrialist, balloonist, and aircraft and racing enthusiast named Jacques Schneider. While his family had gained their fortune through the Schneider-Creusot iron and steel works, which also made arms for the French military, Schneider could see the future of flight, even as the airplanes of his time were underpowered and fragile machines crafted by hand. When Schneider was severely injured in a hydroplane boating accident in 1910, his flying career came to an abrupt end. Though his body was broken, his fortune was intact, and he was determined to remain a benefactor for the burgeoning aviation community.

In 1912, Jacques Schneider served as a referee at the first seaplane meet, which was held in Monaco. Fellow Frenchman Henri Fabre had built and flown the first successful seaplane, the Fabre Hydroavion, in 1910, and by 1912, a number of European and American aviators had built their own seaplanes, with some standing on the water with pontoon floats, and others constructed as flying boats. At Monaco, Schneider was certain that the future of air travel and commerce lay with seaplanes. With so much of the earth’s surface consisting of water and concerned with the lack of dedicated flying fields for land-based airplanes, Schneider believed that seaplanes would become more reliable, have longer ranges, and carry greater payloads than their land-based cousins in the air.

On December 5, 1912, at a meeting and banquet of the Aéro-Club de France in Paris, Jacques Schneider announced the creation of the Schneider Trophy for seaplane races. Among the rules for the trophy was that if any nation won three consecutive races, they would become the permanent custodians of a 25,000-franc trophy made of silver and marble showing the Spirit of Flight kissing the Spirit of the Waves, symbolizing the conquest of the sea and the air. Additionally, the winning pilot would receive 75,000 French francs.

The first of these is a representation of the Deperdussin Coupe Schneider, a floatplane development of the land-based Monocoque racer that became the first airplane to exceed 130 mph (210 km/h). Following the establishment of the Schneider Trophy, the first of the Schneider Trophy air races was held in Monaco on April 16, 1913. Just five airplanes would be entered into the race, all of them being pontoon-equipped versions of French racing aircraft. These were the Borel hydro-monoplane (race no. 4, based on the 1911 Morane-Borel monoplane), the Deperdussin Coupe Schneider (race no. 19), a Morane-Saulnier G (race no. 2), and two Nieuport IV.Hs (race nos. 5 and 6). During the race, the Borel crashed during the elimination trials, and the two Nieuports, flown by Haitian-born French-American Charles Weyman (no. 5) and Gabriel Espanet (no. 6), were forced to retire during the race, leaving only Maurice Prévost in Deperdussin (no. 19) and Roland Garros of future WWI and tennis fame in his Morane-Saulnier G (no. 2). In the end, Prévost won first place in the first Schneider Trophy race, coming in at an average speed of 45.71 mph. Despite the Deperdussin Coupe Schneider being able to travel up to 120 km/h (75 mph, 65 kn), Prévost had averaged a faster flying speed during the race, but he lost 50 minutes when he landed prematurely after losing count of the laps completed. This is also why Prévost came first despite Garros having a faster average of 92 km/h (57 mph). The aircraft had also been repaired following a hard landing on the water, which resulted in the tail breaking and hanging down from the fuselage. Later that same year, Prévost would also win the Gordon Bennett Trophy for landplanes at Reims, while Garros gained fame for becoming the first pilot to fly nonstop across the Mediterranean Sea, which was considered one of the great flights of the pre-WWI era.

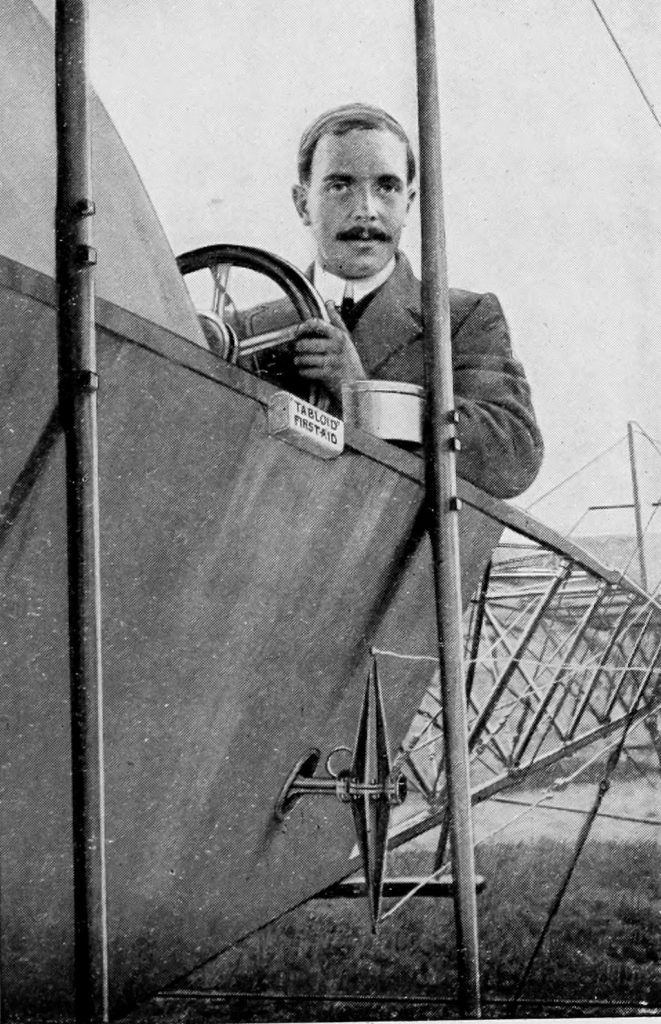

The 1914 races would also be held in April at Monaco, where British pilot Howard Pixton won the race in a Sopwith Tabloid biplane, achieving an average speed of 86.83 mph (139.74 km/h). This glory was to be short-lived, however, for less than three months later, on June 28, Austrian archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo, the event becoming the trigger point for World War I. From 1915 to 1918, the war prevented any further racing, which did not resume until 1919, and would be a staple of 1920s aviation.

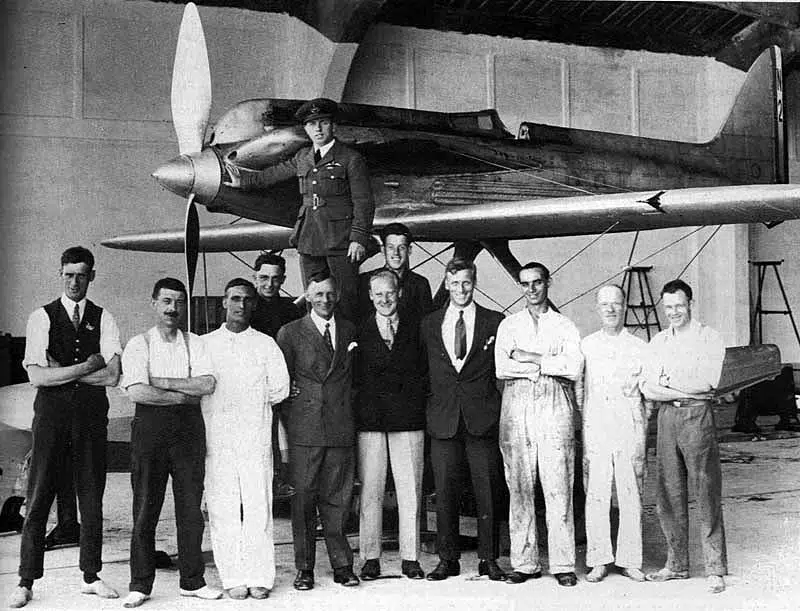

With the races taking on a sense of national pride for the competitors, aircraft and engine design advanced rapidly to stay ahead of the competition, while the races also served as venues for the world’s foremost body governing air sports, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), to certify new speed records. The races were eventually won by the British in 1931, with the Supermarine S.6B, designed by Reginald J. Mitchell and flown by Sir John Nelson Boothman, securing victory at an average speed of 340.08 mph (547.31 km/h). Mitchell would later use the expertise he learned in building Schneider Trophy races to the design of the Supermarine Spitfire, arguably the most influential British fighter aircraft in aviation history.

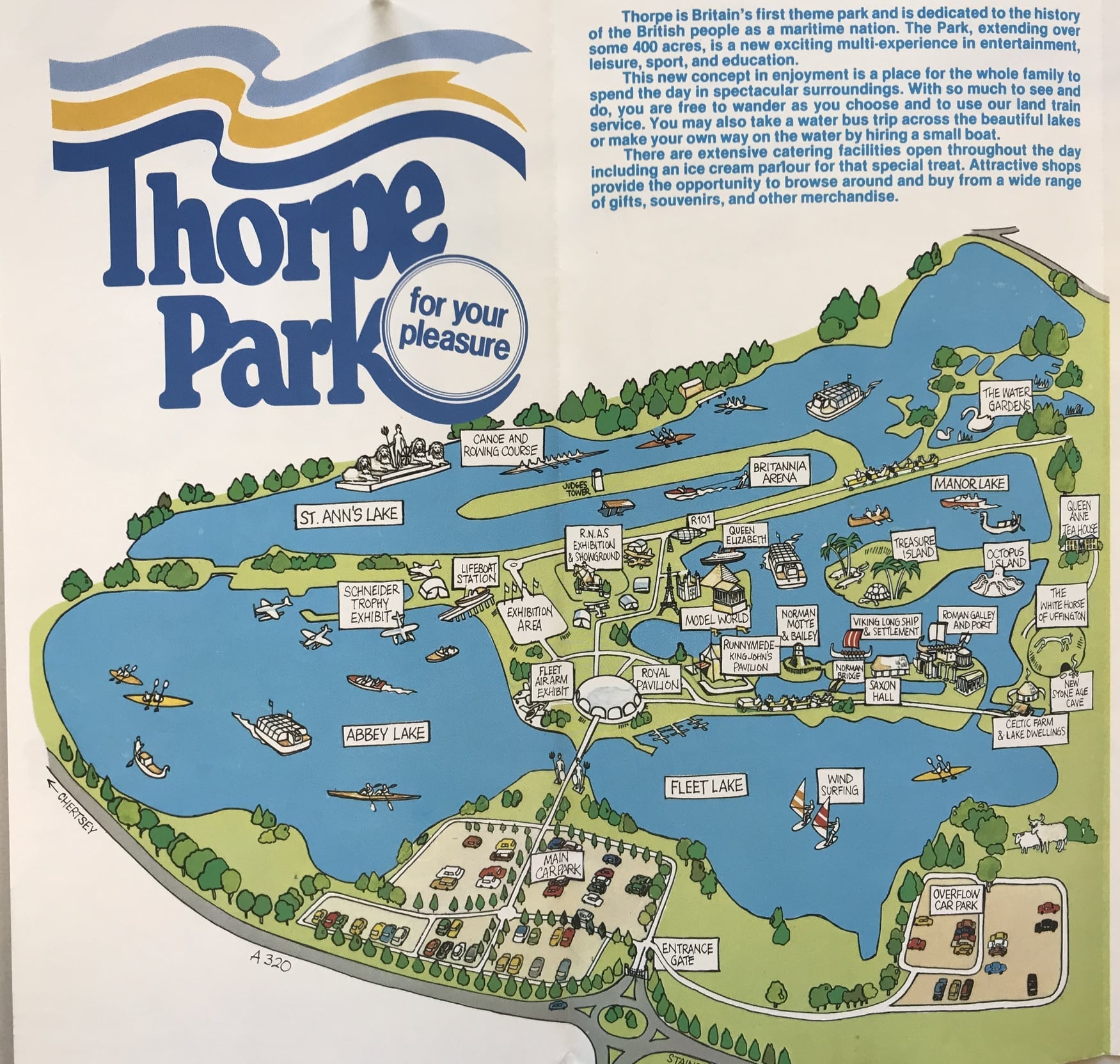

Nearly five decades after the final Schneider Trophy races, the Thorpe Park amusement park, located between the towns of Chertsey and Staines-upon-Thames in Surrey, England, opened on May 24, 1979, with Lord Louis Mountbatten attending the dedication just three months before his assassination by the Provisional Irish Republican Army. Among the attractions at Thorpe Park were several historical settings, from a Stone Age cave to a Roman port and Viking camp. But the park also featured displays of replicas of aircraft from the First World War and the Schneider Trophy Races. Some of these aircraft were built to airworthy standards and registered to the United Kingdom Civil Aviation Authority, while others were built as static replicas that would be displayed at the park. Of particular interest are four static replicas of Schneider Trophy racers that were displayed at Thorpe Park and have now found themselves across the Atlantic in the Planes of Fame Air Museum of Chino, California.

The first of these is a representation of the Deperdussin Coupe Schneider, a floatplane development of the land-based Monocoque racer that became the first airplane to exceed 130 mph (210 km/h). Like all of the static Schneider racer replicas (and much of the WWI fighter replicas) at Thorpe Park, the Deperdussin was constructed by Leisure Sports Ltd, which also gave these replicas serial numbers with the code BAPC. The Thorpe Park Deperdussin would become BAPC-136. The racers were also designed to float on the park’s artificial lake, where they could be seen on display.

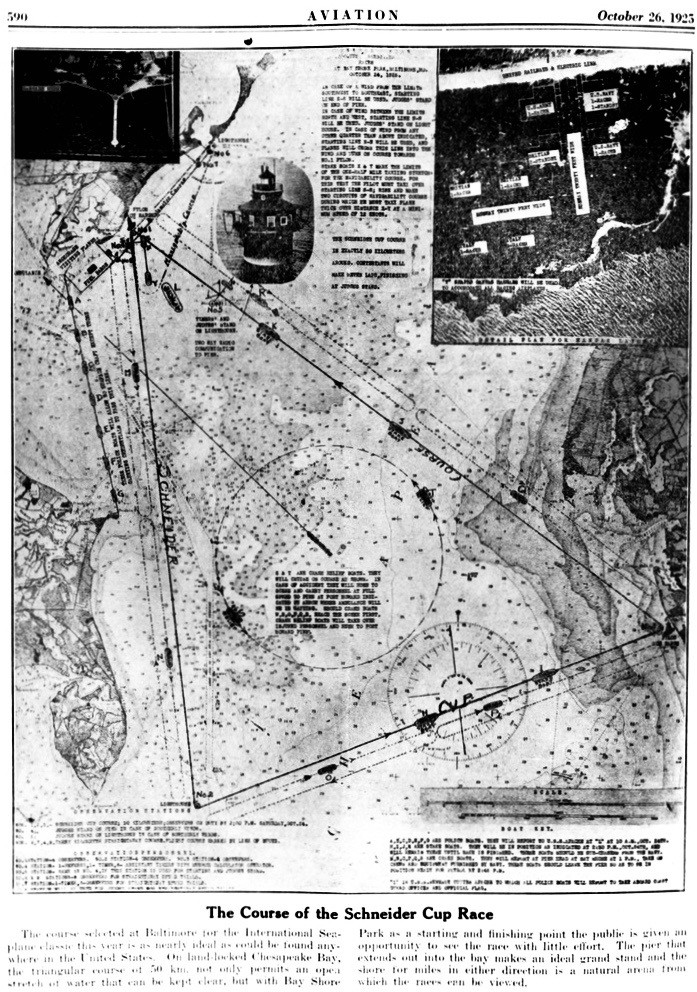

The next replica racer was constructed to represent the Curtiss R3C-2 (Leisure Sport number BAPC-140). In 1923, the Americans had won an upset victory against the British and the French at the English seaport of Cowes using the Curtiss CR-3 racer, powered by a 475 hp Curtiss D-12 engine. With the 1924 races cancelled due to a lack of aircraft ready to participate, it was up to the Americans to defend their stake on the Schneider Trophy in Baltimore. The French did not enter any aircraft into the competition, so it was up to the British and the Italians to wrestle the trophy back from the Americans. The 1925 race was held on a course over the Chesapeake Bay, just south of Baltimore. With the British and the Italians flying the Gloster IIIA, the Supermarine S.4, and the Macchi M.33, the Americans competed in a new racer developed from the CR-3, the R3C-2. Less than a month before the Schneider race, one of the R3C-2s in the roster, serial no. A7054, had just won the Pulitzer Trophy Race (the U.S. National Air Races) as race no. 43, with Army Lieutenant Cyrus Bettis at the controls.

With the Supermarine S.4 crashing before the race, and two of the R3C-2s and one of the M.33s being forced to retire during the race, it was left to three racers (one Curtiss R3C-2, one Gloster IIIA, and one Macchi M.33) Ultimately, the Americans took first place in the 1925 race at Baltimore, with none other than Lt. James “Jimmy” Doolittle being the winning pilot in R3C-2 A7054, race no. 3, the same aircraft Bettis had won the Pulitzer Races in. Doolittle’s average speed came in at 232.56 mph (374.27 km/h).

That R3C-2 would later compete in the 1926 races held at Hampton Roads, Virginia, as race number 6, and finished in second place in that race. Following its 1926 performance, A7054 was donated by the U.S. War Department to the Smithsonian Institution, where it is on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

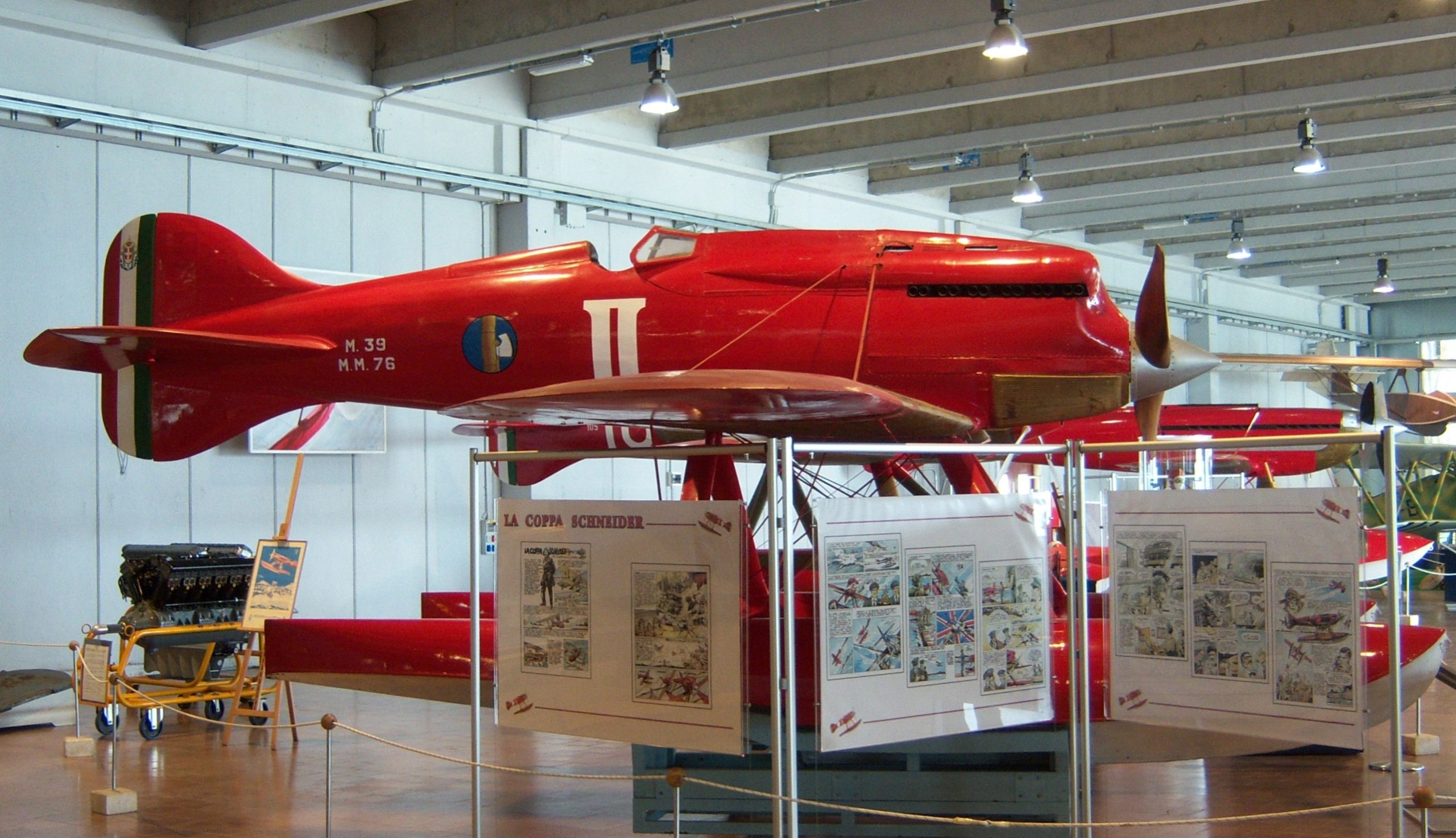

The third Schneider Trophy racer replica from Thorpe Park depicts the Macchi M.39 (BAPC-141). In the Italian aviation community, the Schneider Trophy Races represented the peak of modernity, speed, and horsepower. This point was also not lost on the newly appointed Prime Minister, Benito Mussolini, soon to style himself as Italy’s ‘Duce’ (leader) and fascism’s first dictator. Having been a newspaper editor, Mussolini knew a good story when he saw one, and charged the Regia Aeronautica to “win the Schneider Trophy at all costs”. In Varese, Aeronautica Macchi’s chief seaplane designer, Mario Castoldi, developed a new monoplane racer that was to become the Macchi M.39. Fitted with a Fiat AS.2 V-12 engine that 597 kW (801 hp), the M.39 was sent to Hampton Roads to wrest the Schneider from the Curtiss biplanes.

The R3C-2s that had been victorious in the 1925 race made a good showing, but this time, it was the Italians who won first place, with pilot Mario de Bernardi averaging 396.70 km/h (246.50 mph) in M.39 serial number M.M.76, while M.39 s/n M.M.74 came in third, and M.M.75 was forced to retire mid-race. 1926 would also be the last Schneider Trophy race to take place outside Europe. Today, Macchi M.39 s/n M.M.76 is on display at the Museo Storico dell’Aeronautica Militare (Historical Museum of the Italian Air Force) at Vigna di Valle.

The 1927 Schneider Races held in Venice would see the British come back in force, winning in the Supermarine S.5. After a year’s hiatus, the races in 1929 at Calshot, Hampshire, would see Supermarine again take first place, this time in the Supermarine S.6, powered by the Rolls-Royce R V-12 engine, which produced a stunning 1,900 hp (1,400 kW) at 2,900 rpm. The next races were expected to be held in 1931, but shortly after the 1929 race, the stock market crash on Wall Street sent the world into the Great Depression. Work ground to a halt, and in Britain, Parliament withdrew its support for further racing, as many did not see the point in spending public money on air racing while families struggled to find jobs to provide a living.

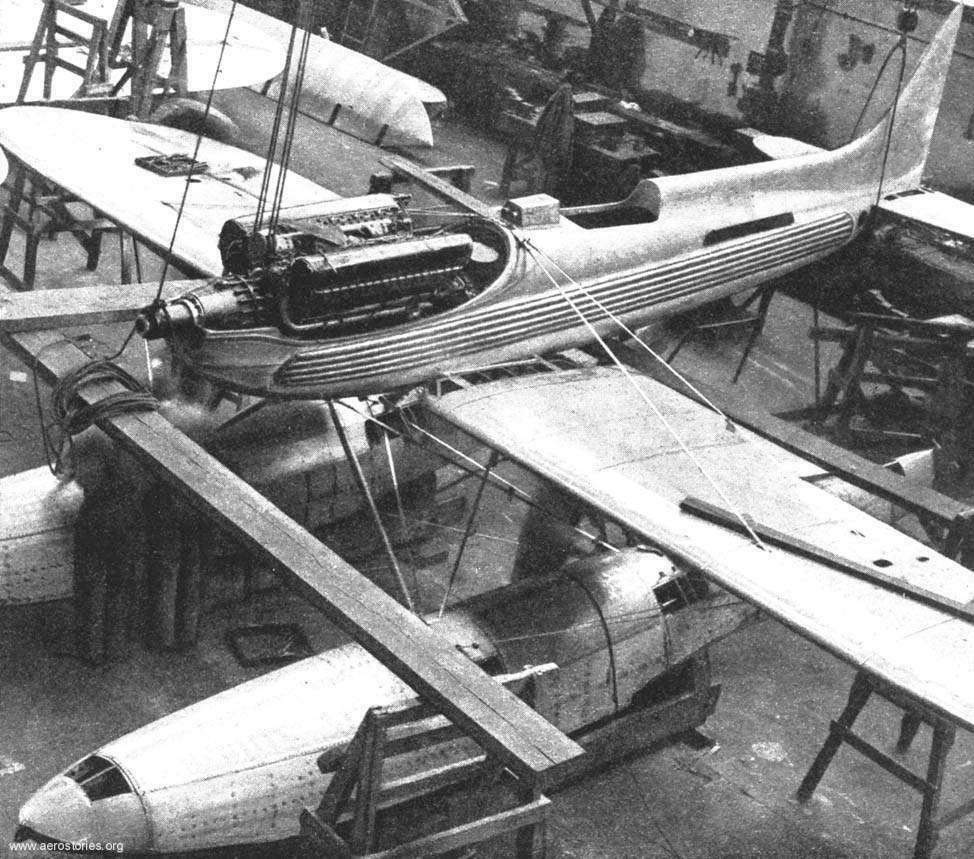

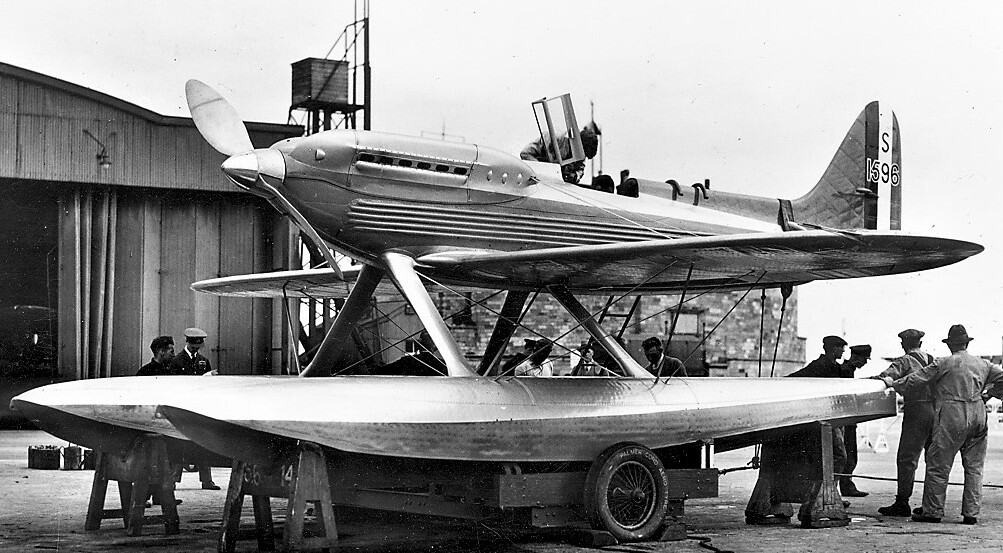

Yet with the French and the Italian governments deciding to back their entries for the 1931 races, the British aviation community wanted to secure the Schneider Trophy, as Britain needed only one race to keep the trophy permanently. With the financial backing of Lady Houston, who donated £100,000 to the project, and a fundraising/publicity campaign by the Daily Mail, the British Parliament renewed its support of the Royal Aero Club’s mission to win the trophy. However, the time and monetary constraints required a more conservative approach, so while the Italians hedged their bets on the Macchi M.C. 72, with two Fiat AS.5 V-12 engines coupled together to form the Fiat AS.6 engine, Reginald J. Mitchell, designer of the S.4, S.5, and S.6 racers would modify the existing S.6 into the S.6B, which featured an upgraded Rolls Royce R, a unique fuel mixture, better streamlining, and more radiators on the aircraft, including the floats, which led Mitchell to describe the aircraft as a “flying radiator”.

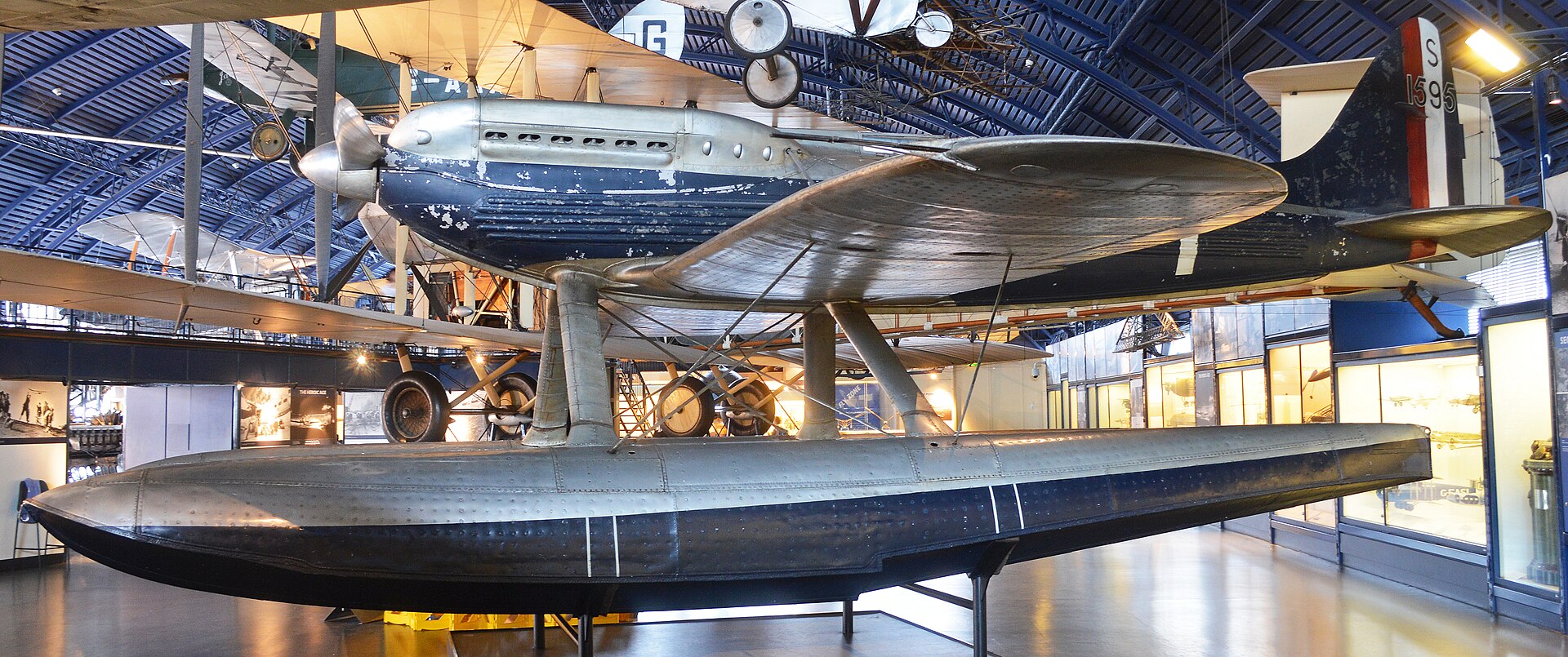

By the time the S.6B was sent to Calshot, both the French and the Italian teams had been forced to withdraw their entries, the Supermarine S.6B serial number S1595 (race no. 1), flown by John Boothman flew the prescribed course at an average speed of 547.31 km/h (340.08 mph). After the Schneider Trophy race was finished, George Stainforth took off in S.6B s/n S1596, and set a new speed record of 407.5 mph (655.67 km/h), marking the first time an aircraft exceeded 400 mph. Since 1931, the Schneider-winning S.6B S1595 has been on display along with the Schneider Trophy at the Science Museum in London, and a replica of S1595 was also built for Thorpe Park, which was given the Leisure Sport code BAPC-156.

Besides the static replicas of the Deperdussin, Curtiss, Macchi, and S.6B racers, Thorpe Park was also home to an airworthy replica of Supermarine S.5, RAF serial number N220, the winner of the 1927 races held in Venice, Italy, a replica of a Vickers Viking amphibious flying boat, and numerous airworthy and static replicas of WWI fighter aircraft. The WWI aircraft consisted of two Airco DH.2s, one Albatros D.Va, one Bristol M.1C, two Fokker Dr.I triplanes, three Fokker D.VIIs, one Hansa-Brandenburg W.29 two-seat floatplane, two Sopwith Camels, one Sopwith 1 ½ Strutter, one Sopwith Triplane, one Sopwith Baby, and one Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a. Many of these depicted the aircraft flown by famous aces of the First World War, such as Manfred von Richthofen, Arthur Roy Brown (the Canadian ace officially credited by the RAF of shooting down von Richthofen), Raymond Collishaw, Hermann Göring, Ernst Udet, and others. A peek into some of the aircraft can be seen 5 minutes and 34 seconds into this video uploaded to YouTube: Thorpe Park in the Early 1980s

However, this begs the question: how did the Thorpe Park air racers get from Surrey to Chino. The answer lies when Thorpe Park re-evaluated the space the exhibits occupied and decided it would be better instead for them to remove the WWI aerodrome in place of new rides and attractions for a younger audience. By the mid to late 1980s, the aircraft were sold off, with the WWI replicas being the first pick for many collectors. However, the founder of the Planes of Fame Air Museum, Edward T. Maloney, would show an interest in the static Schneider racers.

Although the Planes of Fame Air Museum has been primarily focused on maintaining WWII fighters, bombers, and training aircraft in airworthy condition, Maloney also fondly remembered following the exploits of the air racing pilots of the 1920s and 1930s, when tens of thousands of people turned out to watch the fastest aircraft of the day compete for trophies such as the Bendix and the Thompson. As a boy growing up in 1930s California, Ed built balsa wood models and collected photographs and newspaper clippings of these aircraft. Additionally, the Planes of Fame was highly involved in the National Championship Air Races held at Reno-Stead Airport, Nevada, with Ed Maloney’s son Johnny, son-in-law Steve Hinton and other pilots for the museum racing both stock aircraft and creating dedicated racers, from the RB-51 “Red Baron” to the “Super Corsair”. With the four static Schneider Trophy racer replicas now for sale in England, Maloney purchased the Deperdussin, the Curtiss R3C-2, the Macchi M.39, and the Supermarine S.6B, intending these and other aircraft to be displayed in a new museum in Reno, dedicated to air racing.

This was to become the National Air Race Musuem, which was developed by Ed Maloney alongside Larry Collins, Jack Northart, and Cliff Purdy, who were all regulars of the Reno Air Races. They came up with the idea in 1989, began work in 1991 on converting a former warehouse in Reno into the museum, and on May 22, 1993, the National Air Race Museum was officially opened. In addition to the four replicas from Thorpe Park, there were other aircraft on display, many of which came from the Planes of Fame’s inventory, such as a Curtiss Model D “Headless Pusher” replica, the Rider R-4 “Firecracker” racer, Rider R-6 “Eightball” racer, and Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-10/U4 Werknummer 611943. A glimpse of this museum can be found in this YouTube video here: National Air Race Museum Reno. Sep 1994.

However, the National Air Race Museum proved to be a short-lived one, closing its doors less than two years after opening. With the closure of the NARM, Planes of Fame took the Schneider Trophy Racers back to Chino, and leased a hangar originally built during WWII when the airport was called Cal Aero Field to house them and several other aircraft in the museum until it raised enough funds to construct a new hangar now called the Jet and Air Racers Hangar. The Planes of Fame installed the Deperdussin, Curtiss R3C-2, and Macchi M.39 racers in this new hangar, alongside many of the Midget/Formula One racers formerly displayed at the National Air Race Museum, including the Hanson WH-1 ‘Sump’n Else’ and LeVier ‘Miss Cosmic Wind’ racer.

Due to lack of display space, though, the Supermarine S.6B replica was placed in storage away from public access but has recently been pulled out of storage and has been temporarily placed on display while disassembled in the museum’s USS Enterprise Hangar. The museum may still put the aircraft back in storage, but for the time being, the S.6B replica serves as a unique contrast against the museum’s Douglas SBD-5 Dauntless dive bomber and General Motors-built TBM-3E Avenger torpedo bomber. As an aside, the Supermarine S.6B was also once loaned to the old location of the Museum of Flying in Santa Monica, in a building on the north side of Santa Monica Airport. Since 2012, this museum has been on the airport’s south side, while the old museum building is now home to Atlantic Aviation SMO.

The Schneider Trophy racers would also have an outsized impact on military aircraft of the Second World War, with R. J. Mitchell’s experience with the Supermarine racers directly applying to his last project before his death from cancer in 1937: the Supermarine Spitfire, which arguably became the most iconic British fighter of WWII that went on to serve in nearly every theater of operations involving British Commonwealth forces, and which would continue to serve well into the 1950s. Meanwhile, the Rolls-Royce R engine used in the Supermarine S.6B would also be used in land speed record cars and speedboats and would provide experience that Rolls-Royce would use in developing the Merlin and Griffon V12 engines of WWII fame.

In Italy, designer Mario Castoldi, who was responsible for the Macchi M.39, would design other Schneider Trophy racers, culminating in the M.C. 72, which was to face off against the Supermarine S.6B in 1931, but was unable to make it to England. Instead, the M.C.72, complete with contra-rotating propellers and two Fiat AS.5 V12 engines coupled together to create the Fiat AS.6 24-cylinder engine, would break the speed record set by the S.6B, when on October 23, 1934, test pilot Francesco Agello brought the aircraft to an average speed of 709.207 km/h (440.681 mph). To this day, the M.C.72 remains the fastest piston engine seaplane to have ever flown, and Castoldi would later design fighters for Italy’s royal air force, the Regia Aeronautica, that would see combat during WWII, such as the C.200 Saetta (Lightning), C.202 Folgore (Thunderbolt), and C.205 Veltro (Greyhound). Leading up to the Italian Air Force centenary in 2023, the recreation of the Macchi-Castoldi M.C. 72 seaplane racer took shape in Desenzano del Garda on the shores of Lake Garda. HERE is our article.

While many visitors come to Planes of Fame for the collection of airworthy WWII aircraft, the four Schneider Trophy racers represent a time when air racing entered international consciousness, and when the seaplane racer was the fastest type of airplane in the world. Remembering these racers also highlights the impact of the racers on aeronautical engineering used for both civilian and military purposes, long after the last of these races came to an end. To support the Planes of Fame Air Museum, click HERE.