(Image Credit: B24HotStuff)

On a recent post here at Warbirds News, we reported on the anniversary of milestones in the history of what is perhaps one of the most famous bombers of all time, the Boeing B-17F Flying Fortress, Memphis Belle. In the article comments, we were contacted by Air Force veteran Jim Lux who stated “The first heavy bomber in the 8th Air Force to complete 25 mission in World War II was the B-24 Liberator Hot Stuff. It completed its 25th mission on February 7, 1943, three and a half months before the B-17 Memphis Belle.”

(Image Credit: USAAF)

While the article on Memphis Belle had included the qualifier “first B-17 United States Army Air Force heavy bomber to complete 25 combat missions with her crew intact,” which on a factual basis at least made the article “correct” insofar as it specified that it was the “first to 25 missions with her crew intact,” but the truth is, while we’re reasonably knowledgable about WWII lore here, the name “Hot Stuff” didn’t spark any particular recollection in us or among the several other warbird enthusiasts we asked about it, though one fellow we spoke to did remember it as the plane General Andrews lost his life in, but generally there wasn’t much recognition. That in mind, we’d like to try set the record straight, though the waters in this case are especially muddy.

(Image Credit: USAAF)

In 1942, during the first three months of America’s combat flights over Europe the average bomber crew was expected to complete 8-12 missions before being shot down or disabled. This in mind, the US Army Air Force decided that 25 missions while serving in a heavy bomber of the 8th Army Air Force would constitute a “completed tour of duty” because of the “physical and mental strain on the crew.” While the 25 Mission edict was a tall order when it was made, it was a number crews could believe in, and provided some hope of a light at the end of the tunnel, particularly necessary with the grim statistics bomber crews faced early-on, before long-range fighter escorts significantly improved mission survivability when they arrived later on in the course of the conflict.

(Image Credit: USAAF)

The 25-mission milestone becomes harder to pin down when considering changing crew members due to rotation, death, injury, illness, leave and equipment failures leading to spare planes pressed into service, errant wartime record-keeping, etc. Setting aside all the caveats for the moment, the research performed and documentation provided by Jim Lux seems to conclusively show that the 93rd Bombardment Group, 330th Bombardment Squadron’s B-24 Liberator Hot Stuff and her crew flew their 25th mission on February 7, 1943 dropping bombs on Naples, Italy, and went on to fly five additional missions thereafter, before Hot Stuff and her crew were recalled to the United States, where they were scheduled to go on a War Bonds Tour, a home front publicity junket, where combat aircraft and crews of significant accomplishment were sometimes pulled from frontline service and flown back to the United States to serve as the stirring personification of the heroism of America’s military, helping move the paper and boosting public morale.

(Image Credit: Los Angeles Daily News Archive/ UCLA)

The 303rd Bombardment Group 358th Bombardment Squadron, B-17F Flying Fortress Hell’s Angels, after which the Group later named itself, completed its 25th mission on May 13, 1943. It became the first 8th Air Force B-17 to complete 25 combat missions and at the end of their tour, the crew of Hell’s Angels signed on for a second and continued to fly, going on to fly 48 missions, without ever turning back from their assigned target no less, before the aircraft was returned to the states on January 20, 1944 for its own publicity tour.

The 91st Bombardment Group, 324th Bombardment Squadron’s B-17F Flying Fortress Memphis Belle’s crew flew their 25th combat mission on May 17, 1943, against the naval yard at Lorient, France. Interestingly, this raid was the Belle’s 24th combat mission as the original crew occasionally flew missions on other planes and other crews took the Belle on missions as well. Those uncertainties aside, on May 19, the Memphis Belle flew its 25th combat mission on a strike against Kiel, Germany, though manned by a different crew. Those who flew the Memphis Belle did seem to have particularly good luck though as none of her crew died or was significantly injured on her missions, despite being routinely riddled with bullets and damaged by flak, reportedly going through 9 engines, both wings, two tails, and both main landing gear assemblies over the course of her seven month combat career.

(Image Credit: US Army)

The story of Hot Stuff, heading home at last after at least 30 missions completed, ends in tragedy. The plane and her crew was on the return flight to the states for a War Bonds publicity and morale-boosting tour on May 3, 1943, and Lieutenant General Frank M. Andrews, Commander of the European Theater of Operations needed to get back the the states as he had been summoned to Washington DC by the General of the Army, George Marshall. Andrews and his entourage hitched a ride on Hot Stuff, and in doing so bumped five crew members from the flight. Though they were supposed to refuel at Prestwick, Scotland before heading out over the Atlantic, the crew elected to skip stopping at Prestwick and proceed to their next waypoint, Reykjavik, Iceland. They arrived to find the weather at their destination quite dicey with snow squalls, low clouds and rain. After several landing attempts, the B-24 crashed into the side of 1,600-foot-tall Mount Fagradalsfjall, near Grindavik, Iceland. Upon impact, the aircraft disintegrated except for the tail gunner’s turret which remained relatively intact and 14 of the 15 aboard died except the tail-gunner who, though injured, survived the crash.

(Image Credit: B24HotStuff)

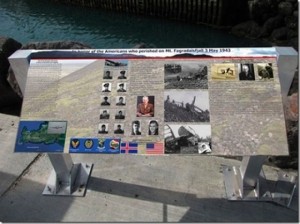

Hot Stuff and her crew were soon forgotten. Lieutenant General Andrews is remembered however, Joint Base Andrews in Maryland is named in his honor. Discovering the historical discrepancy in 1999 through a friend and fellow Commemorative Air Force member, USAF Major Robert T. “Jake” Jacobson, who was one of the bumped crew members that fateful night, Jim Lux began seeking to correct what he sees as an injustice perpetrated by history and is working on not only getting Hot Stuff and her crew their place in the history books, but is also working to have a monument erected near the site of the crash, enlisting the US Ambassador to Iceland, Luis E. Arreaga as a liaison to the Republic of Iceland and has gained the support of a growing number of other Air Force retirees who after seeing the documentation, agree that the crew of Hot Stuff is getting short shrift. Lux has also been in contact with the National Museum of the United States Air Force, turning over to them debris he recently retrieved from the site of the crash and is negotiating with the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum for a Hot Stuff display. Last month, through his fundraising efforts, Lux returned to Iceland for a 70th anniversary memorial service attended by some of the descendants of the crew of Hot Stuff and a plaque was installed telling the story of Andrews, Hot Stuff and her last, ill-fated flight with a granite monument planned to be installed at a future date.

(Image Credit: USAAF)

Doubtless, Hot Stuff and her crew deserve to be remembered for their heroic accomplishment, as does the crew of Hell’s Angels, and all the other pilots and planes who served, regardless of circumstances of their sacrifice. That the Memphis Belle and her crew had a more storybook quality to their military careers that better fit with the narrative that the government desired for home-front consumption is obvious. After all the adversity, damage and close calls, no one was ever seriously injured, and her entire crew made it home. In fact, the mythic “Memphis Belle effect” was such that there wasn’t a death among those who had served on her for nearly 40 years after her last combat flight, in defiance of actuarial norms, and Americans, for better or worse are conditioned to respond to a happy ending, especially when it goes against all probability.

The old saw goes “the first casualty of war is truth,” and it is entirely likely that there were other planes and/or crews between Hot Stuff and Memphis Belle that completed the vaunted 25 missions that constituted a “completed tour of duty,” a bar that was moved at various times to 25, 30, and 35 missions, depending on the overall loss rates, the degree of mission difficulty, as well as the conditions that they were operating in. In the end the significance of specific mission counts are completely arbitrary. That the Memphis Belle story, though abetted by a government anxious to report uplifting and inspiring stories of the war to its people at home, captured the public’s imagination, doesn’t make the story any less inspiring and does not and should not be perceived as taking something away from the countless others who made sacrifices for their country, just as the recognizing the achievements of the crews of Hot Stuff and Hell’s Angels don’t diminish the sacrifices made by those unfortunate souls who went down in flames whether on their first, fourth or 24th mission in service to their country.

There will always be those who subscribe to particular yardsticks though, so to summarize:

Hot Stuff was the first B-24/crew and the first “heavy bomber” to complete 25 missions on February 7, 1943.

Hell’s Angels was the first B-17/crew to complete 25 missions on May 13, 1943.

Memphis Belle’s crew completed 25 missions May 17, 1943 (without any loss of life).

Memphis Belle, the plane completed her 25th mission on May 19, 1943 (without any loss of life).

Those interested in Hot Stuff and/or are looking to support the erection of the Icelandic monument to the brave men who served on her can connect with the organization HERE or the group’s Facebook page.

More information on Hells’s Angels is available HERE.

WAS TOO YOUNG FOR THE BIG ONE, HOWEVER I MADE IT TO KOREA AND VIET NAM BEFORE RETIRING IN 1969. WAS ALWAYS INTERESTED IN FLYING AND THE GREAT MACHINES.SO MUCH SO THAT I ENLISTED IN AIRFORCE AT 18 AND 1/2 YEARS OF AGE….FORTUNATELY WAS ABLE TO GO TO 3 TECH SCHOOLS PLUS FLIGHT ENGINEERING SCHOOL….JUST MISSED FLYING STATUS IN KOREA AS I WAS CLEARED FOR FLIGHT IN KOREA JUST AFTER I MADE THE LIST FOR ROTATION BACK TO US IN 3 MONTHS…I BELEIVED IN LONGEVITY SO DEEPLY THAT I QUICKLY CHANGED OUR MINDS ABOUT FLYING STATUS IN THE WAR ZONE. ANY WAY I HAD FLIGHT EXPERIENCE ON THE B 26 TOWING TARGETS HERE IN THE GOOD OLD USA. AFTER THAT I WAS SENT TO KB-29 AIR REFUELING SQ IN LOUISIANA. (MAINTENANCE ON KB-29) THIS PROVED TO BE A WORKING NIGHTMARE, SO I MADE TO FLIGHT ENGINEERS SCHOOL AT CHANUTE AFB, IL. IN 1959..FROM THERE BACK TO LOUISIANA WHERE I CHECKED OUT AS ENGINEER IN THE KB-50 AIRCRAFT…ABOUT 2000 HOURS THERE, THEN TO HUNTER AFB GEORGIA TO FLY THE GREAT C-124. WHAT A GOOD FLYING, FORGIVING AIRCRAFT WITH PLENTY OF POWER WITH 4 R-4360 PRATT WHITNEY ENGINES….PLENTY OF FLYING EUROPE FROM HOT WEATHER IN SOUTHERN ITALY TO THE COLD OF ABOVE THE ARCTIC CIRCLE. THEN TO JAPAN WHERE WE SUPPLIED ALL THE FAR EAST WITH CARGO GOING AS FAR EAST AS BANGKOK THAILAND, IN COUNTRY NAM, PHILLLIPINES, KOREA AND OTHER POINTS THERE IN. GOOD PART OF THIS IS THAT THE WING H Q WAS AT HICKAM FIELD HAWAII…ALWAYS A PLEASURE THERE FOR THE ANNUAL FLIGHT SIMULATOR AND CURRENT GROUND TRAINING EDUCATION.

FROM TACHIKAWA TO ROBBINS GA. FOR FINAL PROCESSING OUT TO A GREAT RETIREMENT……….

I, too flew the C-124, first from Travis, 1956-58, then Hickam 1958-9; and later (college break) Dover, 1963-5, and McChord, 1965-7. Perhaps our paths crossed, as I was in the front seats of that magnificent noise-maker. I have some 7500 hours at the controls, never for an instant not valuing the knowledge and expertise in that sideways sitting position, behind me. Before anything, consult the FEO! Written in pencil on the pouter skin behind the scanner’s hatch: “Pilots are a funny bunch – what we call pussy, we call lunch.” That wasn’t you, was it? (LOL). I miss old shakey, but I enjoyed flying Pan Am’s B-727 even more (a career with PAA followed, 1967-91).

sorry – “what we call pussy, they call lunch.”

Very cool story. But ‘Mighty Eighth War Diary’ shows no raid on 2/7/43. A raid on 14 February is listed as the 34th 8th Bomber Command mission. The 93rd BG dispatched aircraft on 9 of the first 34 raids by 8th BC. So whatever “Hot Stuff” was doing it wasn’t going on raids conducted by 8th BC.

Hot Stuff was in the 8th Air Force 2nd Air Division, 93rd Bombardment Group, 330th Bomb Squadron. It flew in both the ETO and North Africa. It made its first mission on Oct. 21, 1942 over Lorient, France. It was sent to North Africa to support the 12th Air Force after its 10th mission in the ETO and returned to Hardwick, England in February 1943 after completing its 27th mission. It completed four more missions to Vegesack, Wilhelmshaven (2) and Rotterdam before being retired from combat on March 31, 1943. It flew most missions unescorted and saw plenty of flack and enemy aircraft.

One reason it survived was the tail gunner had six confirmed kills and several more unconfirmed.

I’m have no dog in this hunt. The B-17 and B-24 were both great airplanes. I’m just conveying the facts I uncovered while researching information for a friend who was the bombardier on Hot Stuff. He, the copilot and two other crewmembers were bumped from the flight back to the U.S. by Lt. Gen. Andrews, his staff and three chaplains. All onboard were killed except the tail gunner when Hot Stuff crashed into mountain in Iceland on May 3, 1943.

There were many B-24s in the 8th Air Force that completed 25 to 30 missions long before the first B-17 Hell’s Angels or Memphis Belle completed their 25th.

Hot Stuff completed its 31st mission on March 31, 1943. Hell’s Angels completed its 25th mission on May 13, 1943 and the Memphis Belle on May 19, 1943.

Irving Ostuw died this 11/29/14. His ob states he flew 125 combat mission over Europe in his P-47 bomber and received 3 Distinguished Flying Crosses and 24 Silver Stars. I guess flying a P-47 doesn’t count, only B-17 & B-24 when it comes when it comes to keeping records. Why?

Probably because the P47 was a fighter, not a bomber.

Yes, they did use the JUG in ground attack, but that does not make it a bomberby any stretch of the imagination.

Further, this isn’t really obvious if you take a cursory look at 8th AF operations, but the B-24 groups didn’t start large scale operations until after the P-51B was available. It was the B-17 going toe to toe without fighter escort with the GAF that is at the heart of the story of the 8th AF. This in no way denigrates the contribution of the B-24 crews.

Good day! I simply wish to offer you a huge thumbs up for your

great information you have got right here on this

post. I am returning to your web site for more soon.

backflip

Helpful info. Fortunate me I discovered your site by chance, and I’m stunned why this twist of fate

did not took place in advance! I bookmarked it.

As the son of one of the “Hot Stuff” crewmen bumped from the ill fated final flight, I was unaware of the fate of Gen Andrews, his entourage, and remaining crew. Grant Rondeau only told us that he wasn’t aboard the final flight. The bumped crewmembers were told that they were to remain in England to train new crews. The reason for this misinformation seems to have been to obscure the fact that the Supreme Commander was absent the theater. Following the loss of “Hot Stuff” it wasn’t a good idea for the Axis to be aware of the demise of the Supreme Commander. General Andrews, considered to be the father of the modern USAF, was replaced by Gen. Dwight Eisenhower

Hot Stuff and crew were in the 9th from the begining of Dec 1942 on, flying missions from bases in Africa. Unlike the 8th, the 9th didn’t had a set limit of 25 missions. The limit was based on other factors, like degree of difficulty and the places they were operating from.

It’s a great thing for any crew/plane to have completed 25 missions, but I think the 8th flying to the heart of Germany had a tougher nut to crack than the 9th flying against targets mostly in Africa and Italy (although nobody had a tougher target then Ploesti).

The Belle is also known as the first (and one of only three) a/c that completed its tour without losing a single crewman.

Belle crew was not intact through out the 25 missions. BTW, 9th AF mission credit was 300 combat hours meaning you had to complete the raid. Double credit missions were more about long/latitude vs how hazardous the target was. Example: Ploest was single credit.

I was completely unaware that “Hot Stuff” had beaten “Hell’s Angels” and “Memphis Belle” to the 25 mission mark. I have amended the B-24’s loss on the Wikipedia article List of accidents and incidents involving military aircraft (1940–44) to reflect this.

The B-17 Delta Rebel II of the 91st BG, piloted by Capt.George Birdsong,Jr…. completed her 25th mission on May 1,1943. How do I know this for sure? I have the Bombardier Bob Abb’s flight log book….straight from his widow’s hand to mine twenty years ago…untouched…unmolested…and he recorded it in ink in his own hand. Just sayin…….

Many thanks for the message Monty… That sounds like a fascinating artifact. We would love to see some images from that log book if you feel comfortable scanning and sending them along! Perhaps you would be interested in submitting an article yourself? Please let us know…

I read several years ago somewhere on the net that the Delta Rebel II didn’t get recognized because of it’s name and Confederate soldier painted on the nose. PC even then.

Yep, my pawpaw flew on that bird. His name was B.Z. Byrd. He said it was all politics.

I guess the RAF must have had it much easier than the 8th Airforce. http://www.yorkshireairmuseum.org/air-museum-news/recalling-how-halifax-friday-the-13th-got-its-name

Dad flew 37 missions for RAF. My hero. P. S. He’s here to tell the stories.

Hi,

I’m hoping you can help. I’m trying to find out how many B17’s were operational in the European Theatre of Operations. As far as I can work out, 3086 were lost but have no figure to work with to find a percentage. I’m trying to work out the losses to compare it with the losses of the Avro Lancaster which peaked around 44% of total. More B17’s were built than the Lancaster, but some, many, were used in the Pacific Theatre as well.

Many Thanks

I have heard some units had diaries. Does anyone know if the 330th Squadron of the 93rd Bomb Group has such a diary? Special interest is the year of 1943. Thank you.

A great resource for some of the 8th AF B-24 groups is “TED’S TRAVELLING CIRCUS” available at Amazon and elsewhere. The 328th. 329th and 330th squadrons were under Ted Timberlake.

One of my relatives was in the 330th, Captain Hugh R. Roper, He piloted B-24D “Exterminator”, 41-23717. He was lost on his 25th mission, the low-level raid on Ploesti, August 1, 1943. I have his diary which chronicles some of the activities of the 330th in 1943.

My dad, Charles R. Toner, was a B-17 pilot who completed his 35 missions in 1944. He joked that after WWII, raising six kids was a piece of cake.

My uncle, by marriage, was a waist gunner with the 8th, I believe. We were having some drinks and I was listening to some of his “war stories” when he told me he had flown 137 missions. I told him he was telling lies. So he promptly retrieved his discharge and it stated he had really flown 137 missions. Dick is a long time dead now, but I would like other confirmation. I only know he was somewhat of a wild man with numerous shrapnel scars. His discharge also stated he was to pay child support to one woman in England and one in France. Told you he was a wild man.

My Dad flew 25 missions in a B-24 and B-29 with the 8th AF /466th bomb group. I was told that 25 missions was the max and they never told you when your next mission was for worry that word would leak out. As a 24 yr old Capt and pilot,he said when you dropped all your bombs,you headed back or did “splash missions with the P-51’s. You didn’t know if you would be headed back out on another mission in 24 hours or 5 days. I’ve always heard that anyone saying they flew more than 25 missions was a liar. Now I don’t know what to believe! God bless all of our heroes in WW2.

Ron,

My father’s Bomb Group on Guam, hosted three crews from the 8th Air Force, 346th Bomb Group.

The 314th BW needed replacement crews and the 8th AF crews were to absorb experience, which they could later pass on to their fellow crews. So on July 5, 1945 the 8th AF landed on Guam . They were the only crews in their squadron to see combat with the 20th AF. So, the answer is YES, if anyone ever asks you if the might 8th AF ever bombed Japan.

my friend Russell Erickson piloted 33 mission in the b24 L

ouisana belle from England.

I am trying to find information on my uncle, Joseph Farese, who was a bombardier/navigator and flight officer in the 5th BG, 72nd BS, 13th AF and was in the Pacific Theater, Philippines, etc. I am trying to find information on which B-24 crew he was a member of but I am not having much luck. I was able to find a B-24 named “Red Headed Woman” Liberator #645 (44-41645) that was part of that exact group and the time frame is correct, but I cannot find anything definitive. Any help or direction would be greatly appreciated.

My brother and I were having a disagreement over how many missions bomber crews had to fly (was this figured by individual? I have no idea). My father was in a B-24 stationed in Italy and flying up over the Balkans and Germany. According to my brother, it was in the Ploesti raid that their lost all their fuel when anti-aircraft shells went through their wings without exploding. So they parachuted out and spent three days walking back from behind enemy lines in Yugoslavia.

My brother said it was their 49th mission. I say it was their 24th. IT was their 24th, right?

I also have an anecdote, but I’m not sure which bomber group he was in. A radio operator, he was in the crew of one of two bombers that in which the group leader flew, with radar where the belly gunner would normally be. The group leader sometimes flew in one, sometimes the other. According to my dad (deceased January 1, 1991 in an automobile accident), they would occasionally fly to Cuba, sell or trade whatever equipment they could, buy as much alcohol as they could and fly that back to Italy. He said they would literally strip the plane, but I don’t remember if that was before they left Italy or in Cuba. Does that sound like a truthful story?

A claim is made that Gene Roddenberry, screen writer for Star Trek, completed 89 missions in the 324th bomb squadron. The unit used B-17s, according to what I read. That seems awfully high for a pilot, which is what they say he was. There is some report that 25 missions was a full tour with that group, which would indicate more than three tours.

It is mentioned that the units flying out of Africa and Italy had no such standard mission tour cap . My cousin, a radioman and gunner, had 50 missions, flying the last day of the war, in a B-25. He told me (and has since passed away, so I can’t verify it, that 37 missions was the cap and he was on his second round. An amusing sidelight was that he was highly indignant that every third mission they got liberty and that at 50 missions , they were one short and did NOT get liberty, even though the war in Europe was over. And yes, I have some “unofficial” photos of the B-25 aircraft and activities in Italy.

Ellen:

A dear friend of mine was the navigator/turret gunner of the lead plane on the 2nd “successful” Pelosti mission and I saw the commendation for that and for the 50 missions that B24 crew made.. He has shared a diary of the 50 missions that will be made public upon his passing.. THE GREATEST GENERATION OF AMERICANS!!!

My dad was a waste gunner on a B 24 in ww2. He was in the 389th bomb group, 567th squadron. I know he flew at least 32 missions because I have his hand written log where he documented each mission and what he did. He was also involved in one of the Ploesti fields mission. He got a certificate for “The Lucky Bastards Club” for flying at least 30 missions and includes a list of all his missions. I’m just now gathering all these materials from a box of memorabilia We have.

Doesn’t matter who was first. Both crews are GODS! I live by HAFB museum and visit every Memorial Day. Short Bier is housed here.

My father Thomas “Jack” Showers served in the 330th of the 93rd from December 1943 to some time after July 25, 1944, when he completed his last combat mission. I recently found his combat flight records and most interestingly a certificate stipulating the 33 completed combat missions he flew. If I recall correctly (at least in the 330th) the 25 mission count only included completed primary target missions. Turn-arounds, aborts and alternate target missions did not count, even though those flights may have encountered enemy defenses before terminating the mission. This may may account for individuals citing very high mission counts as they may have counted flights that did not include successful strikes on primaries. Just to add some fog to the issue, the my father’s certificate of mission completions had only 30 places to list missions. My father’s had an additional 3 missions typed into the margin. I hope my information is correct. My father like most of the true heroes of that war rarely spoke of the action he saw in the war except to say that few of his friends came home with him.

What about 50 mission B24 pilots???