by Richard Mallory Allnutt

As readers are probably well aware, the Military Aviation Museum (MAM) expects to add a Mitsubishi A6M ‘Zero’ to its flying collection in the near future. This former Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) fighter is approaching the end of a decades-long restoration effort, culminating with Legend Flyers at Paine Field in Everett, Washington. While a handful of hurdles remain before our Zero can make its first flight, and eventual trip to her new home in Virginia Beach, that time is fast approaching. As the museum’s Curator of Digital Media, I thought readers may be interested in learning more about the aircraft’s history…

During the years since its recovery from a Pacific island in 1991, a lot of information about the aircraft has filtered out; some of it well-sourced and some of it not. About a year ago, we at the Museum began wading through this mountain of data with the intent of providing greater clarity regarding the airframe’s history. What we know so far has been generated through countless hours of research, consultation with experts in the field, access to US, Australian and Japanese archives, along with primary source material from the war years. Our goal here is to present as accurate a picture of our Zero and the human story surrounding it as presently possible. With research still ongoing, subsequent articles will no doubt expand on key areas of the story, (please let us know if you want to help!), but here is what we know so far.

The Zero:

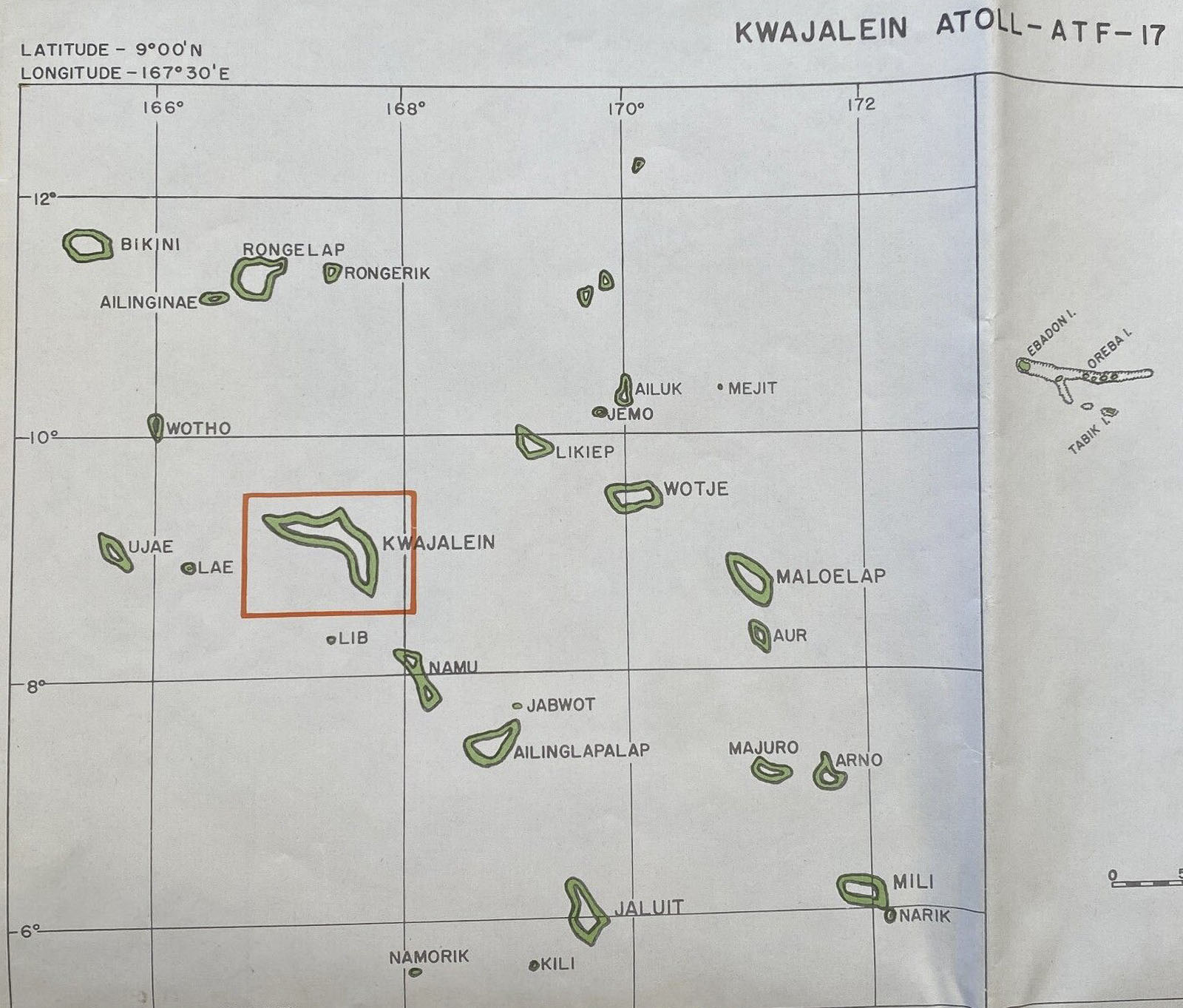

MAM’s Zero is based around the substantial remains of two different A6M3 Model 32s which served in the Marshall Islands with the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) as serial numbers 3148 (forward fuselage & wings) and 3145 (rear fuselage & tail). While we do not know for sure, it is possible that these two Zeros were combined during the war to produce one airworthy airframe from two damaged examples. According to Volume 16 (Mitsubishi Heavy Industries) of the exhaustive U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey completed just after WWII, both of these aircraft went through final assembly at Mitsubishi’s No.3 Airframe Works facility in Nagoya during September, 1942. Soon after their manufacture and flight testing, the two fighters – and more than a dozen others – made the long journey by sea from Nagoya to the Marshall Islands, almost certainly via the major Japanese naval port within Truk Atoll. The ultimate destination was likely Roi-Namur, a twin-island base at the northern tip of Kwajalein Atoll, and home to the headquarters garrison for Japanese naval aviation in the Marshalls at that time.

The Marshall Islands

Just north of the equator in the Western Pacific, the Marshall Islands archipelago, and numerous other island groups in the Western Pacific, had been under de facto control of the Japanese Empire since late 1914. Japan had annexed all of Germany’s possessions in the region at the onset of WWI, a time when the nation was allied with the Western powers. The changing geo-political climate of the post-WWI world however, eventually lead Japan to militarize the islands, despite previous agreements forbidding this outcome. A massive construction program began in earnest during 1939 and, as soon as suitable facilities became available, land-based units from the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service took up residence in these far-flung colonial outposts. Several atolls in the Marshall Islands Archipelago received new air bases during this process, with aircraft from the Chitose Kōkūtai (Chitose Air Group) comprising the vanguard.

The Chitose Kōkūtai

Many IJN air groups gained their names from the locations where they first established or for the aircraft carriers with which they sailed. Named for a region of Hokkaidō, the Japanese home island where the air group formed during October 1939, the Chitose Kōkūtai initially served as a training unit. But as the IJN expanded its island outposts, the Chitose took on a frontline role, deploying to the Marshall Islands during 1941 as part of the 24th Kōkū–Sentai (Air Flotilla).

With a primary base on Kwajalein Atoll, the unit also maintained satellite stations on several other Marshallese atolls. Here the aircrews worked up their readiness for a war which many of them, even then, did not believe would actually arrive. Indeed, in late December 1941, members of the squadron were surprised to find themselves participating in the attack on (and eventual capture) of the U.S. base on Wake Island, just north of the Marshalls.

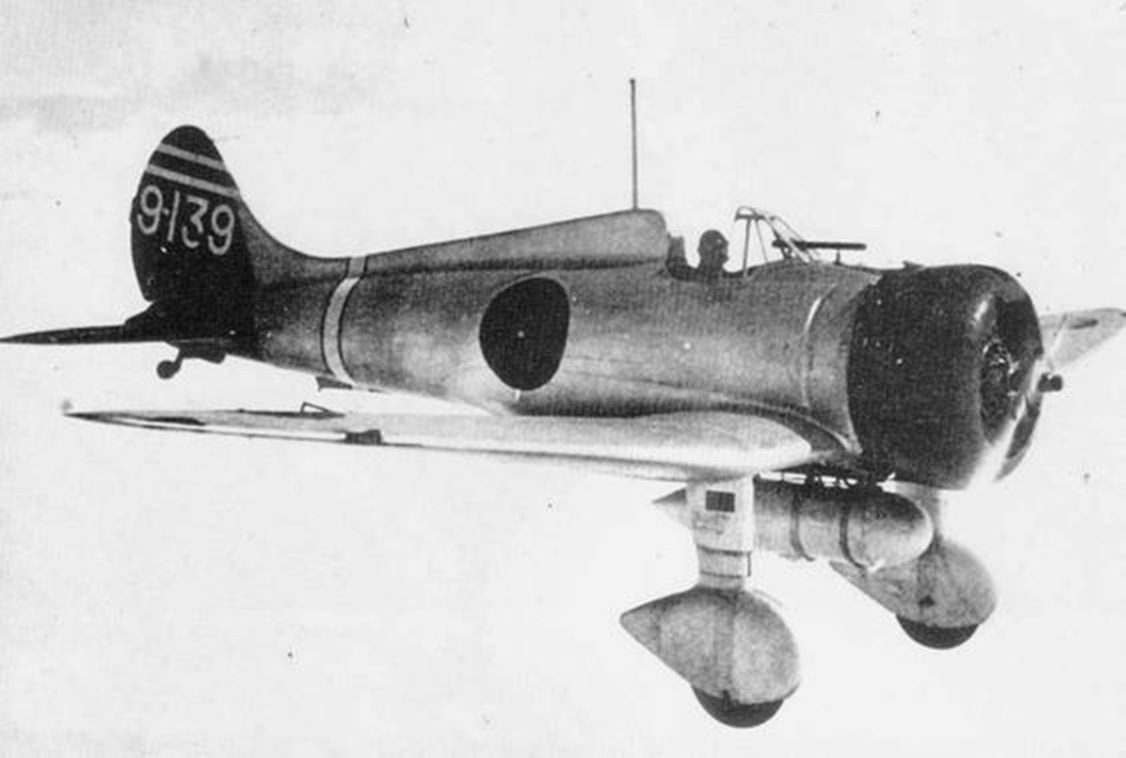

When the Chitose first arrived in the Marshalls, the Mitsubishi A5M Type 96 served as its primary fighter aircraft. The A5M became the world’s first low-wing monoplane shipboard fighter following its introduction in 1936. Designed by the legendary Jiro Horikoshi, aged just 31 when the A5M first flew in February 1935, the fighter proved highly effective in combat over China, despite lacking the range to escort long-range bombing missions. Horikoshi began working on the revolutionary A6M Zero just two years later. At the time of its introduction over China during mid-1940, the Zero utterly dominated. It was easily the finest fighter aircraft in the world at that time. Agile, fast and with incredible range, the aircraft also packed a serious punch with a brace of wing-mounted 20mm cannon and two 7.7mm machine guns in the fuselage. Production rates were relatively slow, however. Indeed, when Japan declared war on the United States in December 1941, the IJN still only had a few hundred Zeros in its fleet, reserved primarily for frontline carrier units. As a result, the Chitose Kōkūtai did not receive its first A6Ms until February 1942, but even then it was just a handful at first – and only for those elements seconded to frontline positions in the Southwest Pacific. Many more Zeros would arrive in the Marshall Islands before too much longer, however.

Based upon vestigial markings on Zero s/n 3145’s tail fin, we know this aircraft first served in the Chitose Kōkūtai; likely beginning in late October or early November 1942. While the tail fin from 3148 is not known to have survived intact, it seems likely that the airframe belonged initially to the Chitose as well, although the association of both airframes with this unit did not last long. In accordance with an IJN directive dated November 1st, 1942, the Chitose Kōkūtai disbanded; its fighter element reforming as the 201st Kōkūtai (201 Ku), while the bombers were split between the newly-formed 701st and 702nd Kōkūtai. Each of the other ‘named’ air groups within the IJN went through a similar process at around the same time, the resulting units each receiving numerically-based identifiers as well.

Other than a frenetic period during early February 1942, when the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 8 (under Admiral William Halsey) unleashed a series of ‘smash-and-run’ air strikes and naval bombardments in the Marshalls, the archipelago remained relatively untroubled by war until deep into 1943. It is perhaps for this reason that the IJN transferred the 252nd Kōkūtai to the Marshall Islands in February 1943. The unit replaced the 201st Ku, but retained its aircraft (including our Zeros). Pilots from the 252nd Ku badly needed to regroup in more peaceful climes at this point. Formerly comprising the fighter contingent of the Genzan Kōkūtai, 252 Ku’s pilots had endured a thorough mauling from Allied forces in the Solomon Islands region. With a brief stint in Misawa after withdrawing from Rabaul, the Marshall Islands must have felt like the perfect backwater for 252 Ku to season its new aircrew.

War Reaches the Marshalls:

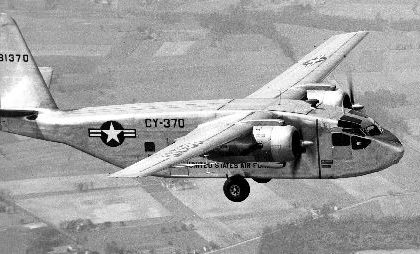

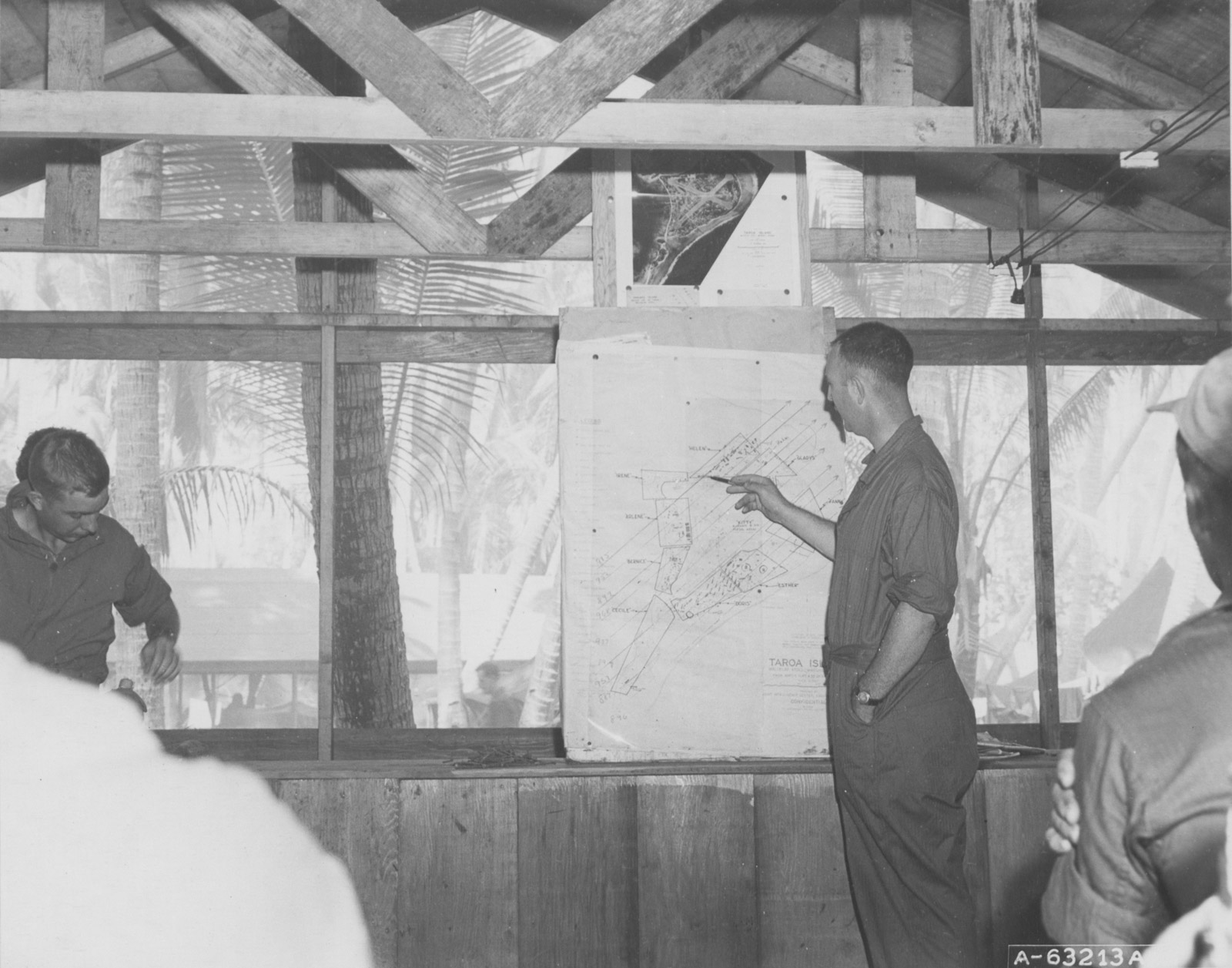

As the Allied cause rallied, then steamrolled its way inexorably through Japanese positions in the Southwest Pacific, the Marshalls soon came within range of heavy bombers from the U.S. Army Air Forces; primarily B-24 Liberators belonging to the 7th Air Force. The 7th AF began a ferocious campaign against IJN bases in the region during the fall of 1943. U.S. Navy and Marine Corps aerial units entered the fray at around this time too. Expecting invasions along the outer edges of the Marshall Islands first, the Japanese stationed their aerial forces accordingly. As a result, most of 252 Ku’s remaining fighter strength positioned itself on Taroa Island towards the end of 1943. This is where most of them met their fate, bombed out, strafed or shot down during an all-out aerial blitz on the island and neighboring atolls during late January 1944.

Taroa Island:

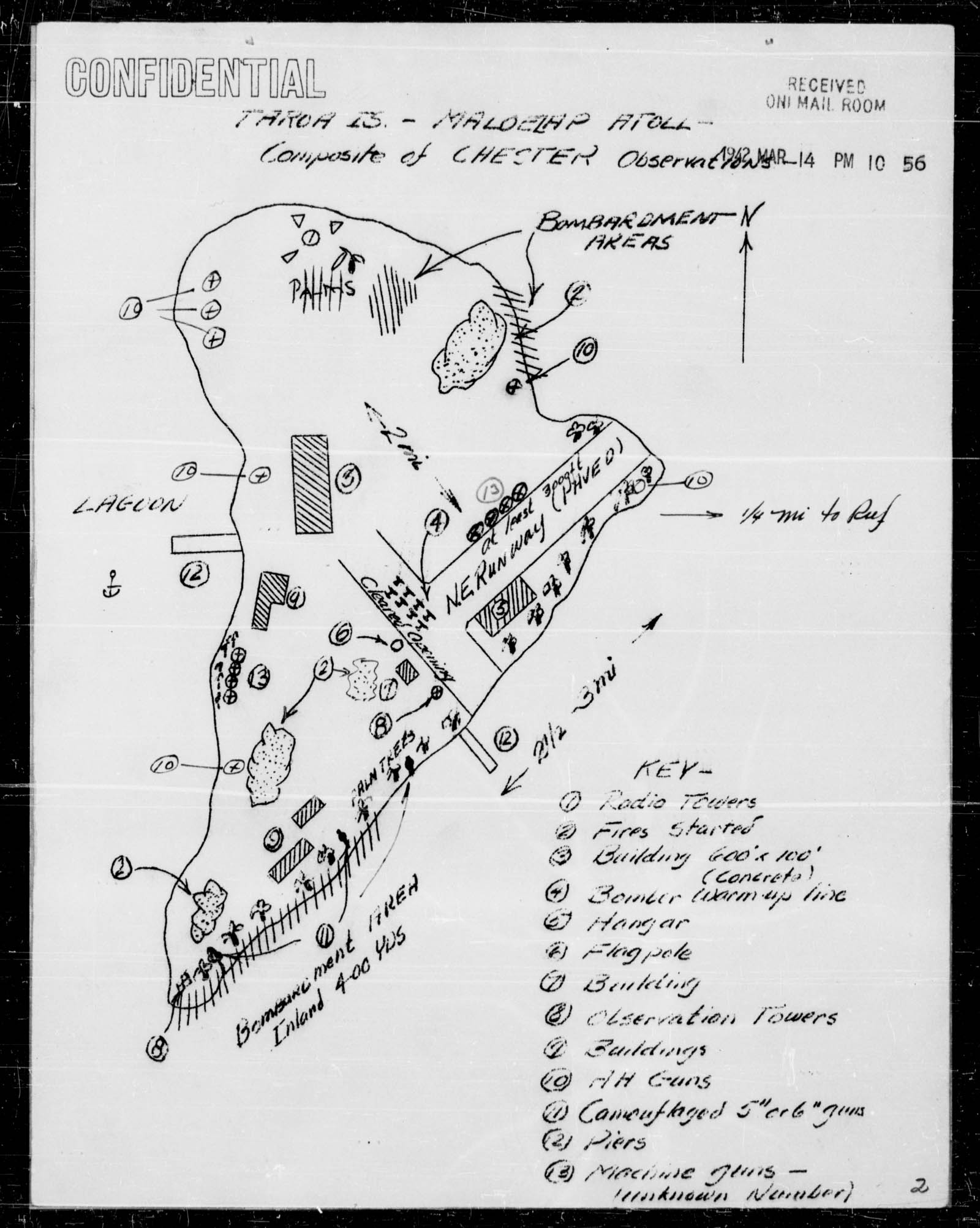

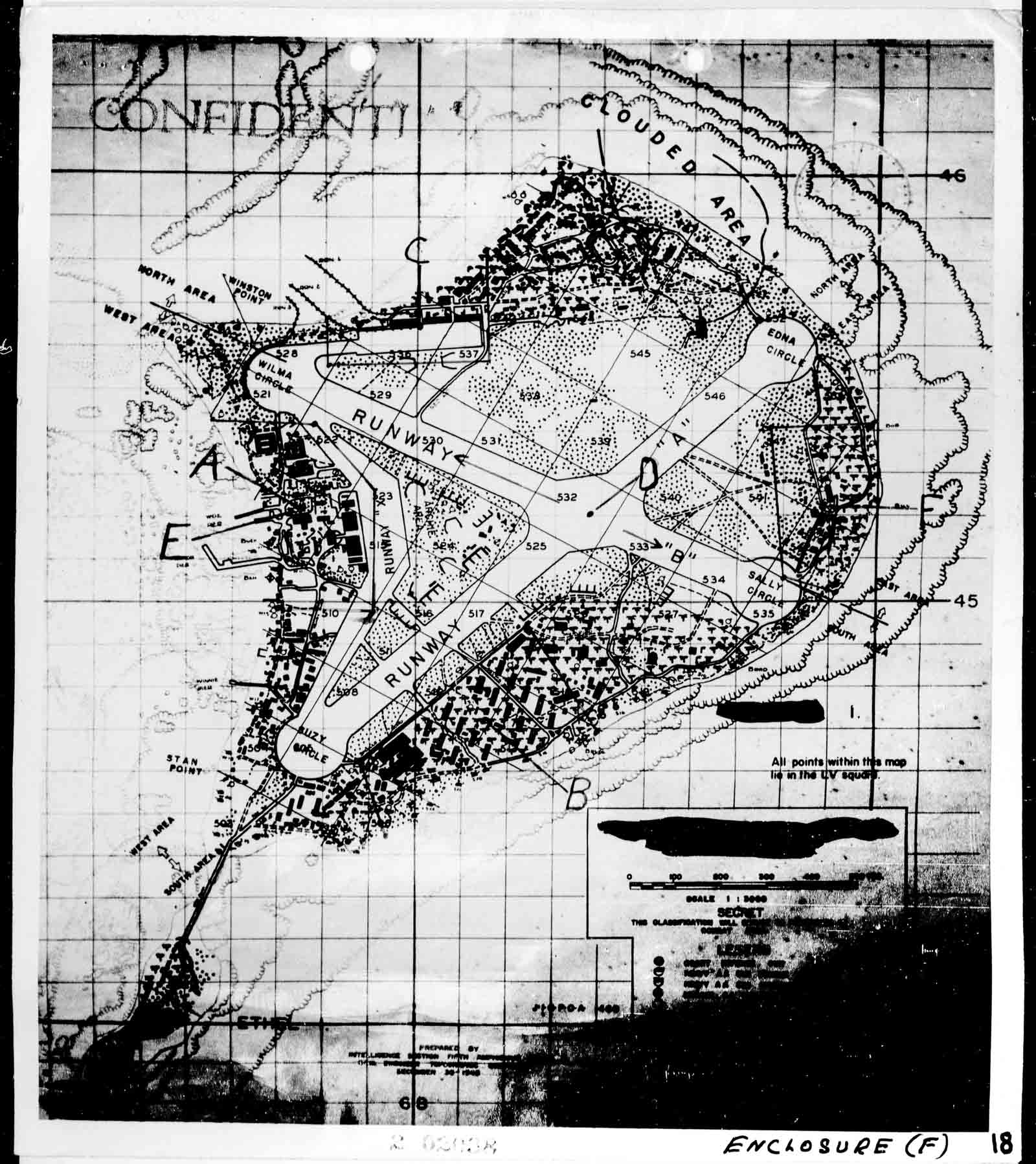

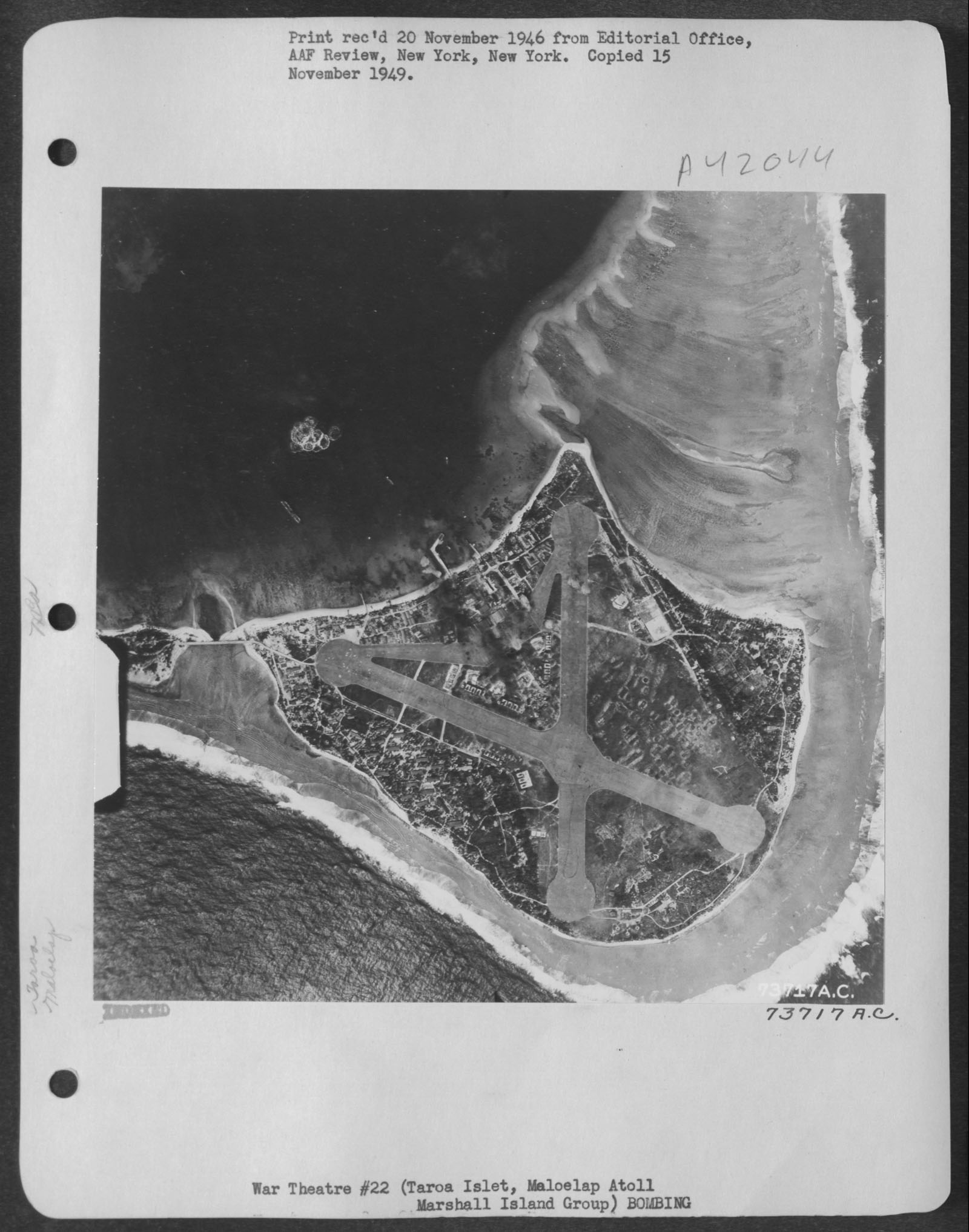

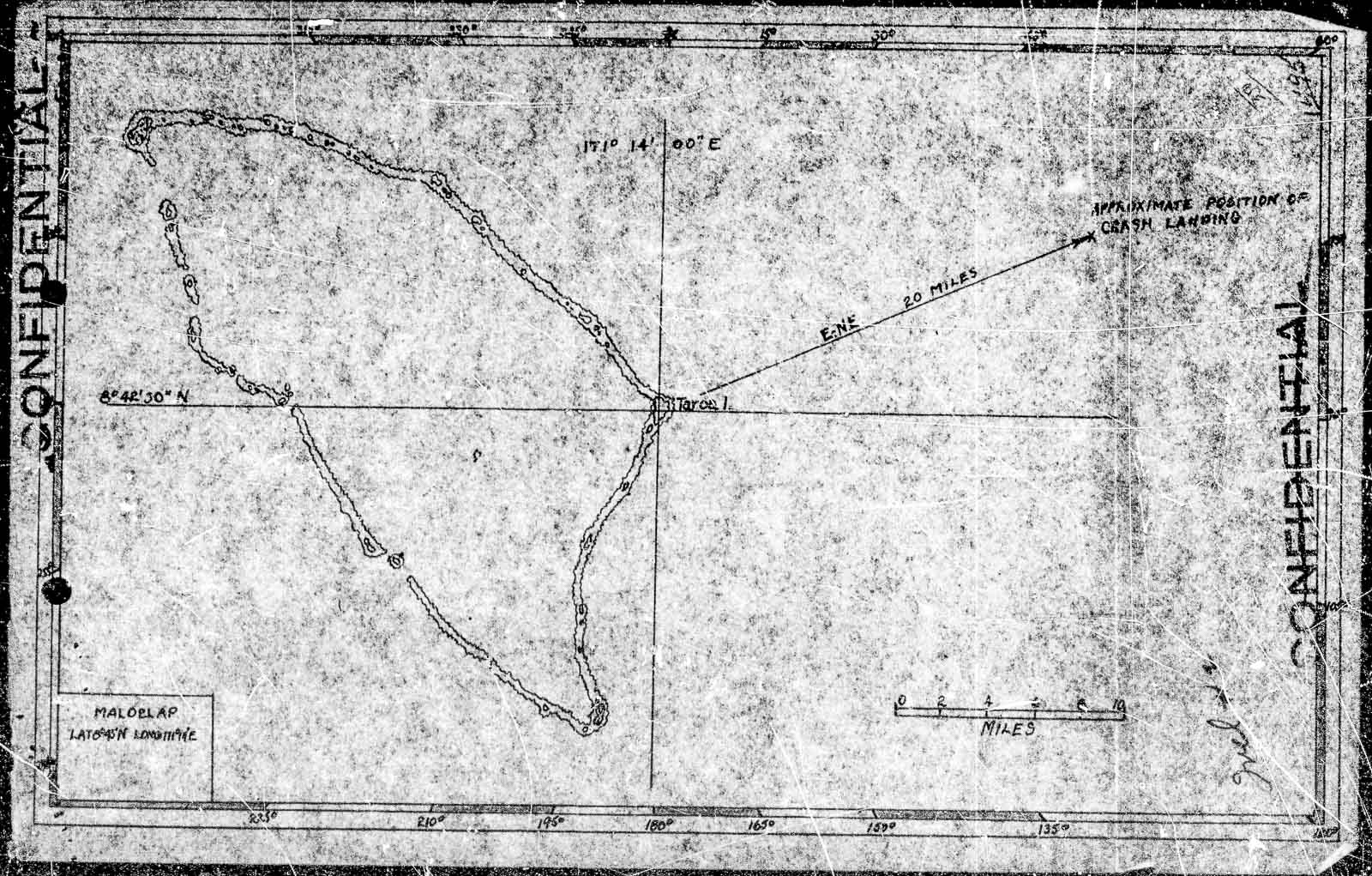

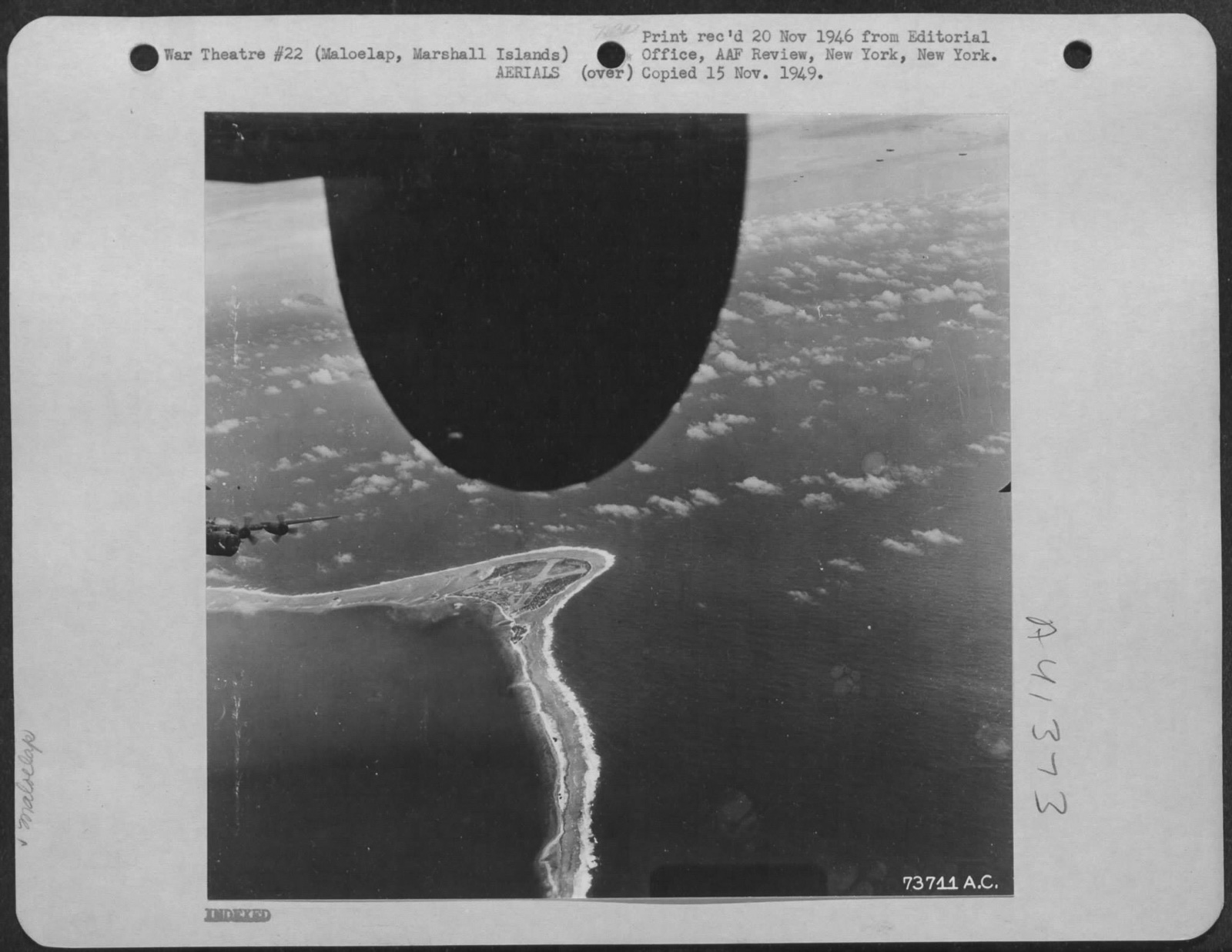

Despite a surface area of well under a square mile, Taroa Island is the second largest of seventy one specks of land rising (barely) above sea level in the Maloelap Atoll, which lies roughly 8° north of the equator. The island’s small size belies its importance during WWII. Situated along the easternmost edge of the Japanese Empire, it served as an important observation and defensive outpost. By February 1942, Taroa possessed a freshly-completed pair of runways (one 4,800’ and the other 4,100’), a seaplane base, a radar station, a naval pier and nearly 400 military buildings and bunkers along with a garrison of some 3,100 military personnel, Korean ‘laborers’ and Marshallese. A dozen or so medium artillery pieces (a mixture of Japanese and British designs) formed the primary coastal defenses, supplemented by numerous anti-aircraft guns scattered across the island – an arsenal which proved relatively potent when called to action.

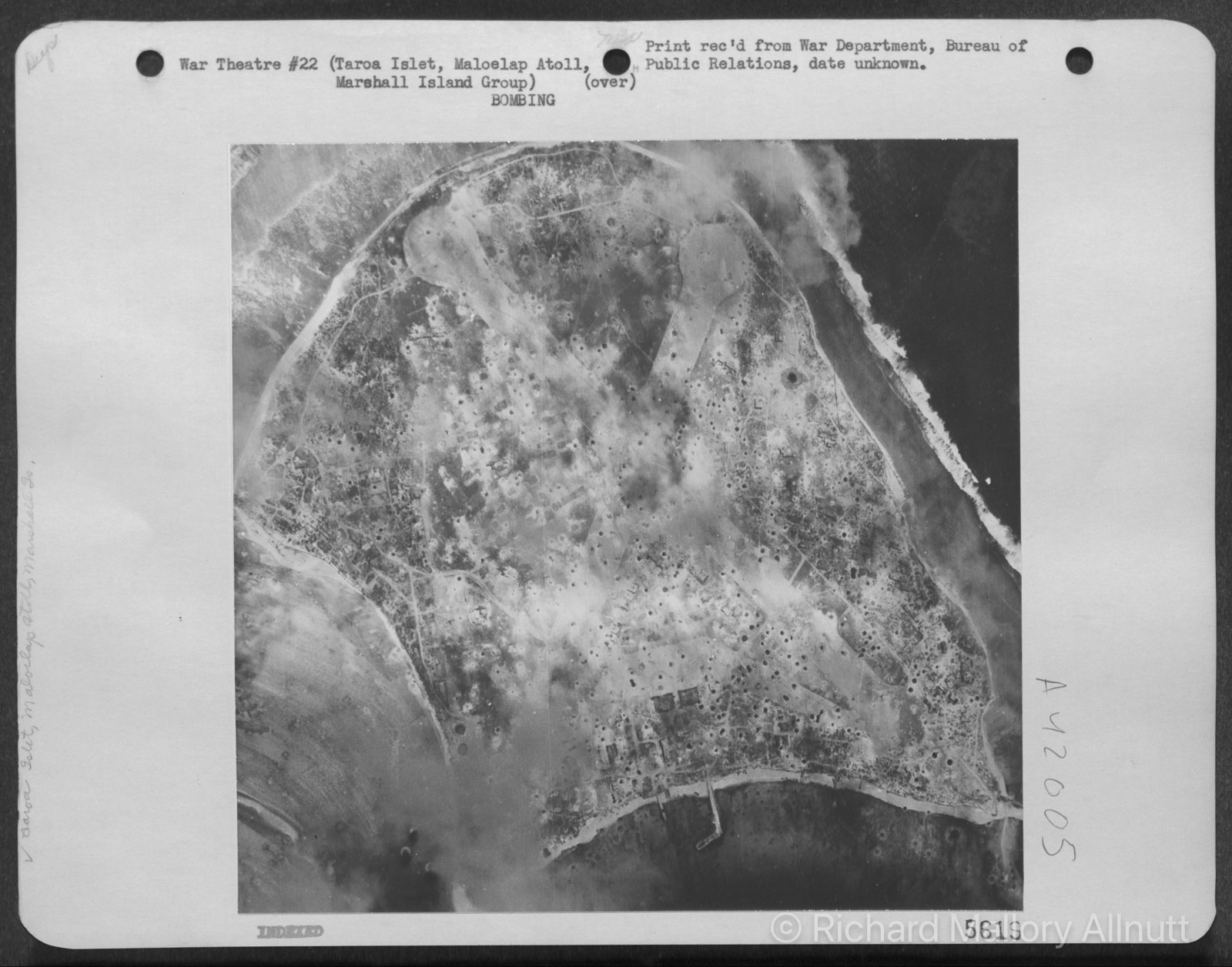

The relative peace of island life began slipping into calamity during the summer and fall of 1943. By November, the IJN base, and others in the Marshalls, received regular visits from B-24 Liberators belonging to the 30th Bombardment Group based in the Ellice Islands, some thirteen hundred miles to Taroa’s south east. While Taroa’s Zeros tangled with these B-24s, and it is likely that the two A6M3s which make up the Museum’s example were amongst them, they do not appear to have been particularly effective in that task. In reading through Missing Aircrew Reports at the U.S. National Archives which cover the handful of B-24s (and their crews) shot down on those raids, eye witness statements from personnel aboard adjacent bombers all state that accurate anti-aircraft fire was the primary culprit behind Liberator losses.

These bombing raids served as a prelude to Operation Flintlock, the U.S. invasion of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands between late January and early March 1944. Rear Admiral Charles Pownall, leading the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 50 with its four fleet carriers (USS Lexington, Essex, Yorktown and Intrepid) steamed through the Marshalls, giving Maloelap Atoll (and Taroa Island in particular) a thorough pounding on January 29th/30th, 1944. Rather than invading Maloelap, however, Flintlock bypassed the atoll and several others to strike at the heart of Japan’s Marshallese positions at Kwajalein Atoll, which the 4th Marine Division and 7th Infantry Division successfully invaded during the first week of February, 1944. Most other Japanese bases in the Marshalls were then left to ‘wither on the vine,’ as it were. Those marooned on these now-isolated atolls, unable to leave and bereft of supplies, still received a near-daily pummeling from U.S. naval and Army Air Forces units until near the very end of WWII. No longer of strategic value, they essentially became benign, though realistic combat training grounds for green Allied pilots.

Despite regular bombings, disease and starvation became the leading causes behind most casualties experienced on these islands. Just over a thousand people of the initial 3,100 survived on Taroa when the war came to a close; U.S. forces evacuated everyone soon after. It wasn’t until the early 1970s when Marshallese civilians returned to live on Taroa Island permanently, with a hundred or so residing there presently. Remnants of the Japanese occupation, including numerous aircraft hulks, remain littered over the island, albeit mostly overgrown by vegetation today. It is still hazardous to dig anywhere, of course, due to the profusion of unexploded ordnance – even now. Reportedly, U.S. Forces dropped some 3,500 tons of bombs and 450 tons of naval artillery shells on the island in WWII!

The Recovery:

It was under such conditions that brothers John and Tom Sterling (along with Lavon Webb) camped out on Taroa for three months in 1990 as they searched for suitable IJN aircraft hulks to salvage. They ended up recovering enough airframe components for roughly two complete Zeros, hauling them back to John Sterling’s base in Boise, Idaho by May 1991. One of these airframes, an A6M3 Model 22 with serial number 3489, was largely complete, albeit very battered. Sterling eventually sold that airframe to the Imperial War Museum in the UK which now displays it in ‘as-found’ condition. The other Zero, basically a forward fuselage with wings (separated at the root) and a sawn-off rear fuselage, was initially unidentifiable. While subsequent articles will delve deeply into the story behind its eventual identity, we are confident beyond any doubt in stating that the forward fuselage and wings belonged to A6M3 Model 32 serial number 3148, while the rear fuselage once belonged to A6M3 Model 32 serial number 3145.

On closer inspection, 3145’s rear fuselage bore some unusual markings identifying it as a Patriotic Presentation Aircraft. Future articles will delve into this fascinating arena as well but, suffice to say, the manufacturing costs of such aircraft were formally subsidized by private sponsorship from Japanese civilians, corporations and other organized domestic entities. The names of those sponsoring the aircraft were emblazoned upon the fuselage, along with a unique, identifying number referred to as a Hōkoku-Go (HKK for short). While the actual HKK number had been cut from the airframe (likely souvenired by a U.S. serviceman circa 1946) the sponsorship name remained identifiable in the heavily weathered skin. After carefully tracing out the markings on the fuselage skin, the following seven kanji characters were revealed (with a less distinct eighth, TBD).

满洲國中等學校?

While we will describe this process in greater detail in a subsequent article, translating these characters revealed that the manufacture of A6M3 32 s/n 3145 was sponsored by the students and personnel within the Manchukuo Secondary School system (Manchukuo being the Japanese puppet state established in occupied Manchuria during 1932). This discovery proved fascinating, and adds extra depth to the history of the aircraft.

The quest was then on to determine what 3145’s missing HKK number could have been. Sadly no definitive list of HKK numbers is known to survive, although there is a fair amount of photographic evidence tying specific airframes to specific HKK numbers. Wartime documents also survive which link specific HKK numbers to their sponsors as well. Using such data, and known aircraft manufacturing dates, it is possible to triangulate a little and estimate the range of numbers which might fit our airframe. For instance, wartime photographs of A6M3 Model 32 s/n 3030 reveal that it wore HKK number 872. Since s/n 3145 rolled off Mitsubishi’s assembly line 115 units later than 3030, it almost certainly had a significantly higher HKK number. Noted IJN authority, the late Jim Lansdale, believed that 3145’s HKK number was in the high 900s. For whatever reason, John Sterling settled on 994 when he began restoring the Zero, a number which the restored airframe currently wears.

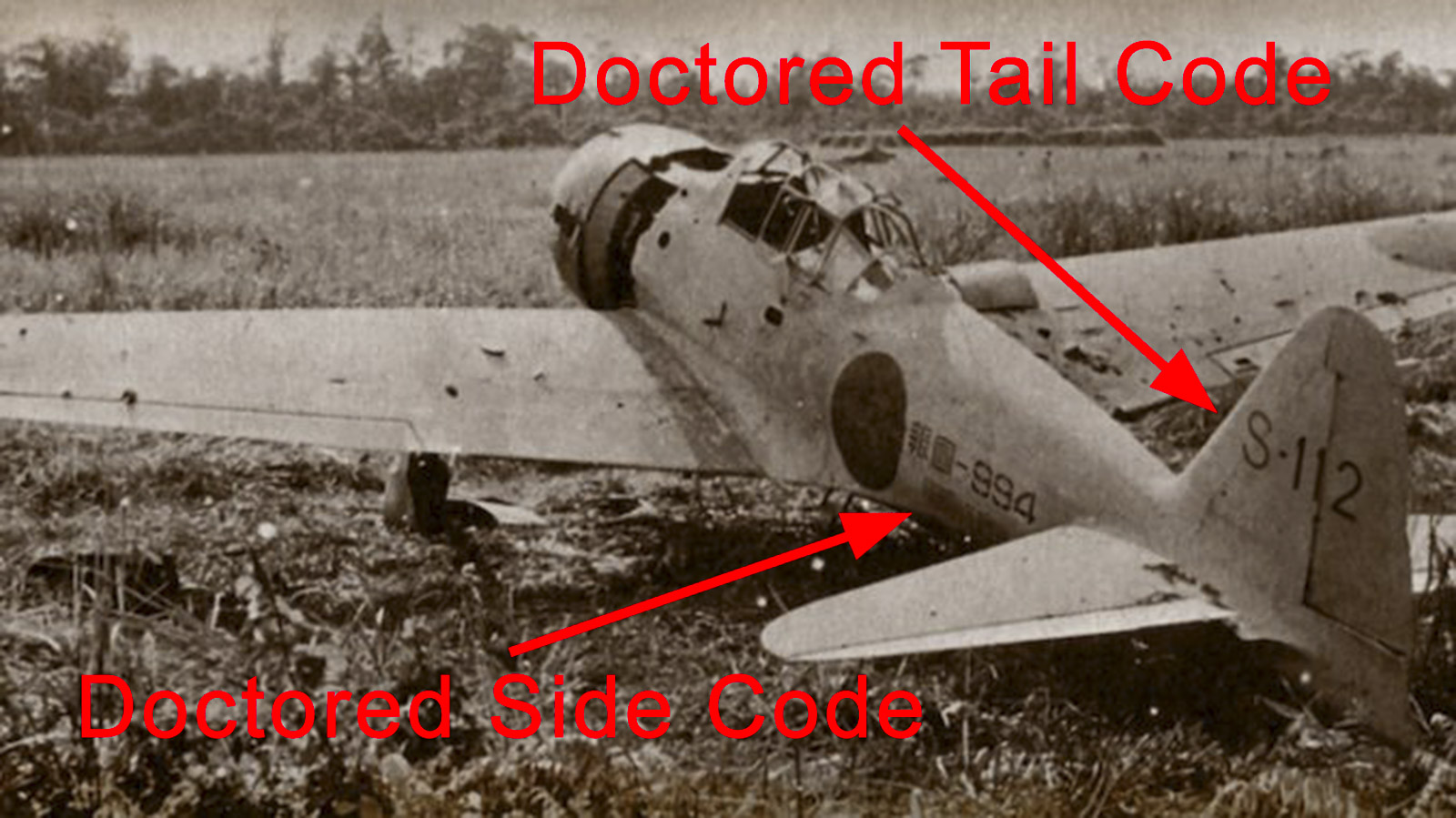

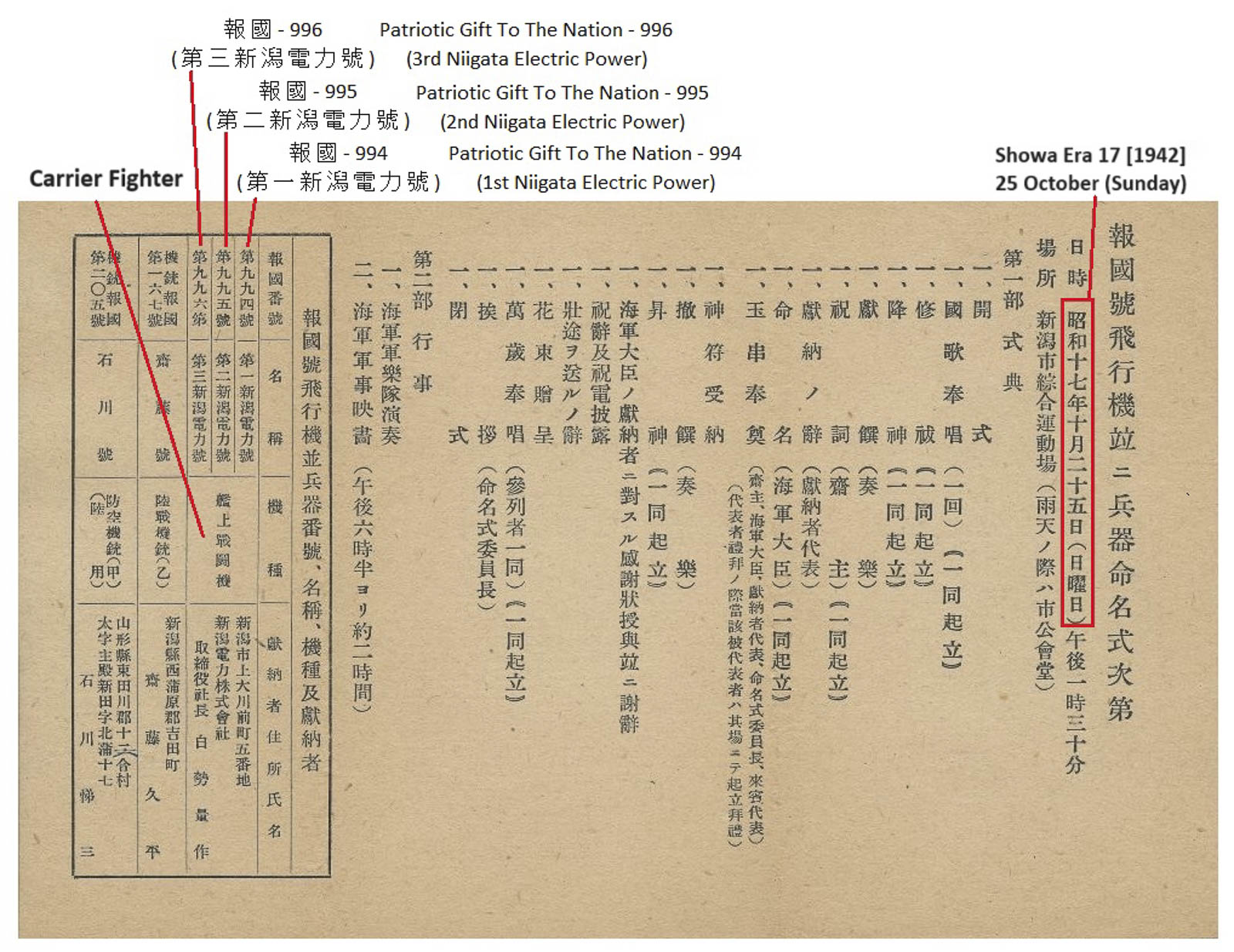

About a dozen years ago, a ‘photograph’ turned up which purportedly showed a wartime image of 994 sporting the Manchukuo Secondary School sponsorship script. That image initially gained a lot of credence, but we now know that it was a fake – doctored, ironically, from an authentic U.S. Army photograph of HKK 872. Even so, it wasn’t until relatively recently that we received definitive proof showing that 3145 could not have been HKK 994. This proof came in the form of original Japanese wartime documents, sourced by Ed DeKiep, showing that HKK 994 (along with 995 and 996) was sponsored by the Niigata Electric Power Company. Several IJN photographs corroborate this discovery as well.

Astonishingly, genuine wartime photographs of a Zero sponsored by the Manchukuo Secondary School system did indeed turn up, part of a small collection owned by noted civil and revolutionary war artist Don Troiani. Graciously, Troiani sent us high resolution copies of these two images which each depict a Japanese pilot standing beside the rear fuselage of the Zero. Given the spacing of the numerals in the image, the HKK number clearly has only three digits. Tantalizingly, however, the pilot in each photograph obscures the middle digit. Even so, the images do at least reveal that the first digit is a “9” while the third digit is a “0”. Current thinking suggests that the complete number is 990, but we likely won’t know for sure until other evidence arrives. Thanks again to Ed DeKiep, we have at least eliminated 980 from the list of possibilities, as the Yamaguchi Prefecture Industrial Association sponsored that airframe. The hunt is also on to identify the two Japanese pilots depicted in these images as well… if anyone out there can help, we would be very grateful!

Confirmation around the HKK numbers is a keen area of interest for us right now, as we near the completion of the restoration work. Making sure the markings are correct is something we always endeavor to do with aircraft in the collection. More articles will follow and we look forwards to sharing the information as it arrives.

Several people helped greatly with the research in this article. Indeed, without Ryan Toews, whose assistance in providing advice, contacts, documents, and photographs we would still be at sea. We also wish to thank Ed DeKiep, Don Troiani, ‘Voytek Kubacki’ and the late Jim Lansdale for their help as well.

To see progress on some of the other restoration projects at the Military Aviation Museum, please click HERE. Or sign up for the monthly From the Workshop newsletter HERE.