Among the 12,000+ Corsairs produced over its eleven-year production run, it is not surprising that the first variant, the F4U-1, is the rarest and most venerable variant. Of the 700+ examples of the “Birdcage Corsair” just four have survived to the present day. One such early aircraft, Bureau Number (BuNo) 02465, is currently nearing the end of a 14-year restoration at the National Naval Aviation Museum (NNAM) in Pensacola, Florida. We last covered this restoration in 2017.

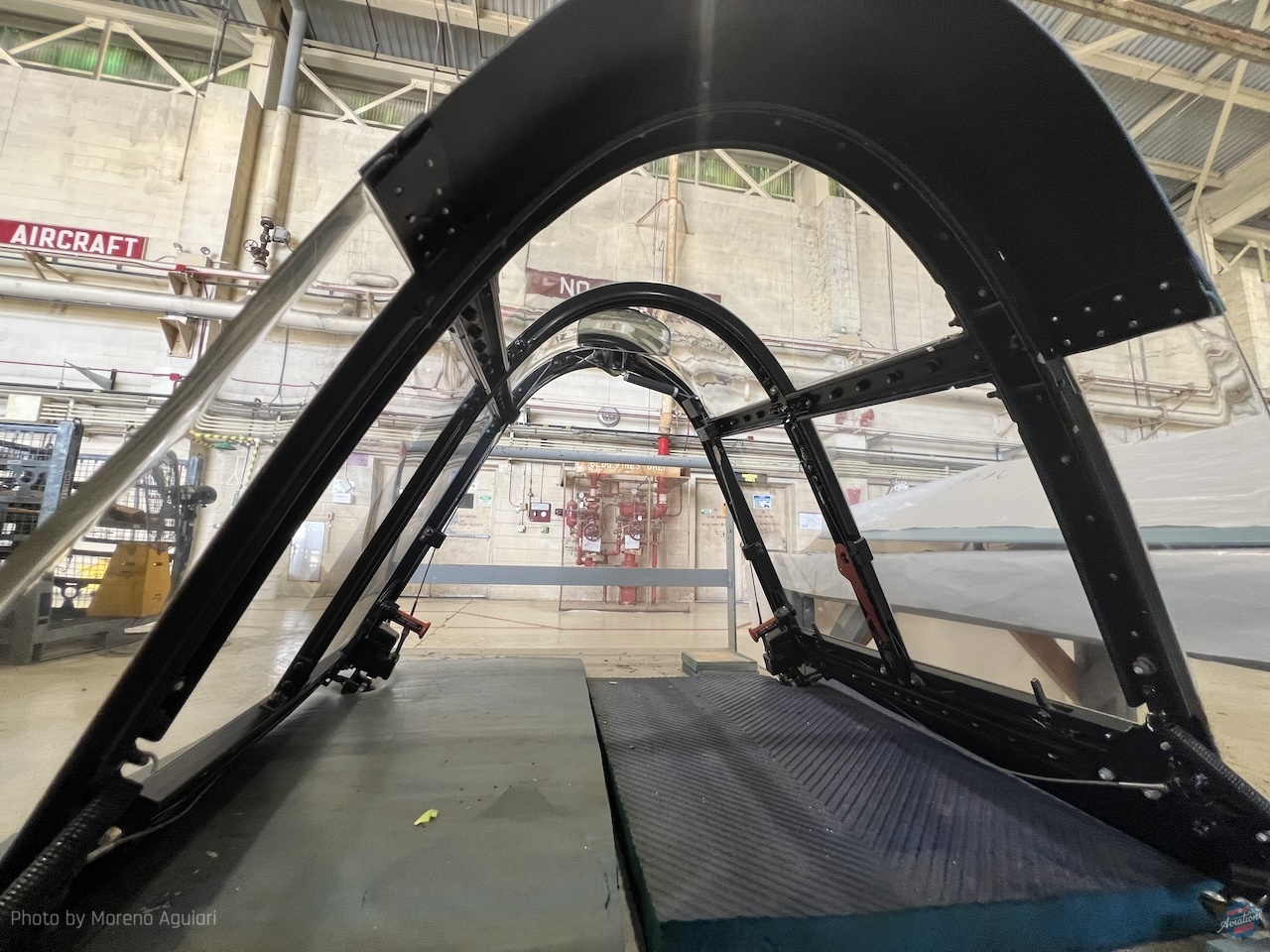

The “Birdcage” nickname refers to the early production models of the distinctive fighter aircraft, distinguished by the intricate framework of their canopy design, which resembled the bars of a birdcage. This early canopy limited visibility for the pilot, leading to later models adopting a more streamlined, blown canopy for improved situational awareness.

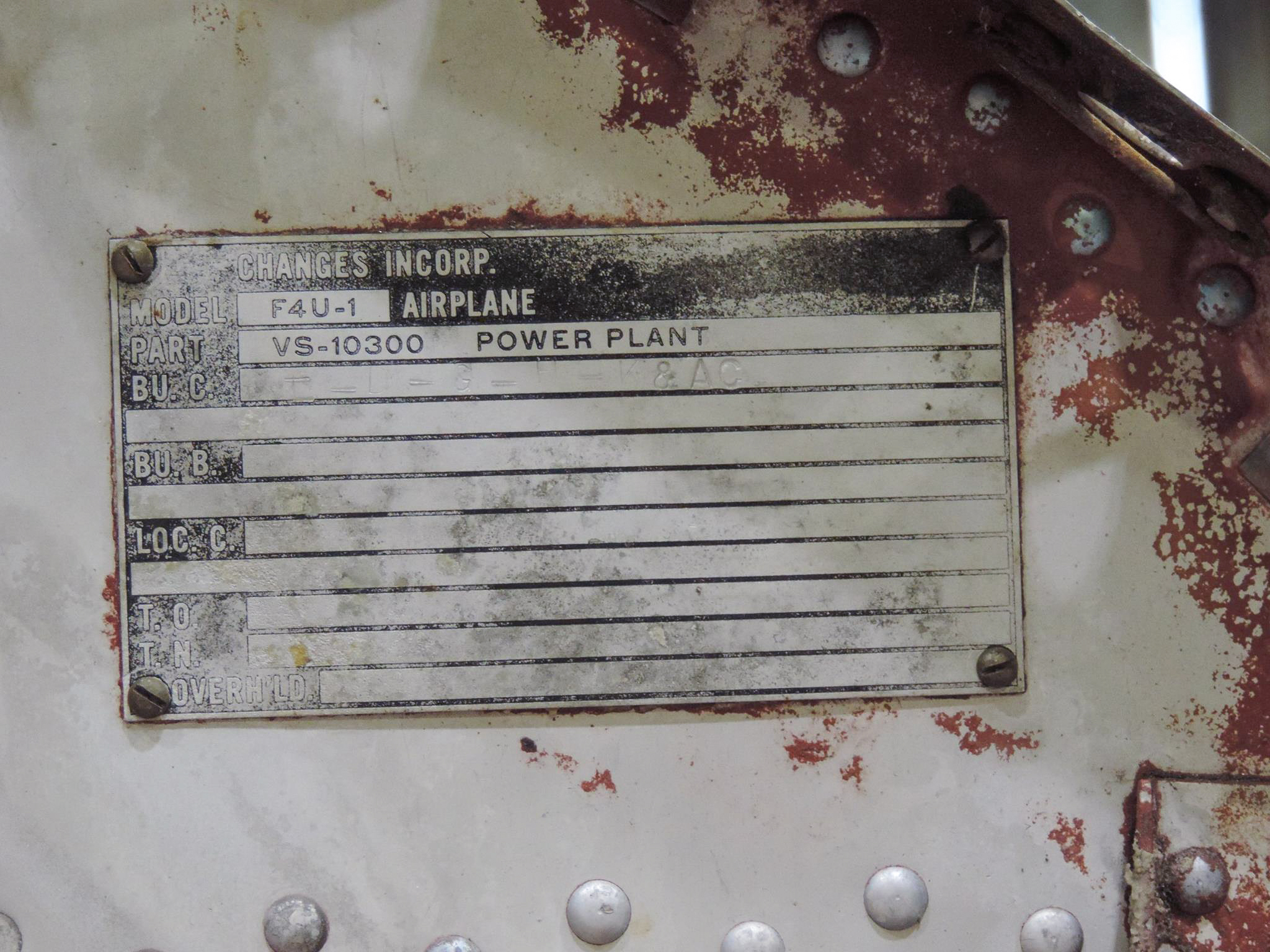

This Corsair can lay claim to being one of the oldest existing examples of the breed in the world, but the story of how it got to Pensacola is a very interesting one indeed. Produced in Vought’s Stratford, Connecticut production facility, 02465 was just the 312th airframe built and was accepted by the US Navy on March 29, 1943. It was assigned fuselage code ‘F-21’ and sent to the Carrier Qualification Training Unit (CQTU) at Naval Air Station (NAS) Glenview, near Chicago, Illinois. The CQTU utilized two paddlewheel steamships converted into the aircraft carriers USS Wolverine (IX-64) and USS Sable (IX-81). To become carrier-qualified, pilots were required to make at least eight carrier takeoffs and landings. On June 12, 1943, Massachusetts-native Ensign Carl Harold Johnson took off from Glenview in 02465/F-21 and headed out over Lake Michigan where Wolverine awaited. At this point in his career, Ens. Johnson had just 388.5 hours total time, 57 of which were in Corsairs.

After a short flight, Johnson entered the pattern for his first approach. Standing on the port side of the deck adjacent to the arresting wires was the Landing Signal Officer (LSO), who carefully observed Johnson’s approach. Just as Johnson crossed over the edge of the flight deck, the LSO gave the “cut” signal, but with his view of the LSO blocked by the nose and wings of the Corsair, Johnson decided to wave off and go around for another approach. At that point, however, F-21’s wheels had hit the deck and Johnson instinctively pushed the throttle forward and fully expected to launch back into the air. Instead, he felt his arresting hook snag the number six wire, but the wire snapped. The hook then caught the seven wire, but the hook was ripped from its mount and Johnson and 02465 plunged off the port side of the deck into Lake Michigan. With “crash boats” on hand, Ens. Johnson was immediately pulled from the water, with minor lacerations. The Corsair on the other hand quickly slipped beneath the waves, presumably forever.

Just four days later, though, on June 16th, 1943, Ens. Johnson completed his carrier qualifications in an SNJ-4 and was assigned to Fighting Squadron 10 (VF-10), Grim Reapers. By that point in the war, VF-10 had completed a combat tour aboard USS Enterprise (CV-6), flying missions during the Battle of Guadalcanal and the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, but were undergoing conversion to the Grumman F6F-3 Hellcat in Hawaii. On November 25th, 1943, Thanksgiving Day, Johnson was involved in a fatal mid-air with another Hellcat while on a training mission over Maui. Today, Ens. Carl H. Johnson is interred at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii.

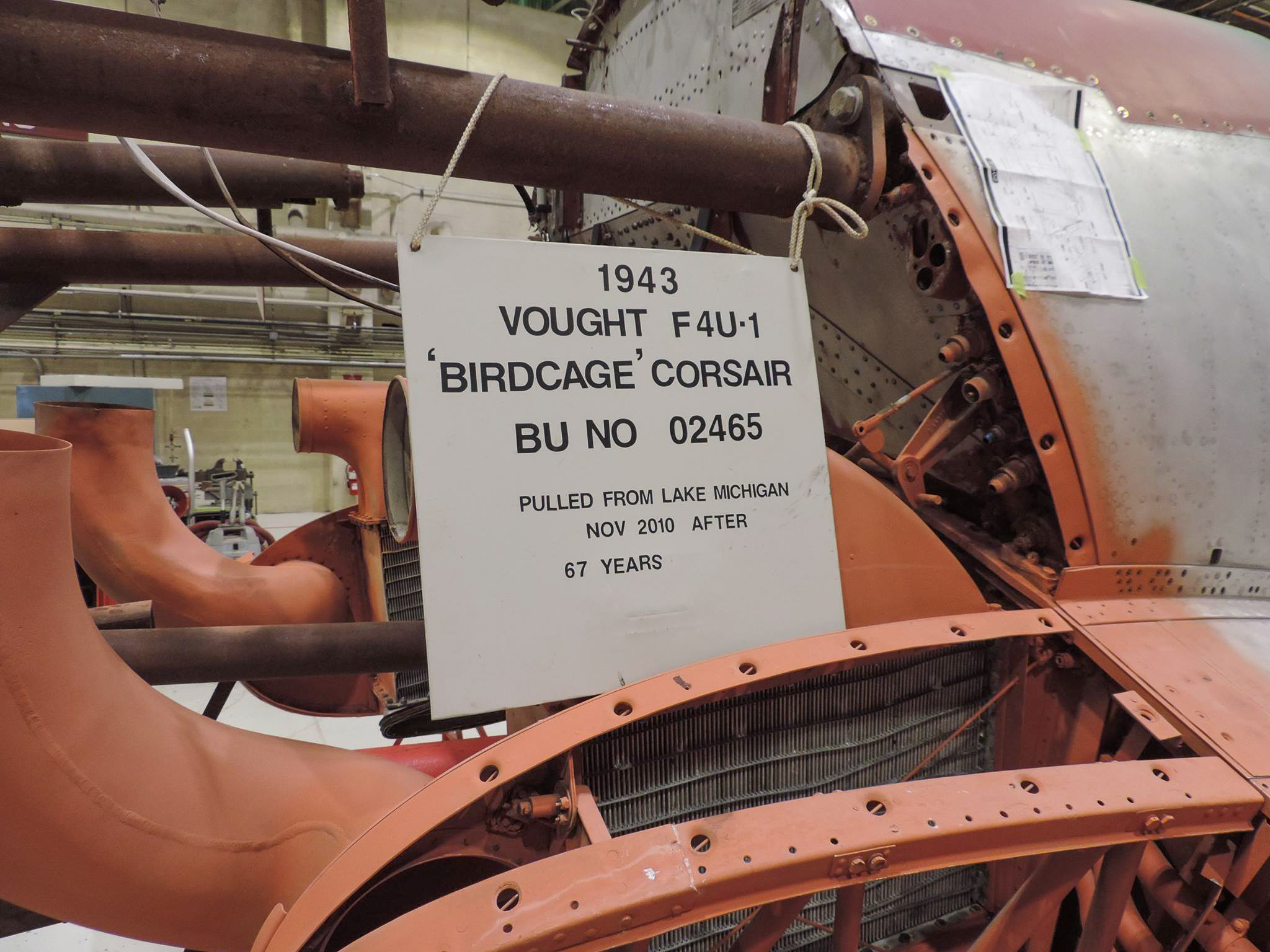

Since the 1980s A&T Recovery, founded by divers Allan Olson and Taras Lyssenko, has worked in collaboration with the Naval History and Heritage Command and NNAM to recover dozens of World War II aircraft from Lake Michigan. Like many of their previous recoveries, the resting place of 02465 was discovered by a side-scanning sonar sweep in early 1995. However, the NNAM would often seek benefactors interested in helping to shoulder the recovery costs, and during the 2000s and 2010s, one such benefactor was pilot and aircraft restorer Chuck Greenhill, and it was he who funded the recovery of 02465.

When A&T commenced the recovery, divers placed inflatable lift bags at strategic points on the two sections to raise them to just below the surface, thus preventing damage during the twelve hours it took to tow the wreckage to the local marina. When the fighter emerged from the water for the first time in 67 years, mussels were scraped and hosed off the airframe, after which it was disassembled and transported to the NNAM’s restoration shop in Pensacola.

The Department Head of Aircraft Preservation and Maintenance at the NNAM, Michael Allen was able to provide valuable insight into what it has taken to restore the Birdcage Corsair recovered from the bottom of Lake Michigan:

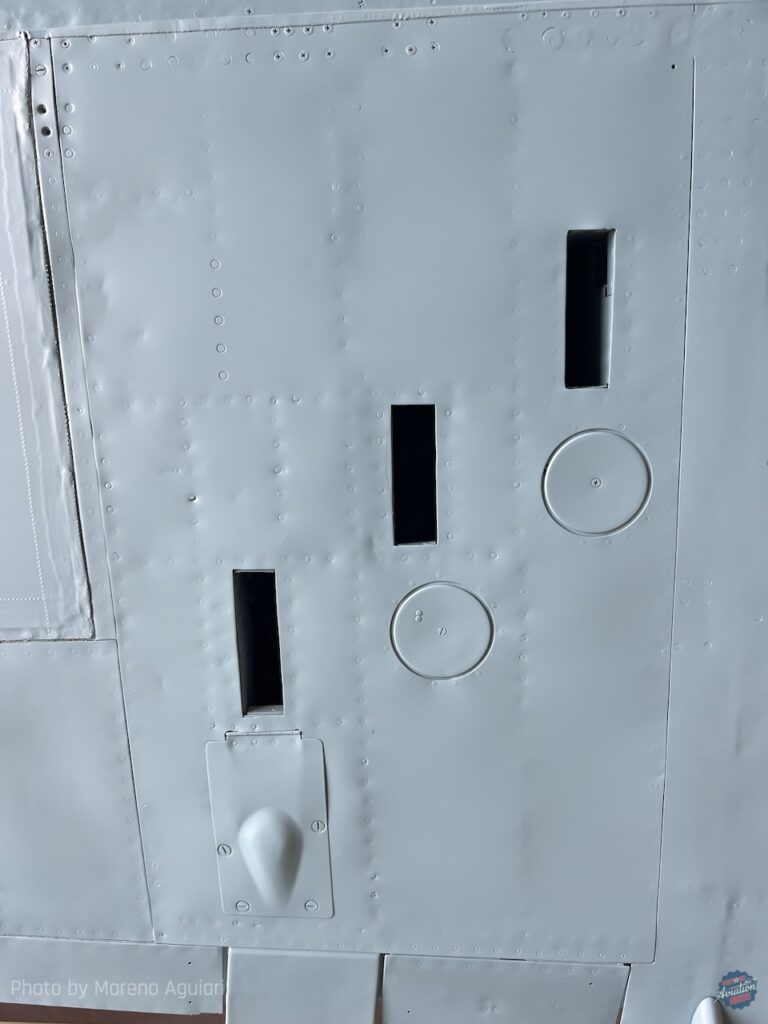

“The tail assembly was likely the most challenging, although when extracting an aircraft from the water, the WHOLE plane wasn’t exactly a cakewalk. We utilized Vought drawings and in some cases where they were non-existent, reverse engineer — a term not unknown to the restoration community. All the skins forward of the radio compartment aft bulkhead are original to the aircraft, save for the speed ring. In some photos, you’ll notice wrinkling of the aft cowl on the port side: we felt it was more important to preserve the original skin rather than manufacture new ones for aesthetic purposes. We were able to use approximately 70% of the original skins aft of that bulkhead, for due to the crash or secondary damage, even though those skins came out of the water, they were too badly damaged to re-use. A few flush patches here and there are incorporated into the horizontal stabs, but the vertical was untouched except for the radio mast. We had to do some welding on that. The rudder and elevators both had some internal work done to the ribs prior to re-covering the surfaces, but not much. They were also in good shape. It seems as though the paints used when it was originally painted had some effect on minimizing corrosion.

“The fuselage tip cap is original to the aircraft as well. We had to patch the LE [leading edge] of the [starboard] wing with about a 24″ repair by insertion. We speculate that the fuel cap retained the pressure inside the wing as it was supposed to and the water depth crushed the LE. The same didn’t happen on the port side. Using Vought drawings, some of the tail wheel struts were manufactured in-house in our machine shop, for the funding was not available to purchase the exceedingly difficult-to-find components. The yoke is original. The canopy is original to the aircraft except for one pane, [the] rest was polished and restored. The aircraft is currently being repainted in the markings it went into Lake Michigan with; Navy blue-grey over light grey and markings in six positions. The prop is yet to be installed or the outer wing panels. Very little script work will be put back on the plane for photography, for whatever reason, shows only a few were on the plane.”

In terms of the museum’s future display plans for the aircraft, Allen elaborated further: “As for the display, we ALWAYS have to move aircraft around on the Museum floor to make room for additions, and this one will be no exception. We will move several airframes around, push the plane onto the spot selected by our Director, and then reposition the aircraft back to mostly original locations. We try to keep the displays somewhat dynamic.”

For the past fourteen years, volunteers have steadily and meticulously disassembled, cleaned, and restored each component of the aircraft. In the past few months, crews have repainted the fighter in the same paint scheme, Non-specular Medium Blue Gray (FS35189) and Light Gray (FS36495), it wore when it plunged into Lake Michigan on that summer afternoon in 1943. Museum officials expect the Corsair will be completed later this summer, and when it is, it will join two of its younger siblings, FG-1D BuNo 92246 and F4U-4 BuNo 97349, on the museum floor.

In addition to BuNo 02465, two more Birdcage Corsairs are under restoration. One is BuNo 02270, which was forced to land in shallow water on Efate Island (now part of the island nation of Vanuatu) on May 5th, 1944, and is now under restoration to be capable of airworthiness at the Classic Jets Fighter Museum at Parafield Airport, near Adelaide, Australia. Another Birdcage Corsair under restoration is BuNo 02449, recovered from Espiritu Santo (also in Vanuatu) and is currently under restoration to flying condition at Vulture’s Row Aviation in Cameron Park, California. We have covered both Birdcage restorations in previous installments, and will provide future updates when they become available. In the meantime, we are eager to see the NNAM complete its restoration of Corsair 02465, and for the aircraft to serve as a permanent memorial to the sacrifices of naval aviators such as Ensign Carl H. Johnson.

Great restoration by Mike Allen and crew on her. I was there as she was being primed. It is part of our history at Ct Air & Space Center in Stratford where all of the Birdcages were built.

Hey Mike! We actually asked Jerry just yesterday to update us on the latest developments with you Corsair!

Vought didn’t produce all of the Corsairs, instead, Vought, Goodyear, and Brewster combined to build over 13,000 Corsairs.