By Matthew Scales

Since the inception of the US Military, rivalries have existed among the different services. From jokes and the belief that one service is superior to the other, to serious disagreements between service leaders over missions and budgets, competition between the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps has always been a part of military service. While services may have their differences from time to time, when a fellow American is in trouble, service affiliations disappear, and the welfare of a fellow countryman becomes a unifying force. One of the greatest examples of this attitude was demonstrated by Navy and Air Force personnel on a day in late May 1967.

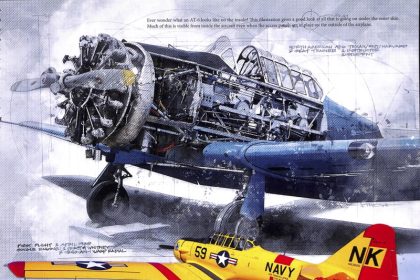

Wednesday, May 31, 1967, dawned as a typical day in Southeast Asia during the Vietnam War. Throughout the region, aircraft from across the US military were preparing for a variety of missions against North Vietnam. At Udorn Air Base in northern Thailand, two F-104 Starfighters from the 435th Tactical Fighter Squadron, call signs Falstaff 21 and Falstaff 22, were prepared to take off on their mission to provide top cover to an RC-130 Commando Lance flying over the Tonkin Gulf.1 Meanwhile, at U-Tapao Air Base, Air Force KC-135 maintenance personnel were busy installing a Boom Drogue Adapter (BDA) on the aircraft’s refueling boom. The adapter would be a necessary modification to the aircraft for its mission that day of refueling the F-104s, as the Starfighters were one of the few Air Force fighters whose design used the same refueling system as Navy aircraft.2 As the maintainers installed the unusual piece of equipment, no one could have known the historic and lifesaving effect the ten-foot hose and basket would have later that day.

While maintenance personnel completed their work, Major John Casteel, along with his co-pilot Captain Dick Trail, navigator Captain Dean Hoar, and boom operator Master Sergeant Nathan Campbell, prepared for their unusually long flight. While typical tanker missions from U-Tapao would involve flying over South Vietnam or refueling tracks over the Tonkin Gulf before returning to Thailand, on this day, the crew of the KC-135 was preparing to return to the United States.3 Their flight would take them from U-Tapao to a refueling track off the east coast of North Vietnam, where they would rendezvous with the F-104s before turning east and flying to Kadena Air Base, Okinawa. From there, they would begin their trip across the Pacific back to their home base of Clinton-Sherman Air Force Base in Oklahoma. The unusual flight also meant the KC-135 would be carrying fourteen passengers, including two additional four-man KC-135 crews.4 The tanker’s long flight necessitated adding a larger fuel load to the aircraft than would normally be required for a short refueling mission over South Vietnam, yet another factor that would prove invaluable later in the day. Their passengers and fuel loaded, the large tanker, call sign Brown Anchor 21, lifted into the sky at 0615.5

As Air Force personnel prepared for their missions, some six hundred miles away in the Tonkin Gulf, aircraft from the USS Bon Homme Richard’s CVW-21 prepared for an alpha strike against North Vietnam’s Kep Airfield. Attacked and put out of service earlier in the month, the strike, ordered by Rear Admiral Vincent de Poix, was considered a “harassment strike.” Led by six A-4s from VA-76, the attack on the airfield thirty-seven miles northeast of Hanoi was also comprised of two Skyhawks from VA-212 flying anti-radar suppression and four A-4s from the Rampant Raiders providing flak suppression for the strike package. Among these four flak suppressors was Lieutenant Commander Arv Chauncy with Ensign Steve Gray flying as his wingman.6 The Skyhawks, along with F-8s from VF-24 and VF-211, A-1 Skyraiders from the Barn Owls of VA-215, and all three A-3 refueling tankers from Detachment L of VAH-4, began launching from the Bon Homme Richard at 0849.7

As Bonnie Dick was launching her aircraft, the crew of Brown Anchor 21 winged their way over South Vietnam. As the tanker passed near Danang, Maj. Casteel and Capt. Trail casually remarked to each other that both of the runways at Danang Air Base were operational that day, an unusual event for a base that had begun to experience more frequent attacks.8 Maj. Casteel then turned his aircraft north and set up in his race track pattern as MSgt. Campbell prepared to refuel the two F-104s. Having already tanked on a KC-135 being relieved by Casteel’s crew, the fighters were scheduled to receive three offloads from Brown Anchor 21 before returning to Thailand.

Over the Tonkin Gulf, aircraft of Air Wing 21 rendezvoused and began their flight towards Kep Airfield. In an effort to avoid more heavily defended areas, the formation flew north of the airfield, paralleling the North Vietnam/China border before turning southwest towards their target. As the formation approached the airfield, they came under intense anti-aircraft fire. Among the first to be hit was LCDR Arv Chauncey, whose A-4 took hits that destroyed his engine. Gliding as far as he could, LCDR Chauncey was finally forced to eject from his crippled Skyhawk. Observing a good chute and making radio contact with his wingman, ENS Gray immediately began coordinating a rescue effort for Chauncey. Quickly joining the effort, fellow Rampant Raiders CDR Marvin Quaid and LTJG Mark Daniels joined up on Gray with Daniels acting as a radio relay for Gray, who was flying low over the mountains to keep Chauncey in sight. Quickly running low on fuel, Gray and Quaid were forced to turn the rescue command over to the Barn Owls of VA-215 and return to the Bonnie Dick.9 While Gray and Quaid returned to the carrier, the attempt to rescue a fellow American from enemy territory was only beginning. While ENS Gray had immediately called for a rescue helicopter before LCDR Chauncey even hit the ground, the response was delayed. Inaccurate intelligence of North Vietnamese MiG activity in the area provided to Admiral de Poix caused him to delay the helicopter for the rescue.10 To counter this reported threat, as well as to replace aircraft too damaged during the attack to continue supporting the effort, the Bon Homme Richard launched a four-ship RESCAP of F-8s from VF-24.11 While LCDR Chauncey had been the only member of Air Wing 21 to have been shot down during the attack on Kep, many aircraft in the strike group had been badly damaged, causing their aircraft to rapidly lose fuel. Having refueled the strike package prior to the attack and then providing fuel for the multiple aircraft damaged in the attack, the A-3s led by CDR John Wunsch from VAH-4 quickly realized that they too would need refueling support.

Southwest of the Navy tankers, MSgt. Campbell had just provided the first refueling for the Falstaff flight when Maj. Casteel and Capt. Trail heard two near-simultaneous radio calls from Water Boy, a radar site at Dong Ha, as well as CDR Wunsch on Guard, both requesting emergency refueling support for two Navy tankers flying just south of Haiphong Harbor.12 Understanding the urgency of the situation, Maj. Casteel immediately headed north and prepared to help in any way he could. As the crew flew north to refuel the Navy aircraft, they had to figure out how to do something none of them had ever done- refuel Navy aircraft. The two services’ unfamiliarity with each other showed immediately. As the two pilots started coordinating their rendezvous, Maj. Casteel told CDR Wunsch he was at 28,000 feet. Wunsch replied that his A-3s’ fuel states were so low that they would be unable to climb to that altitude. Making an emergency descent, Maj. Casteel brought his KC-135 to 5,000 feet and began attempting to locate the Navy tankers.13 Having never flown with Navy aircraft before, one of the first challenges faced by the crew was how the aircraft would find each other. Casteel later joked, “We were too low to receive help from our radar sites, and I doubt if the North Vietnamese were interested in offering assistance.” Tuning the frequency of a TACAN provided by Red Crown, the KC-135 flew to the ship and began circling the destroyer. When the A-3s arrived, they were unable to locate the Air Force tanker, so CDR Wunsch told Casteel to roll out of his turn onto a heading that would put him flying towards Haiphong Harbor. When Casteel informed the A-3 pilot he had to turn, Wunsch replied, “If you turn now, I’ll run out of gas before I can get to you.”14 Agreeing to roll out, Casteel pointed the Air Force tanker towards the coast of North Vietnam. Casteel remembered later, “I told him (Navigator Dean Hoar) when he could stand it no longer, he should tell me and we would turn.” He continued, “As the nose of my aircraft began to cover the mouth of Haiphong Harbor, the Navy tanker said ‘turn’ about the same time Dean said turn.”15

Finally making the rendezvous, the lessons continued. With a more critical fuel state, Wunsch approached the boom first.16 As the KC-135 co-pilot, Capt. Dick Trail operated the tanker’s refueling system and turned on two of the tanker’s four pumps, the setting used by the Air Force’s version of the A-3, the B-66 Destroyer.17 He quickly learned the pressure was too great when it pushed Wunsch out of the KC-135’s refueling basket. The pressure lowered to one pump, Wunsch again made contact and took a quick 2,300 pounds of fuel before moving to the tanker’s right wing to allow his wingman, LCDR Don Alberg flying A-3 call sign Hollygreen 898, to fill his tanks.18 As the fuel flowed into his nearly empty tanks, the four F-8s from VF-24 called in, saying they too were critically low on fuel, and one in particular was so low that he would embody the saying “desperate times call for desperate measures.” Approaching the A-3s in formation with the Air Force tanker, the four-ship RESCAP from VF-24 needed gas urgently. Hearing their desperate situation, LCDR Alberg told his bombardier navigator to deploy their aircraft’s refueling hose because, as he would remark later, “I knew we could take fuel from the KC-135 faster than we could give it to a receiver.”19 Behind the unusual formation, LT Chip Harris, so low on fuel he was concerned with having to eject from his F-8, saw the refueling hose deploy from the Skywarrior and immediately plugged his Crusader’s refueling probe in the A-3’s basket.20 Grateful to be receiving fuel, Harris didn’t think about the fact that he had just completed the first known “trilevel” refueling. Concerned with the confusing radio traffic he was hearing, Maj. Casteel asked, “What’s going on back there?” The answer came from one of the F-104 pilots who had stayed with the big tanker as it headed north: observing the A-3 plugged into the KC-135’s basket with an F-8 plugged into the Skywarrior, the Air Force pilot replied, “You’ve got a daisy chain going on.”21

Having received enough fuel to return to the Bonnie Dick, LT Harris immediately turned his F-8 back to the carrier before being recalled by the flight lead, CDR Red Isaacks.22 The rest of the RESCAP (LCDR John Bartocci and LCDR Chuck Blaker) then refueled from the A-3s before returning to the Bon Homme Richard. Now too low on fuel to make it to Kadena, the KC-135 headed south with its F-104 escort, now grateful that they had heard that both runways at Danang were open. The tanker’s interaction with the Navy wasn’t over, however. Having also launched in support of the rescue effort of LCDR Chauncey (and later LTJG Mark Daniels, who was rescued), two F-4s from the “World Famous Pukin’ Dogs” of VF-143 called up also needing gas to get back to their ship, the USS Constellation. Still glad to help and with fuel to give, the tanker gave each Taproom F-4 3,000 pounds, saving Phantoms flown by LCDR Pat Thompson with his RIO LTJG Ed Barczak, along with his wingman ENS Barry Miller with his RIO ENS Davy Jones.23 With no other aircraft in need of fuel, the KC-135 landed at Danang, quickly refueled, and proceeded to Kadena to face the music for what they had done.

Stories conflict as to the potential consequences the Air Force crew faced for their actions that day. Dick Trail remembered continuing their flight to Guam, where they were debriefed by Major General William Crumm, the commander of the 3rd Air Division, responsible for all Strategic Air Command (SAC) assets in the Pacific (B-52s and KC-135s). Trail recalled Crumm asking them for details about the refueling before telling them a story of a young Major Crumm who had broken a rule as a B-29 pilot to ensure a particular bombing mission to Japan was successful. Casteel, as the aircraft commander, remembered the uncertainty of his fate lasting well into the crew’s return to Oklahoma.24 After much discussion, Casteel remembered his actions, which appeared to be heading towards a court-martial. The crew of the KC-135 had broken a number of rules. Not only had the Boeing tanker flown much further north than they were allowed to, but the refueling took place a mere twenty miles off the coast of North Vietnam. Additionally, Casteel had flown his aircraft that far north to refuel Navy aircraft at a time when, according to Trail and Casteel, Air Force tankers were forbidden by SAC regulations from refueling Navy aircraft without permission.25 To top it all off, after the event, the crew had landed their large aircraft in South Vietnam, a move that, though all but forbidden, ultimately may have helped save the careers of the crew. While maintenance personnel at the base refueled the KC-135 and Major Casteel reported to Air Force officials the fact that they had diverted, a passenger aboard the tanker and a KC-135 pilot himself, 1Lt. Gary Leuders mentioned to a Marine pilot why the tanker had landed at the base. According to Leuders, the Marine then got word to Admiral de Poix about the fact that the Air Force tanker had saved a large number of Navy aircraft.26 Months later, Major Casteel remembered discussions over his actions abruptly stopped when General John McConnell, Chief of Staff of the Air Force, reportedly received a phone call from then Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral David L. McDonald. McDonald, himself a Naval Aviator, reportedly told McConnell, “If you court-martial those guys, I’ll pin the Navy Cross on their chest.”27

In the end, all four crew members of Brown Anchor 21 received the Distinguished Flying Cross and, in 1968, were awarded the Mackay Trophy for the most meritorious flight of the year. Despite a valiant effort from aviators from both the Bon Homme Richard and the Constellation, Arv Chauncey was captured and endured 2,105 days of captivity before his release on March 4, 1973. When asked about that day, individuals involved in the unique event respond in different ways. Steve Gray, who later documented his experiences in his book “Rampant Raider,” described May 31, 1967, as “the worst day of my life.”28 In a speech to the 1968 graduating class of Allan Hancock College in Santa Maria, California, John Casteel said of the day, “I’ve heard a lot of distress calls from other pilots. It’s a pretty useless feeling because there isn’t anything you can do to help. This time it was different.”29 Similarly, Don Alberg knew Chip Harris needed fuel and simply deployed his refueling hose to help a fellow Naval Aviator. Chip Harris joked that he didn’t do anything special and, if anything, was foolish to allow his Crusader to get as low on fuel as it had.30 In a war filled with stories of loss and frustration, and on a day that included those emotions for a number of Naval Aviators, another group of individuals were willing to bend rules and try things that had never been done before, and in doing so, proved no matter what color a person’s uniform is, when an American is in trouble, rivalries cease.

| 1 13th Air Force Form 26 “Historical Data Record,” 435th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 1 Jan 1967- 30 Jun 1967. 2 AFTO 781, KC-135A 60-0329, 379th Organizational Maintenance Squadron, May 31, 1967; History from PACAF; Charles K. Hopkins, Headquarters, Strategic Air Command, SAC Tanker Operations in the Southeast Asia War, (Office of the Historian, Headquarters Strategic Air Command, 1979), 69. 3 Discussion with Dick Trail, December 6, 2016. 4 Email, Gary Leuders to Matt Scales, “Trilevel Refueling,” December 17, 2016. 5 AFTO 781, KC-135A 60-0329, 379th Organizational Maintenance Squadron, May 31, 1967; Report, 3rd Air Division, Anderson AFB, Guam, to Commander, Strategic Air Command, “Emergency Navy Air Refueling in Gulf of Tonkin,” June 2, 1967. 6 Stephen Gray, Rampant Raider: An A-4 Skyhawk Pilot in Vietnam, (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2007), 228-229; Cruise Book, USS Bon Homme Richard, 1967. 7 NAVPERS 3100/2, Deck Log- Remarks Sheet, USS Bon Homme Richard, May 31, 1967, pg. 1. 8 Email, John Casteel to Matt Scales, “RE: F-104 Question,” February 10, 2017. 9 Stephen Gray, Rampant Raider: An A-4 Skyhawk Pilot in Vietnam, (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2007), 230-234. 10 Ibid, 231-232; Email, Stephen Gray to Matt Scales, “RE: Question,” January 15, 2017. 11 Discussion with Chip Harris, January 9, 2017; Aviator’s Flight Log Book, LCDR Chuck Blaker, May 31, 1967. 12 Email, Dick Trail to Matt Scales, “RE: F-104 Question,” February 10, 2017; Report, 3rd Air Division, Anderson AFB, Guam, to Commander, Strategic Air Command, “Emergency Navy Air Refueling in Gulf of Tonkin,” June 2, 1967. 13 Email, Dick Trail to Matt Scales, “RE: F-104 Question,” February 10, 2017. 14 Lt. Col. John H. Casteel, “Commencement Speech, Allan Hancock College,” (speech, Santa Maria, CA, May 1968). 15 Discussion with John Casteel, December 30, 2016. 16 Discussion with Don Alberg, February 2, 2017. 17 Email, Dick Trail to Matt Scales, “RE: F-104 Question,” February 10, 2017. 18 Charles K. Hopkins, Headquarters, Strategic Air Command, SAC Tanker Operations in the Southeast Asia War, (Office of the Historian, Headquarters Strategic Air Command, 1979), 69. 19 Discussion with Don Alberg, December 21, 2016. 20 Discussion with Chip Harris, January 9, 2017; Aviator’s Flight Log Book, Lt. Chip Harris, May 31, 1967. 21 Discussion with Dick Trail, December 10, 2016. 22 Discussion with Chip Harris, January 9, 2017. 23 Email, Davy Jones to Matt Scales, “RE: Pat Thompson VF-143,” January 26, 2017; Aviator’s Flight Log Book, Ens. Davy Jones, May 31, 1967; History from PACAF; Charles K. Hopkins, Headquarters, Strategic Air Command, SAC Tanker Operations in the Southeast Asia War, (Office of the Historian, Headquarters Strategic Air Command, 1979), 69. 24 Discussion with Dick Trail, December 10, 2016. 25 Email, Dick Trail and John Casteel to Matt Scales, “RE: F-104 Question,” February 13, 2017. 26 Email, Gary Leuders to Matt Scales, “Trilevel refueling,” December 17, 2016. 27 Discussion with Dick Trail, December 10, 2016. 28 Email, Stephen Gray to Matt Scales, “RE: Question,” January 15, 2017. 29 Lt. Col. John H. Casteel, “Commencement Speech, Allan Hancock College,” (speech, Santa Maria, CA, May 1968). 30 Discussion with Chip Harris, January 9, 2017. |