On Independence Day, President Donald Trump signed into law a sweeping 900-page spending bill, dubbed the “One Big Beautiful Bill,” that carries a surprise for space enthusiasts: $85 million earmarked to relocate NASA’s most flown space shuttle, Discovery, from the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum to Space Center Houston, the visitor hub of NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

Buried deep within the legislation is a provision—written in vague legalese—that directs the transfer of a “space vehicle” to a NASA center involved in the Commercial Crew Program, for exhibition within the surrounding metropolitan area. The language, carefully crafted to bypass certain Senate reconciliation rules, effectively enacts the “Bring the Space Shuttle Home Act” put forward earlier this year by Texas Senators Ted Cruz and John Cornyn. “It’s long overdue for Space City to receive the recognition it deserves by bringing the space shuttle Discovery home,” said Cornyn after the bill passed the Senate by a razor-thin margin, with Vice President J.D. Vance casting the tie-breaking vote.

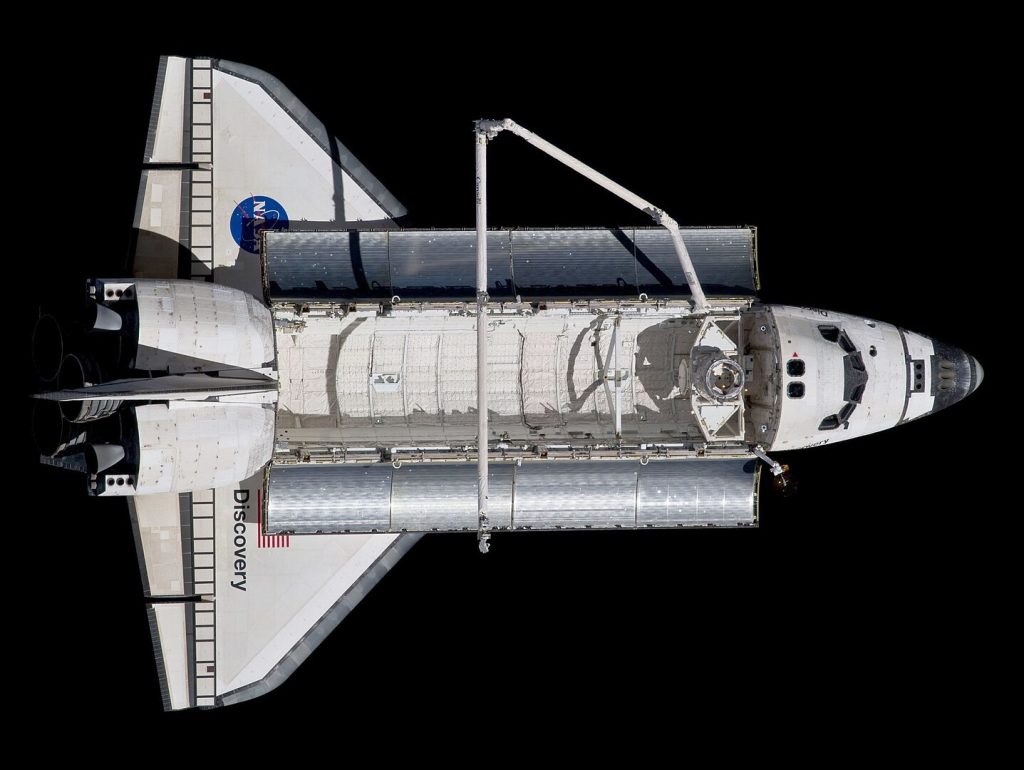

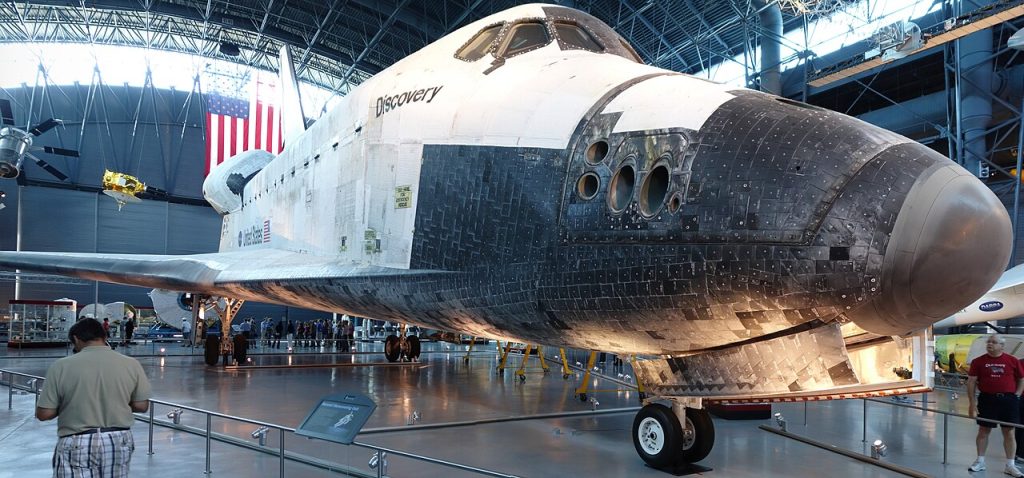

The bill allocates $85 million to execute the move, including no less than $5 million for transportation costs and the remainder for constructing a facility in Houston to house the orbiter. The deadline for completing the transfer is January 4, 2027. Although the legislation doesn’t name Discovery outright, its context and references make it clear which shuttle is being targeted. The Smithsonian’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, has housed Discovery since 2012, preserving it as the most complete example of the space shuttle program. With 39 missions under its belt from 1984 to 2011—including the 2006 “Return to Flight” mission following the Columbia disaster—Discovery holds the record as America’s most flown spacecraft.

“This legislation rightly honors Houston’s legacy as the heart of America’s human spaceflight program,” said Cruz, who chairs the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. “It ensures that any future transfer of a flown, crewed space vehicle prioritizes locations that have played a direct and vital role in U.S. space exploration.” Cruz also emphasized the symbolic value of the transfer: “Bringing such a historic space vehicle to Houston will not only celebrate the city’s indispensable contributions to NASA’s missions, but also serve to inspire the next generation of explorers, scientists, and engineers.”

While supporters in Texas are celebrating the move, the plan raises questions. Space Center Houston has not yet released details on how or where Discovery would be displayed, nor how the move would be executed. Currently, the center exhibits a full-scale shuttle mockup, Independence, mounted atop NASA 905, the original Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft.

Costs are another concern. When the orbiters were first retired and delivered to museums in 2012, preparation and transport alone ran nearly $28.8 million per shuttle, not including display facility construction or local ground transportation. Whether the $85 million allocation will be sufficient remains uncertain. Discovery’s placement at the Smithsonian was originally determined by NASA in 2011 after a competitive review process. A NASA Inspector General investigation later confirmed that there was “no evidence that the White House, politics, or any other outside force improperly influenced the selection decision.”

It is unclear whether the Smithsonian or other stakeholders have legal avenues to oppose the shuttle’s removal. Still, if the plan proceeds, Discovery will embark on one final journey—not to orbit, but to a new role in Space City, Texas, where it may soon become the crown jewel of Houston’s growing space heritage. A group called “Keep the Space Shuttle” has formed with the objective to stop this. They are long-time supporters of the Smithsonian’s who believe that national treasures like Discovery belong to all of us—not just to those who can sneak a clause into a budget bill.

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.

This is obscene. The Smithsonian is the rightful custodian of the nation’s most meaningful artifacts. And recall that Houston left a Saturn V outdoors to dissolve in the heat and humidity for decades (like the shuttle carrier today) before doing any meaningful conservation work. The visitor center at JSC is a privately run entity that’s more interested in entertainment than artifact display and conservation. If they really want a shuttle, take the Enterprise from NY…

I don’t see any point in this.

Texas has no right to try and move Discovery out of her home at the Smithsonian, and relocate her to the Houston Space Center, just because they think that as the home of the Johnson Space Center, they think they can lay claim to the Shuttle, over the Smithsonian. Discovery belongs right she is, and treated as a national treasure, just like all of the other air, and space vehicles owned by the Smithsonian.

So glad you shared the advocacy group I’m joining immediately.

Its such a waste of government money that could be better spent elsewhere. Not only is Discovery the centerpiece of the Udvar Hazy museum its also the most historically significant shuttle out of all the remaining vehicles. Travel is not only exceedingly expensive and costly it also could risk damaging the orbiter and destroying irreplaceable pieces of its history.

The point of a national museum like the Smithsonian is to celebrate and display the nation’s greatest accomplishments in aerospace while preserving these aircraft and their history for future generations. Texas has nowhere to put it, no need for it, and does not draw anywhere near the same number of visitors that the Smithsonian does. Moving Discovery will have absolutely no effect on any of that. It’ll cost millions to move it, house it, and maintain it. Not to mention that the museum in Houston gets a fraction of the funding and support. We’re paying millions to make Discovery harder to see and to give it to caretakers less equipped to care for her.

All of this to “bring the shuttle home” when they weren’t built there, didn’t launch there, didn’t land there, and basically only talked to Houston over the radio. Not to mention the Houston museum already has one of only two shuttle carriers, one of only 3 Saturn V rockets, one of only 6 Apollo Capsules from successful missions to moon’s surface, a Gemini Capsule, a Mercury Capsule, and a full-scale 1-1 mockup of the same vehicle they’re stealing from the Smithsonian. But all that isn’t enough for Texas lawmakers. Most of the bigger artefacts where stored outside or still are stored outside. You can’t convince me a project paid for by the entire country belongs in one out of the way city in Texas instead of a national museum visited by millions from around the world every year.

This sets a terrible precedent too. Imagine if North Carolina or Ohio got into a fight over “bringing the Wright Flyer home”. What if Missouri though they deserved the Spirit of St. Louis more then the Smithsonian? If the museum’s collection can raided and handed off like its a yard sale, what else could be auctioned off to individual states in exchange for votes in the house or senate? The Bell X-1? The X-15? The Apollo 11 Capsule? I’m seriously hoping the Smithsonian Can keep the orbiter.

$80,000,000 to move this, and they don’t even have a plan for what they’d do with it?

Talk about “waste, fraud, and abuse” right?

No.

Every time a senator gets involved in an aviation museum transfer, it turns into a shitshow.

Remember what happened when Senator Norm Coleman flexed his might and transferred an SR-71 to Langley and had it put up on pilings?

Discovery is right where it belongs!

Go to Cancun Cruz!

Doesn’t everyone remember the 2011 bid process of many competing museums all vying for the honor of becoming the caretaker of Discovery? Yeah, Johnson Space Center in Houston was one of those competitors. They go denied, declined, turned down.

Additionally, no Space Shuttles ever launched out of Houston, so WTH is all this “bring her home” malarkey?

Since they couldn’t win being awarded the caretaker of Discovery honor, they’re taking a page from all the non-citizen criminals this sh*t-hole *Armpit of Texas” is infested with, and just unethically STEAL the Discovery space shuttle…sad, but true.

PS: I also, very unfortunately, live in this cesspool along the southern coast of The Gulf of America.

Houston deserves a Shuttle. Just not in an amusement park-like facility that charges admission. And not Discovery, which is an important artifact and belongs right where she is. The Hazy is THE premier aircraft and spacecraft restoration facility, it’s close to the Capitol, and it’s free. If JSC wants a Shuttle, take Enterprise or Endeavour. What involvement did New York City have in the Space Race besides a few ticker tape parades? And LA had a lot of the aerospace contractors that built the Shuttles, but they didn’t fly them… There should be a Shuttle in Florida, one in Texas, and Discovery in Washington DC.

I’m a native Texan, and would love this spacecraft to be sent here. Honestly, given the state of readiness of it’s potential home and the planning for it’s use and care, something is not right. There is obviously a lot of chicanery and underhandedness involved, and considering the cost, my gut instinct just says whoa, put the brakes on here.