I visited the Michael Beetham Conservation Centre (MBCC) at Cosford in late March to see what was currently under restoration and to meet with museum curator Tom Hopkins for an update on the museum’s latest plans. Although I had hoped to visit the storage hangars to view the aircraft held in storage and those listed for disposal, this wasn’t possible on this occasion. The Conservation Centre previously held public open weeks—typically in November—which allowed enthusiasts and the general public to see restoration work in progress. These popular events were discontinued a few years ago, so it was a welcome opportunity to visit the facility again. When the Conservation Centre was last open, the main restoration projects included the Vickers Wellington, Handley Page Hampden, and Dornier Do 17. Since then, the superb Vickers Wellington Mk.X MF628 has been moved to the main display hangars and fully assembled as of April 2023.

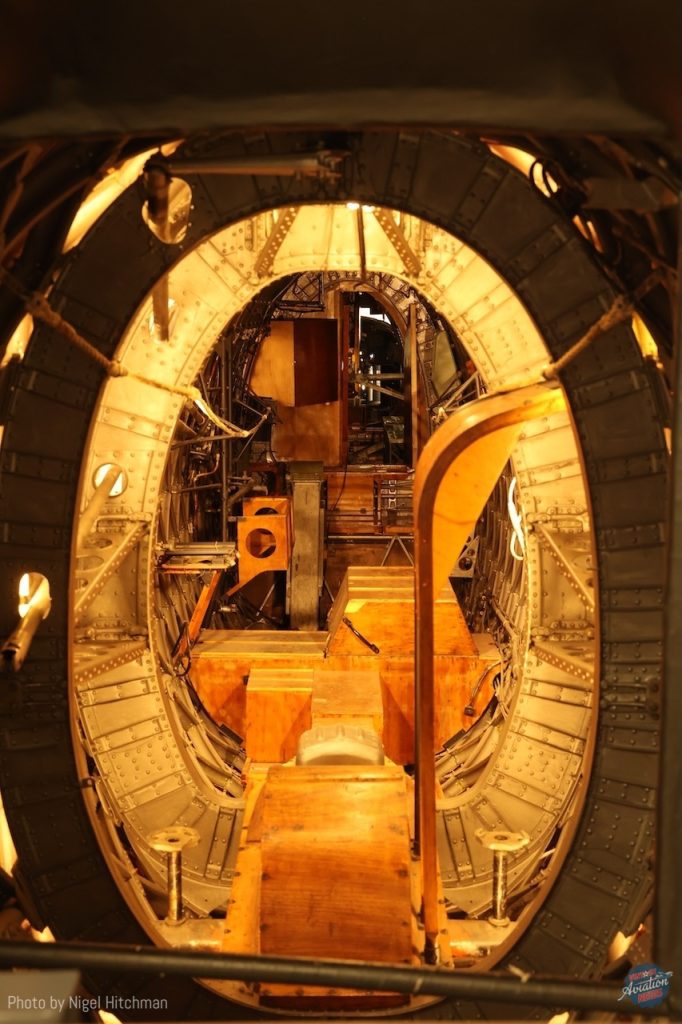

The Handley Page Hampden TB.1 P1344 was one of 32 Hampdens on a ferry flight from Sumburgh in the Shetland Islands to northern Russia in 1942, destined to protect Arctic convoys. It was shot down over the Kola Peninsula in September 1942 by Messerschmitt Bf 109s. Recovered in 1991 and acquired by the RAF Museum in 1992, its restoration has progressed slowly, but more intensively since 2014. It is now ready for display at the RAF Museum in Hendon. The rear fuselage is mostly original, while the forward fuselage has been reconstructed with some original components. The tail boom is a new build, with the damaged original retained for display, and the tailplane is approximately 25% original. Unfortunately, the wings have not been restored and remain in storage.

The Dornier Do 17Z-2 (coded 5K+AR), the only surviving example of the type, was recovered from the Goodwin Sands in Kent in 2013, where it had lain submerged since being shot down in August 1940 by Boulton Paul Defiants. Following a lengthy conservation process—including time in a controlled environment and citric acid baths to stabilize the structure and remove encrustations—the remains are now stable enough to be displayed in the open air. While some components are in surprisingly good condition, much of the skin is heavily corroded. A wing is now on display in the Conservation Centre, alongside the aircraft’s engines and propeller, next to the museum’s sole surviving fully restored Boulton Paul Defiant—fittingly, the type that shot it down. The fuselage remains in storage at the Centre for now.

The LVG C.VI (serial 7198/18, civil reg. G-AANJ) was acquired by the RAF after the First World War and, though occasionally flown, spent much of its life in storage. On loan to the Shuttleworth Collection from 1959, it was restored to airworthy condition over an extended period and flew again in 1972, becoming a crowd favorite at Old Warden airshows until 2003. The loan agreement ended around then, reportedly due to the discovery of delamination and needed repairs to maintain airworthiness, though there may have been other factors. Since then, the LVG has not been displayed publicly, except on rare Conservation Centre open days. Its fabric covering has been removed and the structure inspected, but little further restoration has taken place. A full restoration does not appear imminent, and it has even been suggested that it might be displayed uncovered to reveal its underlying structure, perhaps with half the aircraft covered and half exposed to better illustrate its construction.

The Fieseler Fi 156 Storch (werknummer 475081) was captured at the end of World War II, flown to the UK, and even displayed at Hendon during the September 1945 Battle of Britain display by none other than Eric “Winkle” Brown. Despite its provenance, it is now up for disposal after being on display at Cosford since 1989. Let’s hope it finds a good home—ideally at a UK museum—given its iconic status as a recognizable WWII German aircraft.

Several other aircraft in the Conservation Centre are either in storage or awaiting disposal. These include two Spitfires: Mk.24 PK724, formerly on long-term display at Hendon and likely to return to public view; and PR.XIX PM651, which has been shown at Cosford on occasion and also used as a traveling exhibit—something the museum plans to continue.

One of Cosford’s real treasures was its world-class collection of flight test aircraft, showcased in the “Research and Development Collection.” Unfortunately, this collection has been significantly reduced following a controversial decision to remove roughly half of the aircraft. The justification offered was that these types weren’t in RAF service, although many contributed directly to the development of in-service aircraft. While the aircraft on the disposal list are currently only offered on loan—not for permanent transfer—there is hope that a new building might eventually be constructed to house them. Public outrage followed the decision to leave some of these aircraft exposed outdoors for six months; they are now at least stored under cover. The spectacular Bristol 188, a high-speed research aircraft developed as part of the Avro 730 Mach 3 bomber project, is now in a storage hangar. It’s hoped it may transfer to Aerospace Bristol. Much of the flight data from the 188 was later used in the development of Concorde.

Also in the Conservation Centre are two aircraft previously listed for disposal, but still awaiting new homes: the futuristic Saunders-Roe SR.53 XD145, powered by a Spectre rocket and Armstrong Siddeley Viper jet, which flew only briefly in 1957–58 before being displayed at Cosford since 1982; and the dumpy Hunting H.126 XN714, a blown-flap STOL research aircraft operated from 1963–67 and tested further in NASA wind tunnels in 1969. It arrived at Cosford in 1974 and remained on display until 2022.

New Developments

Good news comes in the form of a planned large storage hangar to be built adjacent to the MBCC, scheduled to open in 2027. It will be four times the size of the MBCC and will house all stored aircraft currently at RAF Stafford and other sites. Crucially, this new facility will be open to the public, though how access will be provided is not yet confirmed. A walk-around mezzanine would be ideal to allow overhead viewing. However, given the recent disposals, it’s fair to ask what will actually remain to be seen. A major upcoming initiative is the refurbishment of Hangar 1, which will reopen with a new exhibition focused on the RAF from the 1980s to the present. Most of the current exhibits in Hangar 1 will not feature in the new display and some have been added to the disposals list. Artist impressions show a sparsely populated hangar, raising concerns that these empty spaces might be filled with irrelevant display cabinets—or worse, life-sized cardboard or plastic cut-out figures, which have already spoiled views and photography at Hendon. Hendon previously converted the “Milestones of Flight” gallery into an exhibit of RAF aircraft from a similar era, which appears to be less popular than the main museum. Similarly, the excellent Grahame White Factory WWI display often appears under-visited. It will be interesting to see how successful this new exhibit proves to be.

Disposals and Contradictions

Museum management insists disposals are limited to duplicates or aircraft not directly representing RAF service, such as research aircraft or enemy types like the Junkers Ju 52/3m, recently deaccessioned due to being a Spanish-built CASA 352L. Yet, oddly, unrelated items such as 1950s cars, a German and Czech tank, and other non-RAF exhibits remain in the Cold War hangar—reportedly a concession to satisfy Heritage Lottery Fund requirements. Even more bizarre is the recent announcement that Hangar 1 will include a full-scale model of the proposed BAE Tempest fighter—an aircraft not yet in service—occupying valuable space that could have been used for a historic aircraft now being discarded.

I was told that the Armstrong Whitworth Argosy C.1 XP411 will be retained and displayed outdoors—though ideally, space might be found in the Cold War hangar. That’s a challenge given the hangar’s layout and the relevance of the aircraft already on display. Perhaps relocating the gift shop could help. The HS Andover E.3A XS639 is also expected to be displayed outside.

The Consolidated PBY-6A Catalina (L-866) in Danish Air Force markings remains outside, displaced to make room for simulator games several years ago. While no RAF Coastal Command Catalinas survive, this aircraft represents the more than 600 Catalinas that served the RAF during WWII. Exposure has damaged its fabric-covered areas, prompting removal of fabric from parts of the wing to prevent water accumulation. It must be moved indoors soon to prevent further deterioration. Also currently outside is Dutch Navy Lockheed Neptune 204, which is scheduled for disposal.

The Avro Anson C.19 TX214, in service from 1945, was based at RAF Hendon on its last operational day and on display at Cosford since 1978. It has recently been transferred to the Avro Heritage Museum at Woodford—a fitting home, especially compared to the Shuttleworth Collection’s airworthy example, which BAE originally considered donating instead.

While some disposals—especially of smaller aircraft—benefit other museums, and some have little RAF relevance (e.g., the Comper Swift, now at Hooton Park), the fate of others remains uncertain. The full list of aircraft up for disposal, bids for which closed at the end of April, so we now await to see their fate.

Vickers Varsity WL679, although it never served in the RAF, gave sterling service with the Royal Aircraft Establishment and other Ministry of Defence organisations for 37 years, from 1954 until its retirement in 1991. It stands as an excellent representative of the 160 Varsitys that served in the RAF training role for 25 years and is in remarkably good condition.

De Havilland Comet 1XB G-APAS/XM823, although used only for trials after initial commercial operation by Air France, is a historically significant aircraft. It is the only complete surviving Comet 1; the other five or six preserved Comets are all the larger, later Comet 4 variants.

Vickers Valetta C.2 VX573 is one of only two surviving Valettas—the other being outdoors at the Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum in Flixton. This airframe was transferred to the RAF Museum and briefly displayed outside during the 1980s but has since been stored out of public view in a hangar.

Lockheed Ventura II AJ469 was exchanged with the South African Air Force Museum for the Airspeed Oxford G-AITF, which has since been fully restored and is now on display in Port Elizabeth. Sadly, the Ventura has never been exhibited nor restored. It has simply been relocated from one storage hangar to another over the years.

FMA IA-58 Pucará A-515 was one of 24 Pucarás operated during the Argentine occupation of the Falkland Islands. It took part in the last Pucará mission of the war, sustaining small arms fire but landing safely. One of only three airworthy examples remaining at the time of the Argentine surrender, A-515 was brought to the UK and became the only one of its type flown here. It was assigned the RAF serial ZD485 and flew for around 25 hours from Boscombe Down, including appearances at several airshows during the summer of 1983. It was then flown to Cosford and placed on display. While Pucarás were not directly engaged by RAF aircraft during the conflict, they were still considered a significant threat in the air war. Nevertheless, the RAF Museum management does not regard the Pucará as sufficiently relevant to help tell the story of the Falklands conflict alongside the Chinook and Harrier.

De Havilland Canada Chipmunk T.10 WP962 served with the RAF from 1953 to 1998 and was one of two Chipmunks that took part in Exercise Northern Venture during the summer of 1997—a round-the-world circumnavigation flight. The aircraft flew all the way across Russia, becoming the first Western light aircraft to do so. The flight took 64 days, covering 16,259 miles and visiting 62 airfields, along with sister ship WP833. While WP833 was later sold and is now well cared for by Richard Wilsher in California, WP962 had been on display at the RAF Museum Hendon since 2000. Despite its historic journey, it is now deemed surplus to requirements. The museum does, however, still retain Chipmunk WP912, which the late Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, flew for his first solo.

Boulton Paul Sea Balliol T.21 WL732 is the only remaining original Balliol in the UK. While another accurate replica built from original parts exists, the only other surviving examples are two held by the Sri Lanka Air Force Museum—the only export customer. Initially designed as a turboprop trainer, the Balliol was, in fact, the first single-engine turboprop aircraft to fly in the world. Engine reliability issues meant that production aircraft were ultimately powered by Rolls-Royce Merlins. This particular example is a Sea Balliol delivered to the Royal Navy in 1954, but it never entered service, as the type was already being phased out in favor of jets. Lucky to avoid the scrap heap, it was transferred to Boscombe Down for spares, then restored to flying condition to replace another aircraft, becoming the last Balliol to fly. In addition to flight testing, it was used to train Battle of Britain Memorial Flight pilots transitioning to the Spitfire. Its final flight took place in 1969, after which it was transferred to the RAF Museum. It was displayed at Cosford intermittently from 1979 until a few years ago. There is hope that it will now be transferred to the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovilton.

Fairchild UC-61A Forwarder (RAF Argus II) G-AIZE was built as part of a batch for the United States Army Air Corps, many of which were provided to the RAF under Lend-Lease. This example, however, was retained by the USAAC and delivered to England in 1943, likely serving as a transport or liaison aircraft with the 8th Air Force. Civilianised in 1946 as G-AIZE, it remained active with private owners in the UK until 1966, when it was placed in storage. It was sold to the RAF Museum in 1973 and remained in storage for many years before being restored between 1997 and 1999 by the Medway Aircraft Preservation Society in Rochester. It now wears RAF South East Asia Command (SEAC) colors with serial FS628, representing one of the many Fairchild Argus aircraft that operated in that theatre. It has been on display at Cosford since restoration.

De Havilland Devon C.2 VP952 was delivered to the RAF in 1947 and remained in service until 1984, making it the oldest operational aircraft in the RAF at the time of its retirement, as well as the longest-serving. It was one of the last aircraft to leave RAF Hendon and participated in the station’s closure flypast. The aircraft has been on display at Cosford since 1986.

Fairey Swordfish IV HS503 began service with the Royal Navy but was later transferred to the Royal Canadian Air Force. It was part of the Ernie Simmonds collection—an assemblage that once included six Swordfish, 36 North American Yales, and many others. After Simmonds’s death in 1970, the collection was auctioned off. This aircraft briefly passed through the Canadian National Museum at Rockcliffe before being acquired by the RAF Museum in 1970 as a restoration project. It has remained in storage ever since. While RAF Coastal Command did operate Swordfish aircraft early in WWII—mining enemy harbors and later using them for radar-guided submarine hunting—most Swordfish were Navy-operated.

While it is certainly disappointing that the RAF Museum is disposing of so many historical aircraft, it is also true that some of these do not meet the museum’s increasingly strict criteria of RAF service. That said, several aircraft still in the collection also fall outside that scope, including enemy types and aircraft operated by allies, such as the USAF F-111. A fundamental issue is that the UK lacks a unified National Aviation Museum. Many of these aircraft would be better suited to such an institution—especially those with a focus on research, development, and trials. A national collection could also provide a proper home for long-stored Science Museum aircraft and the excellent but underappreciated Duxford Aviation Society’s airliner collection, which is sadly neglected under current IWM oversight. The silver lining is that many of these disposals will find new homes at small, enthusiast-led museums. This is a significant win for aviation fans, as it means long-stored aircraft may finally return to public view. And it’s important to remember: this round of disposals represents only a small fraction of the total RAF Museum collection. Many rare and fascinating aircraft remain on display at the RAF Museum Midlands (Cosford), which continues to be well worth a visit. A few highlights are included below!

So shortsighted, penny-pinching and pettifogging an approach to Britain’s aeronautical heritage, as if these aircraft were not ALL intimately related to the RAF through service, conflict, research and engineering progress. A fine memorial to the loss of world-leading expertise in response to politicians’ preoccupations.

Having been to Cosford and the Airshow I love their aircraft.

I find it shocking that they are offloading significant aircraft based on a made up rule. Aircraft left outside have now been given a death sentence.

Cosford have many hangars available on the RAF side which I am sure could be used. This year’s air show had a huge hanger for STEM with basically nothing in it.

Whoever thinks this reorganization is a good idea needs to have a rethink.

Finally I have been waiting to see the Hampden for years and it’s going straight to Hendon? Come on it on display at Cosford where all the hard work was done

Cosford’s management would be well advised to visit the USAF museum at Dayton, Ohio. A large number of experimental types in a dedicated gallery. The Americans know what they’re doing!

I agree with you. I loved to see the surviving XB 70 Valkyrie bomber.

And all the other exhibits as well.

The museum doesn’t have access to the other hangars at Cosford because they are on an active RAF station, and the museum it’s not owned or run by the RAF. It is an individual charity

There is a piece about the Dornier wing being on display in the conservation centre next to the Boulton Paul Defiant. This is incorrect, as it’s actually on display in the War On The Air Hangar, next to the Boulton Paul Defiant, having been moved from the Conservation Centre.

For too many years museums in Britain, as elsewhere, have had to deal with the twin evils, lack of Display/Storage Space and lack of funds.

Especially, those looking to preserve relatively modern items, and especially those items of a military nature.

A third, and greater evil, has arisen over the last ten to fifteen years; those Museum Directors who prefer … ‘Dumbing Down’, and ‘Artful Displays’ … of just One or Two items, surrounded by a great deal of, very precious, wasted space.

I took a German friend to view the new WW1 Gallery at the IWM a few years back; having toured the whole Site, we couldn’t believe the sheer waste of Display Space, and the general lack of exhibit information.

The same story was repeated at the National Maritime Museum and others;

all previously awash with exhibits.

Sadly, it appears too many Modern

Directors are only concerned with Income Revenue, and not education; the exhibits are now almost an irrelevance.

And what is a Museum for, if not education?

”If you don’t know your history …”

Is this an old article? The Spanish-built CASA 352 has been at the Kent Battle of Britain Museum for a couple of years.

As it says in the article, it was from a visit in March 2025, published in June 2025.

Yes the CASA 352 has gone, that’s why I used it as an example of aircraft that had already been disposed of.