In the more popular accounts of British WWII heavy bombers, the Handley Page Halifax is often overshadowed by the legacy of its wartime comrade, the Avro Lancaster. But at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alberta, an ambitious project is currently underway to rebuild a complete example of this aircraft, with the goal of honoring the sacrifices of the members of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) killed in action flying the Halifax in their effort to help defeat Nazi Germany. The Handley Page Halifax was originally developed as the HP.57, a four-engine development of two twin-engine designs that never made it off the drawing board (the HP.55 and the HP.56). The first prototype, serial number L7244, made its first flight on October 25, 1939, with the second prototype flying on August 17, 1940, one month before the type was officially named for Lord Halifax, then the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. The Halifax bomber then entered operational service with No. 35 Squadron RAF in November 1940 and flew its first combat mission on the night of 10–11 March 1941, when six Halifaxes attacked the German-occupied French port of Le Havre. The first main variant of the Halifax, the B.I, was powered by the Rolls Royce Merlin engine. Unfortunately, the early Halifaxes had a few significant issues. For one, several losses of fully loaded Halifax bombers from going into uncontrollable spins was attributed to the triangular shape of the two vertical stabilizers on the tail, which resulted in the introduction of larger, rectangular fins by early 1943.

Another challenge proved more difficult to overcome. Although the Halifax and Lancaster were both powered by the Rolls Royce Merlin, it was found that the propellers on the Halifax were placed too close to the leading edges of the wings, disrupting the airflow, and restricting the aircraft’s speed and service ceiling to the point where it could keep up with the Lancaster in terms of speed and altitude, leading to higher loss rates to German fighters. They could not fly as the Lancaster, which led to high loss rates to German fighters. The Halifax also carried a smaller bombload than the Avro Lancaster, which led to Air Chief Marshal Arthur “Bomber” Harris, head of RAF Bomber Command, preferring the Lancaster over the Halifax.

But this would not define the Halifax’s wartime record. Engineers at Handley Page raced to add improvements to the design, and aircrews assigned to fly the Halifax came to respect the aircraft for its ability to sustain heavy damage and make it home. In the event the crew was forced to bail out of a stricken Halifax, though, the aircraft’s escape hatches were larger and more accessible than those on the Lancaster. What’s more, a redesign of the aircraft resulted in the H.P.59/B.II variant, which was fitted with upgraded Merlin engines, while the H.P.61/B/B.III variant, introduced in late 1943, was fitted with four Bristol Hercules radial engines, which produced more horsepower than the Merlins, and allowed the Halifax’s performance to be on par with the Lancaster while also forgoing the B.I’s nose turret for a plexiglass nose for the bomb aimer with a single machine gun. Following the introduction of these new variants, loss rates among Halifax crews dropped in RAF casualty reports. Even as early as the summer of 1942, though, “Bomber” Harris’s view of the Handley Page Halifax had already begun to change. In replying to a congratulatory telegram sent by Frederick Handley Page regarding the success of the first 1000 bomber Cologne raid, Harris said: “My Dear Handley Page. We much appreciate your telegram of congratulations on Saturday night’s work, the success of which was very largely due to your support in giving us such a powerful weapon to wield. Between us, we will make a job of it.”

Nevertheless, while production continued on the production of the Halifax, the British Air Ministry placed greater production emphasis on the Avro Lancaster, which was reserved primarily for RAF Bomber Command. However, this shift in industrial output allowed the Halifax to be introduced into new roles and replaced older types, becoming more obsolete as the war went on. Over the course of the war, many Halifax’s were operated by nine squadrons of RAF Coastal Command in conducting anti-submarine warfare, weather reconnaissance for meteorological reports, maritime reconnaissance, and laying mines near German-held ports. RAF Transport Command flew Merlina and Hercules-powered Halifaxes to tow combat gliders, haul cargo, evacuate casualties, and carry high-ranking personnel. Some aircraft were also used in electronic warfare to jam German radar units or even covertly drop special agents and equipment into German-occupied Europe on behalf of the Special Operations Executive (SOE).

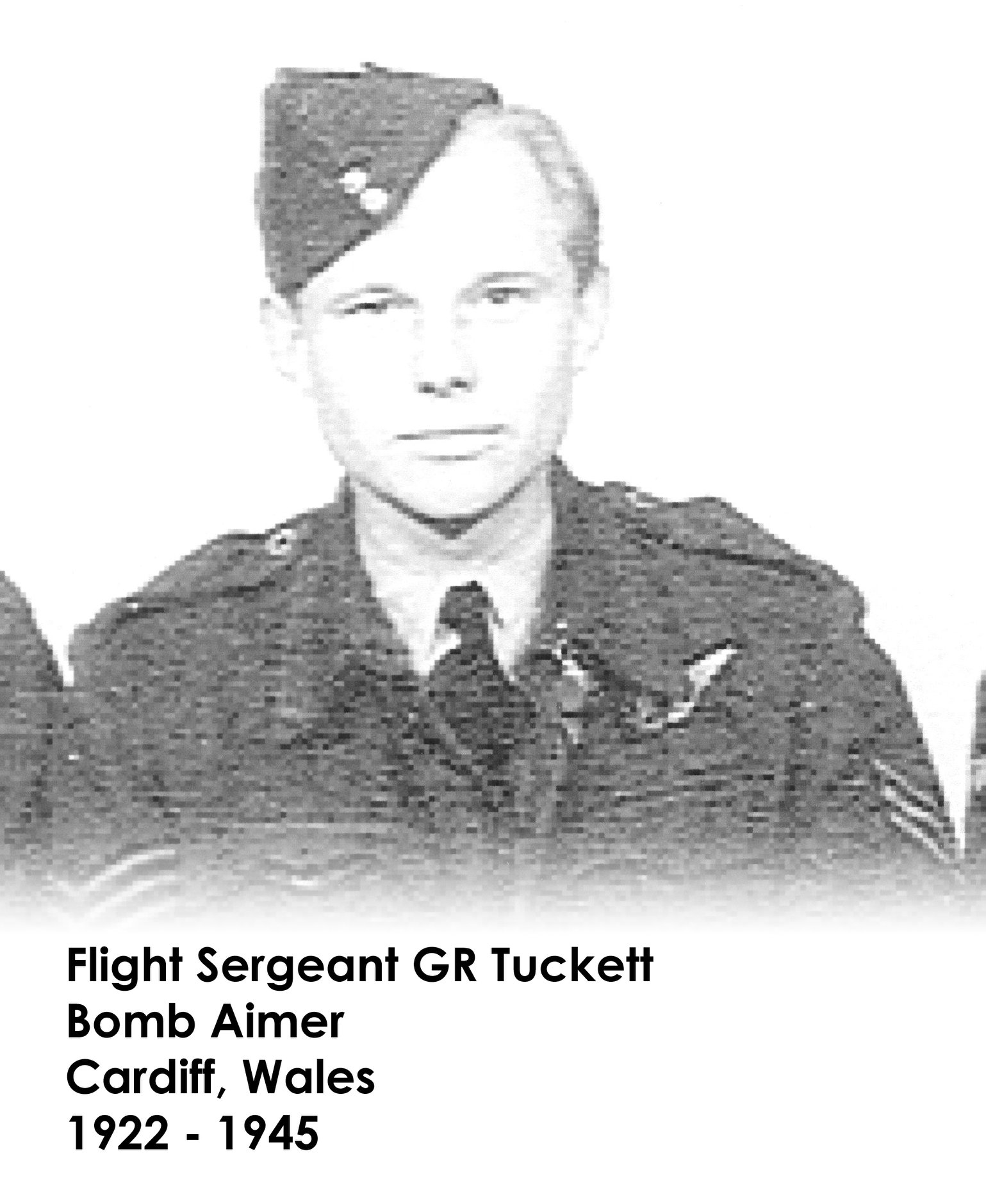

Yet still, the Handley Page Halifax’s greatest contribution was in its intended role as a bomber. By the end of the aircraft’s production run in April 1945, 6,178 aircraft had been constructed. Of these, 4,751 were built as bombers, which completed around 75,000 sorties, dropping close to a quarter of a million tons of bombs between 1941 and 1945. The aircraft was also flown by many of the Allied and Commonwealth air forces. In addition to being flown by Free French and exiled Polish crews, the Halifax was flown by every heavy bomber squadron of the Royal Canadian Air Force for at least some portion of the war. Of the more than 75,000 bombing missions flown by the Halifax, around 29,000 were flown by RCAF pilots, co-pilots/flight engineers, navigators, bomb aimers, radio operators, and gunners, with about 28,000 of the 40,000 bomber combat flights flown by RCAF squadrons in the British RAF Bomber Command being flown on Halifaxes.

As far as Canadian airmen killed in action during the Second World War as concerned, though, more Canadian bomber crews were killed flying Handley Page Halifaxes than any other bomber aircraft of WWII, with over 60% of the 10,659 RCAF Canadian airmen killed in action in bombers being lost in Halifaxes, along with over 60% of the 1,592 British airmen of the RAF killed in action while flying with Canadian bomber squadrons and over 60% of the 840 American volunteers in the RCAF who were killed in action being shot down in Halifax bombers.

With the war’s end in 1945, most Halifaxes were scrapped during the late 1940s, though a number remained in service with the RAF Coastal Command, RAF Transport Command, Royal Egyptian Air Force and the French Armée de l’Air until early 1952. Some examples were also sold to civilian cargo companies and airlines for use as freighters, with a number becoming the Handley Page Halton. 41 civilianized Halifaxes were also used to land provisions in into West Berlin during the Berlin Airlift, with the final Halifax aircraft flown in military service being those of the Pakistani Air Force.

Today, the only Handley Page Halifax bombers on public display have had to be resurrected from submerged wrecks or pieces of scrap metal. In June 1973, the Royal Air Force Museum in Hendon, London funded the successful recovery of Halifax B.Mk.II s/n W1048 from the bottom of Lake Hoklingen, Norway, after it had been shot down by German anti-aircraft batteries on April 28, 1942, during a mission to bomb the German battleship Tirpitz. While some components of the aircraft were restored, the remainder of W1048 is displayed unrestored as a tribute to the crews of Bomber Command.

Meanwhile, the Yorkshire Air Museum rebuilt a second Halifax, which incorporates the rear fuselage of Mk.II s/n HR792, parts of Halifaxes LW687 & JP158 and the wings and undercarriage of a Handley Page Hastings transport, serial number TG536. Today, this aircraft, rebuilt as a Hercules-powered Mk.III, proudly wears the colors of two wartime Halifax bombers, s/n LV907 “Friday the 13th” of No. 158 Squadron RAF and NP763, a Free French Air Force Halifax of No. 346 Squadron RAF (GB II/23 Guyenne).

In returning to the Halifax’s Canadian connection, one man has led the charge in preserving the aircraft’s legacy with the RCAF, and that man is Karl Kjarsgaard. Having flown as a commercial pilot for Canadian Airlines and Air Canada, Kjarsgaard had also received flying lessons from Alexander James Alan Laing, a former Spitfire pilot who had flown in the Battle of Britain as part of No. 64 Squadron RAF, and from Ken Brown, one of the Lancaster pilots that participated in Operation Chastise, the famed Dambusters Raid of 1943.

In 1995, Karl helped organize the recovery of Halifax NA337, a Mk.VIIa/A.VII paratrooper transport/glider tug of No. 644 Squadron RAF. On the night of April 23-24, 1945, NA337 performed a supply drop mission for the Norwegian resistance and was on its way back to England when it was hit by German anti-aircraft guns while flying over a railway bridge in Minnesund. With its fuel tanks in the right wing ruptured and on fire, NA337’s pilot, Flight Lieutenant Alexander Turnbull, made a rough ditching on Lake Mjøsa at around 2:00am. Though the six-man crew survived the landing, five of the crew died from hypothermia in the freezing lake. Only the tail gunner, Flight Sergeant Thomas Weightman survived by clinging to a dinghy after initially being knocked unconscious in the hard water landing. Though rescued by Norwegian resistance members, Weightman was later handed over to the Germans to avoid harsh reprisals. Just 14 days later, though, Victory in Europe was declared, and Weightman was soon flown back to England.

Years after the war, locals Tore Marsoe and Rolf Liberg, who had lived through the war as teenagers, were determined to find the Halifax that had gone down in Lake Mjøsa, as Marsoe had remembered hearing the aircraft pass overhead before the ditching. Upon searching the lake on a boat with a fish finder, the sonar picked up the unmistakable profile of a Handley Page Halifax 750 feet below the surface of Norway’s largest lake. With the help of Norwegian, British, and Canadian salvage experts, the aircraft was raised from the lake, and the recovery was celebrated by aviation enthusiasts around the world.

When the aircraft was recovered, the sole survivor of that forced landing, Thomas Weightman, was invited to see the aircraft for the first time in 50 years. So well preserved was Halifax NA337 that Weightman’s coffee thermos was still sitting near the tail turret! Once carefully disassembled, Halifax NA337 was transported across the Atlantic to the National Air Force Museum of Canada at Canadian Forces Base Trenton. Over the next nine years, the aircraft underwent a painstaking restoration and was officially dedicated at the museum in November 2005, with many WWII RCAF veterans and their families in attendance, and Halifax NA337 remains proudly on display in Trenton to this day.

Having recovered and restored Halifax NA337, Karl Kjarsgaard has dedicated the last 20 years to recovering additional Halifax wrecks for restoration in Canada. To accomplish this, Karl, who has become the Museum Director of the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, has also become the director of Halifax 57 Rescue (Canada), a project dedicated to the recovery and restoration of more Halifax bombers, with the immediate goal of having one on display at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, which also has an Avro Lancaster, serial number FM159, maintained in ground running condition.

Presently, there are at least two airframes that Kjarsgaard has set his sights on raising from the depths. One is Halifax Mk. I s/n HR871. This aircraft was flown by No. 405 Squadron RCAF (now 405 Long Range Patrol Squadron). The squadron served as Pathfinders, flying ahead of the main body of bomber formations in order to identify targets and mark the routes to get to and from the target area for the main bomber force to ensure greater accuracy while bombing at night. On the night of August 2-3, 1943, RAF Bomber Command sent a massive force of bombers against the German city of Hamburg as part of the final night mission of Operation Gomorrah. Despite having to fly near a thunderstorm, the crew got dropped the target indicators (TIs) over their objective. But then, a bolt of lightning struck the forward section of the Halifax, disabling the two inboard engines (no. 2 and no. 3 engines), several key instruments, and the radio. The pilot, Sergeant John Alywyn Phillips, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserves, was even temporarily blinded by the flash, losing control before regaining his sight. Considering the condition of the aircraft and the safety of the crew, Phillips decided against flying in inclement weather across the North Sea without a working radio and instead turned towards neutral Sweden.

Upon visually identifying the lighthouse at Falsterbo on the southwestern coast of Sweden, Phillips flew the crippled bomber deep into Swedish airspace, giving his crew the best chance to bail out over land. One by one, the crew bailed out over Sweden, and once he knew he was the last man aboard HR871, Phillips put the aircraft on a southwesterly course back towards the Baltic and set the trim tabs to keep the Halifax steady until it would hit the water, far beyond any chance of hitting anyone. Then he too threw himself into the night. Fortunately, all seven of HR871’s crew survived the jump and were interned in Sweden until they were flown back to England in January 1944.

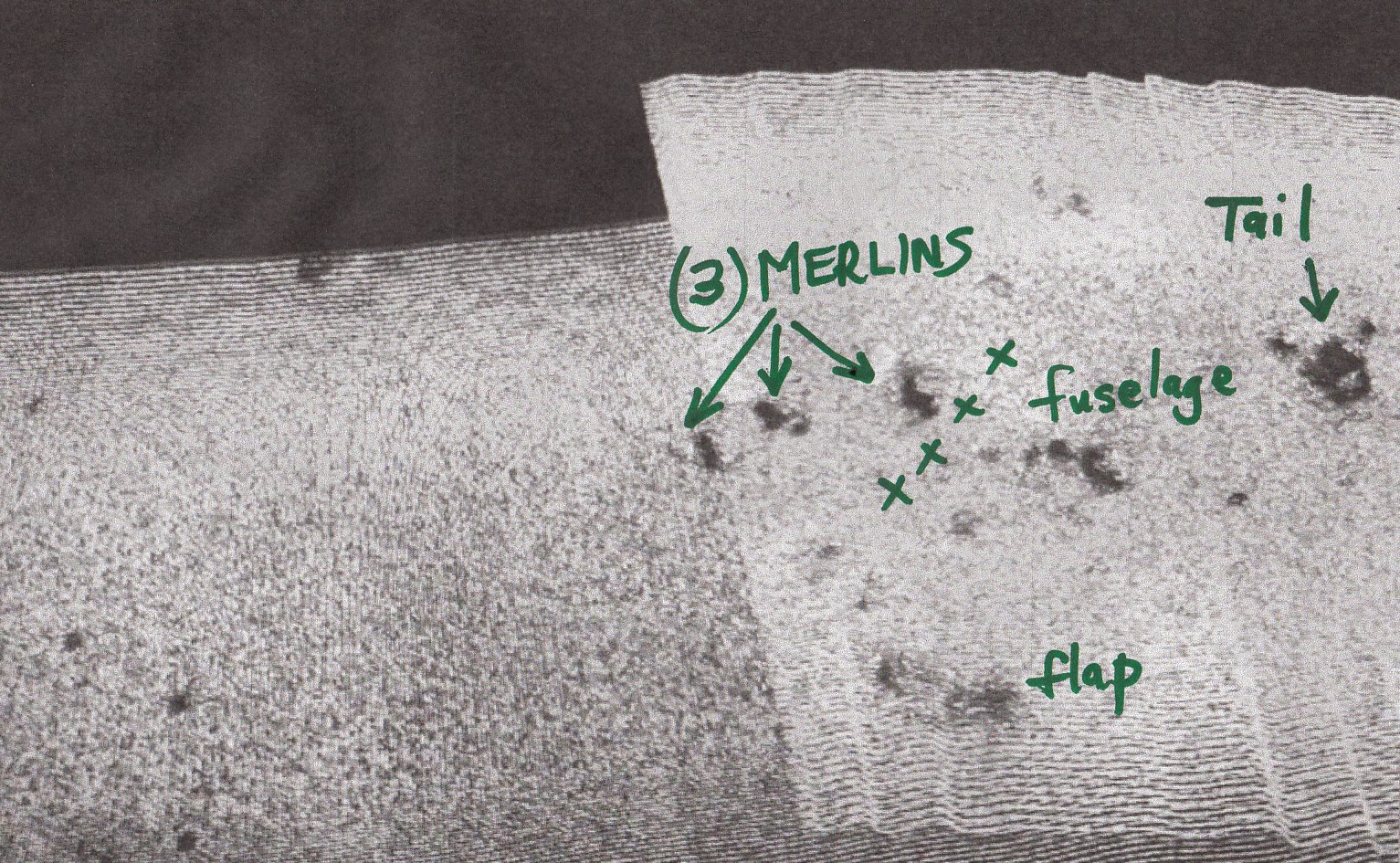

As for HR871, its wreckage was discovered lying 17 meters (50 feet) off the Swedish coast. Though components of the aircraft came apart after its impact with the surface of the Baltic Sea, with three of the Merlin engines, tail, fuselage and flaps lying separately, the low levels of salinity in the waters of this local area and the fact that much of the wreckage has been buried in sand meant that corrosion was less severe than if the aircraft was found at deeper depths. In the 15 or so years since the rediscovery of HR871, parts of the aircraft have been retrieved from the sea floor, with Halifax 57 Rescue (Canada) working in conjunction with British and Swedish groups to accomplish this. Additionally, remnants of the aircraft have been brought to the RAF Snaith Museum in Pollington, England.

While the team was also interested in recovering the remains of Halifax Mk.III s/n LW170, a veteran of over 20 combat missions (including an overnight mission on June 5 and 6, 1944 in the predawn hours of D-Day) with No. 424 Squadron RCAF, the aircraft was lost on August 10, 1945, while conducting a “Bismuth” (British Isles Met Unit Temperature and Humidity) weather reconnaissance mission over the Atlantic Ocean and the Irish Sea with No. 518 Squadron RAF, a meteorological reconnaissance squadron stationed at RAF Tiree, Hebrides, Scotland. LW170’s crew was rescued, and the wreckage was later discovered and proposed for recovery by Halifax 57 Rescue, but unfortunately, recent developments have made Karl scrap this recovery effort, but there is the possibility that other underwater Halifax wrecks could be looked at for potential recovery.

Across the Atlantic, the focus of the restoration rests on assembling as many parts as possible to represent a Halifax at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada. Much of the restoration work on the wings and fuselage of the aircraft at a hangar at Arnprior Airport (CNP3) in Arnprior, Ontario, around 50 kilometers (31 miles) west of Ottawa, while Karl is also overseeing the project’s Bristol Hercules engines, propellers, turrets, and other systems at the museum in Nanton, over 1,700 miles (2,800 kilometers) away from Arnprior.

At the end of 2023, Vintage Aviation News published a short article about the RAF Museum donating the right outer wing of Handley Page Hastings transport TG568 to the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, while the left outer wing panel from TG536, the Hastings transport used to rebuild the Yorkshire Air Museum’s Halifax, was also selected for shipment to Canada. In July 2024, the two wing panels were loaded aboard an RCAF C-17 Globemaster III of 429 Transport Squadron at Prestwick, Scotland and flown to CFB Trenton, Ontario. Fittingly, 429 Transport Squadron had previously been No. 429 (Bomber) Squadron RCAF, which had flown Halifaxes in the European Theater of Operations from August 1943 to March 1945.

Perhaps the biggest development for the project this year to date is the upcoming arrival to Arnprior of a 20–foot container filled with two Bristol Hercules engines and their cowlings, landing gear, tires, gas tanks, engine parts, and 7 new propeller blades. These items were collected by the Halifax 57 Rescue team over the past 3 to 5 years across the UK and the Netherlands, and on August 2, the container began its journey across the Atlantic by ship. Karl expects to have the container arrive in Arnprior between August 12 and 14, and will oversee the unpacking process, just as he oversaw the packing of the container in the UK.

Meanwhile, construction of the wings has been one of the most extensive aspects of the project. With all the Halifaxes that survived WWII having been scrapped, one of the biggest challenges was to find a set of wing spars to hold the bomber’s massive wings up. Like the reconstruction of the Yorkshire Air Museum’s Halifax, finding the remains of Handley Page Hastings transports has proven vital to the current success of the Halifax 57 Rescue project. In addition to the wings of the Halifax being used as a basis for the wings of the Hastings troop carrier/freight transport, the aircraft was also powered by four Bristol Hercules engines.

One place where the project has found success in finding Hastings parts has been Malta. In 1968, two Handley Page Hastings of the RAF, serial number WJ325 and WJ328 were struck off charge at RAF Luqa (now Malta International Airport) and used for airport firefighter training. In 2010, the cockpits and wing center sections of WJ325 and WJ328 were brought to the attention of the Malta Aviation Museum in Ta Qali when they were recognized to be in a local scrapyard. In 2011, the two nose sections were donated to the Malta Aviation Museum, while Karl Kjarsgaard and other members of the Halifax 57 Rescue (Canada) group worked to acquire the wing center section and engines of Hastings WJ328 on behalf of the Bomber Command Museum of Canada.

While the wings and undercarriage of the Hastings from Malta have been the subject of intensive restoration work at the Arnprior rebuild shop, the team at the Bomber Command Museum of Canada has restored several of the Bristol Hercules engines to running condition. One of the ways that the project attracts public attention and donations is through conducting demonstration runs of the Hercules engine (one of the more recent can be found HERE: Halifax 57 Rescue Show 24 2025 – YouTube). Additionally, Karl has been interviewed on numerous programs over the years, with the Commemorative Air Force’s YouTube channel CAF Media having produced several update videos on the project such as this one (CAF Warbird Tube: Halifax Bomber Restoration Update – YouTube), and for a complete listing of videos about the Karl’s efforts to restore Handley Pages Halifaxes around the world, recorded interviews with Halifax veterans, and more, check out the YouTube channel The TimeKeepers Canada Story. For more information, you can also visit www.halifax57rescue.ca.

Some may ask, why go to such great lengths to rebuild an airplane that few have ever heard of? The reason is simple: it is because of the sacrifices made by the thousands of airmen and maintainers who kept the Handley Page Halifax flying, to honor the men and women who built them in England, and to honor those who gave the ultimate sacrifice that thousands of young men made. As mentioned earlier, over 60% of the 10,659 RCAF Canadian airmen killed in action flying bombers in WWII were in Halifaxes, as opposed to 20% in Lancasters and 20% in Wellingtons, over 60% of the 1,592 British airmen of the RAF killed in action while flying with Canadian bomber squadrons were in Halifaxes, and over 60% of the 840 American volunteers in the RCAF who were killed in action being shot down in Halifax bombers. The BCMC in Nanton has memorialized these men in granite, and in their virtual memorial, you can access here: Bomber Command Museum of Canada Archives – Aircrew Losses.

For American enthusiasts, rebuilding a Handley Page Halifax today can be seen in the same light in which a dedicated American may attempt to rebuild a Consolidated B-24 Liberator, for just as the Liberator and its crews have been overshadowed in the public eye by the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, the legacy of the Handley Page Halifax has often been overshadowed by that of the Avro Lancaster, and just as the B-17s were kept in service in new roles after WWII to be preserved in greater numbers than the B-24 Liberator, so too was the Avro Lancaster kept in service long enough for surviving airframes to be preserved long after the Handley Page Halifaxes had been scrapped. This is not to say that the crews of the B-17s or Lancasters deserve less praise, but that the effort to rebuild a Halifax in Canada to honor the Canadian, British, and American airmen who flew on them is indeed fitting, especially for one to be displayed in the Bomber Command Museum of Canada. To learn more about the Halifax 57 Rescue (Canada) project and to keep up with the latest project updates, visit Halifax 57 Rescue (Canada) – FundRazr.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.

The Halifax was actually named as part of the policy of naming bombers after British cities. Hence the Manchester, Lancaster, Sterling, Sunderland, Lincoln etc. it was coincidence that Lord Halifax was foreign secretary at the time but was used to tie his colours to the mast by getting him to attend the inaugural event. Lord Halifax was a noted appeaser & peace at any price man at this stage.

Thank you for a story that will inspire and give a deeper love for the men and women that gave so much.