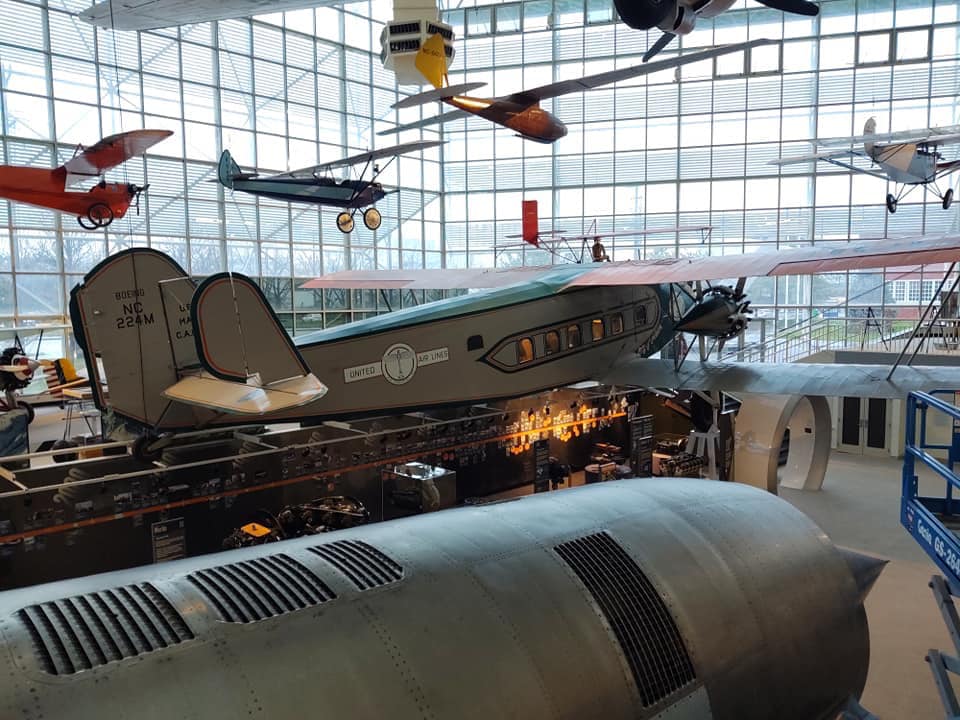

Since his childhood, Randy Malmstrom has had a passion for aviation history and historic military aircraft in particular. He has a particular penchant for documenting specific airframes with a highly detailed series of walk-around images and an in-depth exploration of their history, which have proved to be popular with many of those who have seen them, and we thought our readers would be equally fascinated too. This installment takes a look at the Museum of Flight‘s Boeing Model 80A-1 airliner.

This particular aircraft was built by Boeing Aircraft Company in 1929. It served with the United Aircraft Transport Company (William Boeing became the chairman of the company in 1929, the largest aircraft corporation at the time) until its retirement in 1934. In 1941, it was acquired by a construction firm for use in Alaska. To accommodate large equipment (including a 11,000 lb. (4,950 kg) boiler), a hole was cut into the side of the fuselage. Following World War II, this aircraft was put into storage and then placed in a dump.

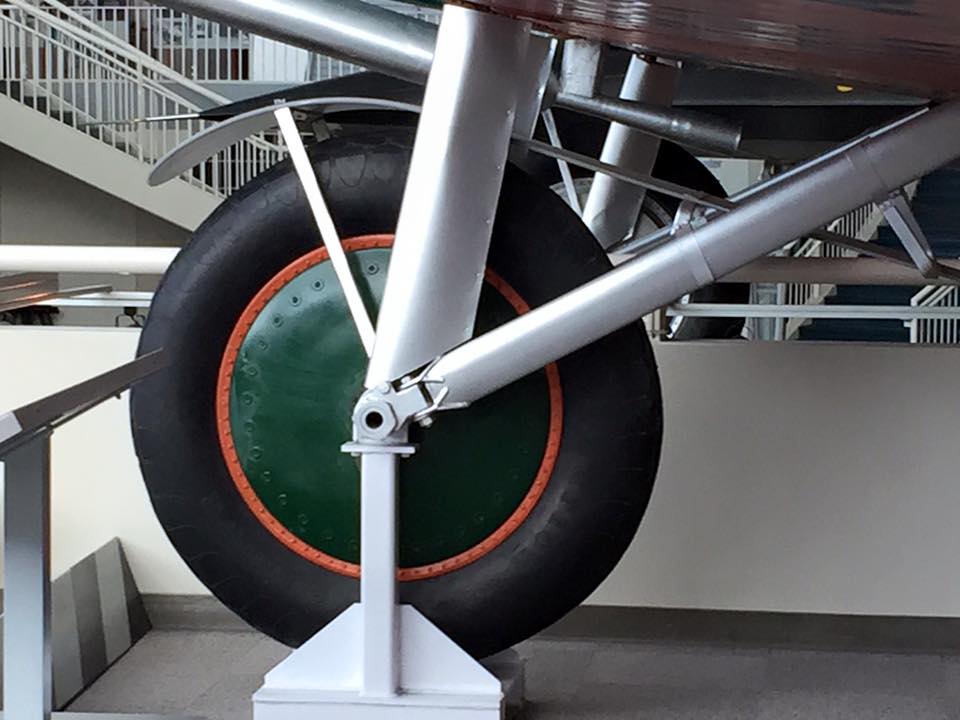

In 1960, it was recovered and restored and is now on static display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. My photos. The decade of the 1920’s saw the advent of civilian air transport and some of the earliest were the Ford Tri-Motor, the Fokker Tri-Motor, and the Boeing Model 80 Tri-Motor. The Model 80 12-passenger aircraft first flew in August 1928 and within two months was flying Boeing Air Transport flights within two weeks.

On February 9, 1934, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6591, stating that the Postmaster General of the United States declared all domestic air mail contracts for carrying the mails had been annulled, and ordering the Postmaster General, Secretary of War, and Secretary of Commerce “…cooperate to the end that necessary air mail service be afforded” and that “…the Secretary of War place at the disposal of the Postmaster General such airplanes, landing fields, pilots, and other employees and equipment of the Army of the United States needed or required for the transportation of mail, during the present emergency, by air over routes and schedules prescribed by the Postmaster General.”

In all, 262 Air Corps pilots were selected, none from the Corps training schools, and most had scant few hours logged in flying time (up to 4 hours per day) and even less in darkness or poor weather, and flying obsolete aircraft. 60 Air Corps pilots took the oath as postal employees. Poor weather and poor training resulted in 66 crashes involving 12 crew deaths, and the program was quickly discontinued in June 1934. The World War I ace Eddie Rickenbacker called the program “legalized murder,” and Charles Lindbergh said that using the Air Corps to carry mail was “unwarranted and contrary to American principles.” This attempt to use little-trained U.S. Army Air Corps pilots to deliver airmail resulted in the “Air Mail Scandal of 1934” (or “Air Mail Fiasco of 1934”), which involved a Congressional investigation and became a huge public relations disaster for the Air Corps. The Black-McKellar Bill became known as the Air Mail Act of June 12, 1934 (and later modified August 14, 1935), and the U.S. Department of Commerce renamed its Aeronautics Branch the “Bureau of Air Commerce” to be more aligned with the growing aircraft industry.

The consequences of which included (a) the growth of commercial air service including the establishment of the first air traffic control centers; and (b) the modernization of the Air Corps beginning with increased federal budget appropriations, increased training requirements, improved instrument training including the purchase of the first six Link Trainers (flight simulators), much improved radio communications that grew into a nationwide system with navigation aids. The Bureau also recommended an increase of 4,000 upgraded aircraft (and equipment) to be supplied to the Air Corp and U.S. Navy. General Benjamin “Benny” Foulois (who flew the first purpose-built military planes built by the Wright Brothers and was instrumental in U.S. Air Force development) wrote in his memoirs that “….the transport of the mail turned out to be a blessing for the Army and the country…Otherwise, I am convinced that we would never have recovered so quickly after the Pearl Harbor disaster.”

About the author

Randy Malmstrom grew up in a family steeped in aviation culture. His father, Bob, was still a cadet in training with the USAAF at the end of WWII, but did serve in Germany during the U.S. occupation in the immediate post-war period, where he had the opportunity to fly in a wide variety of types which flew in WWII. After returning to the States, Bob became a multi-engine aircraft sales manager and as such flew a wide variety of aircraft; Randy frequently accompanied him on these flights. Furthermore, Randy’s cousin, Einar Axel Malmstrom flew P-47 Thunderbolts with the 356th FG from RAF Martlesham Heath. He was commanding this unit at the time he was shot down over France on April 24th, 1944, spending the rest of the war as a prisoner of war. Following his repatriation at war’s end, Einar continued his military service, attaining the rank of Colonel. He was serving as Deputy Wing Commander of the 407th Strategic Fighter Wing at Great Falls AFB, MT at the time of his death in a T-33 training accident on August 21, 1954. The base was renamed in his honor in October 1955 and continues to serve in the present USAF as home to the 341st Missile Wing. Randy’s innate interest in history in general, and aviation history in particular, plus his educational background and passion for WWII warbirds, led him down his current path of capturing detailed aircraft walk-around photos and in-depth airframe histories, recording a precise description of a particular aircraft in all aspects.

Randy Malmstrom grew up in a family steeped in aviation culture. His father, Bob, was still a cadet in training with the USAAF at the end of WWII, but did serve in Germany during the U.S. occupation in the immediate post-war period, where he had the opportunity to fly in a wide variety of types which flew in WWII. After returning to the States, Bob became a multi-engine aircraft sales manager and as such flew a wide variety of aircraft; Randy frequently accompanied him on these flights. Furthermore, Randy’s cousin, Einar Axel Malmstrom flew P-47 Thunderbolts with the 356th FG from RAF Martlesham Heath. He was commanding this unit at the time he was shot down over France on April 24th, 1944, spending the rest of the war as a prisoner of war. Following his repatriation at war’s end, Einar continued his military service, attaining the rank of Colonel. He was serving as Deputy Wing Commander of the 407th Strategic Fighter Wing at Great Falls AFB, MT at the time of his death in a T-33 training accident on August 21, 1954. The base was renamed in his honor in October 1955 and continues to serve in the present USAF as home to the 341st Missile Wing. Randy’s innate interest in history in general, and aviation history in particular, plus his educational background and passion for WWII warbirds, led him down his current path of capturing detailed aircraft walk-around photos and in-depth airframe histories, recording a precise description of a particular aircraft in all aspects.