Located in the rolling forest-covered hills of northwest Arkansas, the city of Fayetteville is known to many as being the home of the University of Arkansas, but for aviation enthusiasts, Drake Field (also known as Fayetteville Executive Airport) is home to the Arkansas Air and Military Museum. Here, the history of the Diamond State’s legacy in aviation is well preserved, and the museum also honors both veterans of past wars and those in active duty today.

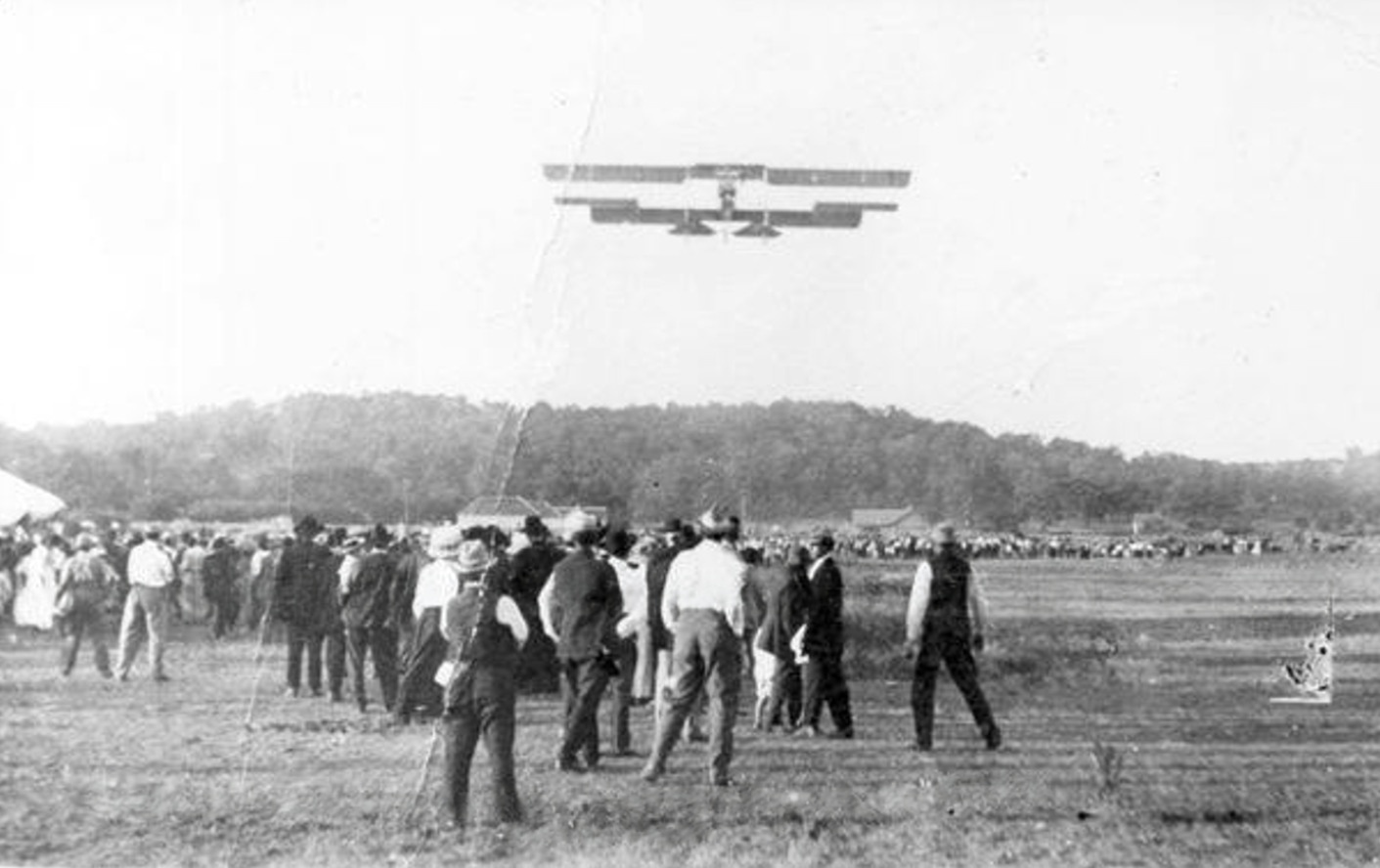

Fayetteville’s first experience with airplanes was on October 5, 1911, one year after the first recorded airplane flight in the state, which had been made in Fort Smith by James C. “Bud” Mars in a Curtiss Pusher on May 21, 1910. With the Washington County Fair to be held in the autumn of 1911, local store owner Jay Fulbright invited 25-year-old aviator Glenn L. Martin, who would go on to found the Glenn L. Martin Company that now constitutes part of Lockheed-Martin, to bring his airplane to the county fair. Martin accepted this offer, and after shipping the airplane to Fayetteville and reassembling it onsite, Martin took off on a short flight from the grounds of the Washington County Fair in Fayetteville in a pusher biplane built by Martin but sharing design elements from the contemporary Curtiss Pushers of the era, amazing the spectators gathered below seeing something that only a few years before would have been considered science fiction.

After WWI, Fayetteville provided the setting for the brief appearance of a rather unusual and ungainly flying machine, the Zerbe Air Sedan. Designed by Jerome (or James) Slough Zerbe (1849-1921), an engineer, patent attorney, and author on books for boys on mechanics, electricity, and aviation, whose first attempt at a multi-winged aircraft failed to fly at the 1910 Los Angeles International Air Meet at Dominguez Field, Zerbe had moved to Fayetteville in 1918. There he drew up plans for the Air Sedan, which was to be a quadruplane (with four pairs of wings) in a stepped configuration, a surplus French rotary engine (likely a Le Rhône), and a plywood passenger cabin. The roll axis of the aircraft was to be controlled not by ailerons but by wing-warping, a common practice with pre-WWI aircraft that had been phased out in favor of the more responsive authority offered by ailerons.

However, Zerbe died in New York before the construction of his creation was finished. Fortunately for him, former US Army Air Service pilot Thomas E. Flaherty completed the construction of the aircraft and in April 1921, during one of the high-speed taxiing tests at the fairgrounds, the Air Sedan reportedly took off, before one of the front wing supports broke, causing a wing to flop backwards and sending the Zerbe Air Sedan onto its nose, breaking its propeller and wheels. While some reports were certainly embellished, such as saying the aircraft flew up to 100 feet in the air and covered a distance of 1000 feet, an article published in the Arkansas Gazette on April 24, 1921, claimed the craft flew only six or seven feet off the ground before disaster struck. Though Flaherty survived the accident and told local newspapers that the aircraft would be repaired at once, the Zerbe Air Sedan quickly disappeared from the pages of history, never to be seen again.

In 1929, Fayetteville’s first dedicated airfield was created one mile north of the current site of today’s airport. In order to help establish this airfield, Dr. Noah Drake, a Professor of Geology at the University of Arkansas, donated $3,500 to purchase land for the construction of the airfield. But as bigger airplanes proved that this airfield was too small for regular air operations, the city approved of a bond worth $20,000 to establish Fayetteville Municipal Airport in 1936. It was still a humble grass airstrip with two wooden hangars, but in 1938, with war looming in Europe, the U.S. government sponsored the creation of the privately-operated Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP), a flight training program that worked to train civilian pilots for the growing aviation industry, but it was an open secret that the program was also created with the idea that qualified civilian pilots could then be trained as military pilots in the event of war.

The CPTP also worked with local colleges and universities across the country to offer students college credits for participation in flight training courses with the CPTP. In 1939, Fayetteville Airport would host its first CPTP class. Two years into training pilots through the Civilian Pilot Training Program, one of the two hangars at Fayetteville burned down in 1941, leaving many of the airplanes exposed to the weather. Later that year, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and America found itself at war, Fayetteville Municipal Airport was requisitioned for military flight training. In January 1942, the first class of the Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) War Training Service began training at Fayetteville and was later replaced by the 305th College Training Detachment.

Around this time, Henry George, the local fire chief for Fayetteville and a self-taught engineer, came up with an idea for a domed hangar large enough to house up to 40 training aircraft on the field, with many of these being Piper J-3 Cubs, some of which would be tipped on their noses to provide more room to fit other aircraft. At first, the plan was rejected due to the lack of metal allocated for the war effort. When George proposed constructing the hangar of wood, which was considered a “non-strategic material”, and built a scale model to demonstrate the structure of this hangar, the plan was approved, and on May 1st, 1943, ground was broken for the new 138 feet by 150 feet hangar. Local trees were felled to collect lumber for the project, and in order to lessen the strain on the wartime rationing of metal, the hangar’s metal components were built using metal from local scrap drives, including junked cars. The large hangar, later named the White Hangar, was officially dedicated on June 28, 1944, at a cost of $15,000 (around $276,115 in 2025 currency). By this time, however, the 305th College Training Detachment would cease operations at Fayetteville just two days later of June 30, as dedicated military airfields were now training a sufficient number of airmen for the war effort, just as the war was now firmly in the Allies’ favor. In all, more than 2,700 flying cadets were trained at Fayetteville Airfield from 1939 to 1944.

After WWII ended in 1945, Fayetteville Airport was officially renamed Drake Field in honor of Professor Drake on April 14, 1947. The White Hangar was now occupied by Fayetteville Flying Service, and over the next 50 years, Drake Field became a hub for commuter airlines flying in northwest Arkansas, such as Central Airlines, Frontier Airlines, and Metro Airlines. A local carrier, Scheduled Skyways, was even based out of Drake Field until the airline’s merger with Air Midwest. By the 1980s, though, with commuter services being moved to Northwest Arkansas National Airport (XNA), about 20 miles northwest of Drake Field, the airport became less busy and was often used more for private and general aviation flights, and on September 8th, 1999, the last commuter airline had moved its facilities to Northwest Arkansas National Airport.

In late 1985, local aviation enthusiasts decided to form an aviation museum ahead of the 150th anniversary of Arkansas’ statehood. With the approval of the then-mayor, Marilyn Johnson, volunteers worked to restore the old White Hangar, and in August 1986, the Arkansas Air Museum was officially opened. Among the museum’s first board of directors were Ray Ellis (founder of Scheduled Skyways), Bob and Jim Younkin, Floyd Carl, Jim McDonald, Larry Browne, Ernest Lancaster, and Bob McKinney. 21 years later, in 2007, the Ozark Military Museum (originally founded in Springdale as the North West Arkansas World War Two Museum) moved into a hangar next door to the Arkansas Air Museum. This collection of military ground vehicles would later merge with the Arkansas Air Museum in 2012, forming the current-day Arkansas Air and Military Museum.

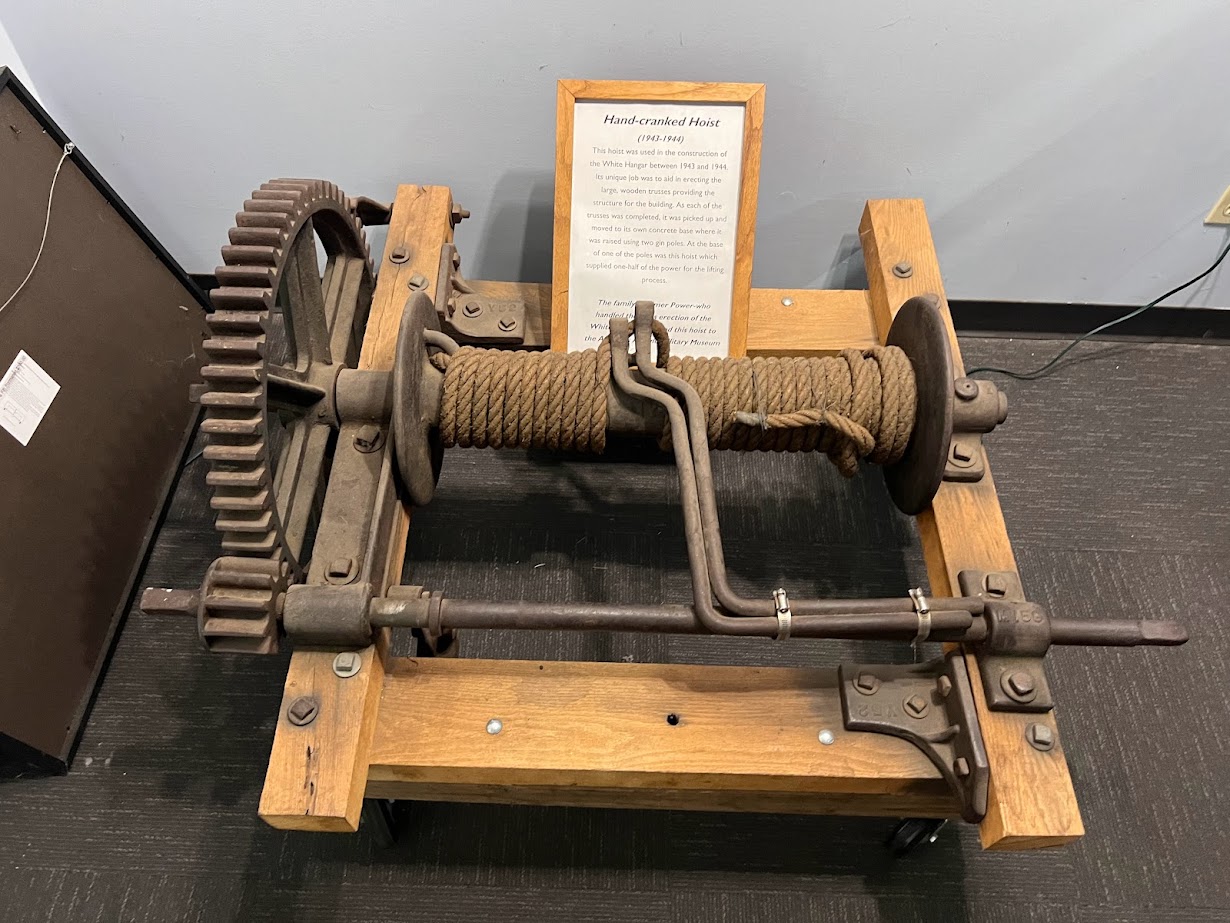

Located right on U.S. Route 71, visitors enter and exit through a doorway on the west end of White Hangar, where they will find a number of exhibits on the creation of Drake Field and on U.S. military history from the First World War to the Vietnam War, with mentions of prominent Arkansans, such as WWI ace Field Eugene Kindley (1896-1920) and James Oden, who served in the Army as an artilleryman in WWII and Korea before flying Sikorsky H-34 helicopters in Vietnam. Part of the exhibits on the creation of Drake Field include a hand-cranked hoist used to erect the large wooden trusses that still hold the hangar up to this day, some 80 years after its construction.

Upon entering White Hangar, visitors will come across a number of aircraft and aviation-related artifacts displayed under the trusses of the wooden hangar. Among the first aircraft present is a Stinson Junior S, registration NC12143 that was restored and flown by one of the founders of the Arkansas Air and Military Museum, Jim Younkin, a professor of engineering at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville who designed autopilot systems and other flight instruments still used in aviation today, and a major figure in the Vintage Aviation and Sport Aviation communities. On the other end of the hangar sit a flying replica of the Travel Air Type R “Mystery Ship” built by Younkin in 1979, using original factory drawings of the racer developed in secrecy before its public debut at the 1929 National Air Races in Cleveland, Ohio, where it was just as, if not faster than many of the fighters flown by the U.S. military at the time. The major differences in Younkin’s Mystery Ship from the original five built were that he used a Lycoming R-680 radial engine in place of the original Wright R-975 Whirlwind and a tail wheel in place of the original tail skid.

Next to the Younkin Mystery Ship is Learjet 23 N23BY, only the ninth example to roll off the production line in 1965. After flying for several private owners under the registrations N5BL and N13SN, this Learjet was acquired by Bobby Younkin, Jim Younkin’s son. Along with other aircraft, Bobby Younkin would perform aerobatic routines at airshows in Learjet 23 N23BY and earned sponsorships from aviation businesses such as Hale Aircraft, Inc., and Dodson International. Tragically, Bobby Younkin lost his life in 2005 during an airshow performance with his friend and fellow pilot Jimmy Franklin, but Bobby’s son Matt continues the legacy of his father and grandfather and can still be found performing at airshows across the U.S. to this day.

Perhaps the rarest aircraft inside the White Hangar is the last surviving example of a Howard DGA-18. Developed by Benny Howard, the founder of Howard Aircraft Corporation, who gave his airplanes the code DGA for “Damned Good Airplane”, the Howard DGA-18 was designed as a two-seat trainer specifically for the Civil Pilot Training Program. The DGA-18 could operate with a 125 hp seven-cylinder Warner Scarab radial engine, a 160 hp five-cylinder Kinner R-5 radial engine, or a 145 hp Warner Super Scarab, an updated version of the original Scarab engine, with these variants being designated the DGA-18 (or DGA-125), the DGA-18K (or DGA-160), or the DGA-18W (or DGA-145), respectively. Construction consisted of a tubular steel fuselage frame with metal panels on the forward section and fabric covering from the rear cockpit to the rudder. The wings were made from plywood spars, ribs, and panels covered in fabric. Once pilots in the CPTP qualified on the Piper Cub, it was intended that they would complete secondary training in the DGA-18 series before transitioning to more advanced aircraft. Many of these aircraft were, in fact, flown out of Fayetteville Airport with the CPTP during the war. Approximately 60 or so DGA-18s were built, and of these, the example on display at the Arkansas Air and Military Museum is the last known surviving example of the type, which is a Kinner-powered DGA-18K (DGA-160), construction number 668, registration number N39668, which was donated to the museum by Robert Gast of Steger, Illinois.

The White Hangar is also home to two homebuilt replicas of WWI fighters, with a replica of a Nieuport 11 and a Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a, both powered by modern inline engines. The hangar also contains a North American SNJ-5 Texan, Bureau Number 51968, FAA N-number N3263G, which was formerly displayed at the National Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida, and aboard the USS Yorktown (CV-10) at Patriots Point, Charleston, South Carolina. Another naval aircraft in the museum is Piper J-3 Cub N20830 (c/n 2130), which is presently on loan from the National Naval Aviation Museum and is presently marked as an NE-1 Cub flown by Airship Squadron 32 (later Blimp Squadron 32 (ZP-32).

On one of the walls of the White Hangar, a rare wing section from a Curtiss R3C Army/Navy racer is on display, complete with the evaporative cooling radiator panels installed on the wing for better streamlining. The White Hangar is also home to several aircraft that evoke the spirit of general aviation, from a Curtiss-Wright CW-1 Junior, suspended from the ceiling with no fabric in order to show its skeletal frame, and a Pietentol Air Camper, one of the earliest homebuilt kit design aircraft. Like many early models of this design, it was powered by a Ford Model A engine, a Bensen B-8 Gyrocopter, and a Piper Tri-Pacer.

Sitting outside between the museum’s two hangars is a Lockheed C-130H Hercules, 86-0410. Previously assigned to the 758th Airlift Squadron of the 911th Airlift Wing, this Hercules’ last active assignment was with the 154th Training Squadron of the Arkansas Air National Guard before being donated to the museum as the Arkansas ANG retired the last of its four-bladed H model C-130s. Visitors can enter the aircraft’s cargo bay through the open loading bay.

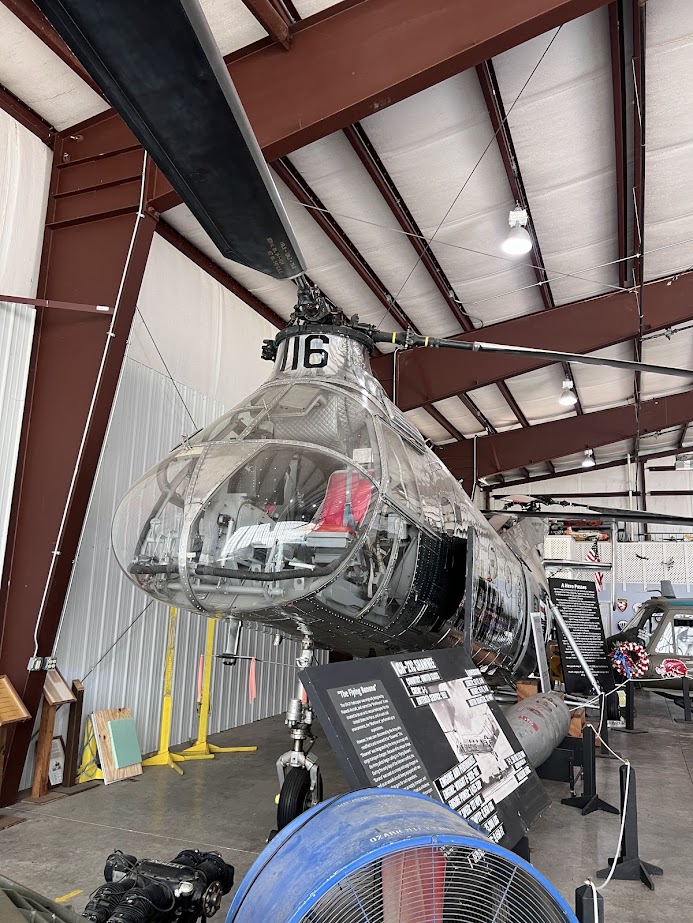

In addition to the White Hangar, the former Ozark Military Museum hangar houses both ground vehicles, such as Jeeps, trucks, and even a British Ferret armored car, and further aircraft in the museum’s collection. A single Bell AH-1S Cobra, serial number 67-1581,7, and two Bell UH-1 Iroquois/Hueys are on display in this hangar, and one of these UH-1H 65-12882 is accessible to visitors through the sliding doors to the passenger/cargo cabin immediately behind the cockpit. Two other helicopters on display are two examples of the Piasecki H-21 Shawnee, better known as the “Flying Banana”. These two CH-21Cs, serial numbers 55-4154 and 56-2116, were recovered from a scrapyard in Alaska by Max Hall, a local veteran who had previously been an Army H-21 helicopter pilot. While 56-2116 sits inside the hangar, its polished bare metal gleaming, 55-4154 sits outside but is open for visitors to explore its cabin.

Meanwhile, this hangar also houses a Boeing-Stearman PT-17 (US Army Air Force serial number 41-8575, FAA N-number N5682) painted as a US Navy N2S-2 trainer, and two liaison aircraft, an Aeronca L-3, N47365, and a Stinson L-13A, serial number 47-275. There are also exhibits focused on Drake Field’s history as a commuter aircraft, with artifacts from airlines that once served the airport as part of their regular schedules. Lastly, a group of former military jets can be seen sitting outside, facing U.S. Route 71. These are the museum’s Lockheed T-33A, USAF s/n 56-1673, North American T-2C Buckeye BuNo 158880, Ling-Temco-Vought A-7B Corsair II BuNo 154523, and Douglas A-4C Skyhawk BuNo 147733.

Should you find yourself in this beautiful and scenic part of Arkansas, the museum is open from 9am to 4pm Tuesdays through Saturdays, being closed on Sunday and Monday. Admission is $11 for adults, $6 for children between ages 6 and 16, and free admission for children under the age of 5.

To learn more about the Arkansas Air and Military Museum, visit the museum’s website HERE.

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.