As one would expect, the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio, the museum also displays a number of aircraft flown by nations that have fought the United States in aerial combat, be it the museum’s Halberstadt CL.IV German WWI reconnaissance bomber to the museum’s various Russian-built fighters developed by Mikoyan-Gurevich and Sukhoi. Perhaps the most prominent area of the museum where enemy aircraft can be seen is the WWII gallery, where German, Japanese, and even Italian aircraft share the gallery with aircraft flown and maintained by the U.S. Army Air Force. The largest of these is one of the last intact examples of a German twin-engine bomber, a Junkers Ju 88. Instead of wearing the swastika or the Balkenkreuz, though, this Ju 88 carries the colors of the Royal Romanian Air Force, and the story behind how it came to reside in Dayton, Ohio is perhaps one of the most fascinating yet little-known stories of World War II aviation history.

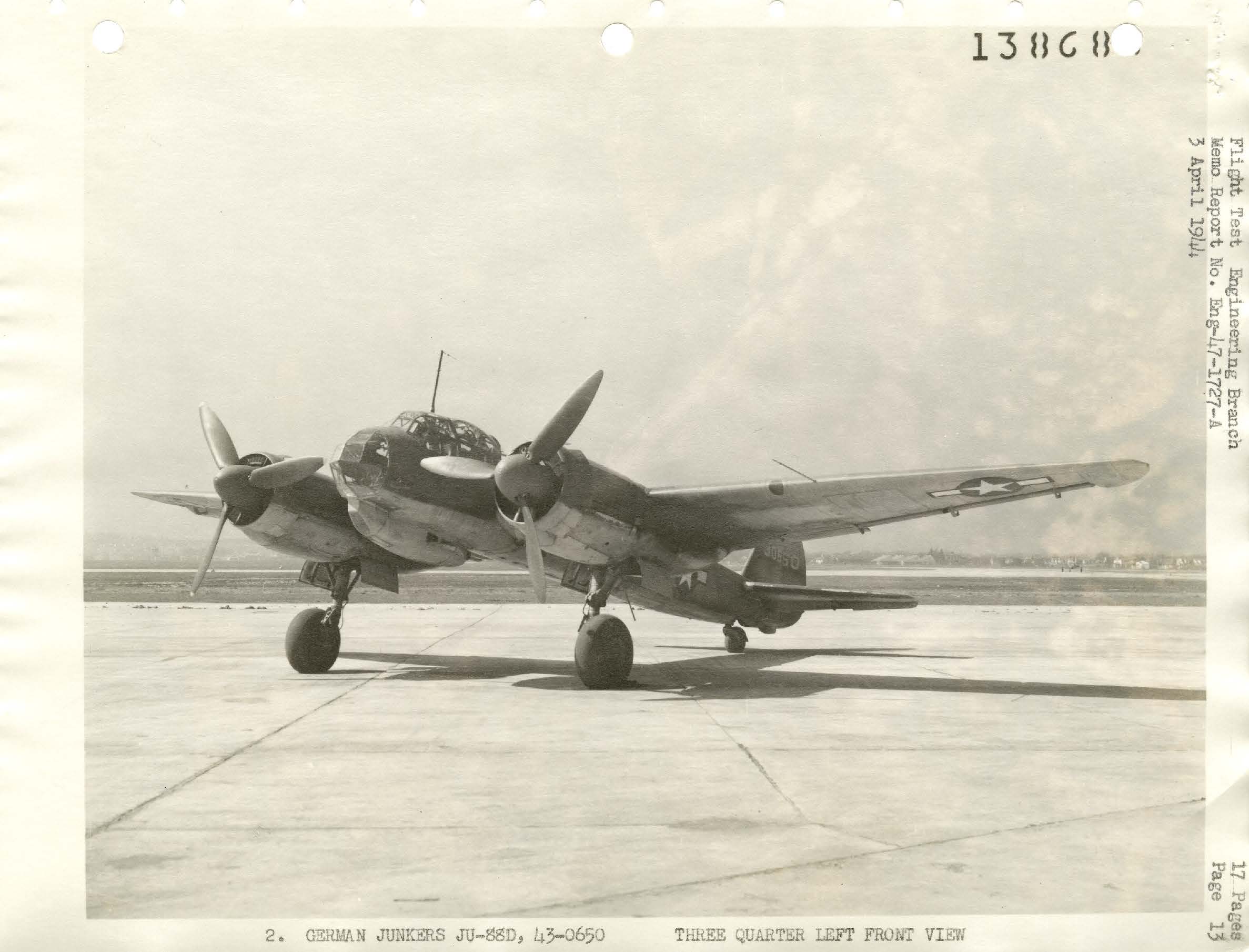

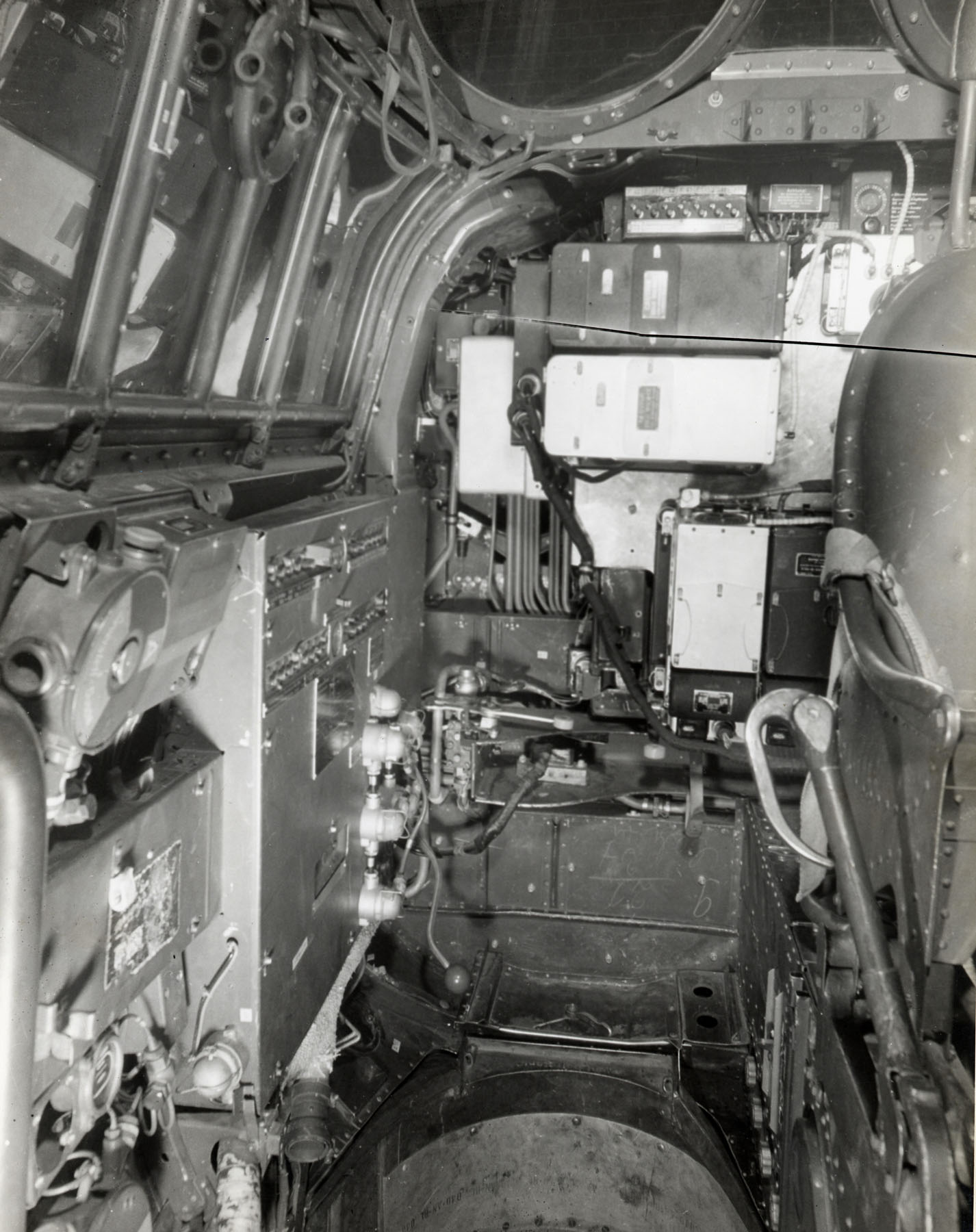

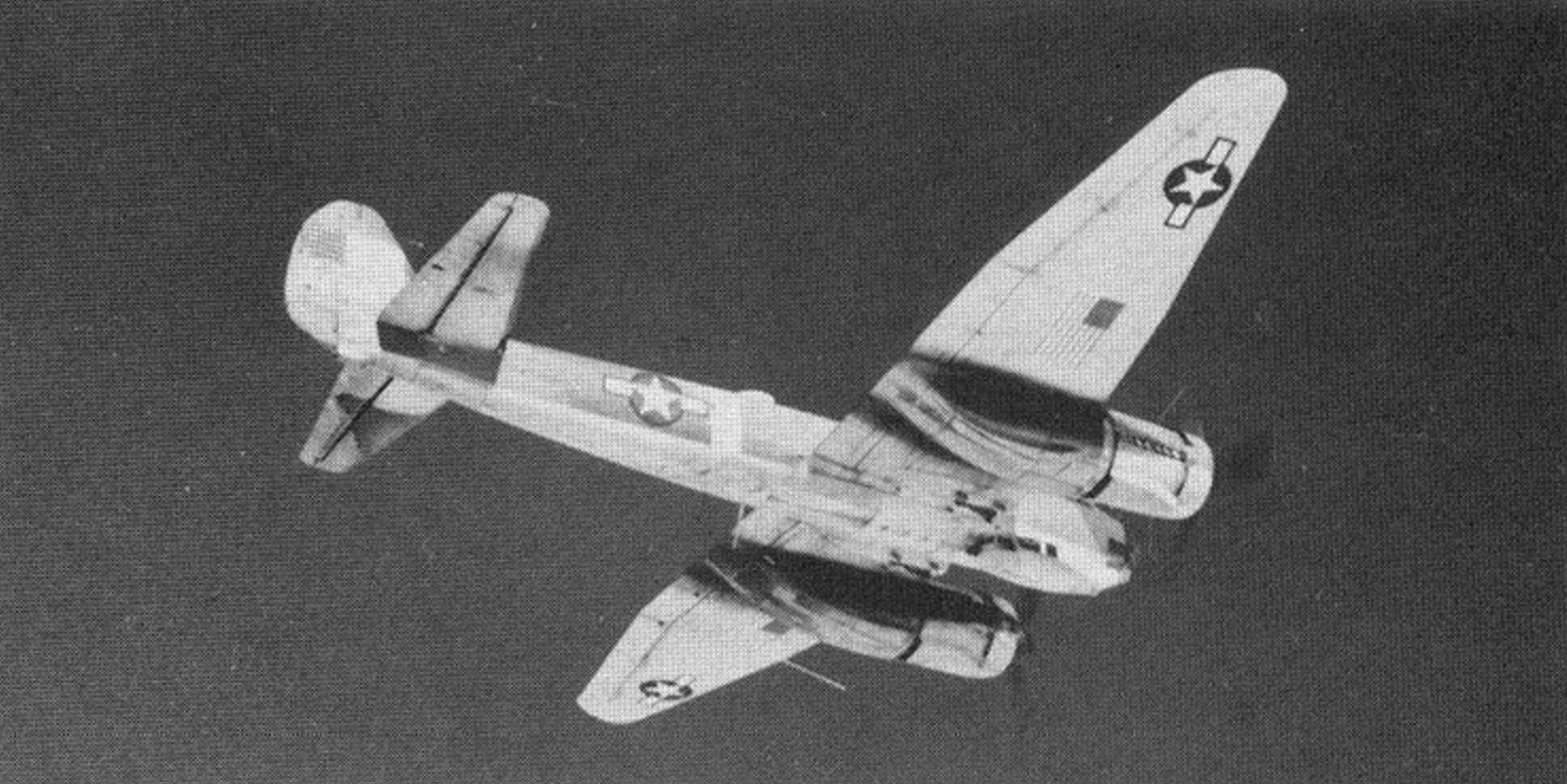

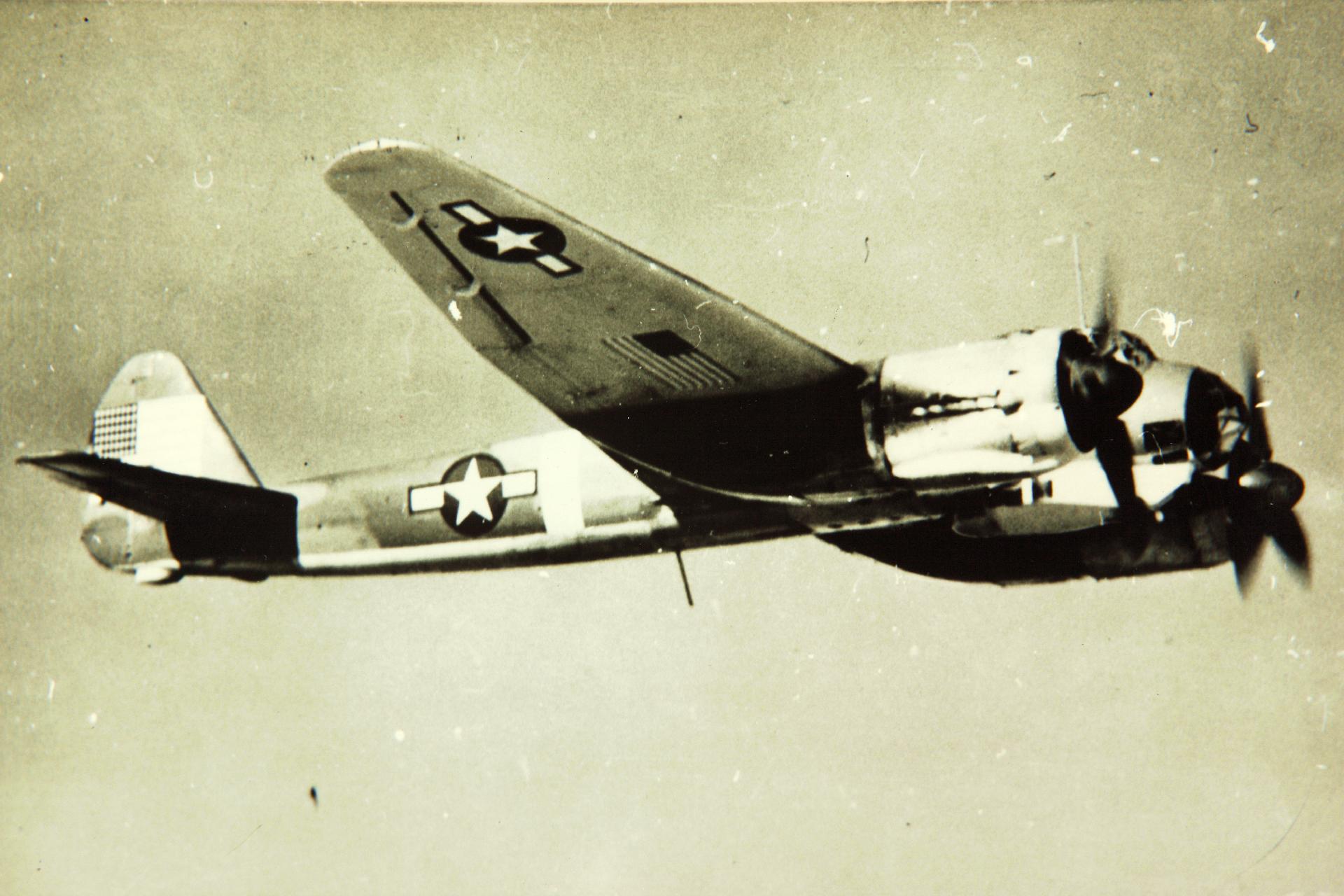

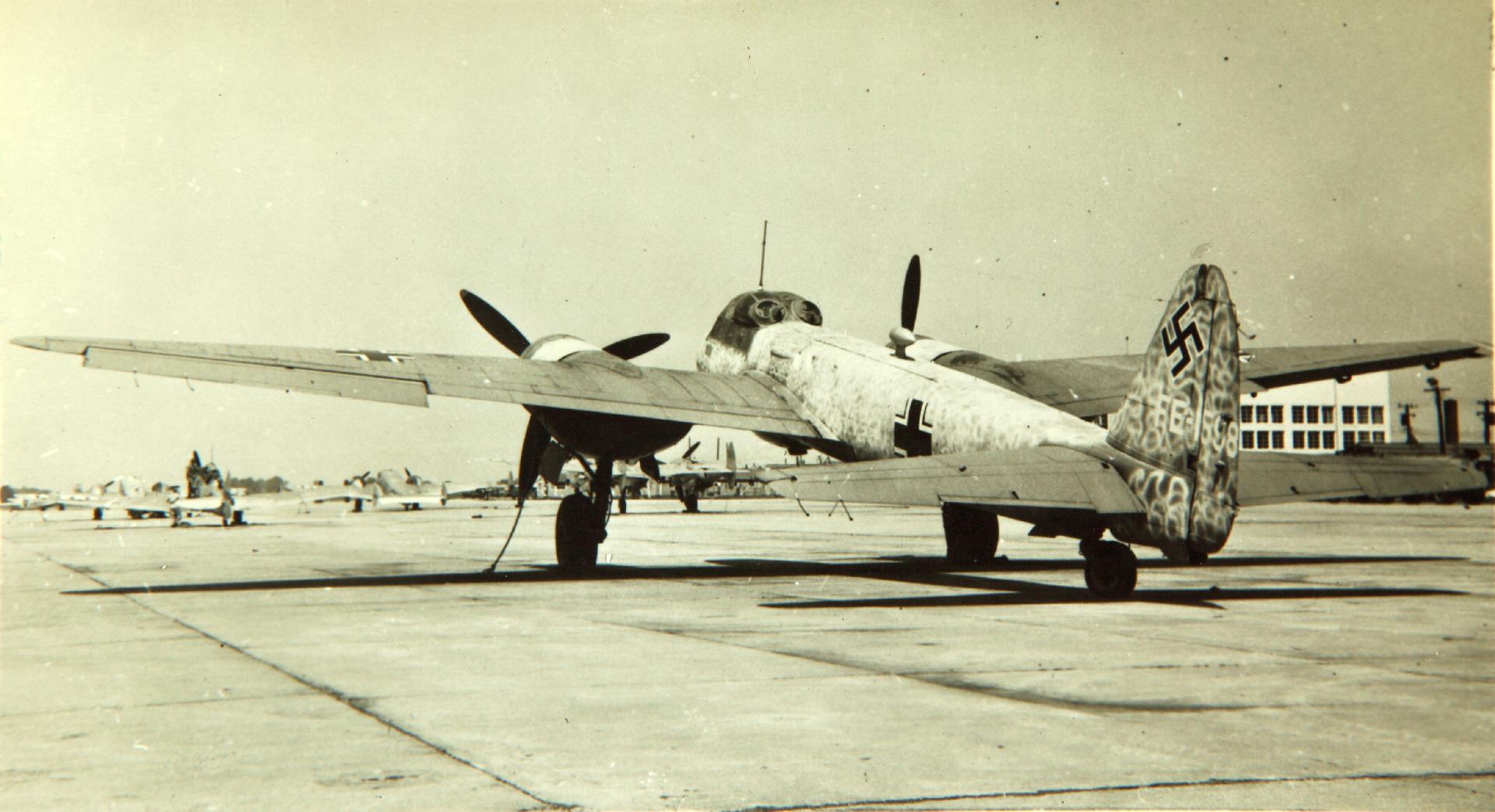

Since the wider story behind the Junkers Ju 88 bomber has previously been covered by Vintage Aviation News in this article HERE, we can start this story with the construction of this aircraft. Built in Germany in June 1943, the aircraft was issued the Werknummer (WNr.) 430650 and built as a Ju 88D-1 photo-reconnaissance aircraft. As a recon aircraft, WNr. 430650 was with camera equipment, had its dive brakes omitted, and could carry two drop tanks from the external bomb racks on the undersides of the wing center section. Each fuel tank had a capacity of 900 liters (238 gallons), complementing the capacity of the plane’s internal fuel tanks (3,580 liters (946 gallons)). The combined fuel capacities offered the aircraft a maximum range of 5,000 kilometers (around 3,100 miles).

Additionally, WNr. 430650 was fitted with sand filters for the oil coolers on its Jumo 211 engines, becoming a Ju 88 D-1/Trop. (Tropicalized variant; later redesignated as a Ju 88 D-3). Sand filters were frequently used on German aircraft shipped to the North African and Mediterranean theaters of operations, but were also useful for operating from unpaved airstrips on the steppes of Ukraine and Russia.

By this point in the war, the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM; German Air Ministry) allowed for the export of fifty Ju 88s to the Aeronautica Regală Română (ARR, ’Romanian Royal Aeronautics’), as Romania was allied with the Germans against the Soviet Union, and was in the process of replacing the licensed-built version of the Savoia-Marchetti SM.79B, the IAR-79. Thus, a number of German flight instructors were sent to familiarize the Romanian crews with the Ju 88s, with WNr. 430650 being assigned to the 2nd Long Range Recon Squadron, 1st Long Range Recon Group, based at Mariupol, occupied Ukraine.

Among the pilots of the 2nd Longe Range Recon Squadron was a 29-year-old Nicolae non-commissioned officer named Nicolae Teodoru (referred to in some sources as Theodore Nikolai) By July of 1943, Teodoru had flown 11 combat missions, having taken photographs of Soviet positions while outrunning interceptors and anti-aircraft fire sent to prevent them from delivering their film for subsequent development and analysis.

Despite the censorship of information about the current progress of the war, Teodoru was already aware that the Axis Powers were now on the defensive. The Allies had driven the Germans and Italians from North Africa and landed in Sicily, and the Germans were involved in heavy fighting with the Soviets over the city of Kursk. Privately, Teodoru became disillusioned with the Axis, and what the outcome of a German defeat meant for Romania and thus hatched a plan to defect. Knowing he would not find sympathy with the Soviets, he sought to use one of his unit’s Ju 88s to escape to the western Allies.

Since the Ju 88 had a single set of controls, Teodoru planned to use the excuse that he was taking the aircraft for a solo test flight and hopefully fly far out of range for interceptors before his cover was blown. In order not to attract any suspicion, though, he decided to take no maps or personal items with him on this flight, relying instead on dead-reckoning, compass readings, and calculations of his fuel supply and fuel consumption rate to guide him.

At around 3:00pm local time on July 22, 1943, Teodoru informed a sentry that he would take a Ju 88 for a test flight. The aircraft he chose was tail number White 1, Ju 88D-1/Trop., Werknummer 430650. Upon climbing into the cockpit through the ventral turret’s entry hatch, Teodoru started the engines, then taxied to the runway and took off. From outward appearances, it appeared to be just another routine test flight to ensure the aircraft was in working order. By the time he had flown out of visual range of his former comrades, Teodoru managed to put enough distance between him and the German/Romanian airfield in Mariupol to be out of range for any interceptors.

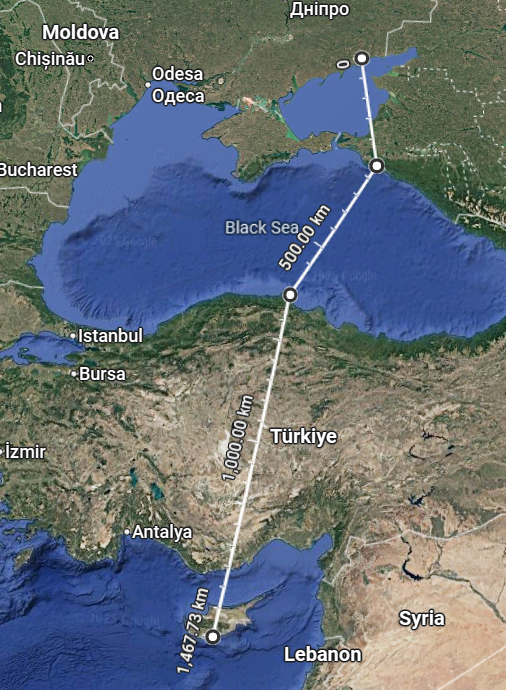

Soon, Teodoru turned south and flew across the Sea of Azov, taking his bearings over the Russian Black Sea port of Novorossiysk. This being accomplished, he descended to near wave-top level over the Black Sea, and made landfall near the Turkish city of Sinop, some 300 kilometers (186 miles) northeast of Ankara. From there Teodoru climbed to 10,000 feet and entered a dense cloud bank, obscuring him from potential Turkish interceptors and anti-aircraft fire.

Flying on instruments through the clouds, Teodoru hoped to fly over Turkey and Syria to land in Beirut, Lebanon, then occupied by Free-French forces. But unbeknownst to Teodoru, he had been blown off course by an easterly cross-wind while in the clouds, so when he emerged expecting to find Beirut, he was instead miles off course over the eastern Mediterranean Sea with no land in sight and his fuel running low.

Then, Teodoru spotted land, which turned out to be the island of Cyprus, then under British colonial rule. As he approached from the north at around 7:00pm, four Hawker Hurricane Mk IIBs of No. 127 Squadron, RAF from RAF Nicosia spotted the lone Romanian Junkers during their evening patrol. Teodoru was fortunate in that he had lowered his flaps and landing gear and reduced his throttle just as the Hurricanes came out of the clouds. Seeing that the bomber had its gear and flaps down and being unfamiliar with the Romanian markings on his plane, the four Hurricanes formed up on Teodoru, with three of them close to his tail, and the fourth led him from the front.

The Hurricanes of No. 127 Squadron escorted the Ju 88 to the RAF base at Limassol, on Cyprus’ south coast. They stuck with him so closely that they nearly landed alongside him, peeling away only when his wheels touched the runway at 7:15pm. After getting his plane on the ground, Nicolae Teodoru taxied the Ju 88 to the flight line, switched off the two engines, and calmly climbed down from the cockpit to turn himself in as a prisoner of war. According to an Air Ministry Weekly Intelligence Summary dated September 11, 1943, the Ju 88 landed at Limassol with just enough fuel for only 10 minutes of flying.

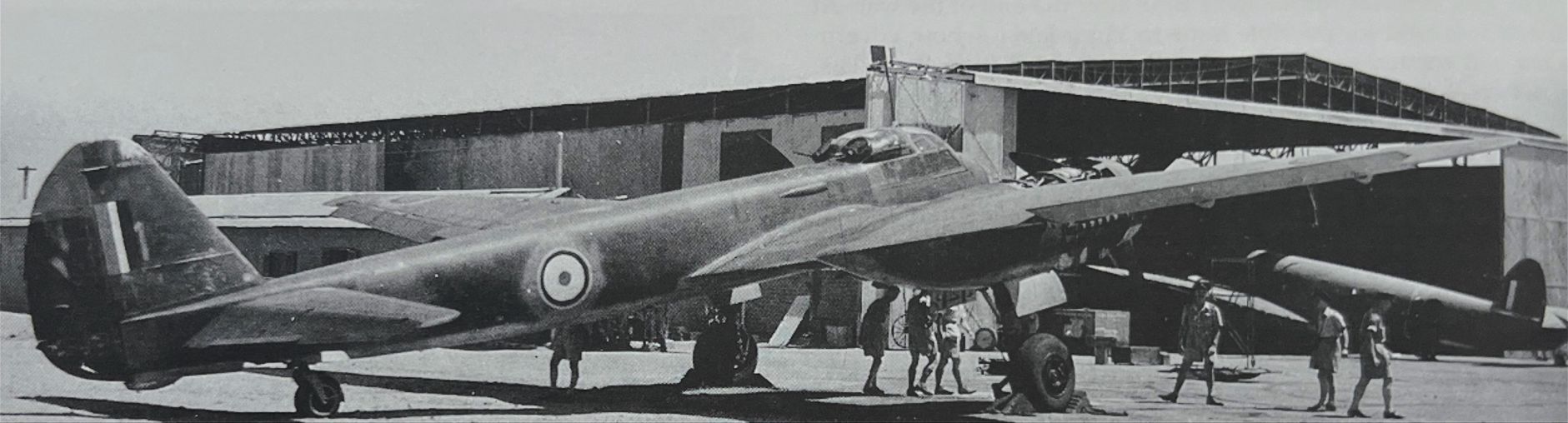

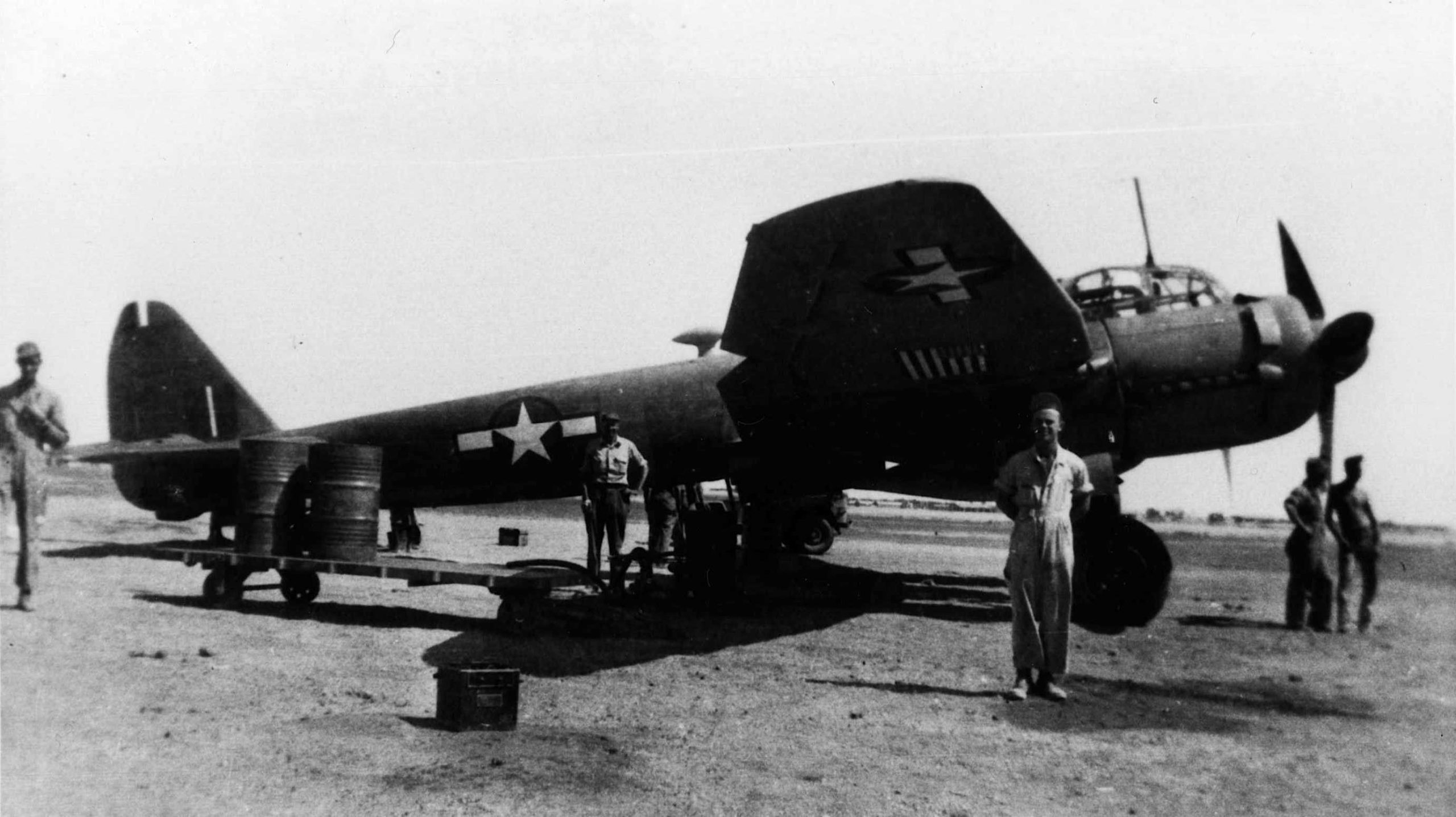

While it was not the first time a Junkers Ju 88 had come into Allied hands by a defecting crew, it was still a boon for air intelligence units. The aircraft itself was in mint condition, and still had less than 50 flight hours logged. Soon, an RAF test pilot was brought out to Cyprus, where the Ju 88 was given a hasty RAF desert scheme, and with Nicolae Teodoru willing to cooperate with Allied officials, the aircraft was flown on July 27 to RAF Heliopolis, located in the Heliopolis district of Cairo, Egypt. It was subsequently assigned to No.1 British Airways Repair Unit (No. 1 BARU) and allocated the RAF serial number HK959 for technical evaluation.

By this point, the RAF was already testing a radar-equipped night fighter variant of the Ju 88, Ju 88 R-1 WNr. 360043 (RAF s/n PJ876), which had been defected from a Luftwaffe base in Kristainsand, Norway to RAF Dyce (now Aberdeen International Airport), Scotland, on May 9, 1943, with two of crew having brought an unwitting third crewman held at gunpoint. The night fighter proved especially valuable in that it helped the British come up with ways to contact and jam German radar. As the Americans had yet to evaluate any German twin engine bombers inside the continental U.S., the RAF decided to transfer HK959 to the US Army Air Force. But with the aircraft still sitting in Heliopolis, the aircraft would have to go on a 12,000-mile flight to the United States.

On October 1, 1943, two airmen at the end of their duty of duty arrived at Payne Army Airfield (now Cairo International Airport) to begin their long journey home. They were Captain Warner E. Newby and Lt. George W. Cook of the 81st Bombardment Squadron, 12th Bombardment Group, Ninth Air Force. In July 1942, both men had flown the South Atlantic ferry Route in their B-25 Mitchells, and had flown bombing missions over North Africa with Newby being a pilot and Cook being a flight engineer.

In the last six months off their tours, Newby and Cook had been assigned non-combat roles at the 26th Air Depot Group (ADG) at RAF Deversoir on the western side of the Suez, about 70 miles (113 kilometers) from downtown Cairo, with Newby serving as the Depot Engineering Officer. Now, they had been summoned to John Payne Field (now Cairo International Airport), which was adjacent to RAF Heliopolis, and found themselves waiting for an Army Air Force transport to become available for them to board.

While waiting, they spotted an official notice calling for volunteers to fly an airplane back to the United States. This did not specify which aircraft was to be flown back to the States, and only listed a phone number for contact, but Newby and Cook figured it would be better to fly their own plane back home than becoming two passengers on a long light home. Soon, they were told to wait for a staff car to pick them up and take them to Ninth Air Force headquarters. On meeting with intelligence staff officers, they were interviewed about their flight experiences, where they were informed that a highly qualified flight crew with a strong technical background was required for a special project. Upon the conclusion of their interviews, Newby and Cook were told to wait and have lunch at the Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo before being summoned to return at 1:00 pm.

Upon returning, Newby and Cook were finally informed that they would be flying the Ju 88 bomber at RAF Heliopolis to the United States in order to undergo technical evaluation at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio. Later that day, they arrived at Heliopolis, where they were greeted by 58-year-old RAF wing commander Charles Sandford Wynne-Eyton, who had served in WWI as both an artillery officer and as a pilot and had spent the Interwar Years in Rhodesia and Kenya. Wynne-Eyton led the two Americans on a walk-around inspection of the Ju 88 before taking them for a check ride. After this brief instruction, Newby and Cook flew the Ju 88 back to Deversoir to begin preparations for the flight to America.

It was also around this time that Newby and Cook gave the Ju 88 a new name: Baksheesh. In Persian, this word has several meanings, from bribe to tip to gift. American servicemen often heard street beggars calling out this word when asking for spare change. Newby and Cook came to define the phrase as meaning “something for nothing”. To them, the Ju 88 was a gift from the Führer.

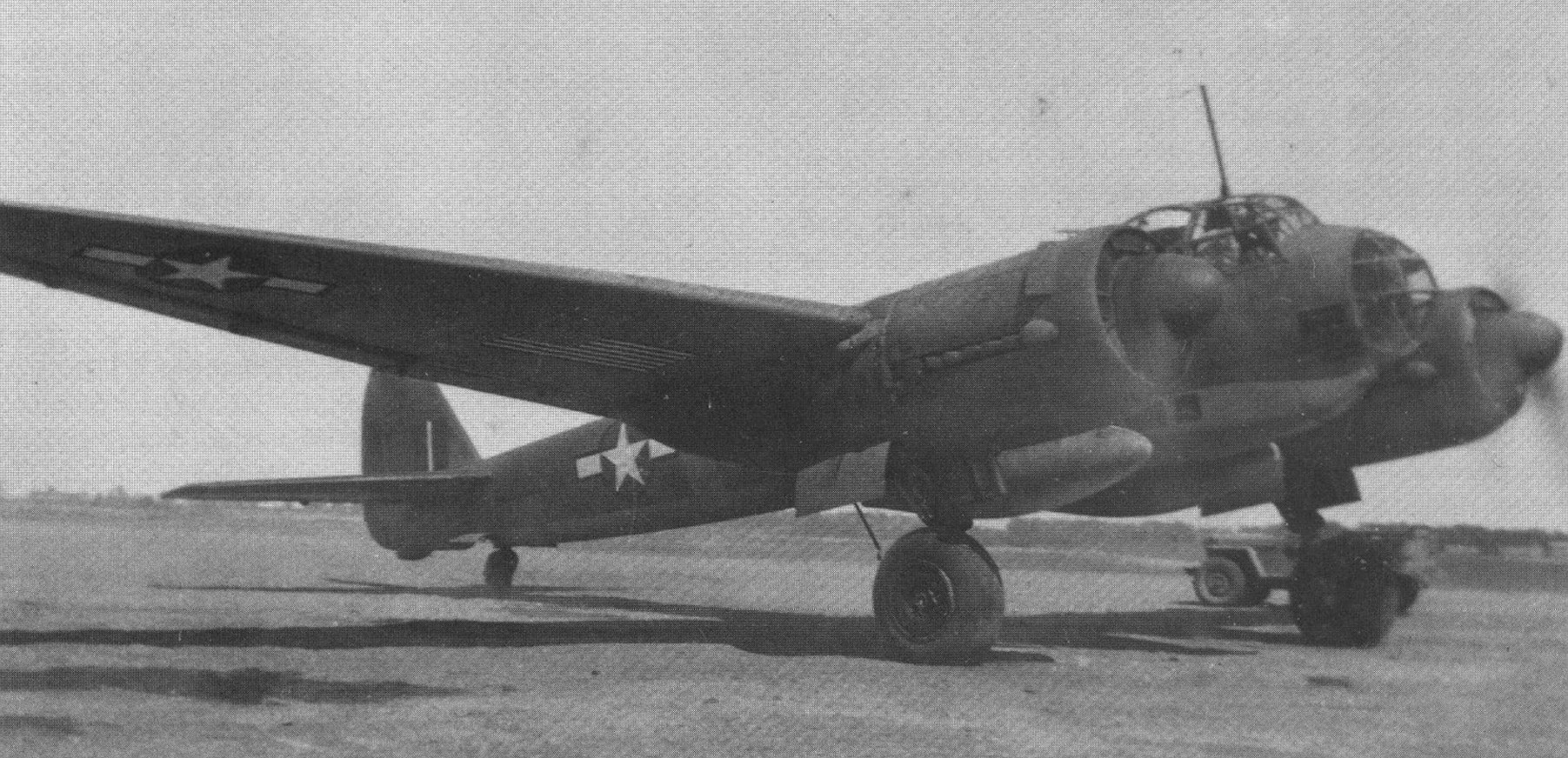

After a week of modifications, Newby and Cook, with the help of six enlisted mechanics, a Consolidated Aircraft engineer, and a General Electric technician, serviced the aircraft, calculated its range, fuel and oil consumption rates, installed a pair of P-38 Lightning drop tanks, added the fuel transfer system from a Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber and an ARN-7 radio compass to get a fix on Allied radio frequencies, and replaced the German inflatable life raft for an American model. While working on the aircraft, they also learned from fuel analysts that 87-octane was most compatible with the engines, but that 91-octane fuel would be the most readily available grade along their journey. The aircraft was also repainted to wear prominent American flags on its wings, fuselage, and tail, along with standard USAAF roundels.

One incident that occurred on the ground at Deversoir would instill a painful lesson, though. Flight engineer George Cook decided to test the drop tank jettison system, which was also the same system used to drop externally mounted bombs. With Cook and a few mechanics standing under the right-hand drop tank, Newby flipped the switch labelled “bomb release”, and a loud bang and smoke filled the air, along with shouts of pain. The right drop tank was still on the rack, but Lt. Cook and two sergeants were injured by shrapnel, while the left drop tank was now laying on the flight apron. As it turned out, when Baksheesh had been constructed, the wiring for the bomb/drop tank racks had been inverted, and the jettison system used explosive bolts. Fortunately, the three wounded men had only minor wounds that were soon treated, and the electricians on the base disconnected the release switches and isolated the wires. They would now have to carry to the drop tanks throughout the flight. By the morning of October 8, 1943, eight days after they first saw the Ju 88, Captain Newby and Lieutenant Cook were at last ready to take the Junkers across the Atlantic. The right engine came to life immediately, but the left engine ran rough, got to 1,000 RPM, then stopped. The cause was an oversized cotter pin inside a clevis pin, which jammed the automatic fuel valve. The issue was soon fixed, though, and the crew made one more test flight.

On takeoff, the aircraft proved slow to lift off the runway, and they brushed the tops over several date palms 1,000 feet past the end of the runway. The German-language instrument panel had made it hard for them to realize that the flaps had been in the retracted position at takeoff. After feathering and restarting both engines in flight, testing the ARN-7 radio compass and monitoring the fuel transfer systems, Newby and Cook landed back at Deversoir at sound 11:00am. Following their final inspection, they were set to begin their long flight when Captain Newby received both a sealed and an unsealed envelope. The unsealed one contained the flight orders to fly the Junkers Ju 88 to Wright Field and deliver it to Colonel Oliver “Olie” Hayward of the Air Technical Intelligence Center, and stated that they were not to leave Africa until October 10, which was also the date that Newby had to wait for before opening the sealed envelope. The unsealed envelope also stated that the Ju 88 would be issued the serial number 43-0650 (based on its German Werknummer).

At noon, Warner Newby and George Cook began their flight out of Deversoir, with orders to fly to Khartoum, Sudan. They set flaps to 25 degrees and got off the ground much sooner than their prior flight that day. From there, Newby and Cook cruised south at 9,500 feet, following the Nile River upstream to Khartoum. Four hours and twenty minutes after taking off from RAF Deversoir, Baksheesh and her crew landed at Khartoum, 1,035 miles south, and spent the night there.

On October 9, Newby and Cook took off from Khartoum at 4 am local time. Five hundred miles from Khartoum, Newby and Cook took their bearings over the city of Al Fashir and turned west for their next stop: Maiduguri, Nigeria, 849 miles west of Al Fashir. After their five-hour flight from Khartoum, Newby and Cook landed at Maiduguri, attracting a large crowd of both Allied personnel and Nigerian locals as the aircraft was refueled for the next leg of the flight that day. Upon hearing of optimal flight conditions, they decided to head to their next stop, 1,012 miles further west: Accra in modern-day Ghana. On the flight to Accra, Newby and Cook overtook a Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express, a transport variant of the B-24 Liberator bomber, about 75 miles out from Accra. With no other air traffic in this region, the two crews spoke to each other freely over the radio to pass the time until the Ju 88 landed at Accra first. Once again, a crowd gathered to see the Junkers as Newby and Cook closed their flight plan and prepared for the next day’s flight.

The next leg out of Accra would be one of the most challenging ones of the flight. They were to land on Ascension Island, some 1,357 miles southwest, with nothing but the vast expanses of the South Atlantic Ocean below them. The British-held island served as a vital outpost for anti-submarine operations and for the transit of Allied aircraft across the South Atlantic. As they plotted their course in Accra, the pilot of the C-87 approached Newby and Cook and offered to fly ahead of the Ju 88, as Newby and Cook had no navigator with them, while the C-87 crew had one. Newby and Cook agreed to this, though the Ju 88’s cruising speed proved faster than the C-87’s maximum speed in level flight. Nonetheless, when they compared their charts, the two crews had nearly identical approaches into Ascension.

On waking up at 3:30 in the morning on October 10, Warner Newby finally opened the sealed envelope he was given at Deversoir, which revealed that he was to be promoted in his operational theater rank from captain to major, and was given the oak leaf insignia to add to his flight uniform. Later that morning, the Ju 88 and the C-87 took off in close intervals and headed out over the Atlantic. After maintaining the same heading for nearly an hour, Newby radioed the C-87, saying they would have to increase their airspeed. After the C-87 confirmed their heading, Newby thanked them for their help, and the Ju 88 crossed the Equator 05° 05′ west longitude one hour and 45 minutes into the flight.

One of the most dramatic moments in the flight occurred, as recollected by Newby in his 1944 article for the January 1944 issue of Air Force, the official service journal of the USAAF: “Suddenly there was a loud rustling of wind, and cold air struck me on the shoulder. I looked around and saw Lieutenant Cook, white and scared stiff, looking down through the hatch which had come open when he accidentally brushed against the safety latch. The little Irishman was standing there, without any parachute, over a big opening in the bottom of the fuselage, and the only thing that had saved him was the fortunate position of his feet. Luckily, he was able to brace himself and grab a fuselage cross strut. After struggling with the hatch for a few minutes, he finally got it closed.” Soon after this incident, Newby noticed a vapor trail coming off the left wingtip. The two airmen figured out that when Cook was transferring fuel in the wing, the hatch for the vent line at the wing tip had opened. Cook then shut off the fuel transfer, and the vapor trail disappeared about a minute later. As they were getting closer to Ascension Island, Newby and Cook saw before them a formation of Douglas A-20 Havocs heading eastbound to make their first stop in Africa. One of the Havocs split off from the formation and came in to make a close circle around the unfamiliar aircraft. Newby and Cook waved back from the cockpit of the Ju 88, and as they continued westward, the Havoc proceeded to rejoin its formation. Sometime after this, Newby and Cook began picking up the radio beacon from Ascension Island, and the radio compass confirmed they were on the right heading.

As they scanned the Atlantic searching for any sign of Ascension, a pair of Bell P-39 Airacobras came up, making a fast swipe, and established radio contact with the Junkers Ju 88. One P-39 each paired up on the Ju 88’s wings, and the German bomber landed on the downwind approach at Wideawake Field (RAF Ascension Island), with the P-39s waving off to go around on their own final approach. It had been five hours, fifteen minutes from Accra to Ascension, and the aircraft had covered 1,373 miles on this leg of the flight to Dayton.

Soon, Major Newby went to base operations to prepare for the next leg of the flight, which was to take them to Parnamirim Airfield in Natal, Brazil, the easternmost airfield on Brazil’s Atlantic coast, and another key staging ground for both anti-submarine patrols and ferry flights to Africa. By their calculations, they could reach Natal 30 minutes before nightfall if they left Ascension within the next hour and a half. As they began to refuel, however, Lt. Cook was angry to discover that the island’s fuel depot had run out of 91-octane gasoline, with the lowest grade on hand being 100-octane. Though the wing tanks were still nearly full with 91 octane fuel, the two airmen had no choice but to fill the remaining tanks with 100 octane fuel. With that, they were off on the longest leg of their journey, with 1,420 miles between them and Natal, uncertain of how the higher-octane fuel would affect the two Jumo 211 engines.

Ten minutes after departing from Ascension, the last sliver of land disappeared behind the Ju 88. Cruising at 10,500 feet at a heading of 290°, the flight to Natal was uneventful for 3 hours and 45 minutes until the Ju 88 began to vibrate. Newby and Cook concluded that the 100-octane fuel was damaging the bomber’s two Junkers-Jumo engines. Just then, the front cylinder on the left bank of the right engine began spitting fire and sputtering loudly. Within a few minutes, the cylinder was dead and the two engines continued to run rough, with the crew still around 400 miles (an hour and a half of flight time) away from Natal, with no land or ships in sight as they continued their flight above the Atlantic, and being forced to reduce their cruising speed by around 10 knots. Nevertheless, the engines kept turning, and Major Newby and Lt. Cook pressed on. There was also the fact that when Cook read the fuel gauges on the engineer’s console, he saw that they had plenty of fuel to reach Brazil, with the wing tanks remaining full and with some fuel still left in the tanks fitted inside the bomb bay. Reassured of this, Newby nudged the throttles to pick up another 10 to 15 kph. Nonetheless, Newby ordered Cook to get everything ready in case they had to ditch in the sea, with the idea being that should that outcome become inevitable, they would do everything to reach shore or the shipping lanes for a better chance at rescue. They also debated whether they ought to jettison the P-38 drop tanks or keep them for extra floatation. But when they increased the power to the engines, the two airmen sensed that the engine vibrations began to lessen. Less than an hour out from Natal, Maj. Newby was confident that they would make it.

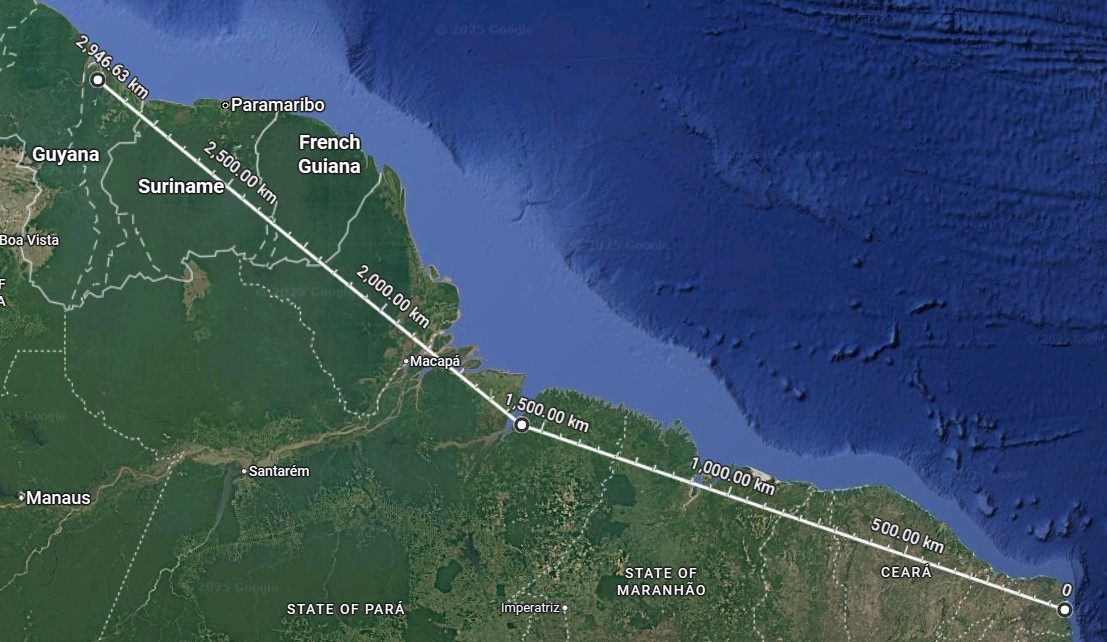

As the Brazilian coast drew closer, Baksheesh’s radio compass picked up the bearing for Natal dead ahead. Five hours into the flight from Ascension Island, the two airmen spotted the Brazilian coast, with Newby saying later that he understood how Columbus felt upon seeing land. The Junkers Ju 88 named Baksheesh was now the first German bomber to cross the Atlantic Ocean. A few minutes after sighting the coast, they found Parnamirim Airport (later named Augusto Severo International Airport after the war). Newby called the tower and informed them that they would begin their descent. The tower radioed back that a group of aircraft making a ferry flight to Africa via Ascension Island was heading out, and they would have to circle in a holding pattern for nearly 30 minutes for the air traffic to clear. As they got their clearance and made their final approach, the landing gear would only retract halfway down. After making several attempts to lower the gear, Lt. Cook found that the gear had very low hydraulic pressure, and used the emergency hand pump to manually crank the landing gear down to be locked in place after switching to the gear valve position. They circled the field one more time to get the landing gear locked in place, and on their final approach, Lt. Cook used the hand pump to partially lower the flaps while Maj. Newby brought the Junkers Ju 88 down for a hot approach, as if he was on a no-flaps landing. The Ju 88 touched down at Parnamirim, and after they taxied off the runway, parked the aircraft and shut down the engines, Maj. Newby and Lt. Cook went to close their flight plan.

In later writings, Warner Newby would attribute his and George Cook’s ability to handle the most challenging part of the flight in the Ju 88 with their time testing the aircraft’s systems at Deversoir, Egypt, before their epic flight began, which not only made them more familiar with the aircraft’s quirks but enabled to quickly troubleshoot problems like the ones they had going into Natal. With all of the issues they encountered, combined with the limited rest they had to endure with short nights and long days, Newby and Cook agreed to spend the following day at Natal to rest and fix any issues with the Ju 88 before proceeding on their journey. After securing the aircraft for the night, Newby and Cook took a shower and had dinner in the officers’ club, which they considered the best officers’ club they had been in since departing the United States. At 9:00 am on October 11, 1943, Newby, Cook, and the ground crews at Natal began work on the Ju 88. They fixed the hydraulic leak, cleaned the spark plugs on the two engines, and replaced the two on the troublesome front left bank cylinder. Additionally, they removed the P-38 drop tanks to reduce drag and drained the 100-octane fuel from the fuel tanks, replacing it with 91-octane fuel. Newby also learned that increasing the engine power on their flight to Natal was the correct move, in that it helped burn off the lead from the higher octane fuel. Soon after refueling the German aircraft, they ran the engines, conducted magneto checks, and tested the aircraft’s electric and hydraulic systems.

With all systems working, Newby and Cook went into town and bought some leather goods, with Newby having his newly-awarded oak leaves sewn onto his flight clothes before they would leave the next day for Belem, Brazil. On the morning of October 12, 1943, the Ju 88 took off from Natal and climbed to 10,500 feet at a heading of 292°. Their next stop, Belem, was a further 950 miles up the Brazilian coastline and near the mouth of the Amazon River. Newby felt that the Ju 88 was now more responsive with the removal of the drop tanks. Compared to the flight into Natal, the three-hour, 35-minute journey to Belem was more routine, but when they reached Belem and called the control tower for clearance to land, they could not establish contact. Twice, they were waved off on the final with their flaps and gear down and were forced to circle. Finally, Lt. Cook switched radio frequencies and got the Belem tower on an auxiliary frequency. The tower notified them that, due to a runway closure for repairs, base operations did not want them to land. Newby told the tower they had been advised of the repair work in their NOTAM (Notice to Airmen), which listed 4,000 feet of runway being available in spite of the repairs, and Newby could see other planes landing at the field. Newby also told the tower at Belem that they had no fuel to reach any other airfield, which were all several hundred miles from Belem. After being placed on standby, the base’s operations officer said he believed that the Ju 88 was too big to land in the amount of runway available, but informed them they could land at their own discretion. Newby demonstrated that the aircraft could indeed land in the amount of space available, and they pulled off at the first turnoff.

The two airmen had hoped for a quick turnaround at Belem on their way to Georgetown, British Guiana (now Guyana), as they were advised at Natal to get past the mouth of the Amazon before the afternoon buildup of clouds. The weather reports were favorable, but the base struggled to obtain a fuel truck with 91 octane fuel. After a long wait, the fuel truck finally arrived, and Newby and Cook took off two hours behind schedule. Around 15 minutes into the flight at a heading of 330°, they began to encounter a large layer of clouds and climbed from 10,500 feet to 12,500 feet. Soon after this, they reset the engine power to cruising speed, but then the right engine suddenly quit. Cook and Newby scanned the instruments and found that the fuel pressure in the right engine was low and that the fuel pressure in the left engine was both lower than normal and fluctuating. Newby activated the fuel booster pumps, and soon, the right engine restarted, and both engines ‘ fuel pressure began to stabilize back to normal. Flying at 12,500 feet also presented another challenge to the crew: although they had oxygen tanks and hoses, they did not have enough time to install any oxygen masks to the hoses while in Egypt, and they considered climbing to 14,500 feet to skirt the cloud ceiling;;they hoped to find a break in the clouds to allow them to fly lower. As they passed the Amazon, though, the heights of the clouds thinned out and after 30 minutes, they were able to descend back to 10,500 feet. By the end of the day, Baksheesh had landed near Georgetown at Atkinson Field (now Cheddi Jagan International Airport) and would stay there overnight before heading out in the morning.

On October 13, Newby and Cook took off in the Ju 88 from Atkinson Field, but when they found their throttle to be stuck, they went to Waller Army Air Field in Trinidad, about 350 miles northwest of Georgetown. After resolving this issue, they set off for Borinquen Field, Puerto Rico (later Ramey Air Force Base, now Rafael Hernandez International Airport), a further 673 miles away, having to fly around a tropical storm on their way. There, they refueled in order to arrive at their first stop in the continental United States: West Palm Beach, Florida. After taking off from Borinquen Field, the crew of Baksheesh radioed Miami and gave their ETA for entering the US defense zone. Miami instructed them to head directly for Miami, then follow the coast to West Palm Beach and land at Morrison Field (now Palm Beach International Airport). Upon landing and parking the Ju 88, a detachment of military police came up to Newby and Cook and asked them to remain with their aircraft until further notice as customs, immigration, and agricultural inspectors arrived on the scene, inspecting the aircraft and the men’s luggage while they asked the pilot and flight engineer questions about the nature of their flight.

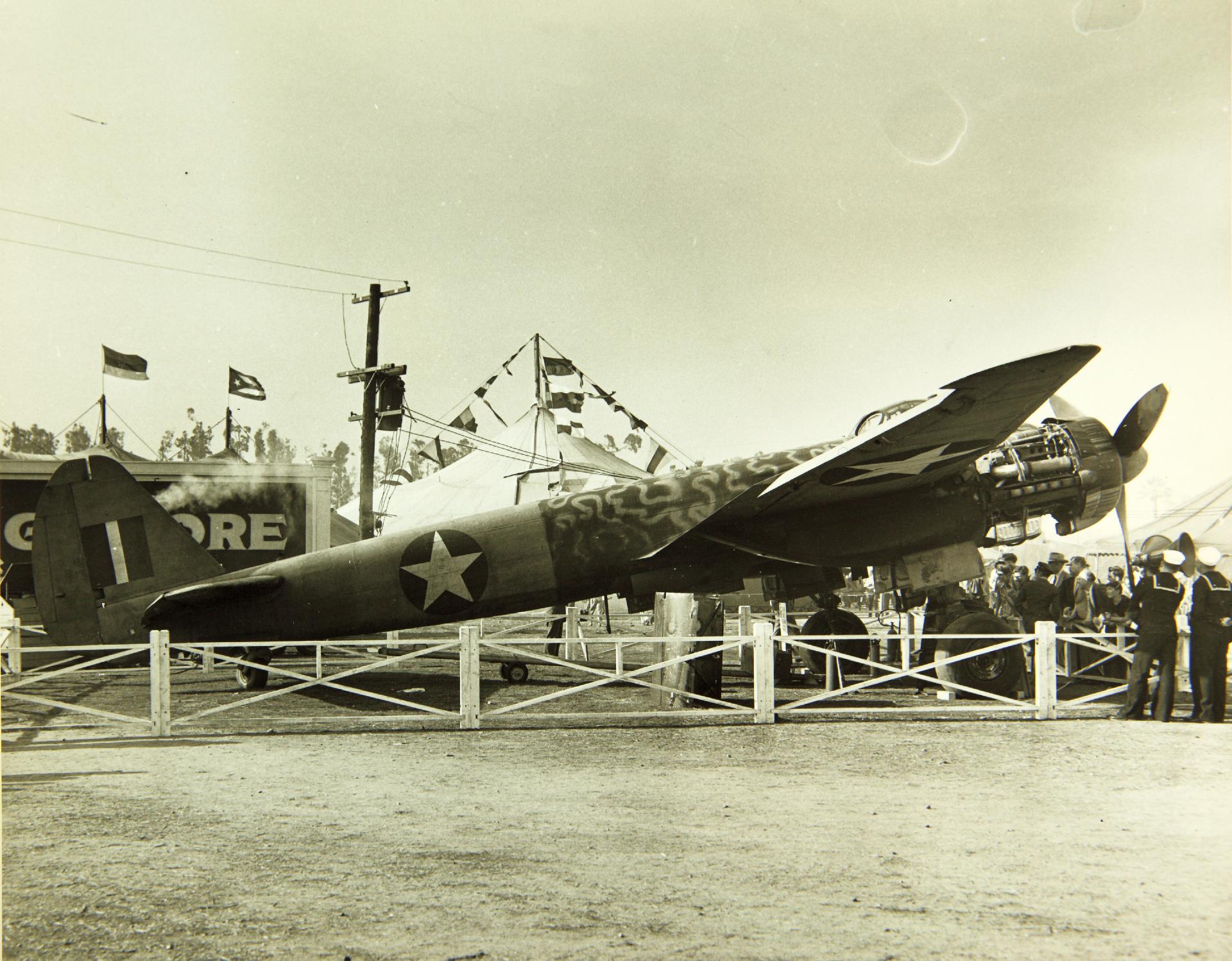

Once they were cleared, the commander of Morrison Field officially welcomed Warner Newby and George Cook back to the United States. Staff officers asked questions about the airplane and its performance. The arrival of the German bomber had attracted considerable interest from curious bystanders at the airport, and it was also reported that although the defense units at Morrison had been notified of the Junkers’ pending arrival, none of the civilian aircraft spotters had. At least three units had correctly identified the aircraft as a Junkers Ju 88. Once the crowds got a good look at the aircraft, the Ju 88 known as Baksheesh was secured for the night, as reports from the U.S. Weather Bureau warned of severe weather across the southeastern United States, but improved conditions were forecasted for the following day. On the morning of October 14, 1943, reports showed that the weather had yet to improve over the South. By 10:00 am, though, conditions had improved just enough for instrument flight rules (IFR) into Memphis and Dayton. With that, Newby and Cook suited up and took off, skirting the weather into Memphis to refuel there. From there, they headed out over Indiana to approach Dayton, Ohio, from the west, on the afternoon of October 14, Ju 88D-1/Trop. Serial Number 43-0650 finally arrived at Wright Field, completing a flight of five and a half days and covering around 12,000 miles.

With that, Warner Newby and George Cook had successfully delivered the Junkers bomber and returned home from their tour of duty in North Africa. Among those who greeted the two at Wright Field was Colonel “Olie” Hayward, Chief of the Air Technical Intelligence Center, but just as Major Newby was preparing to hand the airplane over to Colonel Hayward, Colonel Signa Gilkey, Deputy Chief of the Flight Test Engineering Division, arrived to take charge of the Ju 88. After some discussion, Newby and Cook transferred the Junkers to Col. Hayward, who immediately transferred it to Col. Gilkey so that the Flight Test Engineering Division could get to work on the aircraft. The following day, Maj. Newby and Lt. Cook would discuss the technical aspects of the flight in further detail with Col. Gilkey, and then with test pilot Captain Everett W. Leach, who would become the project officer for the Ju 88 at Wright Field and be the chief pilot responsible for flying it. After that, Lt. George Cook was released to become part of the USAAF’s Air Material Command, and a few days later, Major Warner Newby was made Chief of Bomber Flight Test Branch, Flight Test Engineering Division, Air Material Command, fulfilling his personal desire to become a B-25 test pilot, which he had held since he was initially trained to fly the aircraft in March 1942.

The arrival of Junkers Ju 88 D-1/Trop. Werknummer 430650 to the United States marked the first time that a twin-engine German bomber had been brought to the United States, and the airworthy condition of the aircraft meant that it would be flown for the duration of the war as a test aircraft for the United States Army Air Force, providing a valuable insight into the Ju 88’s flight handling. This also allowed for Air Intelligence units to create better identification documents, photographs, and films for American airmen and anti-aircraft gunners to distinguish Luftwaffe Ju 88s from Allied aircraft.

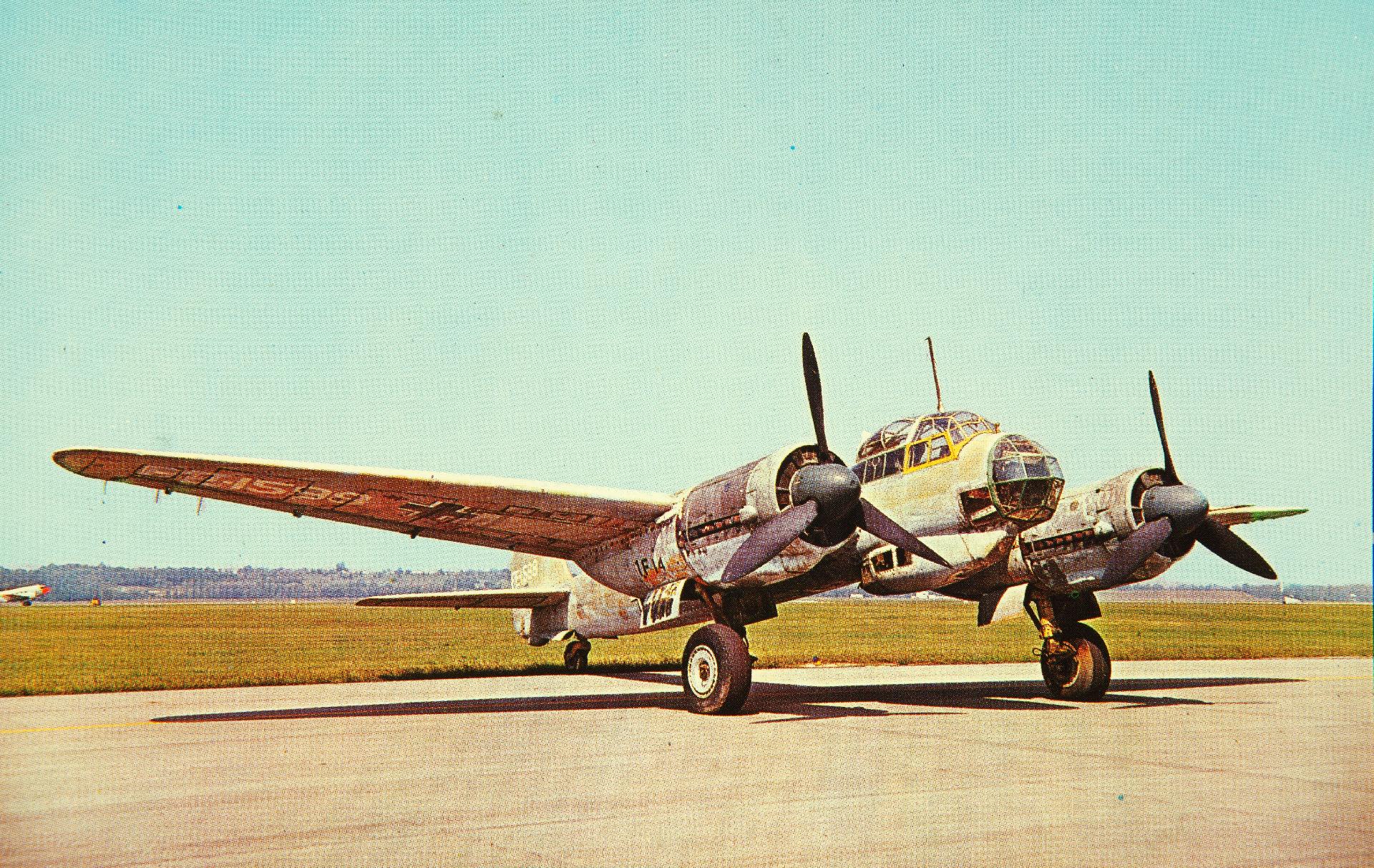

By March 15, 1944, the aircraft had logged 156 flying hours, with 36 of flight trials at Wright Field from November 9, 1943, to March 9, 1944, with the Evaluation Branch, Technical Data Laboratory, Technical Service Command. In addition to its trials at Wright Field, Baksheesh was further evaluated at Eglin Field, Florida, and went through some repaints during its service in America. Later in 1944, Baksheesh received the Foreign Equipment code FE-1598 (but was also identified as FE-105), and was repainted with German insignias for exhibition purposes, though these were not painted according to German measurements. During its time at Wright Field, FE-1598 was flown by test pilots Major Gustav Lindquist, Captains Everett Leach, W.A. Lien, Fred C. Bretcher and Ralph C. Hoewing.

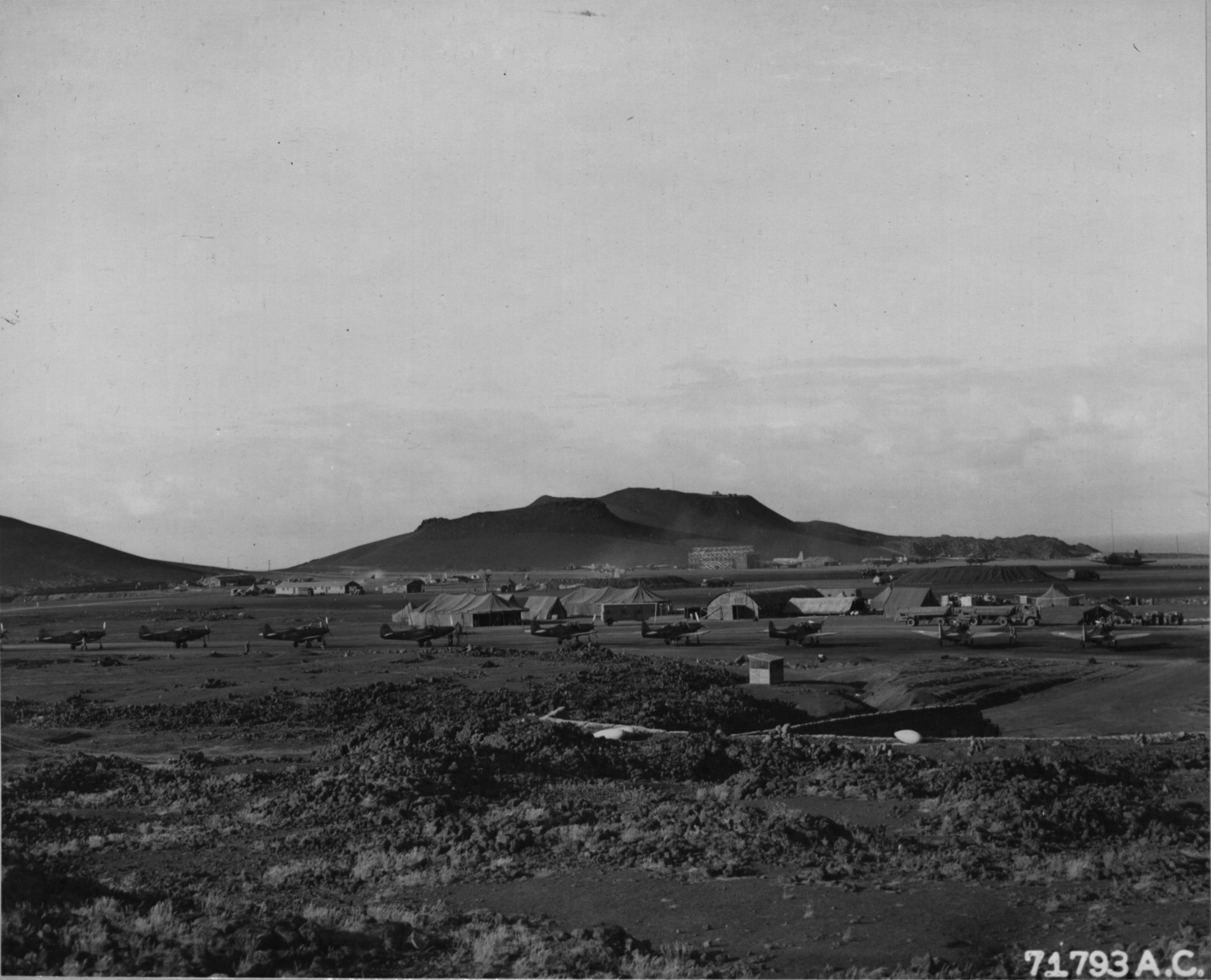

Soon after Baksheesh’s arrival at Wright Field, a second Ju 88 arrived for flight testing. This was Ju 88 A-4 bomber, Werknummer 4300277, which the 79th Fighter Group, Twelfth Air Force at Salsola Airstrip near Foggia, Italy, had captured. The 79th Fighter Group also captured several other German and Italian aircraft from the airfields around Foggia, from Focke Wulf Fw 190s to a Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero, and even managed to get them flying. Some of these aircraft were then ordered to be brought to the United States for further testing, and the outgoing commanding officer of the 86th Fighter Squadron, Major Frederic A. Bosordi, flew the Ju 88 A-4, nicknamed “The Comanche”, back to the USA, becoming the second Ju 88 to cross the Atlantic.

In the aftermath of VE-Day, the influx of captured German aircraft brought from Europe required the use of another facility, which led to the transfer of the Foreign Aircraft Evaluation Center to Freeman Army Airfield near Seymour, Indiana. In June 1945, Ju 88D-1 FE-1598 was one of these airplanes sent to Freeman. Additionally, another Ju 88, Ju 88 G-6 Werknummer 620116 was transferred from the RAF to the USAAF and brought to Freeman Field, while an example of a Junkers Ju 388, which featured a pressurized cockpit for high altitude bombing and reconnaissance, was also brought to Freeman Field.

With the war having ended, many aircraft now rendered surplus were to be scrapped and their aluminum melted down for peacetime applications. Of the Junkers Ju 88s brought to America, only Baksheesh remains today. As early as 1923, historic military aircraft were set aside for preservation and display at Wright Field. However, many of these aircraft were scrapped during WWII due to the lack of available storage facilities. With the influx of Allied and Axis aircraft in America, Army Air Force Chief of Staff General Henry “Hap” Arnold foresaw the need to preserve a select number of aircraft for preservation. As such, General Arnold called for more resources than had previously been spent to accomplish this objective. But until these museum facilities could be built, the aircraft set aside for preservation would have to be placed in storage and await their turn for public display.

While many of the WWII aircraft selected for preservation would be kept at a former Douglas C-54 plant at Orchard Place Airport (now Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport), Ju 88 FE-1598/Baksheesh would be sent to Davis-Monthan Army Airfield near Tucson, Arizona, and would sit in the desert sun in the place that would come to be known as the Boneyard. By the late 1950s, though, the United States Air Force Museum had been established on the Patterson Field side of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, and in 1960, finally returned to Dayton to be placed on display at the USAF Museum. The aircraft was displayed outdoors with the majority of the collection and was painted in German colors. By 1971, the museum itself had moved to its present-day location on the Wright Field side of WPAFB, and the Ju 88, now painted with the German fuselage code F6+AL, came to be displayed alongside many other aircraft on the outdoor ramp known today as the Air Park.

During the 1980s, though, the aircraft was towed to the museum’s restoration hangars and was repainted in Romanian colors by 1988 (albeit with the tail code “105” instead of “1”) and was displayed in the Wright Field Annex (now the museum’s storage hangars) until space was made in the WWII Gallery to accommodate the aircraft, where it remains on display to this day.

As for some of the participants in this story, Wing Commander Charles Sanford Wynne-Eyton, who instructed Warner Newby and George Cook in flying the Ju 88, was later killed on November 14, 1944, while flying a Liberator B Mk II, RAF s/n AL584 on a flight from Algiers to Paris with British and French VIPs. Warner E. Newby went on to serve for over 35 years in the U.S. Air Force before retiring at the rank of Major General. During his post-WWII service, he was involved in the development of both the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress and the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy, as well as commanding the Space and Missile Test Center at Vandenberg Air Force Base, California. He passed away in 2011 at the age of 92. Warner Newby also wrote two articles about his and Cook’s flight in the Ju 88, one for the January 1944 issue of Air Force, the USAAF’s official service journal, and in 1994 for The Torretta Flyer, the newsletter for the 484th Bomb Group Association. The latter article is incredibly well-detailed and highly recommended. A PDF of the article can be found HERE.

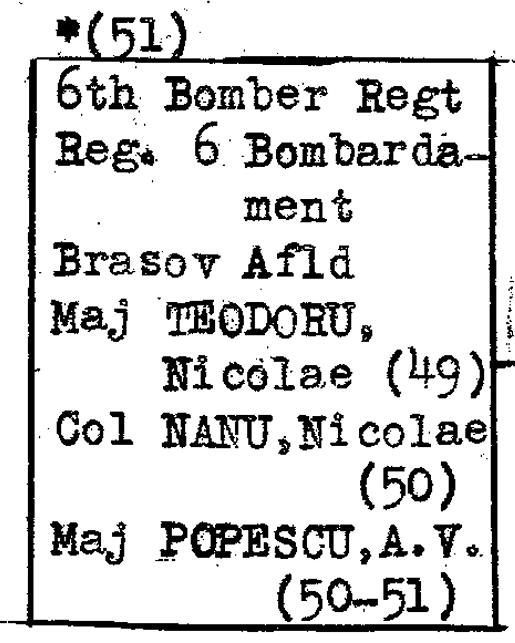

Little is known about Lt. George W. Cook, as many American servicemen had similar names during the war. Additionally, there is not much information about Nicolae Teodoru, the Romanian pilot who landed in Cyprus, either. According to a CIA document from April 29, 1953 assessing the strength of the Romanian Air Force’s bomber wings (which can be found HERE), a certain Nicolae Teodoru is listed as having commanded the 6th Bomber Regiment (Regimentul 6 Bombardament) at Brasov Airfield in 1949 before being replaced by two other commanders. The report says this of the personnel of the 6th Bomber Regiment: “Its personnel were gathered from the other air units, particularly the Transport Regiment, since its pilots had multiple-engine experience.” While it is not proof in itself that Teodoru returned to the Romanian Air Force reformed in the wake of the establishment of the country’s communist government, it is an interesting theory to go on.

Special thanks to Chuck Schmitz, the National Museum of the United States Air Force, and the National Archives of the United Kingdom for contributing reference material for the research for this article.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.