While many Americans believe that the continental United States has never been bombed by a foreign power, it simply isn’t true. The Japanese were quite intent on wreaking havoc on the West Coast and were quite inventive in their methods, however their efforts did not cause the damage hoped-for, and the US Government, for morale and strategic reasons kept it out of the news. The Japanese twice shelled the West Coast from submarines, sent over 9000 balloon bombs, delivered via the jet stream across the Pacific Ocean, and finally brought planes, launched from submarines to drop bombs on the continental US.

The Japanese balloon bomb program was an expensive failure, cataloged in quite some detail HERE. The shelling of the US West Coast amounted to two attacks from the relatively small gun mounted to the deck of a submarine, Japanese Imperial Navy Submarine I-17 shooting at a refinery in Elwood, California resulting in no loss of life or significant damage, though it did lead to mass hysteria that about an imminent West Coast invasion by Japanese forces and the “Battle of Los Angeles” on the night following the Elwood attack. The second shelling was performed by submarine I-25 against Fort Stevens in Oregon in June 1942, also resulting in little to no damage or casualties, and it was this very same sub that would launch the only aerial bombings of the US mainland during the war, on a later tour in September that same year.

I-25 was a B1-type submarine; fast, with a very long, over 14,000 mile range, and carrying a single collapsable seaplane stowed in a hangar on deck in front of the conning tower that could fly from the water or launched from a catapult built into the sub’s deck. Though classified as a scouting sub, the I-25 was a well-armed attack boat, equipped with 17 torpedoes and a substantial deck gun and sank many a target of opportunity during it’s missions. The crew compliment of I-25 was 97, including the aircraft pilot and crewman.

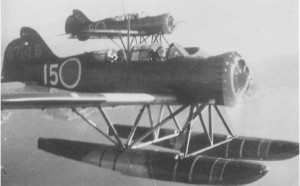

The Yokosuka E14Y (Allied reporting name Glen) was built for quick set-up and collapse in order to be stowed quickly as it’s mothership was particularly vulnerable while on the surface loading and unloading its plane. The E14Y and was built for range, not for speed, able to stay aloft for 5 hours with a normal cruising speed of 85MPH and a range of approximately 400 miles. For defense the plane had a single rear-mounted machine 7.7mm machine gun.

The idea of utilizing submarine-deployed bombers had originated with Warrant Officer Nubuo Fujita, a respected test pilot who formally submitted this idea to the navy in 1941 proposing that floatplanes dispatched from Japanese submarines could attack the Panama Canal and US West Coast’s naval bases and aircraft manufacturing infrastructure in addition to the toll the subs were taking on shipping.

It would be Fujita’s success overflying enemy targets with his Yokosuka E14Y seaplane that served as proof of concept for his proposal. On previous missions aboard I-25, Fujita overflew and and gathered intelligence at Sydney Harbor, Melbourne and Hobart in Australia as well as Auckland, New Zealand and Fiji. On the next mission Fujita overflew US military installations on Kodiak Island to provide intelligence for a proposed Japanese Aleutian Islands Invasion. Having accomplished all of these successful observation flights, and having been the individual who suggested it in the first place, Fujita was selected by Japanese military brass for a bombing mission against the mainland United States.

As the Japanese did not have the wherewithal to launch full-sclae aerial attacks against the population centers of the increasingly-fortified US West Coast a decision was made to bomb the dense forests of the Pacific Northwest, hoping to start uncontrollable wildfires. The diversion of resources to battle the flames, destruction of property of the fires got large enough and the psychological hit the American public would take if the mission was successful were certainly worth risking six bombs, one plane and two men.

Just before dawn on September 9, 1942, Fujita and his crewman, Petty Officer Shoji Okuda, seated themselves in the floatplane, which had been assembled on deck. Mounted to the plane were two 170 pound thermite bombs, designed to breakup upon impact, spreading 2,700 degree fire over a hundred yard diameter area. Fujita dropped two bombs, one on Wheeler Ridge on Mount Emily in Oregon, and the second, which Fujita estimated to have been dropped five or six miles east of the first. The Wheeler Ridge bomb started a small fire which US Forest Service employees were able to extinguish. Rain the night before had made the forest very damp, the fires failed to spread. During the flight the plane was spotted by a number of people, and it’s distinctive sound (described as sounding like a Ford Model T engine with a broken rod) was heard by even more as he flew over Brookings, Oregon. The multiple reports of the aircraft resulted mobilization by US forces to find and destroy the invader. While Fuji and Okuda managed to get back to I-25 and get the plane stowed, a USAAF A-29 Hudson spotted the sub and attacked, followed rapidly by Coast Guard cutter and three more aircraft. The rapidly responding US forces forced I-25 to submerge and hide on the ocean floor off Port Orford. While the attack had caused only minor damage to the sub, the quick mobilization of defensive forces made the Japanese more cautious for their second attack.

Three weeks later, I-25 dispatched the Glen for another bombing run, and this time it would be a night raid. The plane was launched 50 miles out to sea, and as the entire Oregon Coast was under blackout, used the only navigational beacon that remained, the Cape Blanco lighthouse to guide them in to the coast and the waiting forests. Fujita flew east past the lighthouse for half an hour before dropping his two bombs. Fujita confirmed that he saw the bombs explode, though forest workers who heard the distinctive sound of the planes Hitachi Tempu 12 nine-cylinder air-cooled radial engine, as a result of the noise, rangers scoured the forest but found no evidence of the bombs or fires.

The planned third bombing run never occurred due to bad weather and heavy seas and the captain of I-25, Captain Tagami decided to concentrate their efforts on disrupting shipping. On October 4, 1942, I-25 went on to mortally wound the the 6600-ton tanker Camden which was carrying 76,000 barrels of gasoline and went to ground and later exploded 6 days after I-25 had torpedoed her, and on October 5th, sank another tanker, the Larry Doheny with its cargo of 66,000 barrels of oil. On October 11th with supplies running low, I-25 was heading back to Japan when she spotted what they believed to be two American submarines. Firing her last torpedo, she sunk what would later be disclosed to be Soviet Submarine L-16.

(Image Credit: Smithsonian Air and Space Museum)

Upon I-25’s docking at Yokosuka, Fujita came home to discover, to his surprise, that he had been made into a national hero. The government needed a propaganda victory in the wake of the troubling Doolittle Raid. The practical impact of the bombing of the Oregon forests was virtually nil, but it did show the Japanese that the concept of launching offensive aerial bombardment was sound. The Japanese Navy began construction of the Sen Toku I-400-class of submarines early in 1943. The I-400s were the largest submarines of World War II and remained the largest ever built until the construction of nuclear ballistic missile submarines in the 1960s. They were submarine aircraft carriers, designed to surface, launch their planes, then quickly dive again before they were discovered and able to carry three specially-designed Aichi M6A Seiran aircraft underwater to their launch points anywhere on the globe. Though originally planned to be a fleet of 18 subs, only three were completed.

Warrant Flying Officer Fujita continued reconnaissance flying until 1944, when he returned to Japan to train kamikaze pilots. His crewman, Petty Officer Okuda, was later killed in the South Pacific. I-25 was sunk less than a year later by USS Patterson (DD-392) off the New Hebrides Islands on September 3, 1943.

Fujita was invited to Brookings, Oregon in 1962, after the Japanese government was assured he would not be tried as a war criminal. He gave the City of Brookings his family’s 400-year-old samurai sword as a gesture of friendship. For the most part the town treated him with respect and affection during the visit, although his visit still raised some controversy. Fujita returned to Brookings in 1990, 1992, and 1995. In 1992, he planted a tree at the bomb site as a gesture of peace.

He was made an honorary citizen of Brookings several days before his death at the age of 85 in 1997, and in October 1998, his daughter buried some of his ashes at the bomb site.

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.