Combat survival stories are numerous and often harrowing. But the award for Luckiest Hero Alive must belong to Sgt. Alan E. Magee. In fact, Smithsonian Magazine named Magee one of the 10 most amazing survival stories of World War II. As is the case with many of his age, Magee signed up for the Army Air Corps immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor. His short 5’7” stature and 150 lbs. build, he was assigned as a belly turret gunner on a B-17F flown by Capt. Jacob W. “Jake” Fredericks. Fredericks had worked as an engineer for the Kellogg’s Cereal Company in Battle Creek, Michigan, prior to the war, thus naming his aircraft, appropriately, the Snap! Crackle! Pop!, the advertising jingle for one of the company’s cereal products, Rice Krispies. The space inside the turret was small and cramped, and Magee was able to finagle his way inside, even if it was without his parachute attached to his body. Instead, it was attached to a hook above his turret.

The Mission

On January 3, 1943, Magee was assigned to his seventh bombing mission. He was 24 and was one of a ten-man crew. They took off from Molesworth, Cambridgeshire, UK, for their target, a German submarine port in “Flak City,” St. Nazaire, France. There were 85 B-17s involved in the raid, along with some fighter planes to escort them. When Magee’s bomber reached its target, it came under heavy fire from German anti-aircraft guns and fighters. The bomber took a couple of nasty blows on its wing and engine, starting a fire; it started spiraling towards the ground, spinning at a high rate of speed. Magee’s parachute was shredded in the gunfire, and since he saw he was fresh out of options and saw a small opening in the fuselage, he quickly jumped, sans his parachute. He was unaware, however, that he had jumped 4 miles (More than 20,000 feet) above the ground.

Magee was one of three members of the crew to survive. The aircraft crashed into another aircraft over St. Nazaire. All of the remaining crewmembers were killed in the crash. Once the aircraft crashed, the Germans cut the panel that carried the aircraft’s name and exhibited it in the German headquarters. Later, when the city was liberated, the Germans tossed the scrap into a ravine where it was rescued by some French citizens. It still exists, hanging in an unknown location in the city. Magee plunged almost 22,000 feet, falling unconscious before crashing into the roof of the St Nazaire railway station. When he regained consciousness, as the Germans were taking him to a hospital, he exclaimed, “Thank God I am alive.” Magee once told a friend that the Germans had great respect for those who survived miraculously. The extent of his wounds and injuries was never revealed.

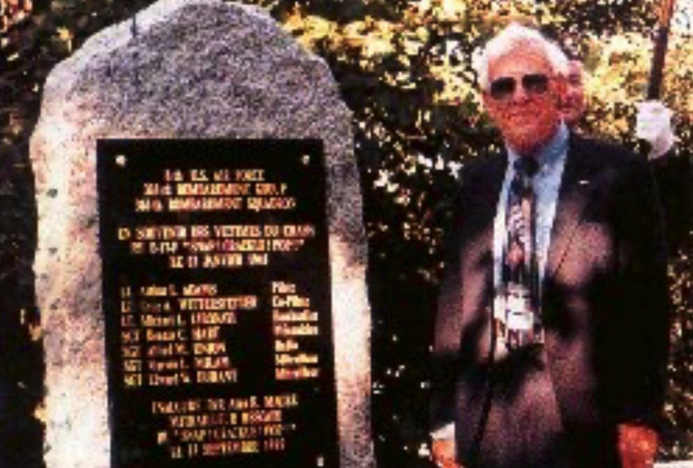

On the 23rd of September 1993 (some accounts say 1995), Alan E. Magee, accompanied by his wife Helen, returned to St Nazaire to take part in a ceremony sponsored by French citizens, dedicating a memorial to his seven fellow crewmen killed in the crash of Snap! Crackle! Pop! in the forest at La Baule Escoublac on Jan. 3, 1943. The mission Magee was a part of turned out to be a failure for the Allied forces. The US Army lost 75 airmen, along with seven planes, while fourtyseven planes were badly damaged, the Free Republic reports. Magee survived, keeping all his limbs, and staying in various German camps as a Prisoner of War, most notably Stalag 17B in Braunau, Gneikendorf. The camp was liberated in May 1945. Alan Magee received the Air Medal for meritorious service and the Purple Heart for his achievements in the war. After the war, Magee and other members of the crew were honored with the placement of a stone memorial in the town.

Home at Last!

After the war was over, Magee worked for the airline industry until 1979, when he retired and moved with his wife to New Mexico, where he lived a quiet life, according to a friend interviewed by a reporter. At some point, he moved with his wife to San Angelo, Texas, where he died in a local hospital on December 20, 2003. He was buried in Pioneer Memorial Park in Grape Creek, Texas. His survivors were his wife and a sister in Houston. He was quoted on his return to France at the railroad station where he laded on his famous fall, commenting, “I thought it was much smaller.”

Amazing.

Very similar to the British Lancaster gunner Flight Sergeant Nicholas Alkemade, who also survived a jump from his bomber with no parachute and was then taken prisoner. Two very lucky men. I wonder if they ever met?

Mr. Low,

Thank you for your kind note. Gee. Lucky is an understatement.

The truth is I don’t know if they knew each other or not, but they could certainly start an exclusive club..

Thank you for your note.

Mike Michelsen