Nestled in the Santa Clara River Valley, on the banks of the Santa Clara River, sits Santa Paula Airport. For nearly one hundred years, the airport has been located in the community of Santa Paula, known for its citrus groves and oil fields. It is rich in aviation history and is today one of the last havens for the vintage aviation community in Southern California. Its old tin hangars truly make you feel as though you have taken a step back in time. Suppose you happen to travel to Santa Paula on California State Route 126, either east from Santa Clarita or west from Ventura on the first Sunday of the month, though. In that case, the airport opens its doors to the public, and part of that involves the Aviation Museum of Santa Paula. Compared to many other aviation museums, it is a very humble one, but what it lacks in sheer quantity of airplanes, the Aviation Museum of Santa Paula more than makes up for this in displaying the richness of Santa Paula’s aviation history and in some truly vintage aircraft.

Santa Paula Airport traces its lineage back to 1927, when local rancher Ralph Dickenson, whose first foray in aviation in 1910 involved the construction of a homemade glider, built an airstrip on his ranch. Inspired by Charles Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic, Dickenson went down to Long Beach, California, and soloed after just eight hours of instruction. Immediately after this, he purchased an International F-17 Sportsman, a three-seat open cockpit biplane with a Curtiss OX-5 90 hp V8 engine built by the International Aircraft Corporation in Long Beach and took it back to his ranch in Santa Paula. Soon after returning home, his local flights attracted considerable interest, and he began selling rides for $2.50 per passenger (worth $44.58 in 2025).

1928 would be one of the worst years in the history of the Santa Clara River Valley. Just before midnight on March 12, 1928, the St. Francis Dam, which had opened just two years prior to provide a reservoir for the growing city of Los Angeles and hydroelectric power to the communities of the Santa Clara River Valley, collapsed, with a great flood sweeping away entire farms from Santa Clarita to the Pacific coast at Ventura. At least 431 people drowned in the disaster, and though Dickenson survived the flood, his hangar and airplane had been washed out. He later found the hangar half a mile downstream, with the International Sportsman still inside with only minor damage.

It was at this point that Dickenson and another rancher, turned pilot, Dan Emmett, decided that Santa Paula should have its own dedicated airfield. Despite the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, Dickenson had convinced 19 other farmers and businessmen to donate $1,000 each for the construction of Santa Paula Airport along the Santa Clara River at the south end of town. Many of these farmers also brought their equipment with them to level the site for the airport. On the weekend of August 9 and 10, 1930, Santa Paula Airport was officially dedicated. The dedication ceremonies saw local pilot Edith Bond and Hollywood stunt pilot Garland Lincoln perform aerobatics in their airplanes over the field, while aviation celebrities of the day, such as Florence “Pancho” Barnes and Roscoe Turner, accompanied by his pet lion cub Gilmore, and a Goodyear blimp were present at the show as well.

Throughout the 1930s, Santa Paula Airport remained in operation, with local aviation enthusiasts watching planes taking off and landing, and young pilots earning their wings in the skies above the valley, where the California condors soared. That all changed on December 7, 1941, when word reached the continental United States that Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor. Fearing Japanese air raids, the military ordered all private aircraft on the West Coast grounded or to be requisitioned for use as official spotter planes to search for hostile warships off the coast. Civilian aircraft were restricted from flying up to 150 miles from the Pacific coast. While many municipal airports in California were used as auxiliary training fields, Santa Paula Airport was simply closed until 1945, with padlocks being placed on the hangar doors. With the end of WWII, operations at Santa Paula Airport resumed, and while many prewar fields in Los Angeles and Orange Counties were sold off to real estate developers, Santa Paula’s agricultural industry ensured that the airport would flourish. Indeed, the old tin hangars attracted a growing number of pilots who took an interest in finding, restoring, and flying antique airplanes dating back to the 1920s and 1930s, alongside those who flew a wide array of contemporary general aviation aircraft from companies such as Aeronca, Beech, Cessna, Luscombe, Piper, Stinson, Taylorcraft, and others. Today, Santa Paula Airport is the last non-towered airport in Ventura County, and with aviation enthusiasts wanting to see the vintage aircraft, some of the local pilots and airport managers came together to establish the Aviation Museum of Santa Paula.

The museum consists of two hangars across from each other. One displays the museum’s de Havilland DH.60M Gipsy Moth G-AAMZ/N60MZ. The aircraft has a winding story of how it got to Santa Paula. It was originally built in England in 1929 as construction number 1076, where it was bought by Spanish citizen Carlos de Salamanca. By 1930, it was being flown by the Real Aero Club de Andalucia (Royal Aero Club of Andalucia) as M-CHAA and later EC-HAA. According to Air Britain’s DH.60 Moth Production List, the aircraft was impressed into military by Nationalist forces shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936. That month, it is reported that the aircraft was shot down by ground fire at La Roda, Cordoba, and that its two pilots, Recasens Serrano & Tomas Muruve, were captured and later executed by militia members loyal to the Spanish Republic. The aircraft itself was later retrieved and, following the Nationalist victory in 1939, was returned to the Real Aero Club de Andalucia and, in 1941, was re-registered as EC-HAU. In 1947, the aircraft was registered as EC-ABX and flown by the Real Aero Club de Sevilla before being passed to a number of private owners in Spain and eventually winding up in storage in Sabadell, Catalonia.

In 1987, the aircraft was sold to English pilot and DH.60 Moth restorer Clifford Charles “Cliff” Lovell. It has also been reported that Lovell rebuilt c/n 1076 with parts from another Spanish Moth, c/n 1293/EC-AAN, which had also been in the inventory of the Real Aero Club de Andalucia and had also been impressed into service with the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War. Whatever the case, the former EC-HAU emerged from Lovell’s workshop as G-AAMZ and was flown by him in July 1994. Over the next four years, DH.60 G-AAMZ at several flying events in England until 1998, when it was sold to David Watson, a former Lockheed engineer who kept a hangar at Santa Paula Airport. Watson was also a fan of the de Havilland DH.60 Moth, and he came to own three airworthy Moths at Santa Paula (N1510V, N60MZ, and N916M). Watson had G-AAMZ registered with the FAA as N60MZ, but kept the paint scheme applied by Lovell, including the prominent British registration, intact. After Watson’s death in 2021, DH.60 Moth N60MZ was donated to the Aviation Museum of Santa Paula, where it can be seen alongside the unmarked fuselage frame of another de Havilland DH.60 Moth.

In addition to the DH.60 Moth, the Aviation Museum of Santa Paula also features an airworthy replica of a Mignet HM.293 Pou-du-Ciel (Flying Flea/Louse). Designed by Frenchman Henri Mignet as an affordable, easy-to-fly airplane that could be an alternative to automobiles for personal transport, the original Pou-du-Ciel, the HM.14, had a promising start in 1933 that was cut short by a series of fatal crashes on account of a design flaw. Though Mignet corrected his design, the Pou-du-Ciel never fully emerged from the negative publicity around it but still managed to carve out a respectable niche with successive variants built to a variety of specifications. The aircraft found in Santa Paula was built over a ten-year period from 1973 to 1983 by Frank E. Perry, a pilot and homebuilt kit airplane builder from Camarillo, California. The aircraft was given the registration N293FP, and the badge on its instrument panel states its construction number to be FP100. The badge also states that it is powered by a Hercules engine, which in this case is a four-cylinder horizontally opposed inline engine for a military generator similar in appearance and function to a Continental inline engine. The aircraft’s wings and horizontal stabilizer also fold to be stored in smaller hangars if needed.

Sadly, Perry was killed in 1994 while flying a homebuilt replica of a 1924 Dormoy Bathtub out of Camarillo Airport. Still, the HM.293 Pou-du-Ciel he built is now on permanent display at the Aviation Museum of Santa Paula. Its compact size and folding wings have enabled it to be towed on trailers or parade floats for local events in Santa Paula, such as the Labor Day Parade, where it received the trophy for Best Designed Entry.

Across the tarmac, the museum maintains another hangar, which includes a replica of Otto Lilienthal’s glider from the 1890s suspended above an Erco Ercoupe, N99853. On the opposite end of the hangar from the Lilienthal glider is a biplane hang glider wearing markings inspired by the all-red scheme of the Red Baron’s fighter aircraft of WWI, complete with red paint and Iron Crosses. Besides the airplanes of the Aviation Museum of Santa Paula, the museum is also rich in the history of the Santa Paula Airport. There is the horizontal stabilizer of an International OX-5, similar to the one flown by Ralph Dickenson back in the 1920s, while the exhaust collector ring from the Wright J-6-7 Whirlwind engine on Dickenson’s Stinson Detroiter is also on display next to the International’s stabilizer.

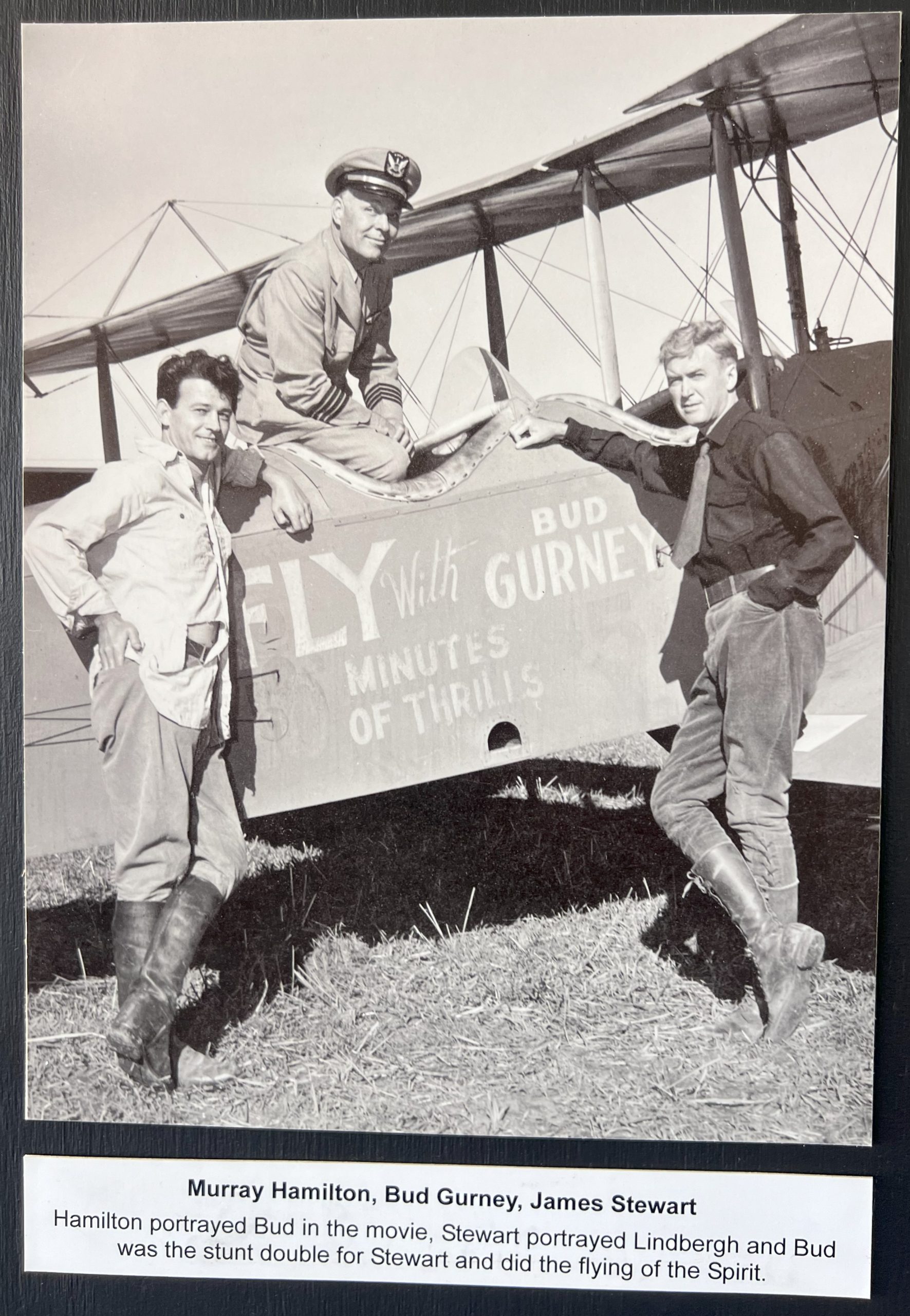

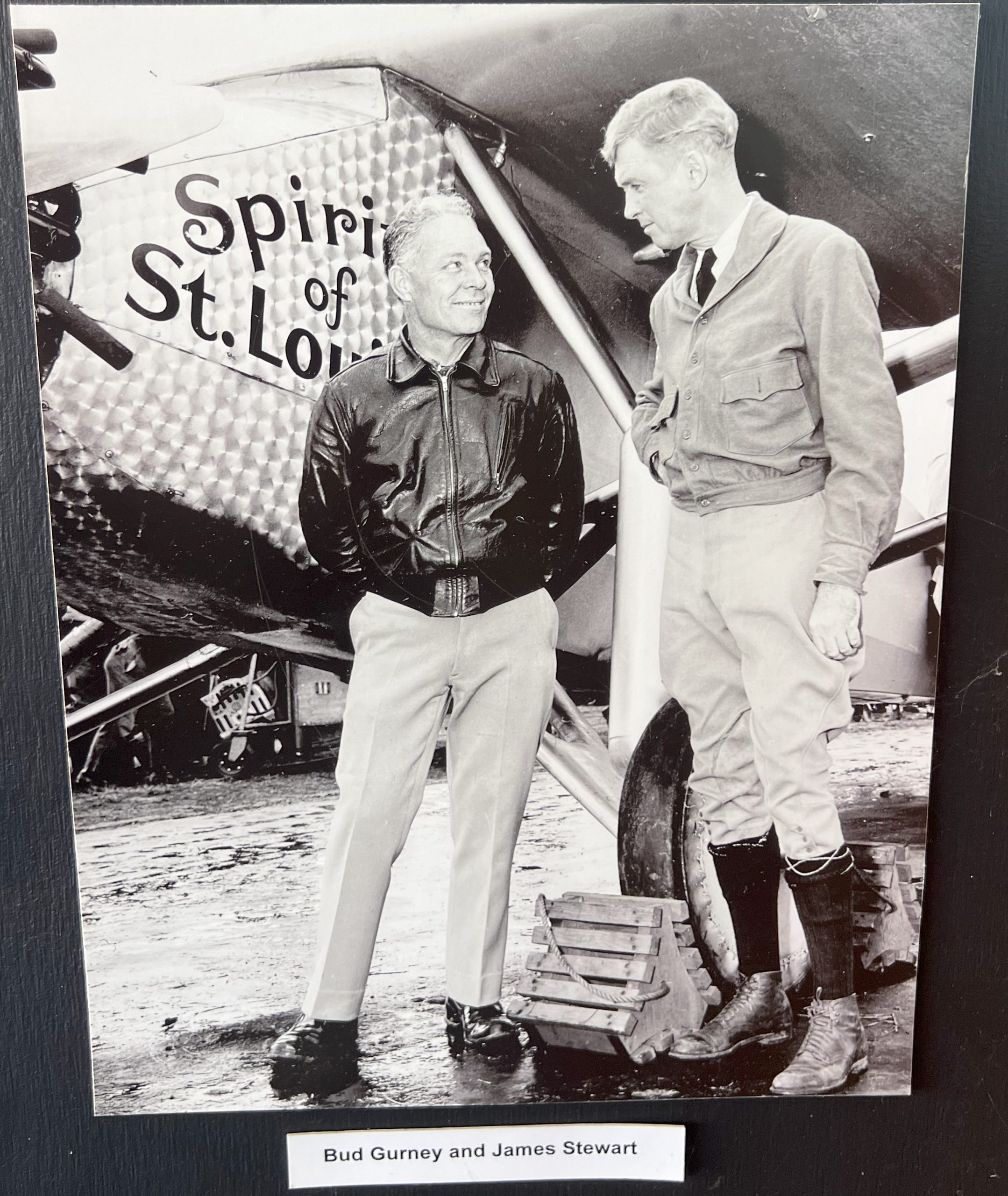

Many notable aviators kept their planes in Santa Paula’s hangars after WWII. There was Harlan “Bud” Gurney, who had learned to fly in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1922 alongside a young, tall man from Minnesota named Charles Lindbergh. Bud and “Slim” (Lindbergh’s nickname) remained lifelong friends, having flown together as barnstormers and air mail pilots across the Midwest during the 1920s, and while Lindbergh became an icon after flying nonstop and solo from New York to Paris, Gurney eventually became a pilot for United Airlines, flying for the company from 1932 to 1965. Bud Gurney and his wife, Hilda, frequently flew out of Santa Paula Airport, especially in his retirement years, where he restored and flew vintage aircraft. In 1957, Gurney was hired as a technical consultant for the film The Spirit of St. Louis, in which Jimmy Stewart played the role of Lindbergh, and Gurney was portrayed by actor Murray Hamilton. In 1969, Bud Gurney and Charles Lindbergh made one final flight together in Gurney’s de Havilland DH.60 Gipsy Moth N1510V out of Santa Paula Airport (in fact, this very aircraft is still maintained in airworthy condition at Santa Paula Airport and was formerly flown by the late David Watson). The museum at Santa Paula displays photos of Gurney and Lindbergh together with the airplane.

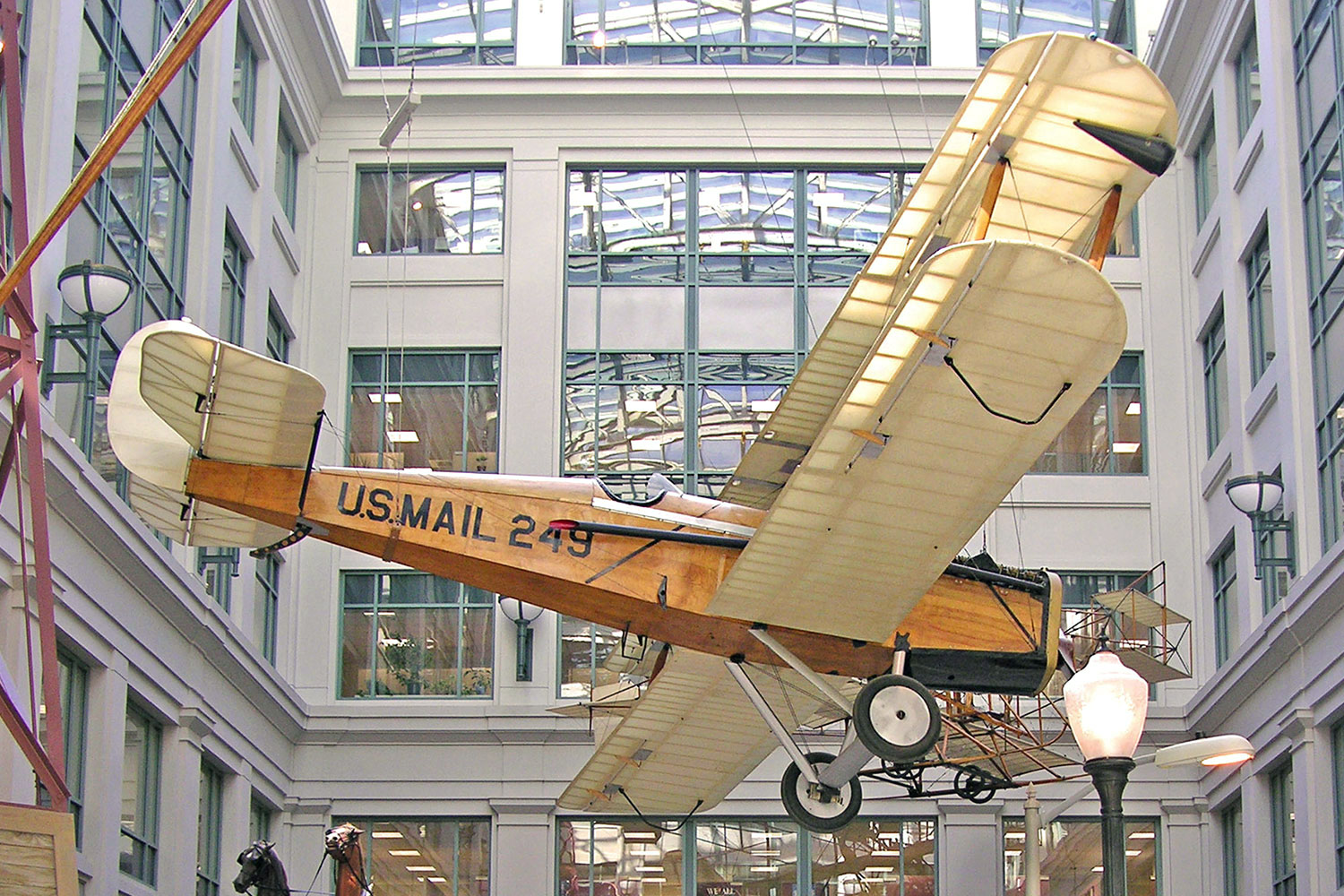

Another aviator of the 1920s who called Santa Maria home was John W. “Bill” Hackbarth, who had soloed in a Standard J-1 trainer in 1921, Rock Springs, Wyoming, after just one ride in an airplane as a passenger. In addition to becoming a barnstormer and flying around the country, Hackbarth had been a mechanic for the U.S. Postal Service’s airmail service. In the 1930s, Hackbarth set up shop in Santa Paula as a flight instructor and mechanic. In 1965, Hackbarth and other airmail pilots and mechanics sought to find a way to commemorate the upcoming 50th anniversary of the first scheduled U.S. Air Mail service flight on May 15, 1918. One of the old timers, Henry G. Boonstra, had recalled how on December 15, 1922, he had crashed a de Havilland DH-4 mailplane (U.S. Mail number 249) in a snowstorm on Porcupine Ridge near Coalville, Utah, while on a flight from Salt Lake City bound for Rock Springs, Wyoming. Boonstra had to trek through waist-deep snow for 36 hours before reaching a nearby ranch where he was later picked up and returned to flight duty. As it happened, Boonstra’s DH-4 was still on the top of Porcupine Ridge, sitting above the tree line at 9,400 feet. Though its mail and Liberty L-12 engine had both been salvaged back in 1922, Hackbarth was able to travel to the ridge, and with the help of a local sheep rancher, he salvaged “600 pounds of junk” to bring back to Santa Paula.

Over the next two years, Hackbarth and a team of restorers worked on the reconstruction of Old 249, as the aircraft came to be known, both at Santa Paula Airport and at Hackbarth’s ranch nearby. But on October 15, 1967, a devastating brush fire destroyed the workshop on Hackbarth’s ranch. Old 249’s fuselage and three wings went up in smoke, just when Hackbarth had hoped to begin test flights the following month. Just four days later, though, the airmail veterans redoubled their efforts, finding a new Liberty engine stored in a Pennsylvania barn and building a new fuselage and wings for the aircraft. In April 1968, Bill Hackbarth took Old 249 on its first port-restoration flight. The following month, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the first official U.S. Airmail flight in 1918, Hackbarth flew the DH-4, registered with the FAA as N249B, on a cross-country flight from San Francisco to Washington, D.C., where Hackbarth, Boonstra, and the old airmail fliers donated the aircraft to the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. After being loaned to the San Diego Air and Space Museum during the 1980s, DH-4 Old 249, which was rebuilt and test flown at Santa Paula Airport, is now displayed at the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C.

Another pilot who frequented Santa Paula Airport was Miraslav “Mira” Slovak. Born in 1929 in the village of Cífer, Slovakia, Slovak was just nine years old when Nazi Germany began its occupation of Czechoslovakia. During the war, Slovak witnessed dogfights between Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers and German fighters before living through the Soviet advance through Czechoslovakia. Though the Germans were defeated and Slovak had enlisted in the Czechoslovakian Air Force at just 17, the country went through a communist coup d’état in February 1948 and became a satellite of the Soviet Union. Slovak sought freedom but knew he had to bide his time. In 1953, while flying as a pilot for Czechoslovakian Airlines, Slovak hijacked a Douglas DC-3 he was flying on a flight from Prague to Brno and diverted to Frankfurt, West Germany, where he requested asylum in the United States. Upon being granted asylum and being debriefed by U.S. intelligence, Slovak began his American aviation career, first as a crop duster in Washington state before being hired by Bill Boeing, Jr. as his personal pilot and becoming a hydroplane racer, gaining fame by racing the speedboat, Miss Wahoo. Slovak also earned further acclaim as an air racer by winning Gold in the Unlimited Class race of the first Reno Air Races in 1964, flying to victory in the Grumman F8F Bearcat “Miss Smirnoff”. Slovak saw flying as the ultimate expression of freedom, saying that “In America, freedom is like air”. When he was not performing aerobatics in airshows across the United States or flying for Continental Airlines, Slovak flew his Bücker Bü 131 Jungmann out of Santa Paula Airport and was a resident of the airport until his passing in 2014. His Jungmann is now flown out of Wisconsin and has been seen camped in the Vintage section at the EAA Airventure show in Oshkosh.

Many Hollywood figures also found refuge at Santa Paula Airport. Actor Steve McQueen maintained a hangar for his Stearman biplane and his collection of motorcycles, describing the airport as “my sort of country club”. Walter “Matt” Jeffries had served as a B-17 pilot with the 301st Bombardment Group during WWII before becoming a set designer for Hollywood, where he gained fame for being the original designer of the Starship Enterprise, along with the ship’s bridge and sick bay, as well as the emblem for the Klingons and other ships depicted in the original series. At Santa Paula, Jeffries maintained and flew a 1935 WACO YOC NC17740, c/n 4279 (now registered with the FAA to a private owner in North Carolina). When Leonard Nimoy was not playing the half-Vulcan, half-human character of Spock on the bridge of the starship Enterprise, he could also be found flying his Piper Cherokee Arrow into Santa Paula Airport with his family.

The Aviation Museum of Santa Paula also works with other organizations at the airport, such as the Santa Paula Aviation Career Explorers (SP-ACE) program, which offers unique opportunities for local youth interested in aerospace to learn through exposure to airplanes, pilots, and airport facilities in order to pursue an array of professions within the aviation industry, such as pilots, aircraft mechanics and air traffic controllers. The SP-ACE program also fosters networking opportunities for these students to meet professionals who can help guide their career choices. Additionally, when the museum is open, free tram tours of the airport are provided, which allow guests to see other vintage aircraft in privately-owned hangars, with many of the owners opening their hangar doors wide to allow the public to have a look at their airplanes, or even wave back to the tram guests and drivers.

While the museum is a small facility, it is truly one of the last havens for vintage airplanes in southern California, and the airport remains active in helping the community, from being used by crop duster pilots to fly aerial spraying missions over the rolling citrus groves to providing a base of operations for fighting local wildfires. Once again, the Aviation Museum of Santa Paula is open from 10 am to 2 pm on the first Sunday of every month, with a suggested donation of $10 being encouraged. You can also support the museum by purchasing merchandise and used books from the gift shop. To learn more about the Aviation Museum of Santa Paula, visit the museum’s website HERE.

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.