By Stephen Chapis

When Lockheed Skunk Works unveiled the XF-104 in 1954, it possessed out of this world looks and performance. In 1958, just months after the F-104A entered service with Air Defense Command (ADC) Lockheed and the Pentagon decided to prove the latter by making a series a series of world record flights. In this article, the first of two-parts, we will hear first-hand accounts from three pilots that flew their Starfighters into the deadly upper reaches of the stratosphere.

MAY 7, 1958- WORLD ALTITUDE RECORD

The first world record attempt by the F-104 was the World Altitude Record. This record would require the pilot to fly at maximum speed at a specific altitude and pull up into a steep zoom climb, thus converting kinetic energy into potential energy. The selected aircraft, JF-104A 55-2957, received a number of modifications for the altitude flights, including the installation of a General Electric YJ79-GE-7 engine was installed which required extra cooling doors for increased ground cooling. Lockheed Aircraft Corporation Engineering Test Pilots J.F. Holliman and William C. Park flew ‘957 on nine occasions between April 21 and April 30, 1958 to develop the optimum technique for obtaining maximum altitude, based in part on information from an IBM 704 Digital Computer.

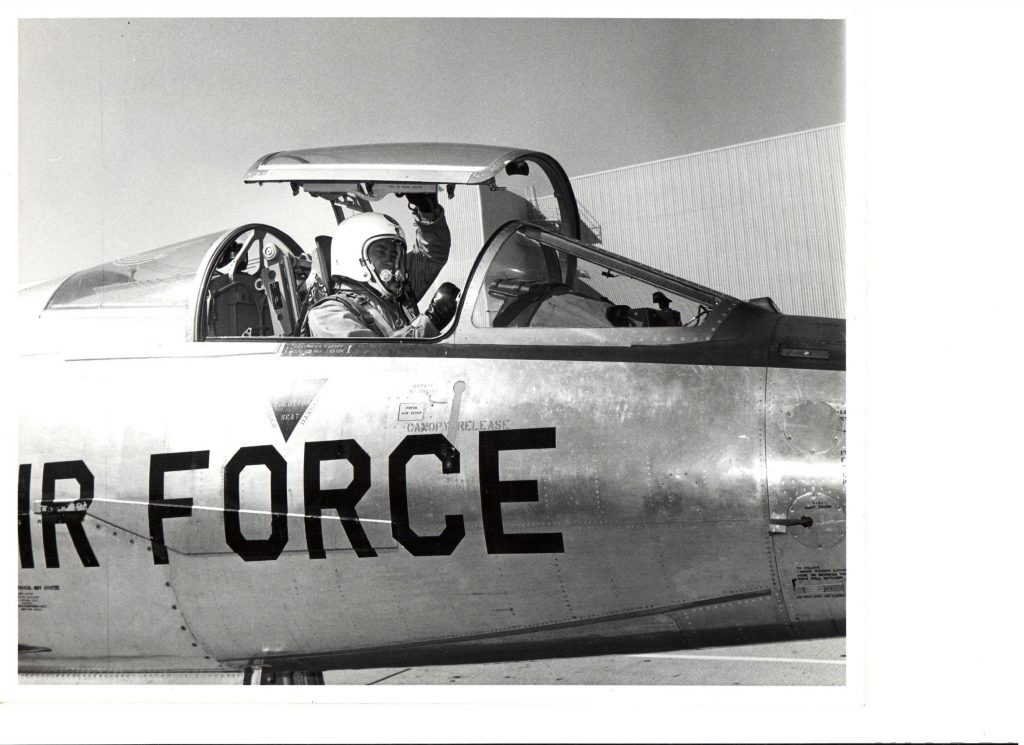

On April 30 Major (Maj) Howard ‘Scrappy’ Johnson made his first of six indoctrination flights. Scrappy had been flying North American F-86D Sabre Dogs at Castle AFB, California when he heard that the 83rd Fighter Interceptor Squadron (FIS) would be receiving F-104s and managed a transfer to that unit. In his autobiography Scrappy, Maj Johnson gives a vivid account of the first world record set by the F-104. On the morning of May 7, 1958, Scrappy was ready for an official record attempt, his total F-104 time stood at just 30 hours.

A number of Lockheed executives and other dignitaries watched as Scrappy launched out of Palmdale and climbed to 35,000 feet while heading west towards Santa Barbara. He lit the afterburner, made a wide 180-degree climbing left turn, pointed the needled nosed Starfighter towards Edwards AFB and accelerated to 2.23 Mach. When Scrappy announced his arrival over Edwards with a thundering sonic boom he’d climbed to 45,000 feet. Upon reaching a pre-designated spot in the sky, he executing a gentle 2.7G pull into a 52-degree climb. The F-104 rocketed towards the heavens. To ensure he established the correct climb angle engineers drew a line on the canopy for Scrappy to align with the horizon. When he shot through 63,000 feet at 1.25 Mach the afterburner blew out followed seconds later by a total flame out at 67,000 feet. Scrappy’s MC-4 partial-pressure suit was now inflated as the F-104 continued its ascent. After the flame out Scrappy said all he could hear was the sound of his own breathing. As he approached 90,000 feet, he pushed the stick forward and went over the top indicating a mere 30 knots. Scrappy relayed to the author in 2013, “When I went over the top the sky was a dark purplish-blue and I could see the curvature of the earth. A Lockheed engineer said I could have seen Salt Lake City if my eyes were good enough.”

On his way back down the radar operator at Edwards informed Scrappy he’d topped out at 91,249 feet which shattered the previous record by 14,000 feet. Scrappy turned towards Palmdale; air started the J79 at 47,000 feet, and made an uneventful landing. Later that year Vice-President Richard M. Nixon presented Scrappy with the 1958 Collier Trophy at a dinner in Washington, D.C. A week after Scrappy’s flight, Maj Walter C. Irwin set a world speed record in another F-104, thus making the Starfighter the first aircraft in history to hold world speed and altitude records simultaneously. Irwin’s flight will be detailed in part two of this article.

DECEMBER 13 & 14, 1958- TIME-TO-CLIMB RECORDS

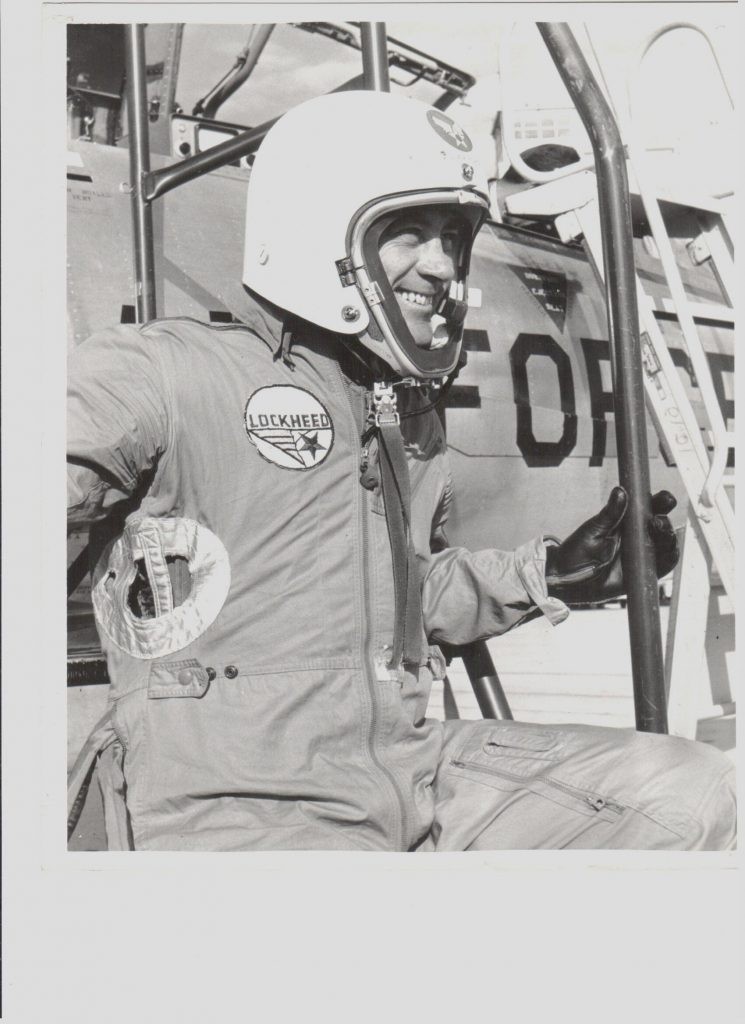

One of the missions the F-104 was designed to perform was that of a point interceptor. To that end Lockheed sought to break, and set, a series of time-to-climb records. The fourth squadron to receive the F-104 was the 538th FIS at Larson AFB, Washington, and the squadron commander selected Lieutenants (Lt) Einar Enevoldson and William Smith for the project. Einar explains, “Lockheed went to the Pentagon and said we believe the F-104 can break some records. Once it was approved the Air Force looked at the records and saw nothing special about them, all were well within the normal operating parameters of the aircraft. So they decided to assign the record attempts to an operational squadron. Our squadron commander said he could do the records himself but he was going to retire soon, so he decided to give them to a junior pilot thinking it might be a career booster. I was pretty junior so I was not one of the first pilots to get checked out. I could have done all the records myself, but Bill and I split them up. I thought the 3,000-meter (9,843ft) and 25,000-meter (82,021ft) records would be the most challenging, so I took those and Bill and I split the rest. Although both men had very little time in the F-104, Smith had 40 hours and Enevoldson a mere 15 hours, when they were selected for the record flights, they would both go on to log over 1,000 hours in the F-104. Enevoldson got a majority of his time as a NASA test pilot at Dryden Flight Research Center and Smith gained his hours as an instructor in Germany.

Although they took dissimilar paths, Enevoldson and Smith found themselves flying together with the F-86D-equipped 538th FIS at Perrin AFB, Texas, a full four years before the squadron received its first Starfighters. In February 2013, both men shared their thoughts about flying the F-104. Enevoldson said, “I’ll tell you that was great, everybody else was flying Mach 1 and we were flying Mach 2! It was so nice to fly and had such tremendous performance.” Smith’s comments put into greater perspective what an aerial anachronism the F-104 really was in 1958, “I thought the F-104 was the greatest airplane ever. It was so far ahead of its time. We were flying Mach 2 while the airlines were still flying propeller driven aircraft.”

After being assigned to the project, the pair went down to Lockheed-Palmdale where they would pick up F-104A 56-0762. This early build Starfighter later achieved fame as the NF-104 that was lost during Chuck Yeager’s ill-fated altitude flight. Enevoldson described the modifications made to the aircraft, “They gave us one with an aluminum tail, which was lighter than the later stainless steel tails. They also took out any equipment we did not need, but they had to be careful because the airplane could end up tail heavy, but it still came out a little tail heavy. When we came back from a flight we had to sit in the airplane until they put some gas in it otherwise it would sit back on its tail! They also increased the engine operating temperature about 15 degrees and increased the afterburner fuel flow by 25 percent.”

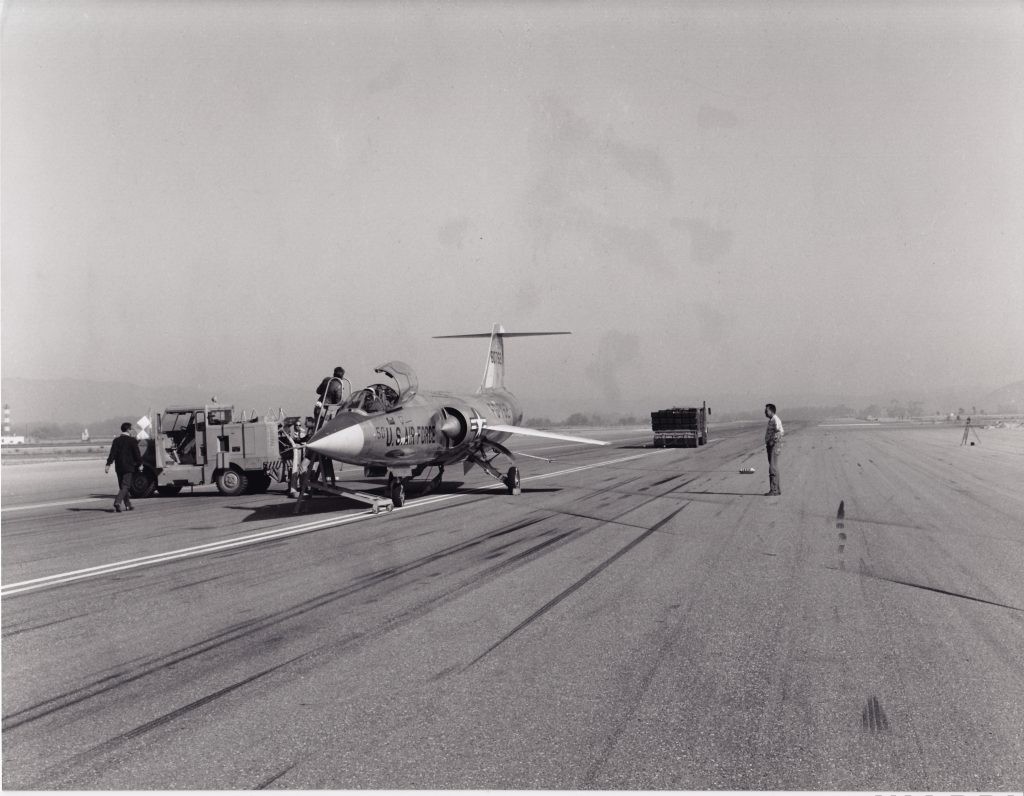

The time-to-climb flights took place at Naval Air Station (NAS) Point Mugu, California because it was at sea level and equipped with missile-tracking radars capable of tracking the F-104 at high altitude. To ensure the Starfighter was making maximum power when it launched the ground crew devised a crude, but ingenious method to hold the F-104 back while Einar and William ran up the power for launch. In today’s over-regulated and over-litigated society this method would not even be considered. Einar describes the launch, “…they removed the drogue chute and installed an explosive bolt in the drogue chute shackle. After the aircraft was towed into position, they had a 300ft cable with one end hooked to that explosive bolt and the other end to a truck loaded with 60,000lbs of PSP matting. We’d start the engine, release the brakes, run the power up to full afterburner and watched the fuel gauge, when it reached the calculated amount of fuel needed for the record plus a little for landing we’d pull the gun trigger on the stick to blow the bolt. For the 3,000-meter (9,843ft) flight I only had 800lbs onboard. When I pulled that trigger the jet really shot out there!” William says, “It was quite an experience. When we pulled the trigger it set off a flash bulb started a movie camera and the timing gear.”

Enevoldson first record flight to 3,000 meters nearly ended in disaster- twice, “We did the 3,000-meter late in the afternoon on the 13th. It was a bit rushed because we could see the fog coming in from the sea. For this flight I’d accelerate to 150 knots, get the gear up and manipulate the stick to keep from scraping the belly while accelerating to 300 knots, and execute a 3G pull and go straight up to 10,000ft. That worked really slick. I was about halfway down the runway when I hit 300 knots and when I pulled up I went right through the fog bank. Because of the altimeter lag and with me being a little slow coming out of afterburner I was at 18,000ft before I Immelmann’d out and rolled upright. When I looked at my fuel gauge, I saw that I had 200lbs of gas and I thought oh that’s not good.

Everything was normal until I was on base leg. It was smoggy and I was looking right into the sun and could not see anything, absolutely nothing that resembled a runway. The fog had really rolled in and gotten thick, so I went down into the shadow of the fog until I was 30 feet above the orange trees. Now in the fog’s shadow I could see better and what I saw was not good. I was very close to the runway and about 1,000ft off the centerline. The airplane was light so I was able to make a hard turn get lined up and touched down. On rollout I went right into the fog bank. That hard turn I made to get on the runway would have been suicide in a standard weight F-104 at that speed and altitude.”

After Enevoldson shut down the ground crew informed him that he narrowly adverted a second disaster. After the launch the driver of the PSP-laded truck started to pull off the runway, but he stalled the engine. During extremely short flight the driver sat helplessly on the runway trying to re-start the stubborn engine. He finally got it started and had just cleared the runway when Einar came screaming in on final approach and into the flare, narrowly missing the unseen truck.

Despite the drama, Enevoldson’s flight was hugely successful. It had taken just 41.85 seconds to go from brake release to 9,842ft, besting the previous records by 4 seconds. The Starfighter was fueled and prepared for Smith’s attempt at the 6,000m (20,000ft) record the next morning. On that flight William climbed to 20,000ft in just 58.41 seconds! He also set new records by climbing to 9,000m (30,000ft) in 81.14sec, and 20,000m (66,000ft) in 222.99 seconds (3 minutes 42 seconds). The latter record and Einar’s final climb to 25,000m (82,000ft) established new records since, at that time, no other aircraft was capable of climbing to the very edges of space.

In 2013, Smith recalled his final flight to 66,000ft and highlights why radar tracking was so important, “For our final flights Einar and I leveled off at 35,000ft to re-accelerate and continue our climb. We chose 35,000ft because it was very cold at that altitude that day. On my flight I accelerated to 1.85 Mach and pulled maybe 1.5Gs until I reached the proper climb angle. We had grease marks on the canopy to help us see the attitude of the airplane, which I think it was about 60 degrees. I don’t remember what my maximum altitude was because the altimeter only went to 65,000ft. Going over the top I flew very gently because I wanted to be sure the tail stayed behind me!” For these high-altitude flights Einar and Bill wore the MC-4 partial pressure suit. To ensure the suit worked properly William dumped the cabin pressure while re-accelerating at 35,000ft.

Enevoldson also vividly recalled his final flight, “The twenty-five-thousand-meter flight was pretty neat I went straight up to 35,000ft and leveled off to re-accelerate. At 1.5 Mach I began a 1.25G pull to a 45-degree climb, but the aircraft had so much power that it would accelerate to Mach 2 during the pull-up! I would hold that climb angle until I went through 82,000ft and while going over the top I held about 2-3 degrees angle-of-attack by which time I was 60-70 miles out to sea. I descended to about 50,000ft and re-started the engine and landed.”

When the numbers came back, they were simply amazing; Enevoldson had gone from brake release to 82,000ft in 266.03 seconds (4 minutes 24 seconds)! That’s nearly an average 21,000ft per minute climb rate, which includes the temporary leveling off to re-accelerate! This performance gave Enevoldson an idea, “On the 82,000ft flight I coasted up to about 90,000ft on the overshoot and thought we should go for an altitude record, which was about 91,000ft at that time. It would not have been hard to do at all. We got Lockheed to make a big pitch to the Air Force to let us go for the altitude record. They hemmed and hawed for a couple days and finally turned us down and Joe Jordan did it a year later.”

DECEMBER 14, 1959- JORDAN EXCEEDS 100,000ft

Scrappy Johnson’s altitude record fell on September 4, 1959, when Communist pilot Vladimir Ilyushin raised the record to 94,658ft in a Sukhoi Su-9. In October 1959, the Air Force Flight Test Center (AFFTC) submitted a formal request for an attempt on Ilyushin’s record. Engineering studies indicated that a modified F-104C had the capability to surpass the Communist record by the required 3 percent. On November 20 a meeting was held at Edwards AFB between LAC, General Electric Company, and AFFTC personnel to finalize planning and coordination for the attempt.

The aircraft chosen for the attempt was F-104C 56-0885, which was flown from Kirtland AFB, New Mexico to Lockheed-Palmdale on November 24, where a modified J79-GE-7 engine was installed. This is the same type engine used in Scrappy’s F-104A, but the engine in ‘885 received considerable modifications by AFFTC Power Branch and General Electric, not the least of which was the maximum RPM, which was set at 103.5 percent, the afterburner fuel control was trimmed to provide 10 percent more fuel flow. There were a few airframe modifications was well, including a larger vertical tail from an F-104B, and extended inlet cones to better position the shock wave at high supersonic speeds.

The aircraft was ready for a shakedown flight by Kitchens (first name lost to history) on December 2 with two more flights the following day. Then on December 6, Commander Lawrence E. Flint, Jr. beat the Communist record when he flew a McDonnell F4H-1 Phantom to 98,557ft as part of Project High Jump. With the record now back in American hands it seemed the F-104 record attempt might be in doubt, but the Air Force was allowed to continue. After all there was more than just U.S. and Soviet bragging rights at stake, there were Air Force versus Navy bragging rights on the line as well.

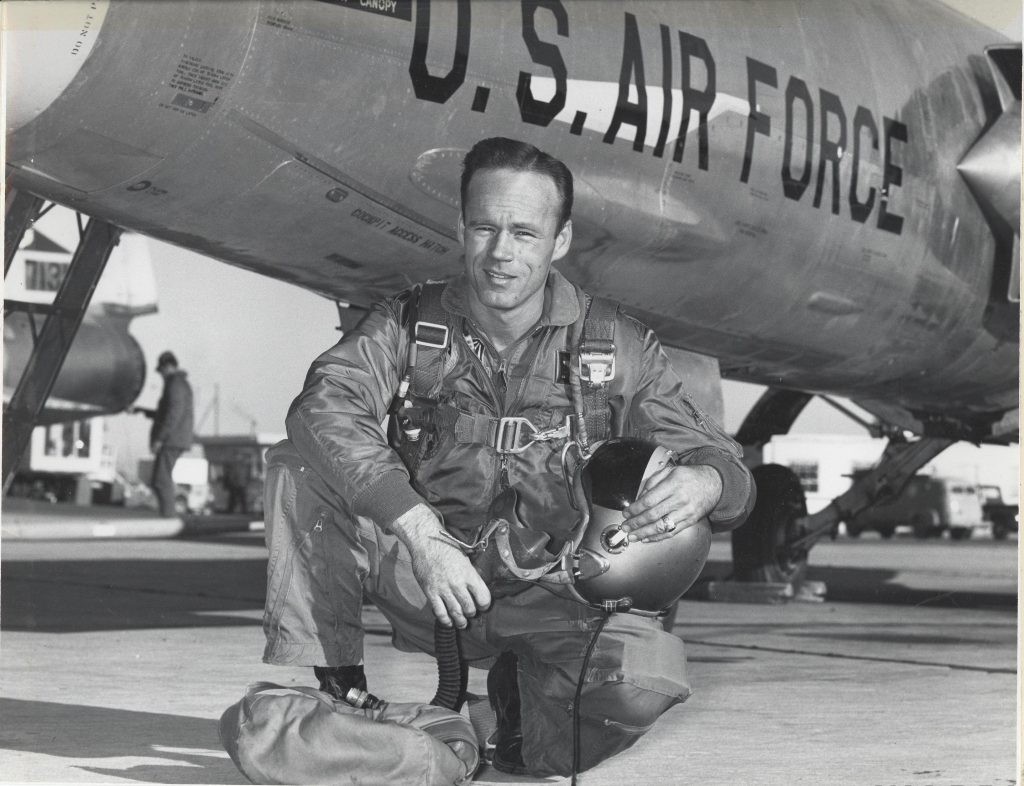

After a four day lay-off Kitchens began flying again on December 7, making five flights over the next three days testing stall characteristics, speed expansion, stability, and zoom climbs as high as 80,000ft. When Captain Joe Jordan made his first flight in the aircraft on December 10, he immediately zoomed to 95,200ft. Sadly, Joe Jordan passed away many years ago, but thanks to an excellent report written by Jordan and Project Engineer Johnny Armstrong we have an excellent narrative on what happened in the cockpit of ‘885 on December 14, 1959.

Jordan flew to a point approximately 80 miles from where he would start the zoom; this would give him adequate space to get the F-104C to its maximum speed. Acceleration was moderate from 0.9 to 1.4 Mach, but then the jet quite literally lept to 2.35 Mach. As Jordan hit 2.0 Mach he dumped the cabin pressure to test his pressure suit and oxygen system, after which he flipped on the constant ignition, minimum fuel reset, and test instruments. At 39,575ft and 2.35 Mach (757.5kts) Jordan began his pull-up, for the first few degrees he only put 1.3G on the airplane but then he rapidly increased the pull to 3.15G until he established a 49.5 degree climb angle. When the afterburner blew-out at 70,000ft Jordan retarded the throttle to military power, but he was still going upstairs like a bat out of hell at 1.78 Mach (305kts). At 81,700ft the J79 finally flamed out and even though Jordan had slowed to 180kts he was still supersonic, 1.42 Mach to be exact, he coasted another 21,000ft until he reached his peak altitude of 103,395ft at which time his indicated airspeed had deteriorated to just 54 knots. At that moment, nearly two and a half years before Yuri Gagarin and Alan Shepard rode their rockets into space, no other human being had flown to such an extreme altitude- an incredible 19.5 miles above mother Earth.

Jordan had just a few scant seconds to take in the heavenly view outside because his flight was only half over. As he went over the top no faster than a Piper Cub, Jordan found that the ailerons had little effect on lateral control, but it was easily controlled with the rudder. At the same time Jordan was riding a fine line of controllability in pitch by holding the stick almost fully aft. If he went too far aft the sticker shaker would activate. Consequently, if the stick went too far forward the F-104 would go into a potentially deadly lateral-directional oscillation. No matter how Jordan moved the stick he noted that it had no apparent effect on the jet’s flight path, it only seemed to rotate around its CG. Once Jordan descended through 70,000ft the aircraft was responding normally, he restarted the engine and landed back at Edwards.

Then it was over. In an amazing 19-month period four pilots had captured nine world altitude records for the Lockheed F-104. In the succeeding decades most of these records fell to other aircraft, but Scrappy Johnson, Einar Enevoldson, William Smith, and Joe Jordan were true aviation pioneers that bravely flew their Starfighters into the unknown upper reaches of the stratosphere. No other aircraft or passage of time can take that away.

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.