For enthusiasts of WWII Japanese aviation, the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California, is where one can find rare examples of Japanese naval fighters and bombers, and one of the rarest yet least appreciated of these is the museum’s Yokosuka D4Y Suisei (彗星, Comet) dive bomber, known to Allied pilots and anti-aircraft gunners as the “Judy”. One of only two remaining examples on display in museums around the world, the Planes of Fame’s D4Y “Judy” has an incredible story of how it went from a rusting hulk to a restored airplane on display for thousands of visitors a year. Even as the prototype for the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service’s newest carrier-borne dive bomber, the Aichi D3A, was beginning its first flight trials, Japanese naval aviation officials knew that with the rapid developments in military aviation around the globe, it was only a matter of time before the new dive bomber would be rendered obsolete. As such, the Yokosuka Naval Air Technical Arsenal (also known as Kugisho from the Japanese acronym for the Aviation Engineering Factory (Kōkū Gijutsu-shō)) was issued for a high-speed dive bomber with a wide-track retractable landing gear, enclosed cockpit, and an internal bomb bay. The aircraft would also be developed to fulfill the role of a carrier-based reconnaissance aircraft.

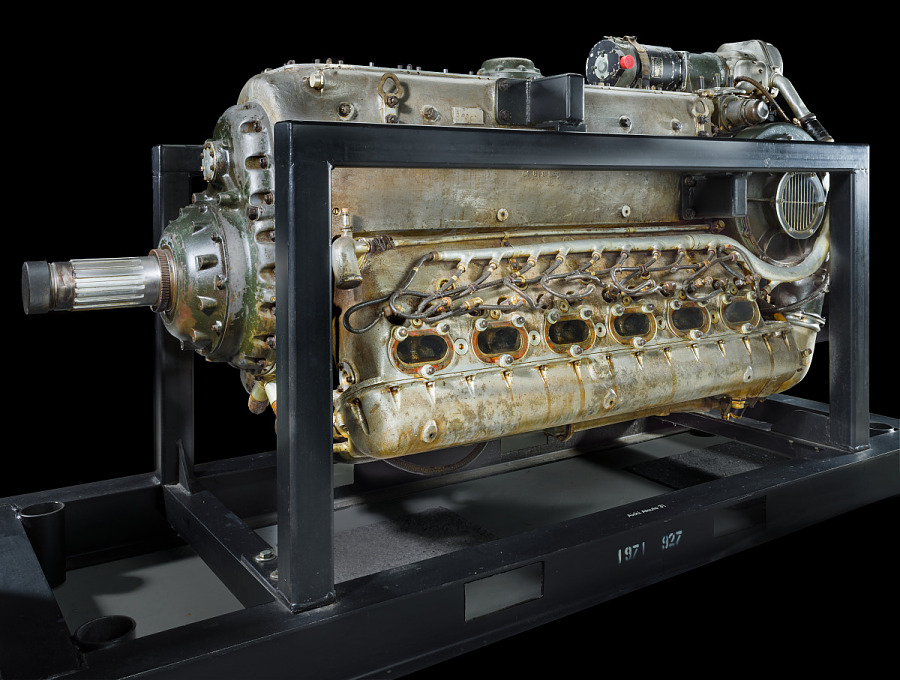

At this time, Japan was still seeking technical expertise in high-performance military aircraft, but although the Imperial Japanese Navy had previously received assistance from Great Britain, Japan’s strategic goals of becoming the next dominant power in East Asia and the Pacific threatened Britain’s colonial possessions, and thus British commercial interests withdrew from Japan. But around this time, Germany, under the influence of the Nazi Party, sought to regain its lost geopolitical influence and saw an opportunity in supporting Japan’s development of new military technologies. By the mid-1930s, they began shipping select aircraft to Japan for technical evaluation. Among the first of these was the Heinkel He 118. This prototype dive bomber was declined by the Luftwaffe in favor of the Junkers Ju 87 “Stuka.” However, two examples were shipped to Japan for testing with the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy, becoming the DXHe1. Though one of these disintegrated from excessive speed during a test dive, it would become a basis for Kawasaki to develop the Ki-32 for the Japanese Army Air Service, and for Yokosuka to build the D4Y. Unusually for a carrier-based aircraft, it was decided to power the Yokosuka D4Y with a liquid-cooled inline engine as opposed to an air-cooled radial engine. Though the growing convention around the world among navies was to power their aircraft with radial engines that were more durable and did not require complex radiators, an inline engine offered more power for high-speed flight, and with the right design, would present less frontal area than a conventional radial engine, reducing drag on the airframe. The engine that would be selected to power the new Japanese naval dive bomber was to be the Aichi Atsuta, a licensed copy of the Daimler-Benz DB-601 inverted V12 engine used on German combat aircraft such as the Messerschmitt Bf 109E. Daimler-Benz had sold Aichi a production license for the engine, as well as Kawasaki, which developed the engine as the Ha40 for the Japanese Army.

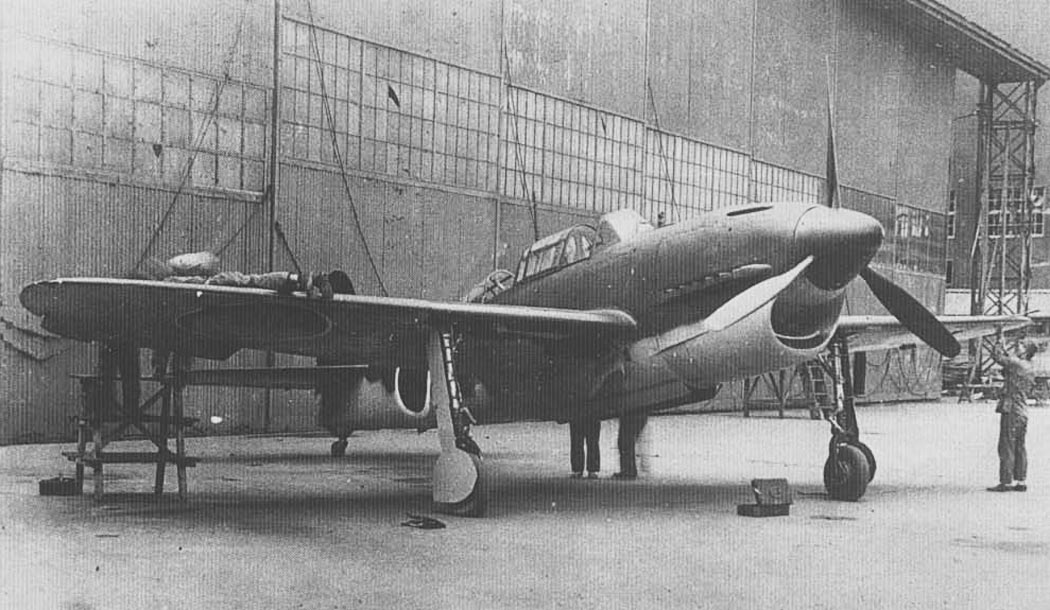

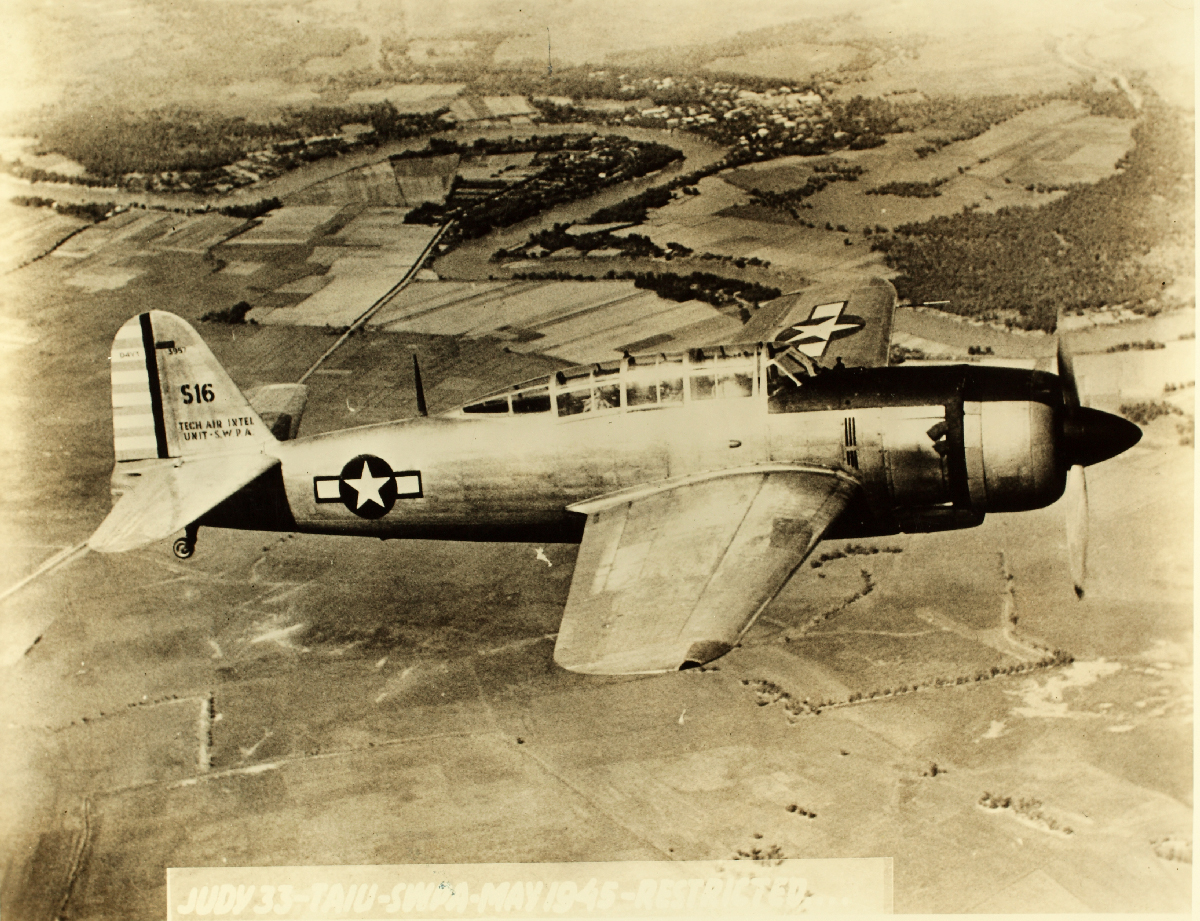

The first prototype of the Yokosuka D4Y was completed by November 1940 and was first flown before the year was out. The aircraft was officially designated as the Suisei (彗星, Comet) by the Japanese. Still, when American air intelligence units learned of the type, the new dive bomber was given the American reporting name “Judy” in keeping with the Allied custom for giving Japanese fighters Western boys’ names and bombers and transports Western girls’ names for identification by Allied pilots and anti-air gunners. The type’s combat debut would take place during the Battle of Midway, when two pre-production D4Y1-C photo-reconnaissance examples were assigned to the carrier Soryu. However, the loss of all four Japanese fleet carriers also resulted in the loss of these two aircraft.

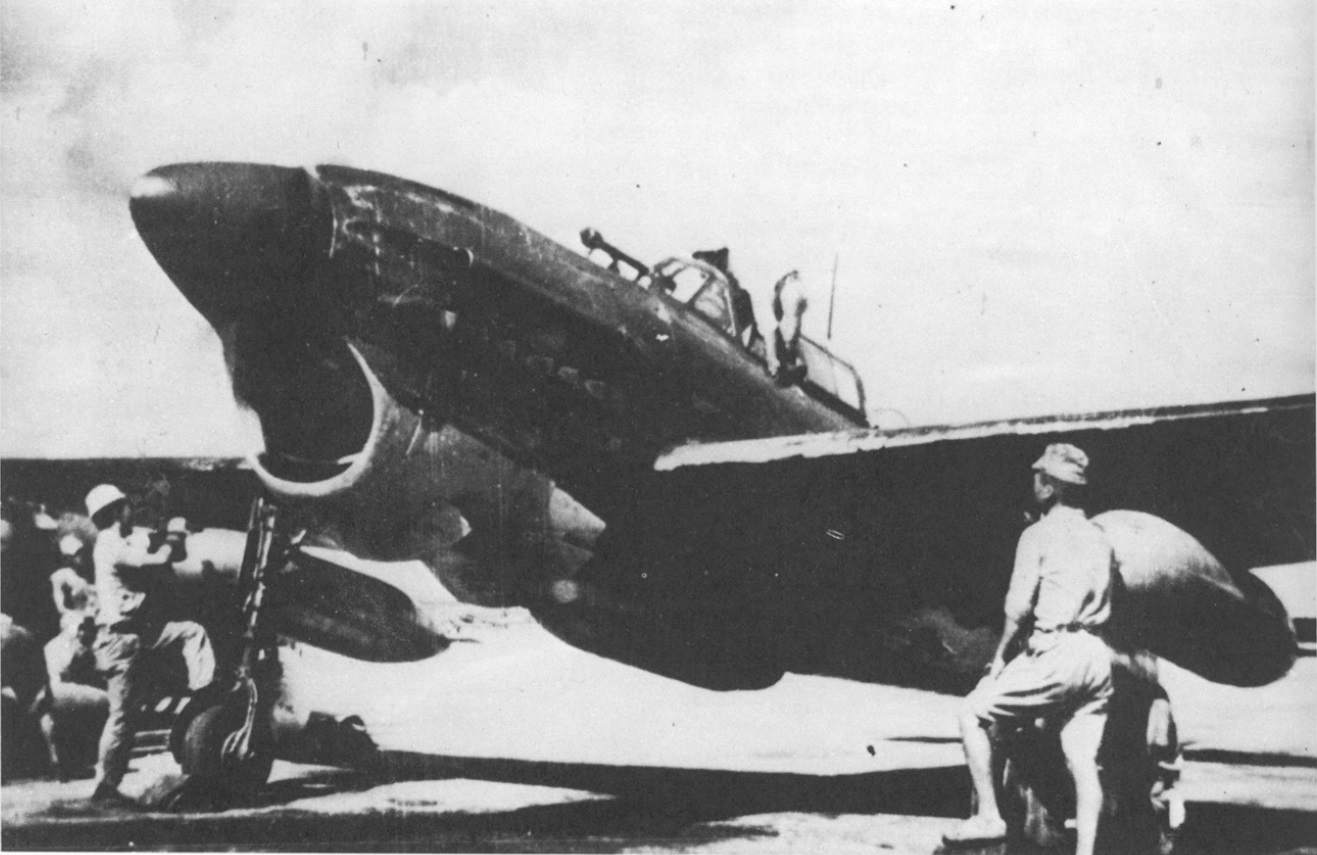

Nevertheless, even as the Japanese began losing their fleet carriers against American air and submarine attacks, the Yokosuka D4Y Suisei was inducted into numerous Japanese naval air groups across the Pacific. By 1943 and 1944, though, the Americans had shot down much of Japan’s veteran pilots, and were now fielding new carrier fighters such as the Grumman F6F Hellcat and the Vought F4U Corsair that could easy catch up to the “Judy”, and since the D4Ys lacked pilot armor and self-sealing fuel tanks, they were often shot down in flames, such when hundreds of Yokosuka D4Ys were shot down during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, which came to be known among American pilots as the Marianas Turkey Shoot.

As the war progressed, the difficulty in manufacturing Aichi Atsuta engines under wartime conditions and the need for a Japanese-designed engine more serviceable to frontline mechanics led to the installment of the Mitusbishi Kinsei (金星, Venus) 14-cylinder, air-cooled, twin-row radial engine on the D4Y3 Model 33 variant, which was to become the version of the “Judy” most associated with the latter half of the Pacific War. By late 1944, Japan’s desperate position against the overwhelming numbers of American equipment in the face of a string of catastrophic defeats from the Solomons to the Philippines and the introduction of B-29 Superfortress bombing raids against the Japanese home islands would see Japan invoke the Special Attack Units, better known as Kamikazes.

The final year of WWII would see hundreds of D4Y Suiseis and other types attempt to destroy American warships through both suicide attacks and conventional dive-bombing attacks. Indeed, a lone D4Y was responsible for the light aircraft carrier USS Princeton (CVL-23) on October 24, 1944, and on March 19, 1945, another single Yokosuka D4Y Suisei severely damaged the Essex-class carrier USS Franklin (CV-13), which despite the loss of 807 crewmen and the entire ship being burned from bow to stern, managed to survive this encounter and return to the United States, where it was still under repair when the war ended. Additionally, some examples of the Suisei were even equipped as night fighters to intercept B-29s over Japan with a 20 mm Type 99 cannon installed in a slanted forward position in the rear cockpit, but with no onboard radar and a slow climb rate, they proved to have little effect on the success of the nocturnal raids by American Superfortresses.

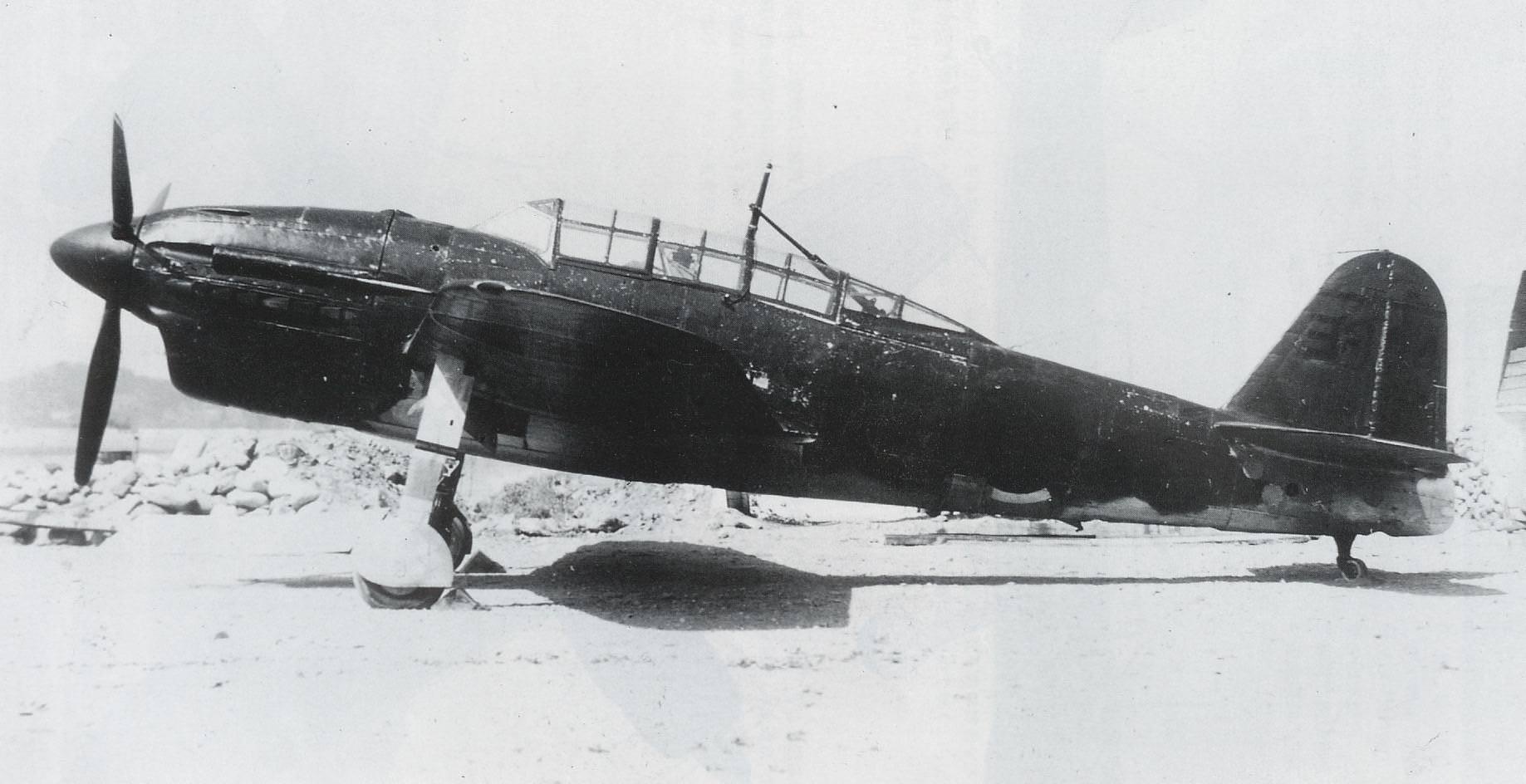

When the surrender of Japan came on August 15, 1945, all remaining Japanese aircraft were grounded, and some examples of Yokosuka D4Ys were shipped to the United States for technical evaluation. Some data had already been acquired through at least one example that was captured in January 1945 at Clark Field in the Philippines that was flight tested in the Philippines by the Technical Air Intelligence Unit–South West Pacific Area (TAIU-SWPA). With the aircraft being considered obsolete and Japan being completely disarmed, all Yokosuka D4Y Suiseis that survived the war intact were scrapped, with no one being spared for any museums in Japan or the United States. Though books on and scale model kits of the aircraft would be made in the postwar years, it would be decades before aviation history enthusiasts on both sides of the Pacific looked to the war wrecks of the Pacific to find examples that could be recovered and restored for display in museums.

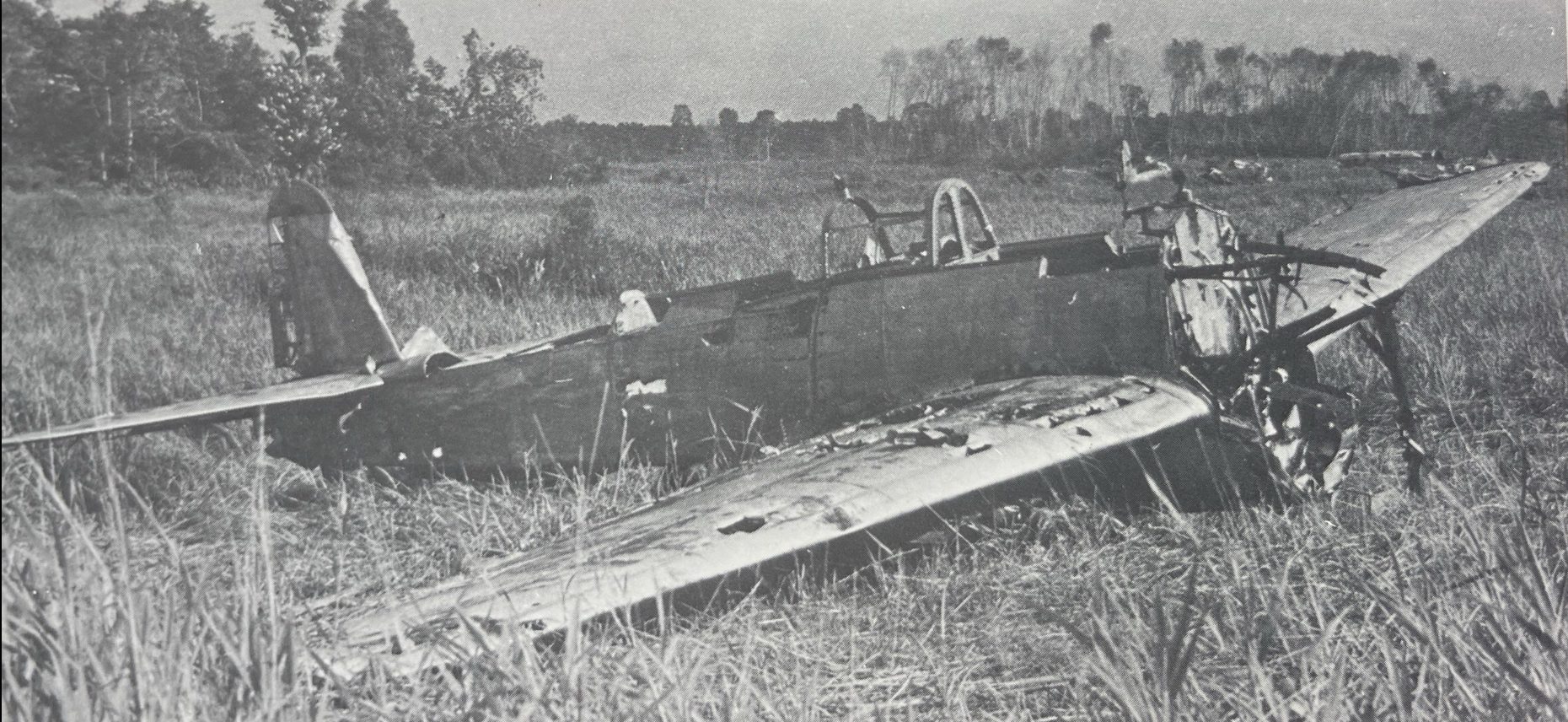

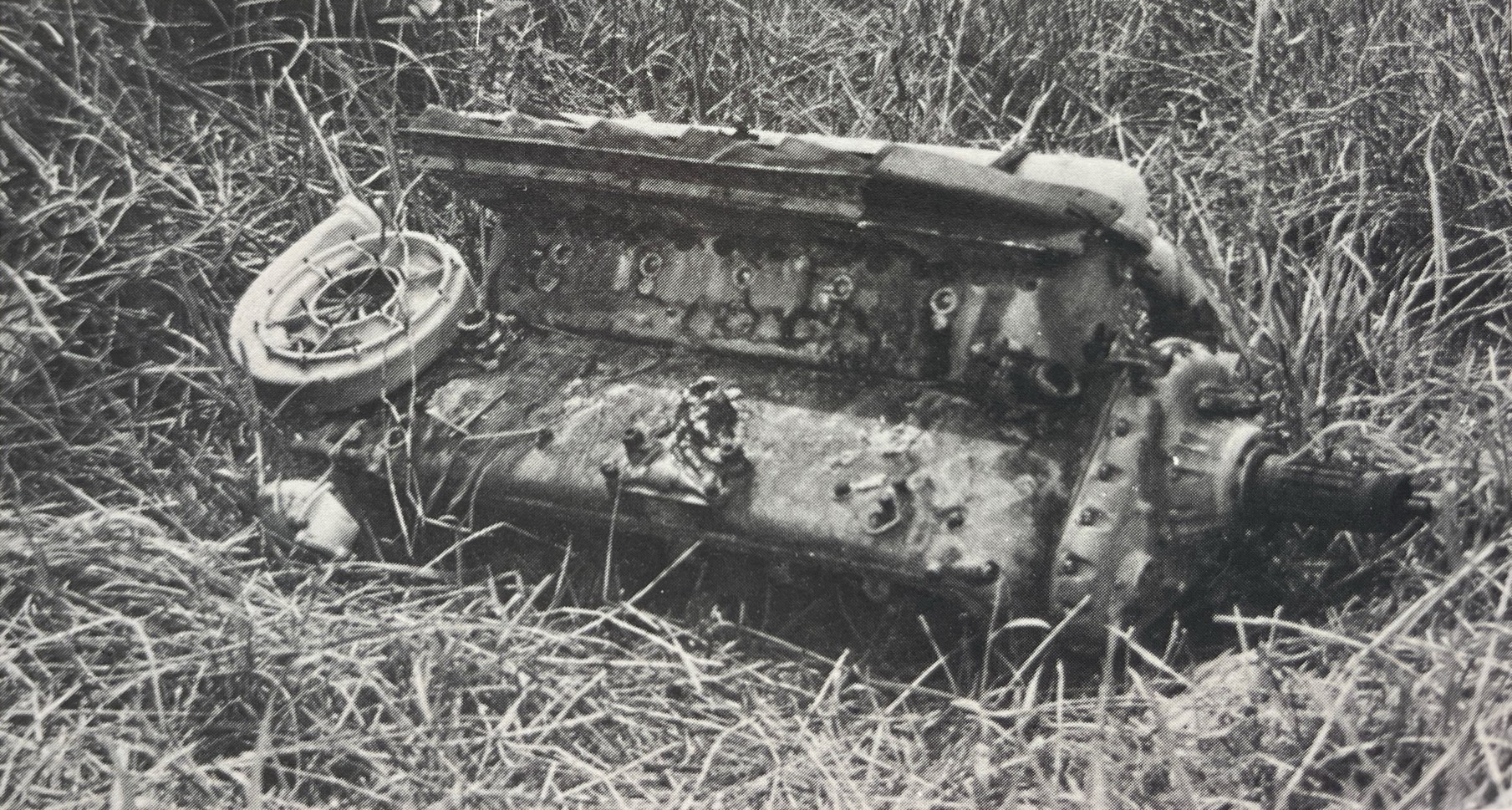

Much of the work on establishing the historical provenance of the D4Y “Judy” now on display at the Planes of Fame Air Museum has been a challenge, to say the least, but based on fragmentary evidence left behind, this is the best estimation of the aircraft’s mysterious past. As early as 1973, the aircraft had become known to the growing community interested in documenting and recovering aircraft wrecks from the South Pacific and Southeast Asia, when expatriate Roy Worcester surveyed the disused Babo Airfield in the West Papua province of Indonesia (formerly Dutch New Guinea). Worcester photographed the wreck of the Suisei, noting that the aircraft’s right side landing gear had collapsed, but its left side gear remained standing. The aircraft’s Aichi Atsuta V12 engine had been detached by the Japanese during the war, but a discarded Atsuta, quite possibly from the aircraft itself, lay nearby in the tall grass.

Faded stencils and corroded data plates on the aircraft would provide a clue to the aircraft’s identity, with researchers Jim Long and Jim Lansdale taking the lead on this effort. The aircraft was determined to have been a D4Y1 Model 11, and researcher Jim Long would be quoted by the website Pacific Wrecks as identifying the aircraft as serial number 7483, which was assembled in the Yokosuka factory in February 1944. There has been no documentation to confirm which exact Kōkūtai (Naval Air Group) D4Y1 s/n 7483 served in, but it is clear that the aircraft was abandoned on Babo Airfield, likely the result of combat damage that could not be repaired in the field. Though other stencils from the factory were found on the aircraft, most experts have come to accept that s/n 7483 is the correct identity for this Suisei. With the publication of numerous books and magazine articles on the WWII aircraft wrecks in New Guinea, museums around the world looked to Babo Airfield to recover the wrecks of rare Japanese WWII aircraft. After the Indonesian Air Force Museum (Dirgantara Mandala) recovered a Kawasaki Ki-48-II twin-engine bomber (Allied reporting name “Lily”), Mitsubishi A6M5 Model 52 Zero, Nakajima Ki-43-II “Oscar”, and Mitsubishi Ki-51 “Sonia” reconnaissance bomber from Babo Airfield, other museums and collectors around the world gained interest in Babo Airfield. In 1991, the Museum of Flying in Santa Monica (which later closed in 2002 before reopening as a smaller facility in 2012) hired aircraft salvager Bruce Fenstermaker to retrieve the wrecks of a few Japanese aircraft from Babo and ship them to Los Angeles. At Babo, Fenstermaker selected the Yokosuka D4Y1 Model 11 found there, along with a Mitsubishi A6M3 Model 22 and A6M3 Model 32 Zero (both of which would be used as patterns for the construction of three airworthy Zeros in Russia that were shipped back to the United States), a Kawasaki Ki-61 Hien (Tony) fighter and a Mitsubishi G4M1 Model 11 “Betty” bomber, which were disassembled and placed in shipping containers for the long journey across the Pacific to the Museum of Flying at Santa Monica.

Between 1997 and 1998, though, the remains of the Yokosuka D4Y1 and the Mitsubishi G4M1 “Betty” were sold to the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino. The “Betty” would be displayed as part of a crash diorama in the Planes of Fame’s Foreign Hangar until November 2015, when the aircraft was sold to the Flying Heritage and Combat Armor Museum of Everett, Washington. Despite online speculation over the FHCAM’s possible plans of displaying the aircraft, the Betty has remained in storage to the present day. In contrast, the wreck of the “Judy” dive bomber was shipped to the Planes of Fame’s satellite location in Valle, Arizona, situated 28 minutes south of the Grand Canyon. There, the D4Y was displayed unrestored during the 2000s, but in the spring of 2009, the wreckage was transported once more to Chino Airport, this time to be rebuilt as a fully intact aircraft. Though the museum still had the aircraft’s original Aichi Atsuta inverted V12 engine, it was decided to rebuild the aircraft to appear as a radial-equipped D4Y3 Model 33, as no example of this variant has survived the war. But without a Mitsubishi Kinsei engine, it was decided that an American radial engine of similar size and power output would be installed, with the Planes of Fame deciding that a Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial engine, which is also a 14-cylinder, twin-row radial engine, and examples of this powerplant have been used in the construction of three Zero reproductions assembled in Russia during the 1990s and early 2000s, and in the Mitsubishi A6M3 Model 32 Zero s/n 3148 that has been rebuilt for the Military Aviation Museum by Legend Flyers of Everett, Washington.

By November 2010, the fuselage was completed inside the workshop of Fighter Rebuilders, the restoration firm run by Steve Hinton within the grounds of the Planes of Fame Air Museum. The restoration of the wings, however, would continue. Though the wings were given new sheet metal, the corroded wing spars ensured that the aircraft could not be restored to airworthy condition without building a new set of spars for the wings. But the aircraft would not entirely be a static restoration, as the R-1830 Twin Wasp radial would be operational to allow the aircraft to complete taxi runs at the museum’s airshows held at Chino Airport. On November 3, 2011, restoration volunteers mated the restored fuselage back onto the restored wings of D4Y1 s/n 7483. By January 2012, the R-1830 engine had also been installed, and work began on connecting fuel lines, control cables, and engine throttle and exhaust systems (the museum produced a short video of the aircraft during its restoration HERE).

In the spring of 2012, the aircraft was structurally complete but was still in bare metal by the onset of the 2012 Chino Airshow hosted by the Planes of Fame. Here, the Suisei was displayed on the flight line, with the fuselage and wings bearing the Hinomaru (Rising Sun emblem), and given red paint for the tips of its three propeller blades. For many enthusiasts, though, the chance to see a Yokosuka D4Y was an incredible opportunity that could not be seen anywhere else in the US. After the airshow, work resumed on the aircraft, this time to paint it in a proper IJNAS scheme.

Given the fact that there are no surviving records to say what unit the museum’s “Judy” was assigned to, and that the aircraft was now configured to appear as a D4Y3 Model 33, it was decided to paint the aircraft in the markings of the 601st Naval Air Group, and so the aircraft adopted the tail code 601-35. When the next Chino Airshow came in the spring of 2013, the aircraft was once again brought to the flightline and was also taxied before the thousands of spectators who came to the show.

Today, D4Y1 Model 11 s/n 7483 remains on display inside the Planes of Fame’s Foreign Hangar, where it sits nose to nose with the museum’s Mitsubishi J2M3 Raiden (Thunderbolt, Allied reporting name “Jack”), which was covered in a previous article HERE, and also rests behind the museum’s Mitsubishi A6M5 Model 52 Zero (also covered HERE). The aircraft may not be airworthy, but it remains a draw for WWII Japanese aviation enthusiasts, and many visitors from Japan have come to see it and the other WWII Japanese aircraft at Chino.

In addition to this example at Planes of Fame, there is only one other Yokosuka D4Y Suisei on display anywhere else in the world. This is D4Y1 Model 11 serial number 4316, which was shipped to Colonia Airfield on Yap Island, Micronesia, where it was abandoned along with other Japanese aircraft wrecks following American raids during WWII. Its presence on Yap Island first came to prominence in 1972, with the wreck laying just off the old runway. Eight years later, in 1980, Japanese enthusiast Nobuhiko End led an effort to recover s/n 4316 from Yap Island and return it to Japan. The operation was funded by Nippon Television in an effort to produce a documentary feature about the recovery of the Suisei. Upon its return to Japan, the aircraft was brought to Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF) Camp Kisarazu, which had served as a Japanese naval air station during WWII, where parts from at least two other Suisei wrecks were used to complete the airframe. Upon completion, the aircraft even completed an engine run at Kisarazu with a restored Aichi Atsuta engine and is now on display inside the Yūshūkan museum located inside Yasukuni Shrine in Chiyoda, Tokyo.

For more information, visit the Planes of Fame’s website HERE.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.