In the shadow of Mount Fuji, an incredible museum, known for being open only one month of the year is set to open once more this year, The Kawaguchiko Motor Museum/Fighter Museum is known for its unique collection of both airplanes and automobiles that is run by Mr Nobuo Harada, a former race car driver from Tokyo turned automotive businessman specializing in importing and exporting cars. Like a delicate mountain flower, the museum is only open seasonally, but for those lucky enough to make it out there, they will be in for one of the most impressive private collections of WWII aircraft in Japan.

While Nobuo Harada may have amassed his fortune through automobiles, which are certainly well-represented at the museum, Harada has also been interested in aviation since his childhood in Japan during World War II. Like many Japanese who lived through WWII, the war certainly left its mark on Harada. At the age of seven, he lost his Tokyo home to U.S. air raids. Nevertheless, Harada was inspired to use the connections he made from importing and exporting cars to fund operations to recover abandoned WWII Japanese aircraft wrecks from across the Pacific, setting his sights on Yap Island in the Federated States of Micronesia.

There, several Japanese aircraft wrecks lay in the area around Yap International Airport, which was originally constructed by the Japanese during WWII. Due to the presence of the nearby settlement Colonia, American forces called the airfield Colonia Airfield, and from April to August 1944, they launched bombing raids on the airfield, using both carrier-borne US Navy aircraft and Consolidated B-24 Liberators of the US Army Air Forces.

In 1980, a recovery team funded by Nobuo Harada recovered the wrecks of four Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters (A6M2 Type 21 construction number 91518, A6M2 Type 21 c/n 92717, A6M5 Model 52 c/n 1493, and A6M5 Model 52 c/n 4708) to be restored for display in Japan. Over the years, Harada and his team of restorers worked to bring the Zeros back to static display condition. Eventually, the restored A6M5 Zero c/n 4708 would be donated to the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Museum in Komaki, Aichi Prefecture. Harada’s team also helped rebuild the A6M5 Zero now on display in the Yūshūkan museum within Yasukuni Shrine (Mitsubishi A6M5 Model 52 Zero c/n 4168, tail number 81-161 (recovered from Rabaul in 1974 and restored using parts from A6M5 Zero c/n 4241). Additionally, Yūshūkan also features Yokosuka D4Y1 Suisei (Comet; Allied reporting name “Judy”) c/n 4316, which was restored at Kisarazu Airfield near Tokyo following its recovery from Yap Island.

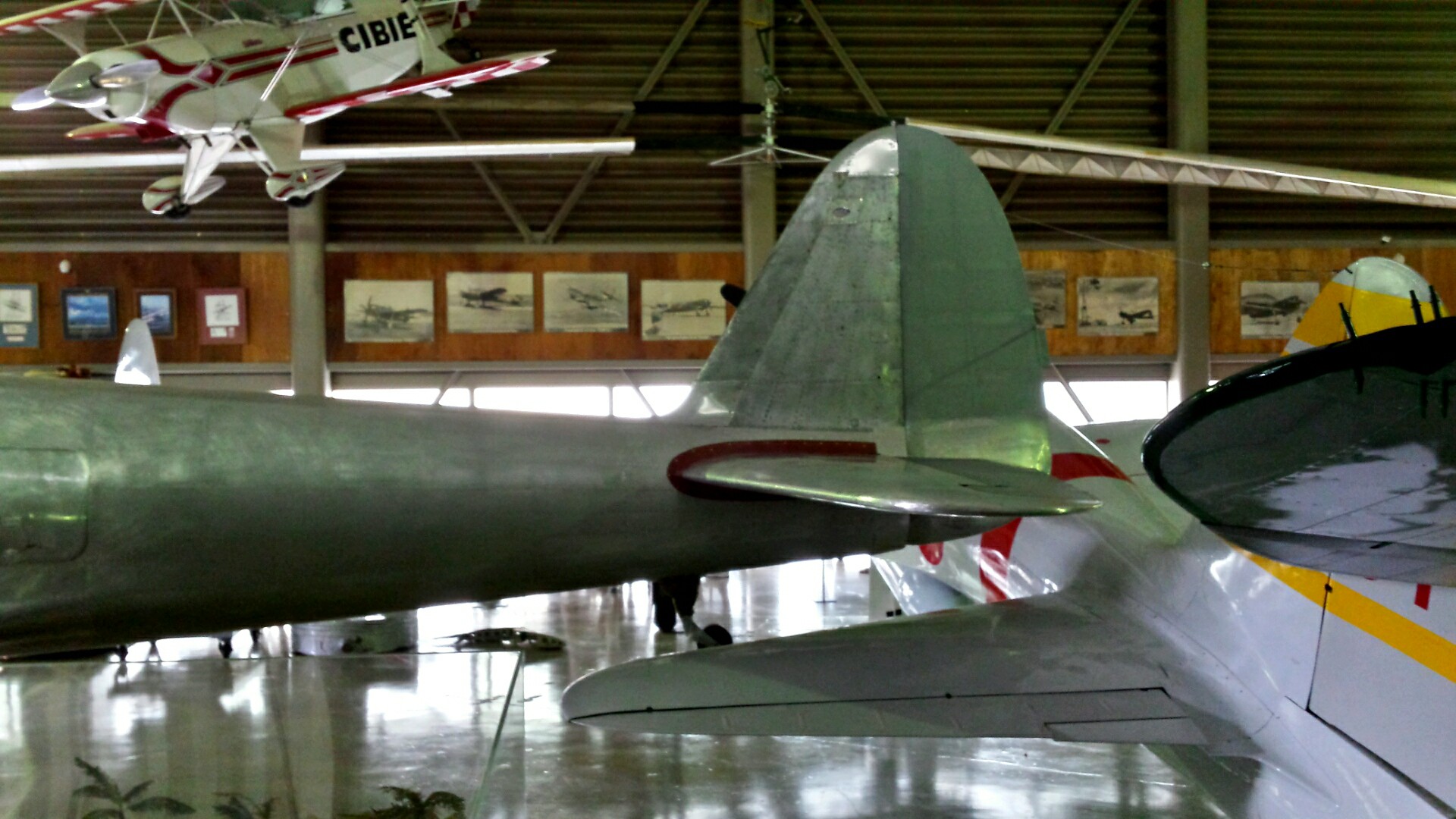

Meanwhile, the Kawaguchiko Motor Museum/Fighter Museum, which was opened in 1981, now features three of the Zeros recovered by Harada from Yap: A6M2 Type 21 Zero c/n 91518 and A6M5 Model 52 Zero c/n 1493 have been fully restored, while A6M2 Type 21 Zero 92717, having used as a source of parts for other Zero restorations, has been mostly reassembled, though it is displayed without its aluminum skin, exposing the structure of the fuselage, wings, and tail to visitors.

Back in 2013, when Vintage Aviation News was still called Warbirds News, we covered the restoration efforts of the Kawaguchiko Motor Museum/Fighter Museum to restore a Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa (Peregrine Falcon; Allied reporting name “Oscar”) fighter HERE. We are pleased to report that since that article was published, the Kawaguchiko Motor Museum/Fighter Museum has two restored examples of the Ki-43 fighter on display. While some examples of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force’s most widely deployed fighter of WWII have survived outside Japan in the United States, Australia, and Indonesia, with a few reproductions produced in the postwar years (including one created for the 2007 Japanese film For Those We Love that is now on display at the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots in Kagoshima Prefecture), there were no original examples of the Hayabusa on display in Japan. Nobuo Harada and his restoration team sought to change that by purchasing a salvaged wreck captured by the Royal Australian Air Force in New Guinea in January 1945, which had been stored in a British museum until Harada acquired it. The wreck was then returned to Japan in July 2013.

Since then, Harada and his team have restored two examples that represent two distinct variants of the Ki-43. One is a Ki-43-I and the other is a Ki-43-II, with the -I model having a two-bladed propeller and the -II model a three-bladed one. The Ki-43-I on display is painted in the markings of the aircraft flown by Takeo Kato, commanding officer of the 64th Sentai and an ace with 18 victories before he himself was shot down and killed on May 22, 1942, while attacking a flight of Bristol Blenheim bombers over the Bay of Bengal. The Ki-43-II on display is currently displayed in its bare metal, save for some yellow horizontal stripes on the leading edges of the inboard wing and the Hinomaru (Rising Sun) roundels on the wings and fuselage of the Hayabusa. However, with restoration work being carried out when the museum is closed to visitors, its appearance may have changed since the museum’s last open season in August 2024.

One aircraft that has gained the museum a great deal of attention, even in Western aviation circles, is the existence of the Kawaguchiko Motor Museum/Fighter Museum’s Nakajima C6N Saiun (Iridescent Cloud) reconnaissance aircraft, also known by its Allied reporting name as “Myrt”. The C6N was deployed to be a high-speed, carrier-borne reconnaissance aircraft for the Imperial Japanese Navy, and was first flown on May 15, 1943. By the time the Saiun entered operational service in 1944, most of Japan’s carriers had been sunk either by US Navy bombers or by American submarines.

As such, the aircraft’s combat operations were primarily conducted from land bases. Nevertheless, the aircraft’s top speed of 380 mph at 20,000 feet made the Saiun’s speed nearly equal to that of the Grumman F6F Hellcat, rendering the “Myrt” a difficult prize for American carrier aircraft to intercept. In one famous incident, the crew of a C6N sent the following message through Morse code back to their base: “No Grummans can catch us.” Six examples would even be modified to become night fighters, with either two 20 mm Type 99-1 cannons or a single 30mm Type 2 cannon placed in the observer’s seat, though the aircraft was hampered by the lack an onboard radar unit. However, the C6N’s speed could not win the war, and in fact, it would be an example of this high-speed aircraft that would represent the last Japanese aircraft shot down on August 15, 1945, just five minutes before Emperor Hirohito declared Japan’s surrender.

Today, an example of the Nakajima C6N1 night fighter variant captured in Japan in 1945 and brought to the USA for evaluation is held in storage at the National Air and Space Museum’s Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration, and Storage Facility in Suitland, Maryland, while the submerged wreck of another C6N rests at the bottom of Chuuk Lagoon (formerly Truk Lagoon). The example under restoration at the Kawaguchiko Motor Museum/Fighter Museum was abandoned at the end of WWII at the southwest corner of Moen No. 1 Airfield (Chuuk International Airport) on Weno Island (called Moen Island during WWII). Dick Williams, a former teacher and resident of Micronesia, recalled seeing the aircraft on the site Pacific Wrecks: “When I was there in 1969-70 she was still up on her gear. Clearly a Japanese plane because of the reddish primer, while US planes used zinc chromate.” According to Pacific Wrecks’ webpage on the aircraft HERE, the aircraft remained in situ until it was salvaged and stored by a local, who sold it to a private owner in the United States, who later sold the remains of the Nakajima C6N Saiun to Nobuo Harada in 2015. In August 2023, the unpainted fuselage of the C6N was placed on display for the public, and further restoration of the aircraft will continue in the coming years.

Yet another incredible piece of WWII Japanese military aviation on display in the museum is the restored fuselage of a Mitsubishi G4M1 Navy Type 1 attack bomber, better known to American enthusiasts by its Allied reporting name: Betty. The G4M was the Japanese Navy’s primary land-based, twin-engine bomber for much of WWII, and was commonly named by its flight crews as the Hamaki (“cigar”), both due to the cylindrical shape of its fuselage and for the aircraft’s tendency to catch fire after being hit by enemy fire. The aircraft was also used as a transport aircraft, and in this guise, it was the aircraft type in which Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was shot down and killed by American P-38 Lightning fighters as part of Operation Vengeance.

Today, there are no complete, restored examples of any Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers in either Japan or the United States. However, during the 1980s, Harada recovered the tail of a G4M2 Model 22, c/n 12017, from Yap Island, where he had previously recovered the A6M Zeros, which were restored for display in his museum. While the restoration of the G4M’s tail was completed by 1998, Harada wanted to add to the aircraft by reconstructing the rest of the bomber’s fuselage. Using period photos and plans as reference material, along with notes regarding the wrecks of other G4Ms, Harada and his restoration team built a new forward section to attach to the restored tail of G4M2 12017. Today, the hybrid sits proudly on display at the Kawaguchiko Motor Museum/Fighter Museum and is often another highlight for both local and foreign visitors.

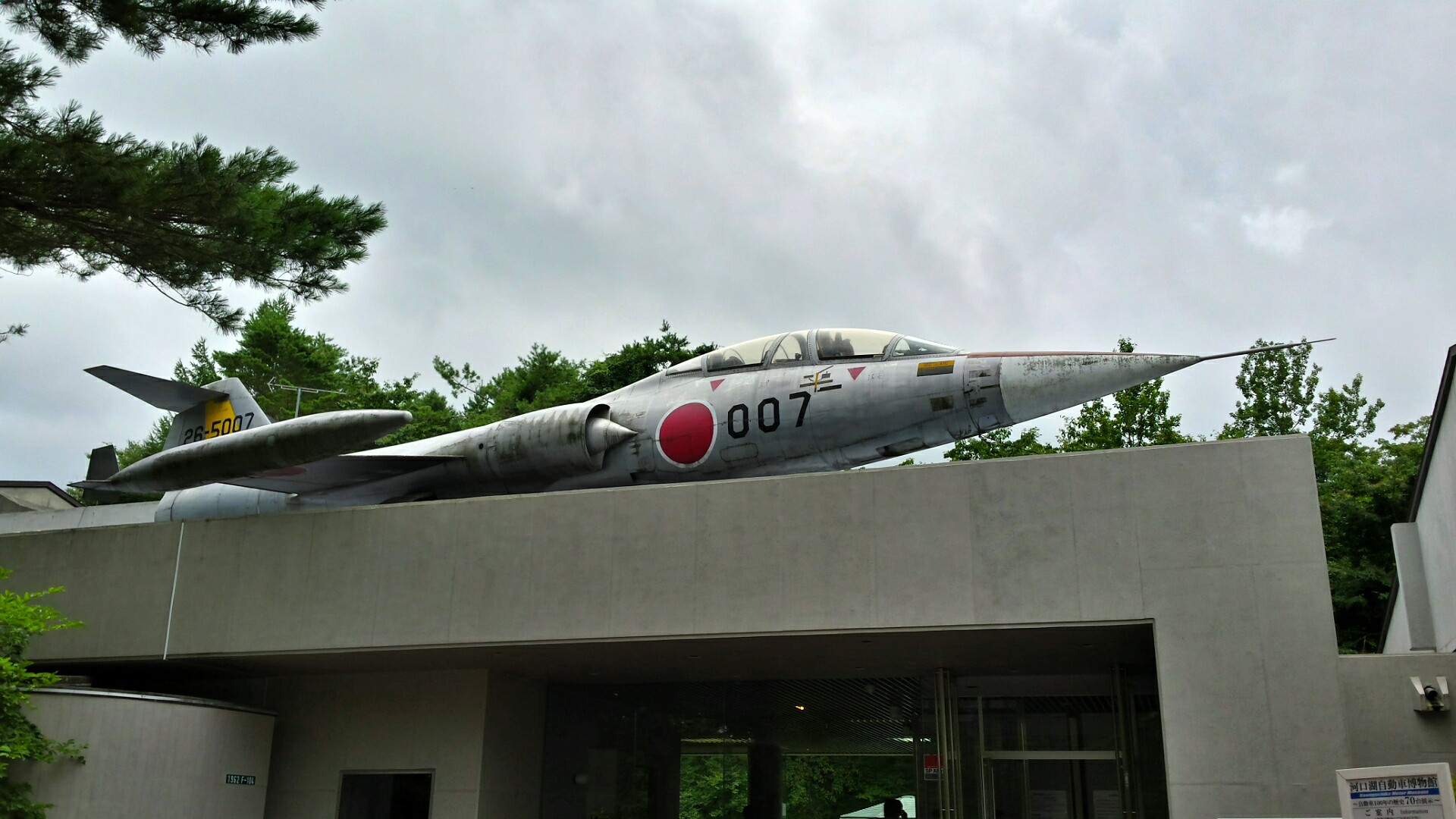

Other aircraft on display include replicas of the 1903 Wright Flyer, a Yokosuka E5Y biplane trainer (Allied reporting name “Willow”), and a Yokosuka MXY-7 Ohka kamikaze rocket, along with several post-WWII designs displayed outdoors. Many of these are aircraft that were once part of the Japan Air Self Defense Force (JASDF), such as a Curtiss C-46 Commando, North American F-86F Sabre, Lockheed T-33 trainer, forward section of a Grumman S2F Tracker, fuselage of a Sikorsky H-19 helicopter, North American T-6 Texan, and Lockheed F-104 Starfighter, with other aircraft held in storage.

Besides complete and partial airframes, the museum’s aviation collection also includes a number of engines, propellers, and mementos from pilots. In a 2013 article for the Japan Times, Nobuo Harada made his motivation for maintaining Japan’s WWII aviation history very clear: “Stories of the war will be forgotten in 30 years. It’s now or never.”

As previously stated, the Kawaguchiko Motor Museum/Fighter Museum is only open during August, with operating hours from 10am to 4pm. If you do make it to Japan during August, be sure to put this museum on your itinerary. For more information, visit www.car-airmuseum.com.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.

Very interesting report. Until today I didn’t hear about mission of Harada San!

Thank you and bast regards

Enthusiast and frquent visitor of Aviation Museum and sits arund the world

Bogdan from Warsaw, Poland

Great article thanks! Quite rare aircraft one of which i had not heard of. I hope I can visit one day to see it.

I was born in 1960, 15 years after “the war” in North Queensland. My parents grew up during the conflict. The shadows of the war permeated Australian society with a haze of anti Japanese feeling. My father took me aboard a Japanese sugar ship at Lucinda Point Sugar terminal when I was three and I remember the crew smiling and waving to me. I am very glad that the old sentiment is, almost, all gone now.

I hope too, never again.