Many of us have heard the expression “looks aren’t everything.” A similar anecdote would be ”you can’t judge a book by its cover.” A person, place, or thing cannot be considered for what first appears to the naked eye. We must take time to foster a relationship with that which our eyes first deem as “ugly” or an-aesthetically displeasing. In many sectors of aviation, praise is placed on attractiveness. Clean-cut airline captains, luxury crew cars at the fancy FBOs, the design of business aircraft themselves (and don’t get me started on warbirds!) What many fail to recognize is that beauty is often beneath the surface. With Piper Aircraft’s PA-22 Tri-Pacer, the beauty is found by physically flying the aircraft.

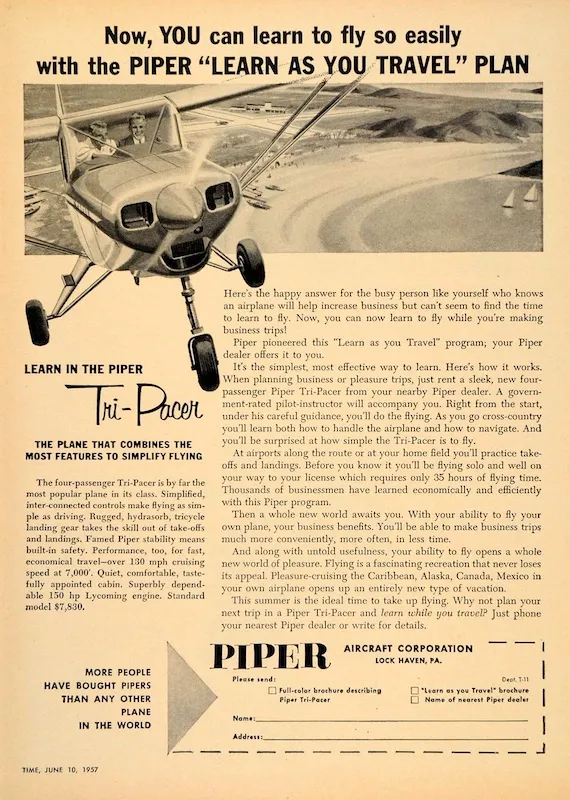

The story of the Tri-Pacer begins in November of 1947. It was at this time that Piper’s PA-15 Vagabond first took flight. The PA-15 was a two-place taildragger with side-by-side seating. From the Vagabond evolved the Piper PA-20 Pacer. The PA-20 took the PA-15 design and added a rear seat to accommodate two more passengers. The conventional-geared Pacer was certified as airworthy on December 21, 1949. One year later, the PA-20 would again be modified. This time, a nose-wheel was added by Piper to turn the Pacer into a tricycle-gear aircraft. The selling point from Piper Aircraft at the time was that this nose-wheel made the aircraft simpler to fly, and thereby safer and more accessible. The goal was to market to the “everyday” flyer who needed a simple, “no-fuss” aircraft.

Piper’s modifications to the PA-20 Pacer resulted in the PA-22 Tri-Pacer. The PA-22 has a distinct look about it; the addition of the nose wheel was done without many other alterations to the airframe. As a result, the aircraft looks like a stool with wings, hence the moniker “flying milk stool.” The original PA-22 had a 125 horsepower Lycoming O-290-D engine. In 1952, the PA-22-150/160 was released with a 150 or 160 horsepower Lycoming O-320-A2A/A2B engine. A variant of the Tri-Pacer, the PA-22-108 Colt, was released in 1960. The Colt was a two-seat training version of the airframe and had a 108 horsepower Lycoming O-235-C1.

The Piper PA-22-160 can cruise along at 134 miles per hour, and top out at 141 thanks to that Lycoming O-320 powerplant. There is space in the cockpit for two pilots and two passengers, though due to weight and balance, one passenger is more realistic. A fuel capacity of 36 US Gallons gives the PA-22 a range of 430 nautical miles, or 3:30 (with reserves.) Some Tri-Pacers have an optional 8-gallon fuel tank under the rear seat. The PA-22 is relatively small, only 20 feet / 6 inches long with a wingspan of 29 feet / 3 inches. As you’ll read about shortly, this makes the aircraft fun, but “interesting” to fly.

A total of 9,490 Piper PA-22 Tri-Pacers were built between 1950 and 1964. I have the distinct privilege and honor to fly a friend’s PA-22-160, N8140D. Located in Western New York, the aircraft is owned by a father and son team, Jay and Sean McKellar. The nicest people you’ll ever meet, they take pride in their work to get this airplane to its current airworthy status. Jay has been flying for years, and I will soon be teaching his son Sean to fly in the Tri-Pacer. I have been doing a “check-out” in the aircraft while giving Jay his flight review. N8140D was built in 1957 as a PA-22-160, MSN 22-5631. The McKellars acquired the plane in 2020 from the previous owner in Richfield, North Carolina. Much work has since been done on this Tri-Pacer to bring it back to life. The plane has been a labor of love, but the McKellars still have upgrades they’d like to make (including possible IFR flight upgrades!)

Enough talking, what’s it like to fly Piper’s ”Flying Milk Stool?” I am here to tell you, in one word, fun. Beginning with the startup, the Tri-Pacer cockpit is a bit tight for a guy who is 6 feet, 2 inches tall. The front seat moves back, but only an inch or two. Flying from the right seat, the CFI’s wheelhouse, provides a unique and challenging opportunity upon startup, as the master and starter switches are by the left-hand pilot’s left leg (as well as the fuel selector). So, in a teacher / early private pilot student scenario, start-up is a team effort. Once the engine is turning, you taxi. Taxiing in the PA-22 is different from any other plane I have handled before. Originally designed with a hand-brake, this aircraft has toe-brakes installed. The plane is “hot” on the ground, and you have to keep the rpm above 900-1000 to keep the engine happy (according to the manufacturer). So, you have to ride the brakes. It felt like I was a brand-new PPL student again.

The pre-takeoff flows are done, the checklist is verified, and the action plan is briefed; time to throttle up. Takeoff power is “balls to the wall” on the Tri-Pacer; 2700 rpm is a normal situation. The nose wheel likes to get squirrely on takeoff (and landing), so directional control is significant here. You watch for the gauges to be green, airspeed alive. Look for Vr on the dial, 55 mph, and you have to make the airplane fly. Unlike a C-172 or PA-28, you need to make the Tri-Pacer want to fly; it won’t take off and climb by itself. Once you’re off the ground, you must push the nose down to build airspeed. Look for 80 mph on the dial, then climb. At Vy, the best rate of climb, the PA-22 will settle at 84 mph. With a climb rate of 800 feet per minute, it feels like a little rocket ship!

You’ve reached your target altitude, and point the nose down to find your cruise speed. Set your power, and trim! Only trimming is a bit different here. The trim wheel is located over your head, on the ceiling of Piper’s 1957 “milk stool.” This takes some getting used to (and many mistakes of spinning the wheel in the wrong direction). The good news is that the wheel is marked to indicate where you should be turning it. After the first few hours, it becomes second nature, and you trim by instinct. As a right-handed CFI, this was initially a challenge for me. My left hand flows between the throttle (which, as a budding WWII fighter pilot, I prefer) and the trim crank. By the time my student earns his PPL in this bird, I’ll be ambidextrous.

The Tri-Pacer is happy in “high cruise” power settings at 24-2600 rpm, resulting in a speed of 120-135 mph and a fuel burn of around 9 gallons per hour. Maneuvers in N8140D are very enjoyable when properly trimmed (and that’s half the battle.) She’ll do steep turns with ease, although in any turn, you need to be very prudent with rudder inputs. A C-172 and a PA-28 have differential ailerons to help with adverse yaw. N8140D has a rudder and aileron interconnect, but it’s not a replacement for control input skills. You need to fly the airplane as if the rudder were keeping it afloat, rather than 100LL. This is a real benefit to students and experienced aviators alike. Your rudder skills get a workout! This PA-22 is part of Piper’s legacy of “short-wing” aircraft. I mentioned the short wingspan above, in the specifications paragraph. I found the “stubby” wings to be fun to fly with. Rolling into a turn felt like I was flying an F-16, when compared to a C-172 or C-182. Roll rate feels surprisingly quick compared to other single-engine GA training aircraft.

While on the subject of the wing, let’s talk about stalls. In the PA-22, both power-off and power-on stalls are relatively docile…if coordinated! Again, the short-wing will have a different set of behaviors in most phases of flight when compared to a Cessna 172 or similar. In a power-off stall, I go through my pre-maneuver flow, then set up for a pretend approach to land. At 65 miles per hour, I raise the nose and keep that ball centered. Vs0 approaches, 49 mph. Once you’re “there,” the Tri-Pacer won’t really “break.” You’ll feel the control “mush,” see the airspeed indicating 49 or less, see the altitude begin to drop, and then you just recover as you would in any other plane. There’s nothing flamboyant about it. Reduce the angle of attack, power up, first notch of flaps up, and stop the descent. Once descent is arrested and a positive rate of climb is established, the second notch of flaps comes up, and you climb back up to altitude.

Landing the Piper “milk stool” is a little different. As with any aircraft, the success of the landing depends on the setup. On downwind, you have to slow the Tri-Pacer to below Vfe (95 mph) to get half-flaps in (25°). On base, you’re looking for 70 mph and you put out full-flaps (40°.) Now, for the final approach. You’ll initially fly a normal descent angle of 3° at 65 mph, but the Tri-Pacer likes to sink, due to its short wings. As you get closer in, a flatter approach with power is more agreeable to the aircraft. On short final, use a twinge of power, usually 1500 rpm, just before flare. Once you touch down, power comes off immediately, and directional control must be maintained. Just as the PA-22 is squirrely on takeoff, the nosewheel likes to keep you guessing on landing roll-out.

You slow down, exit the runway, and clean the airplane up. Finally, you taxi back to the hangar, shut the “milk stool” down, and put the bird into the hangar for some well-deserved rest. Now you’ve done it! You’ve successfully flown a unique Piper-built aircraft. The Tri-Pacer may look unorthodox, but when it comes to flying, the PA-22 flies like an airplane should. That’s not to say the plane doesn’t have its quirks (as all do), but the looks of the airframe don’t detract from the overall performance. I am incredibly thankful and appreciative to the McKellars and N8140D for the opportunity to fly and teach in this aircraft. I am excited to see the journeys and flights we will take in the future. I’m also ready for whatever the next opportunity to fly a cool aircraft shows itself to be. You can be sure I’ll report on it!

Nice report. Also good to see an article based on a plane priced for the rest of us, in airworthy condition but without the usual $60k of avionic gadgets that somehow seems to required to have fun these days. Unmentioned, and important from an owner perspective, is that these old rag and tube Pipers are very rebuildable and repairable. With the average age of the light GA fleet now over 50 years, it’s a significant advantage over more “modern” designs.