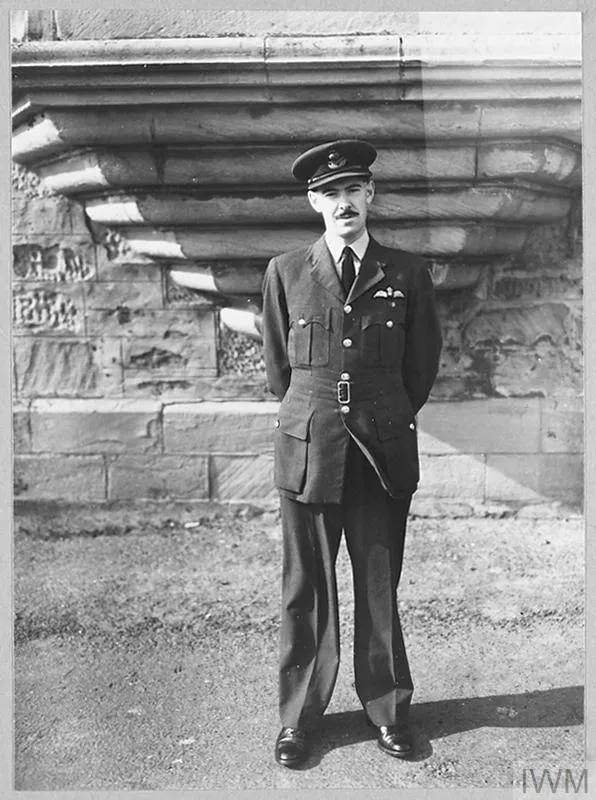

With it being 80 years now since the end of the Second World War, the loss of any WWII veteran represents a severance to our living links to the memory of the most destructive war in human history. Such is the case with Flight Lieutenant John Alexander “Jock” Cruickshank, VC, AE, who, at the age of 105, was the last living WWII recipient of the British Commonwealth’s highest award for valor, the Victoria Cross. Cruickshank’s family confirmed his passing on August 16 and announced that they will soon hold a private ceremony in his honor. In the meantime, we at Vintage Aviation News wish to celebrate Flight Lieutenant Cruickshank’s memory and do our part in ensuring that his story survives him.

Born on May 20, 1920, in Aberdeen, Scotland, John Cruickshank was a bank clerk at the Commercial Bank in Edinburgh when he enlisted in the Territorial Army (now the Army Reserve) on May 10, 1939, becoming part of the Royal Artillery. On June 30, 1941, he transferred to the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) and was sent to No. 1 Manning Depot in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Though he completed his initial flight training courses in Canada, he would complete his primary flight training at Naval Air Station Grosse Ile, Michigan, before earning his pilot’s wings at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida. Upon returning to the UK, he underwent Catalina Conversion Training at the Operational Training Unit in Invergordon, Scotland. After this, Flying Officer John Cruickshank was assigned to RAF Coastal Command’s No. 210 Squadron at RAF Sullom Voe in the Shetland Isles. He and his crew would regularly conduct long range maritime patrol, convoy escort and anti-submarine missions. On July 17, 1944, 24-year-old “Jock” Cruickshank was in command of Catalina Mk IV s/n JV928 and its eleven-man crew on a long-range patrol mission over the Norwegian Sea. That same day, the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet had launched an unsuccessful attempt to sink the German battleship Tirpitz with carrier-based aircraft. Five hours into the flight, Australian radar operator John Appleton sighted a contact on his scope. Upon coming to inspect the contact, it turned out to be the German U-boat U-361 (though wartime records originally listed the submarine as U-347). U-361 was on the surface, and her crew immediately manned their anti-aircraft guns and opened fire. Cruickshank’s crew attempted to drop their depth charges on the U-boat, but the depth charges failed to fall from the aircraft. Frustrated, Cruickshank climbed to 800 feet and turned the Catalina back towards the U-361, facing increased accuracy from the U-boat gunners. Catalina JV928 was hit multiple times, wounding half of the crew, including Cruickshank, who received 72 injuries from shrapnel, including two wounds to his lungs and ten to his legs. Meanwhile, navigator Flight Officer John “Dickie” Dickson was killed, co-pilot Flight Sergeant Jack Garnett was wounded in the hand, and John Appleton was hit in the head. Nevertheless, Cruickshank pressed his attack and managed to drop his depth charges around the U-361, which soon sank with all hands.

Despite destroying the submarine, it was only the beginning of John Cruickshank’s ordeal. Though losing a large amount of blood, Cruickshank remained at the controls until he was assured that the aircraft was under control, on course for base, and all necessary signals had been sent out. Only then did he consent to medical attention from the crew, with co-pilot Jack Garnett guiding the heavily damaged Catalina back to Sullom Voe. At the same time, Appleton, despite his head wound, carried Cruickshank to the plane’s galley to treat his captain’s wounds. Lapsing in and out of consciousness and in intense pain, Cruickshank still refused any morphine so as not to cloud his judgement should he need to return to the controls, which he insisted on, as well as asking about the crew’s status. Five and a half hours later, the crew of Catalina JV928 had reached RAF Sullom Voe, yet due to the excessive damage from the U-361, the Catalina was still filled with holes that would sink the aircraft if it landed in deep waters. Co-pilot Garnett did not have the experience to land the Catalina in the pre-dawn hours of the morning, which presented both sub-optimal light and sea conditions for a water landing. Though only able to breathe with immense difficulty, John Cruickshank insisted on returning to the cockpit, and with the aid of his crew, he did just that. Despite reaching the controls and his agonizing pain, Cruickshank insisted on orbiting Sullom Voe to wait for optimal conditions before landing at first light while the crew lightened the aircraft by throwing their guns, ammunition, and other loose items overboard.

With Cruickshank and Garnett at the controls, they landed in the waters off Sullom Voe and, with the last of his strength, Cruickshank taxied the Catalina to an area where the flying boat could be safely beached for future recovery. When RAF medical officer Patrick “Paddy” O’Connor boarded Catalina JV928, he gave John Cruickshank an immediate blood transfusion before taking him to the hospital, where O’Connor managed to save Cruickshank’s life, though his injuries were such that he would never again fly in command of a combat mission. On August 29, 1944, John Cruickshank was officially awarded the Victoria Cross. The final paragraph of his citation reads as follows: “By pressing home the second attack in his gravely wounded condition and continuing his exertions on the return journey with his strength failing all the time, he seriously prejudiced his chance of survival even if the aircraft safely reached its base. Throughout, he set an example of determination, fortitude, and devotion to duty in keeping with the highest traditions of the Service.”

Of the 181 servicemen of the British Commonwealth, only four were from RAF Coastal Command, and of those, only Cruickshank was not given the award posthumously. After retiring from the RAF in 1946, Cruickshank worked for over 30 years as a banker. He remained humble about his experiences in the 81 years since those extraordinary events and often spoke of the responsibilities that came with being a Victoria Cross recipient. “I hold this in trust for all those who flew with the command during the war. And of course, I also keep in mind all the members of my crew at that time who so magnificently carried out their duties.”

Since his retirement, John Cruickshank served as vice chairman of The Victoria Cross and George Cross Association, was interviewed about the events of July 17-18, 1944 (see this video HERE: FOR VALOUR JOHN CRUICKSHANK VC), made reunions with surviving members of his crew and of fellow WWII RAF Coastal Command veterans, and attended the dedication of the RAF Coastal Command Memorial inside the South Cloister of Westminster Abbey in 2004. In May 2024, Cruickshank was awarded the Air Efficiency Award. Later that year, the only Catalina flying in the UK, Catalina G-PBYA, better known to UK warbird enthusiasts as “Miss Pick Up,” made a flyover over Cruickshank’s home in Aberdeen before proceeding to Lerwick New Cemetery, where John Dickson and fellow Victoria Cross recipient and Catalina pilot David Hornell are buried next to each other.

Crew of Catalina Mk IV RAF s/n JV928, July 17-18, 1944 F/O John Cruickshank (captain) Flt Sgt Jack Garnett (second pilot) Sgt Ian Fidler (third pilot; brought for training) F/O J.C. “Dickie” Dickson (navigator/bomb aimer) Flt Sgt S.B. “Paddy” Harbison (flight engineer) W/O W.C. Jenkins (wireless operator) Flt Sgt H. Gershenson (wireless operator) Flt Sgt John Appleton (gunner) Sgt R.S.C. Procter (gunner) Flt Sgt A.I. Cretan (rigger/flight mechanic)

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.

Brave men all. R.I.P.. Lest we forget.