By John M Curatola LtCol USMC (Ret), PhD, F.RHistS Samuel Zemurray Stone Senior Historian, Institute for the Study of War and Democracy, National World War II Museum

On 21 June 2025, seven B-2 “Spirit” bombers departed their home base at Whiteman AFB in Nob Noster, Missouri, and flew 18 hours to strike Iran’s Fordow and Natanz nuclear facilities. The mission was labeled Operation Midnight Hammer. Flying with fourteen 3,000-pound GBU-57/B Massive Ordnance Penetrator bombs in their bomb bays, the crews required dozens of mid-air refueling sessions. Traveling some 14,000 miles made this one of the longest strategic air strikes in history. While battle damage assessments are still underway, the execution of the strike was a marvel of strategic reach and global strike capability. However, this attack was just the latest in the history of long-range strategic bombing.

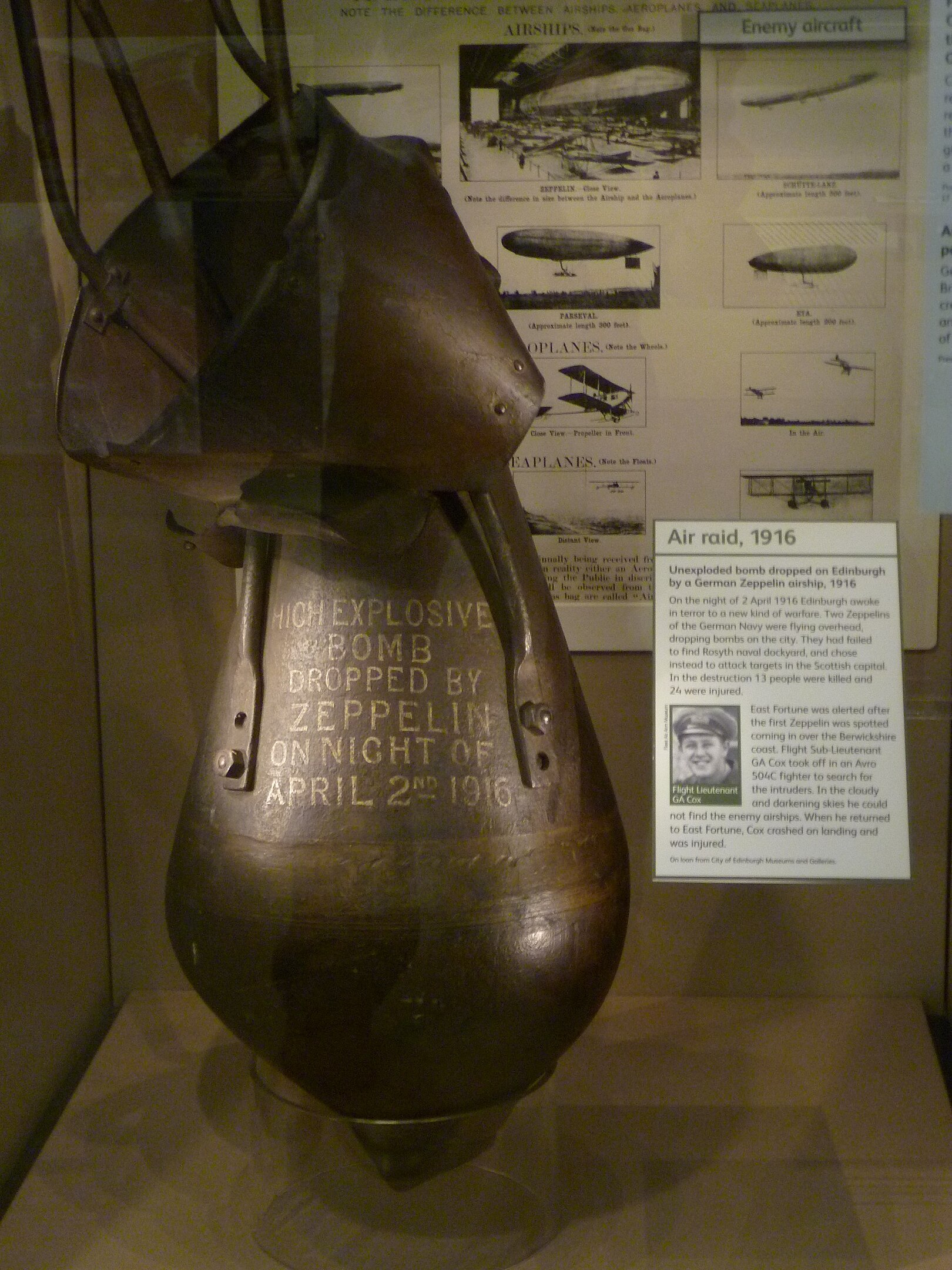

Strategic bombing is almost as old as military aviation, with raids occurring as early as 1914, including Zeppelin raids over England in 1915. As World War I ended, German Gotha raids became a common occurrence over British cities. Other conflicts soon followed, embracing the promise of striking an enemy’s strategic centers of gravity as a means to secure victory. While bombing campaigns are often controversial and have experienced varying degrees of success, one impressive factor is the ever-increasing distances bomber crews flew to reach their targets. As aviation technology grew during the last century, so too did strategic bombing’s worldwide reach and ability to strike at the far reaches of the globe.

In World War II, the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) and Royal Air Force (RAF) executed the Combined Bomber Offensive over occupied Europe. In this round-the-clock effort, aircrews regularly flew hundreds of miles hitting Nazi infrastructure and military targets. However, on August 17, 1943, 8th Air Force crews from the 3rd Bomb Division under Colonel Curtis LeMay flew one of the longest missions of the European campaign. One hundred forty-six B-17 “Flying Fortresses” with long-range fuel tanks departed bases in East Anglia and headed toward the town of Regensburg, Germany. Striking the nearby Messerschmitt aircraft factory, the bombers suffered at the hands of German air defenses, losing approximately 18 percent of the force. However, the crews did not head home. Instead, the surviving planes made an abrupt turn heading south toward North Africa. After flying over the Alps and the Mediterranean, they finally approached the Tunisian coast. Covering some 1,500 miles and having been in the air for 11 hours, the Fortresses’ engines were running on fumes. With dusk approaching, crews looked for unfamiliar air bases, hoping to avoid ditching in a cold, barren desert in the dark. Starting at 1758, just as the sun was setting, what was left of the formation put down near the Algerian towns of Bone and Telergma. However, the promised logistics support in North Africa failed to materialize, with crews having to salvage or cannibalize their airframes. With only sixty airworthy planes, they headed back to England on 24 August while bombing a German airfield at Bordeaux, France en route. Given the resulting losses and difficulties, such missions were avoided in the future. While shuttle missions to Soviet airfields occurred later in the war, they too proved problematic and were soon halted. Regardless of the difficulties, LeMay and the crews of the 3rd Division deserve credit for this long-range sortie over Western Europe and the Mediterranean.

With the introduction of the B-29 “Superfortress” bomber, the USAAF had a new and powerful weapon in the war against Japan. With a combat range of 3,200 miles, the B-29 was an engineering marvel with four powerful new R-3350 engines producing 2,200 horsepower. Having flush rivets, butt-joined sections, a pressurized cabin, and remote-controlled armament, the new plane was a significant leap in aviation technology. However, there is an old Air Force adage claiming, “Never fly the ‘A’ model of anything…” Such a warning certainly applied to the new B-29. First used by 20th Bomber Command in the China-Burma-India Theater in spring 1944, technical and logistical problems soon saw the effort shut down. Later that fall, 21st Bomber Command, flying out of the Mariana Islands chain, began conducting raids over the Japanese home islands. However, the new bomber’s mechanical maladies continued, with crews also facing challenging weather patterns. Despite these obstacles, crews still conducted missions covering over 3,000 miles, lasting 10–12 hours, while flying near the edge of the plane’s range. Although combat over the Japanese home islands may have taken only a few tense minutes, most of these flights were over the vast Pacific Ocean, where the chances of being lost at sea were a constant and real possibility. Eventually, 21st Bomber Command, now under Lieutenant General LeMay, addressed many of the bomber’s technical issues and switched to low-level area attacks. While the airframe matured along with developing more proficient and experienced crews, covering the trek between the Mariana Islands and Japan remained an aeronautical challenge.

In April 1982, an Argentine military junta invaded the British-owned Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic. Unwilling to cede their claim to this remote archipelago, Royal Navy and Marine forces sailed south to liberate the occupied islands. Supporting this endeavor was RAF strategic airpower conducting a series of long-range strikes against Argentinian forces. To conduct these raids on the occupied islands, the RAF employed its soon-to-be-retired Avro Vulcan bombers. Referred to as “Black Buck” missions, this set of seven raids targeted the Argentinian-held airfield at Port Stanley and its early warning radars. Conducting these strikes, the Vulcans carried either twenty-one 1,000 lb bombs or a complement of Shrike anti-radiation missiles. Flying from Wideawake Airfield on the tiny mid-Atlantic island of Ascension, the Vulcans traveled 8,000 miles per mission. To traverse this distance, Vulcan crews required substantial aerial refueling help from a fleet of Avro Victor aircraft working in coordinated sets. Inbound to its target, a single Vulcan required seven refueling sessions, with an additional one on the return trek. However, to support a single Vulcan sortie required the assistance of eleven Victors, many passing fuel to each other. Such an operation over this great expanse required a highly complex and intricate juggling of assets. Of the seven missions scheduled, two were canceled by weather or mechanical issues. The five “Black Bucks” making it to the Falklands had varying degrees of success, with the Port Stanley runway receiving only minor damage while partially disabling Argentine radars. Despite these results, given the complexity and difficulty of the operation, these strikes were an amazing feat of strategic reach.

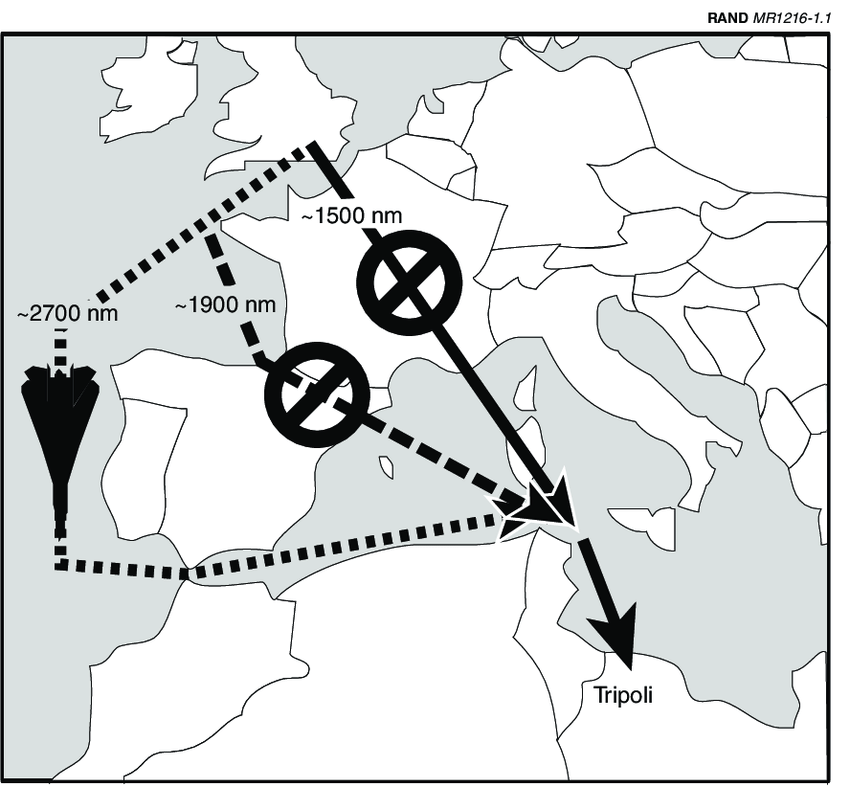

As strategic bomber reach grew, a few years after the RAF’s Black Buck missions, U.S. Air Force (USAF) F-111 fighter-bombers conducted their own long-range combat strike. Dubbed “Operation El Dorado Canyon,” the mission targeted Libyan strongman Muammar Qaddafi. Allowing safe haven for extremist groups, Qaddafi provided state sponsorship for terrorist activities and housed training camps in the North African country. Intent on destroying these camps and sending a message to the rogue leader, USAF and Navy aircraft conducted a joint attack on April 14, 1986. The strike included the USAF’s 48th Tactical Fighter Wing stationed at Lakenheath in the U.K., electronic support from five EF-111s of the 42nd Electronic Combat Squadron at RAF Upper Heyford, and carrier aviation support from the U.S. 6th Fleet’s USS America and Coral Sea. However, some European countries denied overflight rights to the U.K.-based jets, causing them to fly around the Iberian Peninsula and then into the Mediterranean via the Strait of Gibraltar.

Lacking diplomatic clearances, the initial strike package of 24 U.K.-based F-111s had to take the circuitous route, with the mission lasting 13 hours. Covering a round trip of over 6,400 miles, the F-111s conducted at least eight aerial refuelings, requiring 19 KC-10 “Extenders” and 10 KC-135 “Stratotankers.” Carrying a combination of four GBU-10 2,000-pound laser-guided bombs or nine Mark 82 “Snakeye” 500-pounders, the F-111s arrived at low level around midnight over the target area. The raid hit the base at Bab al-Aziziya near the Libyan leader’s home in Tripoli, the Mitiga International Airport, and training camps at Murat Sidi Bilal. Only four F-111s successfully dropped their weapons, while others encountered mechanical problems precluding a precision drop, with some missing their targets. During the raid, one F-111 and its crew went missing, suspected to have been hit by a surface-to-air missile. The strike killed 37 people and wounded approximately 100; however, it visibly shook Gaddafi. While the raid was controversial, it provided an early glimpse into the USAF’s emerging long-range fighter strike capability.

As Operation Desert Shield transitioned to Desert Storm, coalition airpower began shaping the operational environment. This combined effort sought the removal of Iraqi forces after their invasion of their smaller Kuwaiti neighbor in summer 1990. However, one of the initial airstrikes came not from tactical aircraft in the area of operations, but from strategic bombers launched 14,000 miles away. Before the ground campaign began liberating Kuwait from Iraqi forces, the Allied air component targeted select elements of the Iraqi leadership, command and control centers, and specific military formations. Spearheading this effort were seven B-52G “Stratofortresses” from the 596th Bomb Squadron stationed at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. Classified as Operation Senior Surprise (and comically referred to as Operation Secret Squirrel by airmen), the seven bombers carried thirty-five Air Ground Missile (AGM)-86C Conventional Air-Launched Cruise Missiles (ALCMs). The weapons were armed with 1,000 lb warheads guided by a Global Positioning System, aimed at Iraqi power plants and communications centers. The bombers launched from a soggy runway at 0636 on the morning of 16 January 1991 and climbed into a cloudy sky. Refueling over the Atlantic and again over the Mediterranean, the Stratofortresses made their way to Saudi Arabian airspace. With H-Hour set for 0300 on 17 January, the fleet of bombers arrived at their launch points within seconds of their scheduled appearance. Once on station, crews began arming and then launching their weapons. While four AGMs failed to salvo, the remainder found their targets, crippling Iraqi defensive capabilities. Fifteen hours after departing their home station, the crews headed west, looking for their next refueling rendezvous. Perhaps the most perilous part of the mission was the flight home. Fighting both strong headwinds and adverse weather, some planes needed emergency refueling sorties to make it home. After thirty-five hours in the air, the bombers finally returned to Barksdale. Given the distances flown, the B-52 crews set a new world record for the longest bombing mission ever conducted.

This article superbly captures the evolution of aviation strategy, weaving in remarkable stories from WWI airships to the modern B-2 mission. The writing is both rich in detail and exhilarating, bringing the sheer scope of long-range operations into sharp focus.