By Dan Rivera

The Sky Was Never the Limit

During a time when the United States Armed Forces were racially segregated and African Americans were openly deemed unfit for combat roles by prevailing racist doctrines, a group of determined Black men took to the skies and changed history. These aviators, who became famously known as the Tuskegee Airmen or the Red Tails, not only broke the color barrier in military aviation but also shattered myths of inferiority with every mission they flew, every bomber they protected, and every enemy aircraft they downed. Their service and sacrifice paved the way for the eventual integration of the U.S. military and served as a beacon of hope for civil rights reform in America.

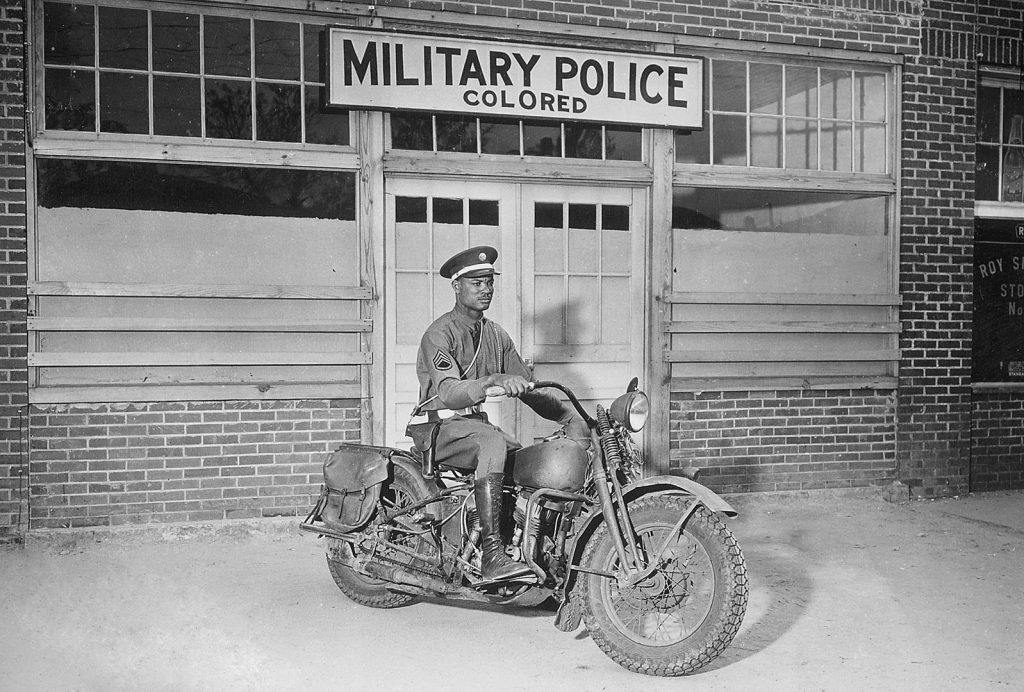

The Road to Tuskegee – A Nation Divided

Before there were planes, there was prejudice. In the years leading up to World War II, the U.S. military, like much of the country, operated under strict segregation. African Americans were largely relegated to service roles. Despite their patriotism and desire to serve, Black Americans were denied opportunities in combat arms, especially in aviation. The prevailing belief was that Black men lacked the intelligence, courage, and discipline to be effective pilots. Yet mounting pressure from civil rights organizations, Black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier, and influential figures such as A. Philip Randolph and Walter White of the NAACP forced the Roosevelt administration to reconsider. In 1941, as global war loomed and America’s military began expanding rapidly, the War Department authorized an experimental aviation training program for African Americans at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. This program would not only test the limits of aircraft—it would test the soul of a nation.

Building an Air Force at Tuskegee

Tuskegee Institute, founded by Booker T. Washington, was chosen for its aviation facilities and academic rigor. The program included both flight training and ground instruction. The Army Air Corps established the Tuskegee Army Air Field, and the first class of five cadets began training in July 1941. The training was grueling. Cadets faced not only the normal rigors of becoming military aviators but also the additional pressure of proving their race’s capabilities to a skeptical military hierarchy. One of the earliest pioneers was Benjamin O. Davis Jr., a West Point graduate and the only Black officer in his class. He would later become the commanding officer of the Tuskegee Airmen and rise to the rank of General. By the end of the program, more than 1,000 African American pilots and thousands more support personnel—mechanics, navigators, bombardiers, radio operators—were trained. They formed the core of what would become the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group.

The 99th Pursuit Squadron Takes Flight

The 99th Pursuit Squadron, later renamed the 99th Fighter Squadron, was the first of the Tuskegee squadrons to be activated. It deployed to North Africa in April 1943 under the command of Lt. Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. They were assigned to the 12th Air Force, flying Curtiss P-40 Warhawks in support of Allied ground forces. The 99th flew missions over Tunisia, Sicily, and later Italy. Though initially limited in their role, they quickly earned a reputation for tenacity and professionalism. In June 1943, they participated in the invasion of Pantelleria, an island fortress in the Mediterranean. The island was bombed into submission without a single Allied casualty, partly thanks to the air cover provided by the 99th. Although their performance was questioned by some racist commanders, official evaluations proved their effectiveness. The 99th proved that African American pilots were not only capable—they were exceptional.

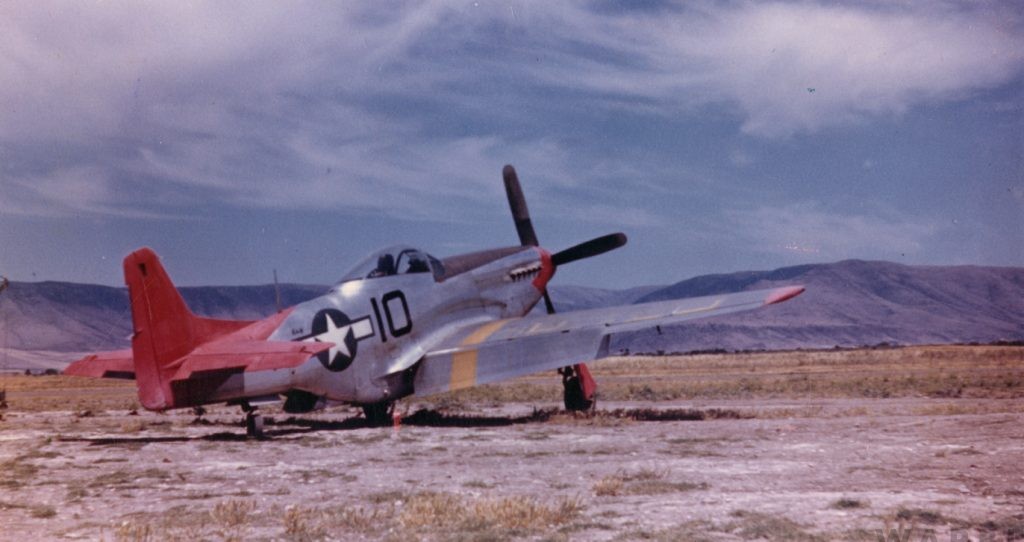

Formation of the 332nd Fighter Group

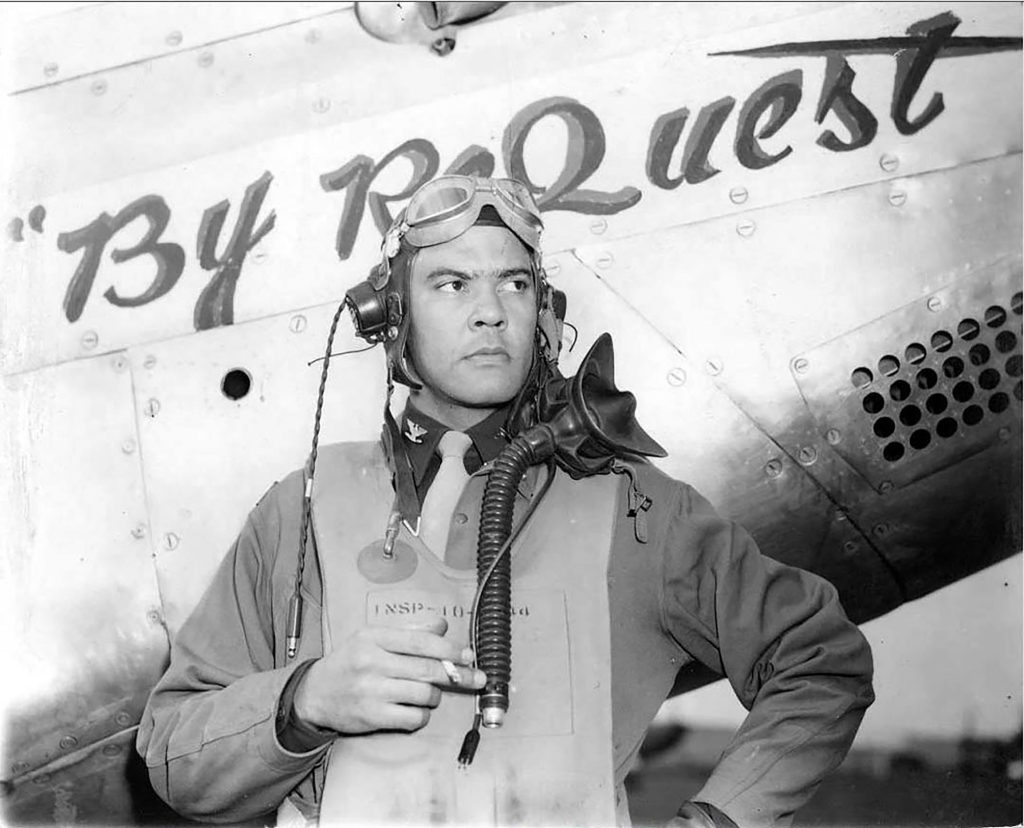

In early 1944, the Army Air Forces consolidated several Tuskegee squadrons under the newly formed 332nd Fighter Group, which included the 100th, 301st, and 302nd Fighter Squadrons, with the 99th Fighter Squadron later attached as well. The group was based at Ramitelli Airfield in Italy and transitioned to flying P-47 Thunderbolts, and later, the iconic P-51 Mustangs. These aircraft bore a distinguishing mark: their tails were painted bright red. Thus, the legend of the Red Tails was born. Under Davis’s leadership, the 332nd began flying bomber escort missions—some of the most dangerous and vital assignments of the air war.

Escorting Bombers, Defying Odds

One of the most critical jobs in the U.S. Army Air Forces was protecting bomber formations from enemy fighters. German Luftwaffe units like the JG 27 and JG 53 inflicted heavy losses on American bombers flying deep into enemy territory. The Tuskegee Airmen were assigned to escort B-17 and B-24 bombers on missions into Germany, Austria, and the Balkans. Their performance was extraordinary. Unlike some other units, the Red Tails stuck close to the bombers rather than chasing enemy aircraft for personal glory. As a result, they developed a strong reputation among bomber crews for reliability and effectiveness.

They flew more than 15,000 sorties, escorted over 200 long-range bombing missions, and were credited with shooting down 112 enemy aircraft in aerial combat. They destroyed over 950 enemy rail cars, vehicles, and other ground targets. Fewer bombers were lost to enemy fighters under their escort compared to other units. One of the most storied missions occurred on March 24, 1945, during a mission to escort bombers to Berlin. The Tuskegee Airmen encountered a group of German Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighters—some of the most advanced aircraft of the war. Despite being outmatched in speed, the Red Tails managed to shoot down three of these jets, marking one of the rare but significant instances where propeller-driven aircraft successfully engaged and shot down jet fighters in combat.

The 477th Bombardment Group and the Freeman Field Mutiny

While the 332nd gained glory in the skies over Europe, another chapter of the Tuskegee legacy was unfolding stateside. The 477th Bombardment Group was formed in 1944 as a unit of Black bomber crews. Despite being combat-ready, systemic racism kept them grounded. At Freeman Field, Indiana, Black officers were denied access to the base’s segregated officers’ club, violating Army regulations. In protest, 101 officers participated in what became known as the Freeman Field Mutiny. Though arrested, their actions led to increased scrutiny of segregation in the military and were later seen as a pivotal moment in the push toward integration.

Honors, Legacy, and Integration

The legacy of the Tuskegee Airmen is not just about kills or bombers escorted—it’s about the transformation they forced within the military and the country. They proved that ability, not race, determined worth. They earned Distinguished Unit Citations, Silver Stars, Bronze Stars, Distinguished Flying Crosses, and Air Medals. In 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981, desegregating the U.S. Armed Forces. It was a direct result of the courage and professionalism of units like the Tuskegee Airmen.

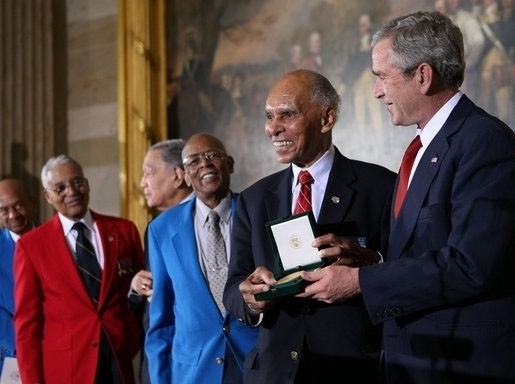

Postwar Contributions and Modern Recognition

Many Tuskegee Airmen went on to prominent careers in aviation, business, and public service. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. became the first Black general in the U.S. Air Force. Others became airline pilots, educators, and community leaders. In 2007, the surviving members of the Tuskegee Airmen were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President George W. Bush. In 2009, they were honored guests at President Barack Obama’s inauguration—a testament to the barrier-breaking legacy they helped build. Their legacy continues today, not only in the enduring symbol of the Red Tails but in the generations of aviators and leaders they inspired. Their courage in the face of injustice transformed both military history and the broader fight for civil rights in America.