On June 22, 2025, seven Northrop B-2A Spirit stealth bombers of the 509th Bomb Wing (BW) returned to Whiteman AFB, Missouri, concluding their role in Operation Midnight Hammer. During this operation, they employed fourteen 30,000-pound GBU-57/B Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP) bombs against Iranian nuclear facilities at Fordow and Natanz. According to the Pentagon, the 36-hour round-robin mission marked the largest B-2 strike in history and the second longest in a quarter-century. The legacy of the B-2, however, stretches back nearly a century.

509th Bomb Wing

509th Bomb Wing

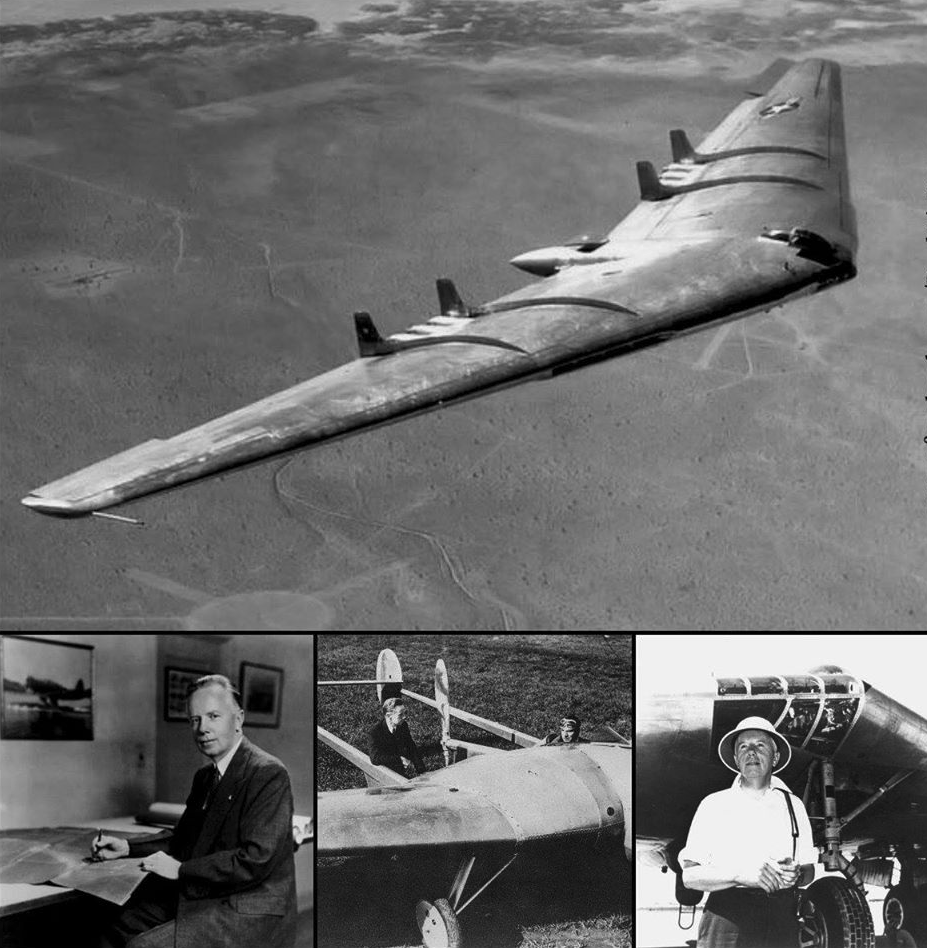

Born in Newark, New Jersey, on November 10, 1895, John Knudsen “Jack” Northrop worked on the design of the Douglas World Cruiser, served as chief engineer on the Lockheed Vega, and led his company in producing aircraft such as the P-61 Black Widow and F-89 Scorpion. More than anything else, however, Northrop—both the man and the company—is synonymous with the flying wing concept. The idea was conceived while Northrop was at Douglas in the early 1920s; he believed it was the most aerodynamically efficient aircraft configuration.

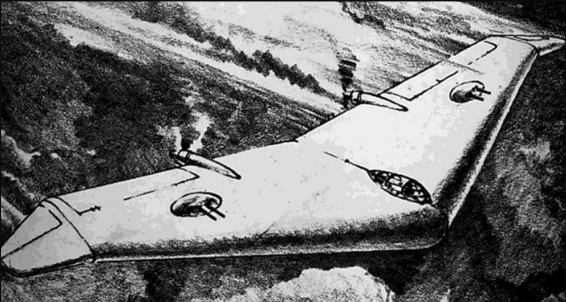

His first step toward realizing this vision was the experimental Avion Model I, which first flew in 1929. Though not a true flying wing—it featured a forked tail—it laid the groundwork for future designs. In 1939, while working at his second company, Northrop Corporation, he began developing the N-1, his first pure flying wing. This design was a response to the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) XC-219 specification for a high-altitude medium bomber. Though the N-1 never progressed beyond the drawing board, the company did build a flying mockup, designated N-1M.

The N-1M featured a tubular steel blended fuselage, with wings made of laminated wood. It had a swept wing with drooped wingtips, a small bubble canopy, and twin 65-hp Lycoming O-145 four-cylinder engines mounted in a buried pusher configuration. Chief test pilot Vance Breese performed its first brief flight on July 3, 1940, but the aircraft proved overweight and underpowered. The Lycomings were soon replaced with a pair of 120-hp Franklin 6AC264F2 engines.

The N-1M’s flight test program lasted just over 30 flights but demonstrated the concept’s viability. On October 30, 1941, Northrop received a contract to develop what would become the B-35 Flying Wing. While the full-scale aircraft—with a wingspan of 172 feet—was under construction, the company built four one-third scale test aircraft designated N-9M. Like the N-1M, the N-9Ms featured a tubular center section and laminated wood wings. All but one were powered by twin 290-hp Menasco C6S-1 inverted six-cylinder engines.

The first N-9M made its maiden flight on December 27, 1942, with test pilot John Myers at the controls. Flight testing continued through 1943, but following the cancellation of the B-35 program, three N-9Ms were scrapped. The final example, the N-9MB, survived and was restored to airworthy condition at the Planes of Fame Museum in Chino, California, where it flew for decades before tragically crashing in 2019.

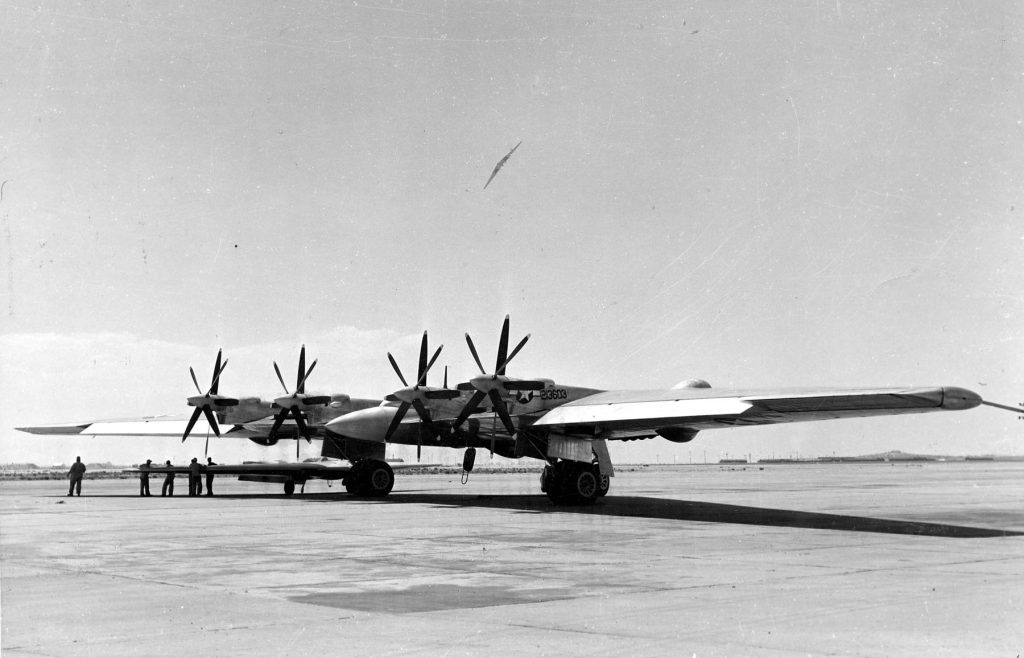

In December 1941, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) awarded prototype contracts to Northrop and Consolidated for a heavy bomber capable of delivering a 10,000-pound bomb load on a 10,000-mile round-trip mission. This requirement assumed Britain might fall to Nazi Germany, necessitating strikes on the Reich from North America. The aircraft also needed to cruise at 275 mph, reach a maximum speed of 450 mph, and operate at 45,000 feet. Development was slow, and the first XB-35 (#42-13603) did not fly until after World War II, making a 45-minute flight from Hawthorne to Muroc Army Airfield on June 25, 1946.

The aircraft was quickly plagued by severe vibration issues in the drive system linking its Pratt & Whitney R-4360 radials to Hamilton-Standard three-bladed contra-rotating propellers. The issue grew serious enough that Northrop grounded the aircraft, prompting meetings with Pratt & Whitney, Hamilton-Standard, and the USAAF. On February 17, 1947—eight months after its first flight—it was decided to abandon the contra-rotating props in favor of conventional four-blade units. However, the first flight with the new setup didn’t occur until February 12, 1948.

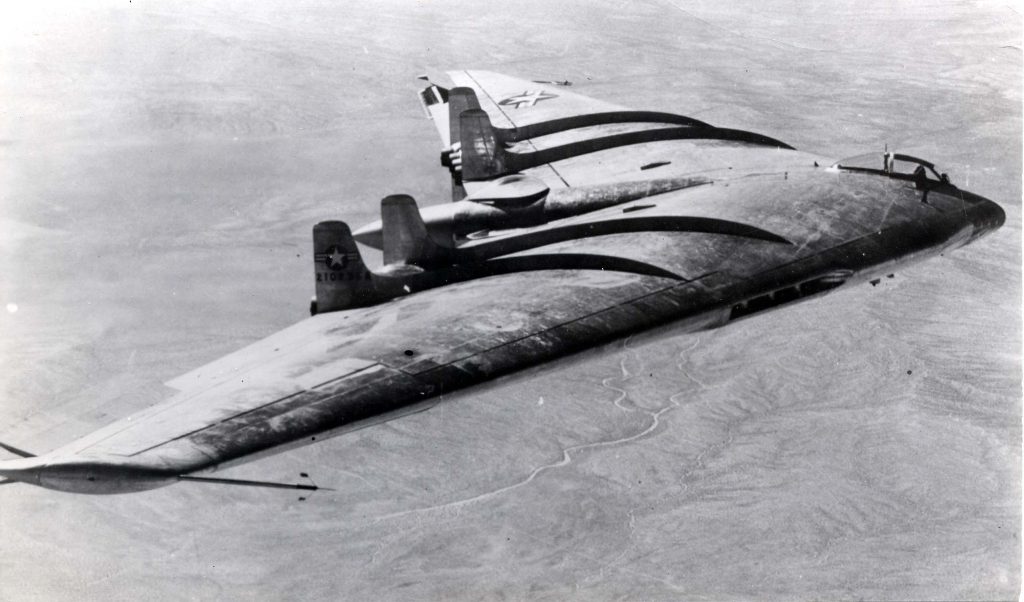

By the late 1940s, the Flying Wing appeared doomed. On June 5, 1948, YB-49 #2 crashed, killing all three crew members. In January 1949, Northrop was ordered to stop work on the RB-49 variant, though the YRB-49A continued. In May, the planned conversion of B-35Bs to jet power was canceled. Between July 1949 and March 1950, a dozen B-35s were scrapped, and YB-49 #1 was lost in a taxiing accident.

A brief moment of hope came when YRB-49A (#42-102376) flew on May 4, 1950, but it too was scrapped three years later. By then, Jack Northrop had not only left the company he founded but had also withdrawn from the aviation industry entirely. Yet the YB-49’s continued testing proved useful. In February 1981, nearly 30 years after the last flying wing was dismantled, Northrop was briefed on the development of a classified stealth bomber—the future B-2 Spirit. Reportedly, he said, “Now I know why God has kept me alive for the past 25 years.” He died just days later.

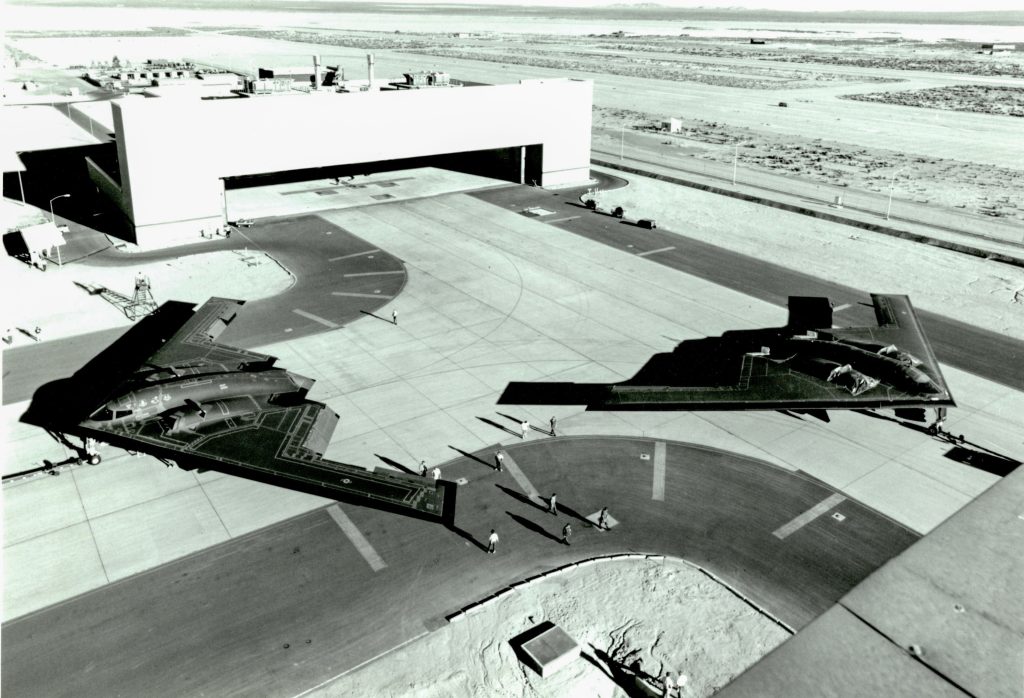

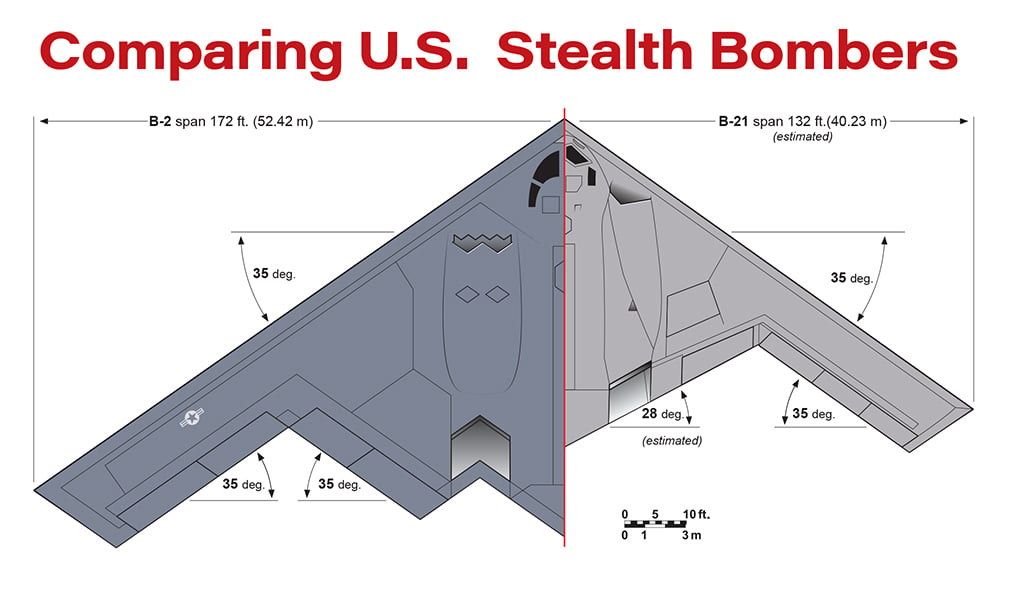

The Advanced Technology Bomber (ATB) program began in 1979 as a black project under the codename Aurora. On October 20, 1981, it was announced that Northrop had won the contract. The B-2 was officially unveiled at Northrop’s Plant 42 in Palmdale, California, on November 22, 1988. During the ceremony, Secretary of the Air Force Edward C. “Pete” Aldridge, Jr., declared, “This is a landmark event for our nation’s strategic deterrent posture.” He noted that the B-2’s wingspan—172 feet—matched that of the earlier B-35 and B-49.

After extensive development and testing, B-2 USAF #82-1066 (AV-1) took to the sky on July 17, 1989. Air Force Chief B-2 Test Pilot Colonel Rick Couch recalled, “It came off the ground so smooth we hardly knew we had.” This first flight was a ferry mission from Palmdale to Edwards AFB, where rigorous flight testing commenced. In the mid-1980s, at the height of the Cold War, 132 B-2s were planned. But on April 26, 1990, after the fall of the Soviet Union, Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney proposed reducing that number to 75. In 1992, President George H. W. Bush further cut procurement to just 20 aircraft. Each B-2 ultimately cost $566 million. Given the end of the Cold War and the decisive victory in Desert Storm, some questioned whether the B-2 would ever prove its worth. That question would be answered before the century’s end.

The B-2 made its combat debut in Operation Allied Force (1999), which also saw the first operational use of the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM)—a kit that turns unguided bombs into precision weapons. In the first eight weeks, B-2s dropped 11% of the bombs, destroying 33% of Yugoslav targets. These missions lasted 30 hours and were flown non-stop from Whiteman AFB, demonstrating the bomber’s global reach.

Following the September 11 attacks, the B-2 remained on the front lines. In Operation Enduring Freedom, it flew long-range missions to strike Taliban targets in Afghanistan. During Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003, B-2s flew from Whiteman and forward bases at Diego Garcia, Andersen AFB in Guam, and RAF Fairford in the UK. In March 2011, Spirits were the first to strike targets in Libya during Operation Odyssey Dawn—flown once again from Whiteman. These missions echoed Gen. Bernard Randolph’s 1989 comments recalling Operation El Dorado Canyon in 1986, when F-111Fs flew 3,500 miles from the UK to strike Libya after France denied overflight. Randolph suggested, “…three or four B-2s flying from the United States could have done it… with complete surprise.” The B-2 could have reduced the operation to four bombers and five tankers, risking only eight lives.

During a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing on February 22, 1990, Senator Albert Gore asked former Secretary of Defense Frank Carlucci, “Can you conceive the U.S. risking a $500-million-dollar airplane on a raid on Tripoli?” Carlucci replied, “Yes, sir. I would have used it. If it is a question of trading off lives against machinery, I’ll go for the lives every day.” Throughout the 2010s and early 2020s, B-2s continued striking targets in Iraq, including a record 44.3-hour mission in September 2013, and returned to Libya. In October 2024, perhaps as a show of force toward Iran, B-2s struck Houthi underground weapon facilities in Yemen. Then came Operation Midnight Hammer.

Until then, the B-2 had rarely been tested in a heavily contested airspace. Midnight Hammer involved over 125 aircraft, including seven B-2s from Whiteman and two dozen submarine-launched Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAMs). For the first time, the Spirits employed fourteen GBU-57/B MOPs against deeply buried nuclear sites at Fordow and Natanz, while TLAMs hit a third site at Isfahan.

509th Bomb Wing

This was the largest B-2 mission ever and the second-longest in the aircraft’s history. The global strike power it demonstrated fulfilled Jack Northrop’s original vision of what the XB-35 could have been during the early days of World War II. His legacy will not end with the B-2’s retirement.

In July 2014, the Air Force issued a request for proposals for the Long-Range Strike Bomber (LRS-B), awarding the contract to Northrop Grumman in October 2015. At the 2016 Air Warfare Symposium, the new aircraft was officially designated the B-21. On September 19, 2016, Richard E. Cole, the last surviving Doolittle Raider, announced it would be named “Raider” in honor of the 80 men who flew the April 18, 1942 mission over Japan.

Like the B-2 before it, the Raider was unveiled at Plant 42 in Palmdale on December 2, 2022, and made its maiden flight on November 10, 2023. As of this writing, three B-21s are undergoing testing with the 412th Test Wing B-21 Combined Test Force at Edwards AFB, California.

Although initially envisioned as a long-range strike platform, the B-21—humanity’s first sixth-generation combat aircraft—will also serve as a networked intelligence collector and battle manager, akin to the F-35. While its full role remains to be seen, the Raider is set to replace both the B-1 and B-2 fleets sometime in the 2050s, extending Jack Northrop’s legacy into the 22nd century—more than 160 years after he first envisioned the flying wing.

Stephen “Chappie” Chapis's passion for aviation began in 1975 at Easton-Newnam Airport. Growing up building models and reading aviation magazines, he attended Oshkosh '82 and took his first aerobatic ride in 1987. His photography career began in 1990, leading to nearly 140 articles for Warbird Digest and other aviation magazines. His book, "ALLIED JET KILLERS OF WORLD WAR 2," was published in 2017.

Stephen has been an EMT for 23 years and served 21 years in the DC Air National Guard. He credits his success to his wife, Germaine.