In 2013, back when Vintage Aviation News was still Warbirds News, we published a short article about the efforts to restore a Donnet-Lévêque Type A, a rare French pre-WWI flying boat for the Swedish Air Force Museum (Flygvapenmuseum). Later that year, in fact, the museum completed the restoration of this rare aircraft, and it has since been on display inside the museum at Malmen Airbase near Linköping. Given the airplane’s rich history and its status as one of the oldest surviving military airplanes of any nation, its story deserves a wider audience. The story of the Donnet-Lévêque begins with François Denhaut, a French cyclist turned pilot and aircraft builder. Although it would be fellow Frenchman Henri Fabre who would become the first to build and fly a seaplane in 1910, Denhaut is credited with having been the first to design, build, and fly a “flying boat”, that is, a seaplane whose hull rests on the water, as opposed to Fabre’s Hydroavion, which was the first floatplane.

Denhaut built this aircraft with the assistance of Swiss engineer and financier Jérôme Donnet, who had prior success in the automotive industry. Denhaut’s design from 1912 would soon become a worldwide standard in the construction of flying boats, featuring a cockpit in the bow of the hull, a biplane design with an engine mounted between the wings and supported above the hull, small pontoons on the wingtips to add stability in the water, and a set of horizontal and vertical stabilizers at the tail. As Denhaut finalized his initial design, however, he had trouble taking off from the surface of the River Seine, where he was conducting his water and flight trials. Seeking technical assistance, Denhaut visited with a naval engineer named Robert Duhamel, who advised him that he should add a flat bottom and a step in the hull forward of the center of gravity in order to break the water’s suction from the hull of the flying boat and allow the craft to take to the air. Denhaut took this advice, but considering he had progressed too far in construction and did not have the means to completely rebuild the hull, he chose to apply that theory to the next design.

On March 10, 1912, François Denhaut made the first flight of a flying boat from Port-Aviation in Essonne, not far from where Paris-Orly Airport stands today. Though it was a successful take off, when Denhaut attempted to land on the Seine, he misjudged his approach and the aircraft ended up flipping over onto its back. Fortunately for Denhaut, he was unharmed by this incident and was determined to incorporate Duhamel’s recommendations into the next aircraft.

Though financial issues prevented Donnet from helping Denhaut reconstruct his flying boat, Denhaut had already become the chief pilot for a flight school founded by aircraft manufacturer Pierce Levasseur, whose workers helped Denhaut build this new flying boat. The new design performed much better than the first one, and this attracted the attention of Henri Lévêque, an automobile engine manufacturer who had witnessed Denhaut’s test flights above the Seine. Soon, word in the growing aviation community spread of Denhaut’s flying boat, with English pilot and aircraft builder Thomas Sopwith flying an example of one of Denhaut’s machines and became an advocate for the adoption of flying boat designs in Britain, while in the United States, Glenn Curtiss came up with his own flying boat, the Model F around the same time that Denhaut had developed his designs independently of Curtiss.

By April 1912, Henri Lévêque and Jérôme Donnet joined forces to create the Donnet-Lévêque Hydroaeroplane Company. While Denhaut struck out and worked for other French aviation pioneers such as Morane-Saulnier, Donnet-Lévêque hired a French Navy lieutenant, Jean Louis Conneau (better known as André Beaumont), and Louis Schreck developed Denhaut’s initial design as the Donnet-Lévêque Type A, powered by a single 50 hp Gnome Omega seven-cylinder rotary engine. Soon, the Type A attracted the attention of the British Royal Navy, and by 1913, Beaumont and Schreck established the Franco-British Aviation (FBA) Company in London to build examples of the Donnet-Lévêque Type A in Britain, with the aircraft becoming the FBA Type A. The production models of the Model A were now equipped with the 80 hp Gnome Monosoupape 7 Type A rotary engine. Besides the Royal Navy, the FBA Type A and its succeeding designs (the Type B and Type C) attracted further interest from across the world. Indeed, the Austro-Hungarian and Danish navies both adopted the Type A before the outbreak of the First World War, and during the war, the FBA flying boats were used for maritime reconnaissance and flight training, and were operated by the Brazilian, British, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Russian navies. The aircraft developed from the original Donnet-Lévêque flying boat also encouraged the development of indigenous flying boat designs, and by the end of WWI, including others in France by François Denhaut, who worked with Jérôme Donnet to create the Donnet-Denhaut series of flying boats used by the French, American, and Portuguese navies in WWI.

By the end of the Great War, the flying boat was now a proven concept, and the years after the war would see the development of flying boats that could fly further, faster, and higher than the Donnet-Lévêque Type A ever was. The Franco-British Aviation Company continued to build new flying boat designs well into the 1930s until it was absorbed by the Société des Avions Bernard (Bernard Aircraft Company) in 1934, which itself was nationalized by the French government in 1935.

Meanwhile, as interest grew around the world for these novel new airplanes, Sweden began to develop an interest of its own in developing a military air service. While Sweden maintained a strict stance of neutrality in the affairs of Europe, certain visionaries within the Swedish Army and Navy believed that the airplane represented more than just a mere curiosity. On July 29, 1909, French aviator Georges Legagneux made the first flight of an airplane in Sweden when he demonstrated his Voisin biplane before a crowd in the Stockholm district of Ladugårdsgärdet (Gärdet) while on a Europe-wide tour, during which he also made the first heavier-than-air flights in Austria and Russia.

The following year, in the spring of 1910, Swedish baron Carl Cederström became the first Swedish citizen to earn an international pilot’s license when he completed his training at Louis Bleriot’s flight school near Paris, France. At 43, Cederström had worked in both Sweden and the United States as an agronomist before entering the automotive industry by renting luxury cars to fellow noblemen in Sweden. Upon returning home, Cederström set out on his own flight demonstrations across Sweden, earning him the nickname “The Flying Baron (or the Aviation Baron)”. By 1913, Cederström established Sweden’s first flying school, Skandinaviska Aviatik AB (Scandinavian Aviation AB), at Malmen in Linköping, near the very site of the modern Swedish Air Force Museum.

At the same time, the Swedish military had seen a slash in defense spending in the aftermath of a parliamentary election. With the Swedish Navy attempting to build an “F-boat”, a larger coastal defense ship with larger guns and heavier armor than any prior Swedish warship, and now being unable to rely on government funds, a committee of prominent in Swedish business and politics was established and called themselves the Swedish Armoured Boat Association (Svenska pansarbåtsföreningen). They led a campaign to secure enough private donations to convince the government to build the new F-boat. Within 100 days, the Association raised 15,021,530 Swedish krona, which was more than enough to build the new coastal defense ship, whose construction was approved by King Gustav V and would become the Sverige (Sweden), with two of ships of her class being constructed with public funds in the coming years (these would become the Drottning Victoria (Queen Victoria) and the Gustaf V (Gustav V). As the Swedish Armored Boat Association had a surplus of funds for the construction of the F-boat, the Swedish Navy decided to use the money left over to purchase its first airplanes, many of which were French-built machines. While the first aircraft acquired for the nascent Marinens Flygväsende (MFV; Naval Aviation Corps) was a Bleriot XI monoplane (later rebuilt into the Nyrop N:o 3), followed by a Nieuport IV monoplane, two Donnet-Lévêque flying boats were acquired for use in Sweden. Of the two flying boats, one was purchased for the Swedish Navy, while another was bought by Carl Cederström.

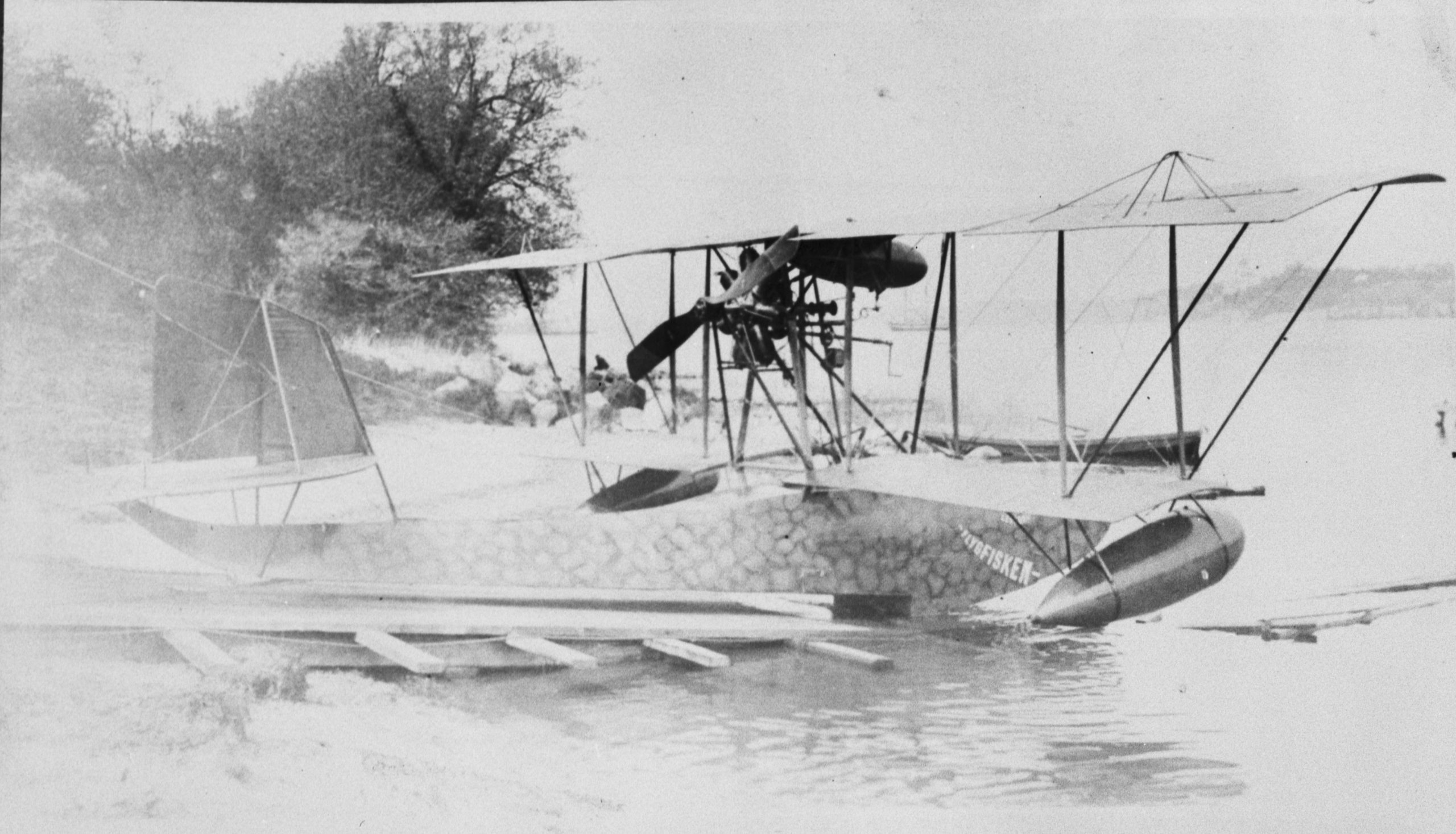

The aircraft sold privately to Cederström was the first of the Donnet-Lévêque flying boats to arrive in Sweden, and by the summer of 1913, he was using it to train pilots at the Skandinaviska Aviatik AB flying school at Malmen. There it was powered by an 80hp Gnome rotary engine and was fitted with landing gear to allow it to operate from land, but it was also flown from nearby Lake Roxen. The aircraft was given a paint scheme depicting the scales of a fish and given the name Flygfisken (Flying Fish).

A second example was also brought to Sweden in October 1913 and was soon designated as L I (Lévêque I) by the MFV and serial number S 22. Since it came without any engine, a 50hp Gnome rotary engine was removed from the first Swedish military airplane, the Nyrop No.3, and installed in the flying boat, which was stationed at Fort Oskar-Fredriksborg on Rindö Island, 21 kilometres (13 mi) northeast of Stockholm for flight training and maritime reconnaissance not only at the Oskar-Fredriksborg fortress but also from Marsgarn in the Stockholm archipelago. Later in 1913, the example bought by Carl Cederström was purchased by the MFV and adopted the designation of L II and the serial number S 23. Despite being repainted in military colors, its pilots would continue to refer to the aircraft as the Flygfisken.

The first two flying boats with the Swedish Navy remained in service at the outbreak of the First World War. Though they were not capable of bearing weapons, they provided valuable flight training experience for Sweden’s first military pilots and provided a set of eyes in the skies above Sweden’s coasts. In April 1916, however, it was determined that the first Donnet-Lévêque, L I/S 22, was too worn out to continue flying, and so after three years it was retired and eventually broken up. S 23 remained in service, though, and in 1917, it was given the new serial number 10.

The Flygfisken (L II/S 23) was first assigned to flight training and maritime reconnaissance at Marsgarn, but over the course of its military service, it would be based at Gothenburg and Karlskrona. According to Swedish aviation historian Jan Forsgren, the aircraft was involved in several accidents during its flying career. On May 14, 1914, Carl-Gustaf Krokstedt was attempting to fly to the island of Gotland when a broken oil pipe forced him to land on the Baltic Sea, where he spent the next seven hours bailing water out of the Donnet-Lévêque until a ferry rescued him and the airplane. Two years later, on May 11, 1916, pilot Arvid Flory was attempting his first take off when a heavy swell ruptured the aircraft’s hull, causing it to overturn and flinging Flory from the cockpit. Fortunately, the young aviator was unharmed and was able to swim back to the overturned flying boat and sit on top of it until assistance came.

Six months later, Flory would have another take-off incident in the restored Donnet-Lévêque, this time on November 6, 1916, when the aircraft overturned yet again while fighting to take off from heavy swells at Karlskrona. The last incident noted by Forsgren occurred on July 26, 1917, when Lieutenant Ivar Sandström crashed at Nynashamn while taking off in foggy weather. Sandström survived this incident but was unfortunately killed in a separate accident in a Morane-Saulnier airplane on September 2, 1917. The Donnet-Lévêque serial number 10 was repaired and returned to service.

By August 1918, the last remaining Swedish Donnet-Lévêque, the Flygfisken, was retired with a total of 131 flight hours. However, its historical significance was not lost on the officials of the time, and so, on September 15, 1919, the last remaining Swedish Donnet-Lévêque, the “Flying Fish,” was donated to the National Maritime Museum in Stockholm. The aircraft was held in storage there until 1936, when it was transferred to the National Museum of Science and Technology (Tekniska museet) in Stockholm and hung from the ceiling of the latter museum’s Machine Hall. By April 1983, the aircraft was in poor condition and was taken down and placed in storage.

After a period of negotiations, it was agreed that the National Museum of Science and Technology would permanently transfer the Donnet-Lévêque to the Swedish Air Force Museum in December 1997. Due to the aircraft’s condition, however, it was not initially displayed at the Flygvapenmuseum, but though it lay in storage, the museum was already making arrangements to begin the long-awaited restoration of the oldest flying boat aircraft in Sweden. Restoration on the Donnet-Lévêque began in 2010 when the Tullingebergsvägen Group/Tullingegruppen, a group of skilled aviation enthusiasts, including retired pilots and mechanics, took on the task of restoring the 97-year-old flying boat on behalf of the Swedish Air Force Museum and the Swedish Aviation Historical Society. They carried out the project at the former Tullinge Airbase south of Stockholm in a workshop located within the former crew mess hall of the Swedish F 18 Wing. New fabric was applied to the fabric, but some of the original fabric has been preserved for the museum’s curators to maintain as part of the museum’s collections department.

The Donnet-Lévêque was refurbished and retained the last livery it was flown with when it was serial number 10 in the MFV, and by September 1913, almost exactly 100 years after its induction into the Swedish Navy, the Donnet-Lévêque L II/S 23/10 was ready to be reassembled, and soon to be sent to its new home inside the Swedish air Force Museum. On December 9-10, 2013, the Flygvapenmuseum held a public ceremony to introduce the Donnet-Lévêque “Flying Fish” to the museum’s exhibition spaces. Among those in attendance were the restorers from the Tullingegruppen, who got to see the fruit of their labor on display for all to see. It is all the more fitting that the Flygfisken should be displayed in the Swedish Air Force Museum, as the museum is near the very site of Carl Cederström’s flying school from which it flew out a century earlier.

In addition to the example displayed in the Flygvapenmuseum, at least two more original Donnet-Lévêque flying boats have been preserved to the present day. The very first Donnet-Lévêque Type A flying boat was later donated by Louis Schreck to the Musée de l’air et de l’espace (the French Air and Space Museum) in 1923. Though this example remains in the museum’s collections, it has been removed from display since 2008 and is currently held in the museum’s storage hangar. Another example remains on display at the Danish Museum of Science and Technology in Helsingør, Denmark. This example, the Maagen 2 (Seagull 2) was one of two Donnet-Lévêque delivered to Denmark in April 1913 and flown by the Dansk Marinens Flyvevæsen (Danish Naval Air Service) and later selected for preservation in 1919. Meanwhile, an FBA Type B can be found on display at the Portuguese Maritime Museum (Museu de Marinha) in Lisbon.

In France, two full-scale replicas are also on display. One can be found at the Biscarrosse Lake Seaplane Museum at Lake Biscarrosse, while an airworthy replica of a Donnet-Lévêque Type C was built by Les Rétro Planes d’Argenteuil at La Ferte Alais, which was first flown in 2017. This replica, F-AZXB, is powered by an 80 hp Le Rhône rotary engine and is maintained in airworthy condition.

As for the Donnet-Lévêque “Flygfisken”, it remains proudly on display at the Flygvapenmuseum, fitted with a set of wooden skis similar to the ones it would have used for winter operations as an amphibious flying boat, and positioned alongside several other pioneering Swedish military aircraft flown by both the Swedish Army and the Swedish Navy from 1912 to the establishment of the Swedish Air Force in 1926. For more information, visit the Flygvapenmuseum’s website HERE.