In the quiet fields and rolling hills of Northern Italy’s Po Valley, a determined group of amateur aviation archaeologists is piecing together a chapter of World War II long considered lost to time. Founded in 2007, Air Crash Po was born from a simple yet powerful mission: to collect and preserve every testimony, fragment, and relic from the air raids that swept through the region between July 1944 and April 1945—when the skies echoed not with victory, but with desperate combat and vanishing souls.

Driven by passion and a profound sense of duty, the team—spurred by founders like Luca Gabriele Merli—combines eyewitness accounts with painstaking archival research to sift through fading memories and fragmented documentation. Their work has restored names and stories to more than eighty lost aircraft and their crews, countering the anonymity imposed by wartime chaos and decades of archival loss. For Air Crash Po, recovery is more than archaeology—it is deeply human. Through recovered serial numbers, personal effects, and meticulous verification, they often deliver long-awaited closure to families who never knew the fate of their loved ones.

“Meeting with the families of pilots thought to be lost forever is an incredible experience,” Merli reflects. “It is very emotional, but it also gives a sense of accomplishment… It is what makes us continue with our mission.” Recently, Luca shared with us a story that perfectly captures this blend of history, humanity, and courage—one that began not in the archives, but in a family’s memory box.

Eighty years after the events, the daughter of a U.S. Air Forces pilot discovered a letter from Italy dated 1946, tucked away among photographs and other keepsakes. Through American researcher Patty Johnson, she contacted Air Crash Po. The letter, written by Italian farmer Tullio Mearelli of Pitigliano, Grosseto, and addressed to Mr. John R. Lion in Hollywood, California, contained names, addresses, and clues that sparked an investigation by researchers Agostino Alberti and Luca Merli.

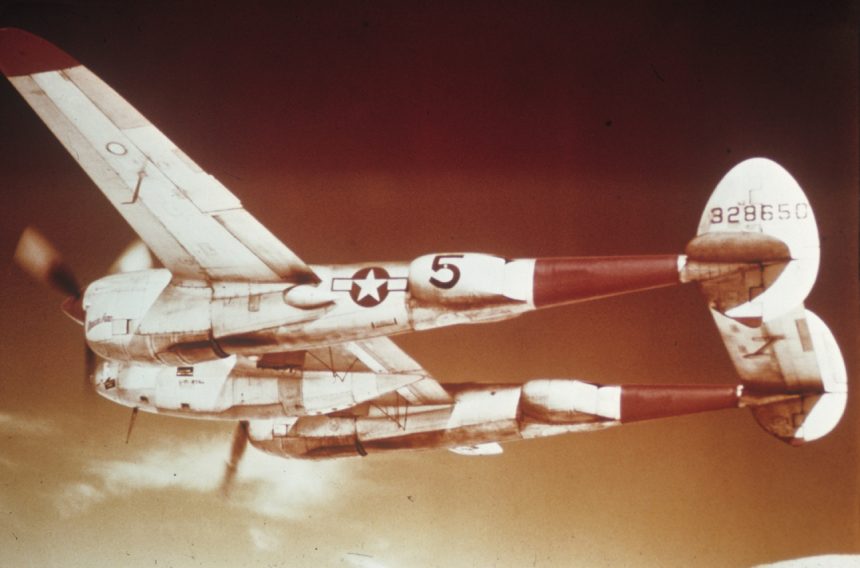

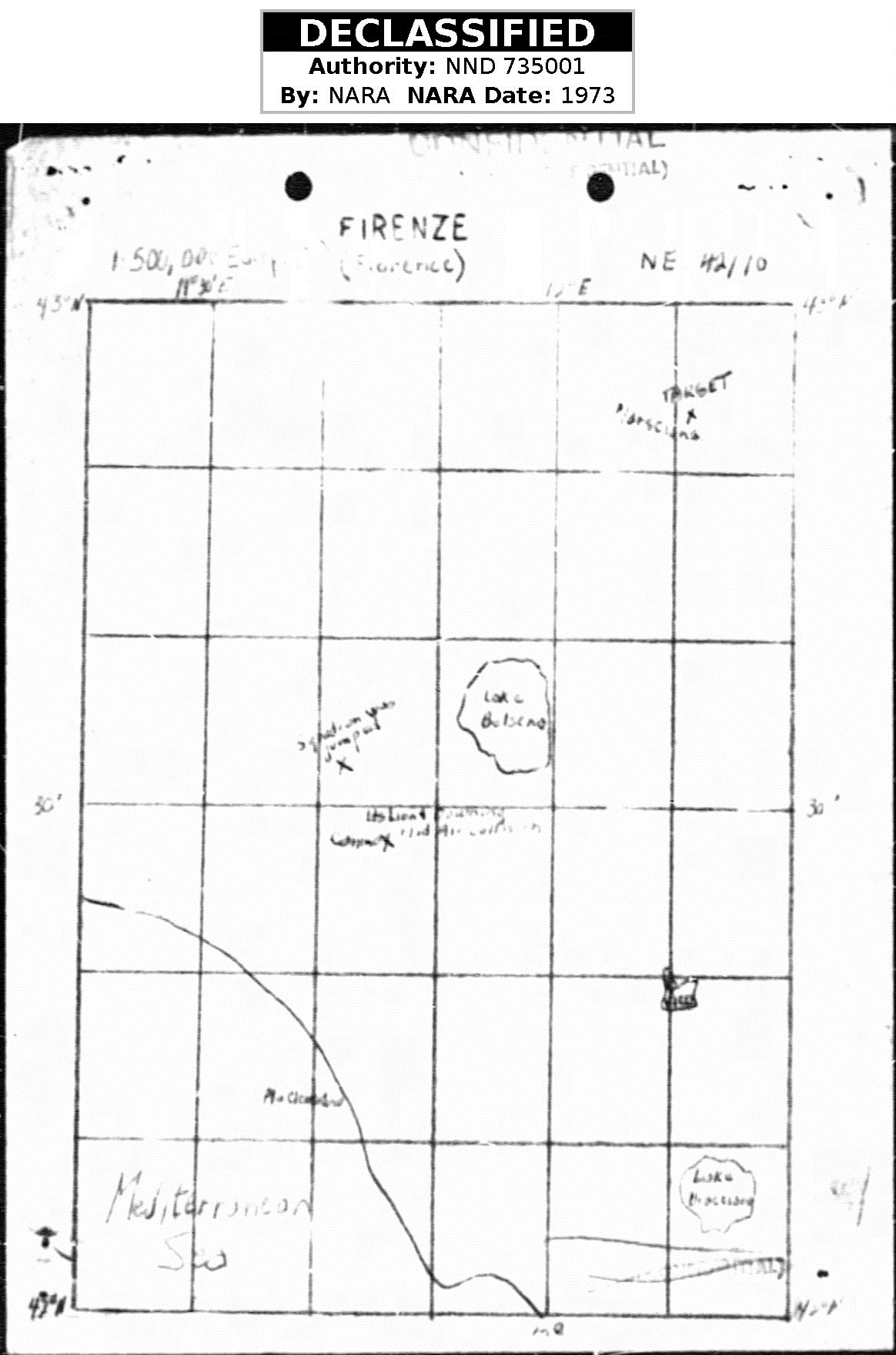

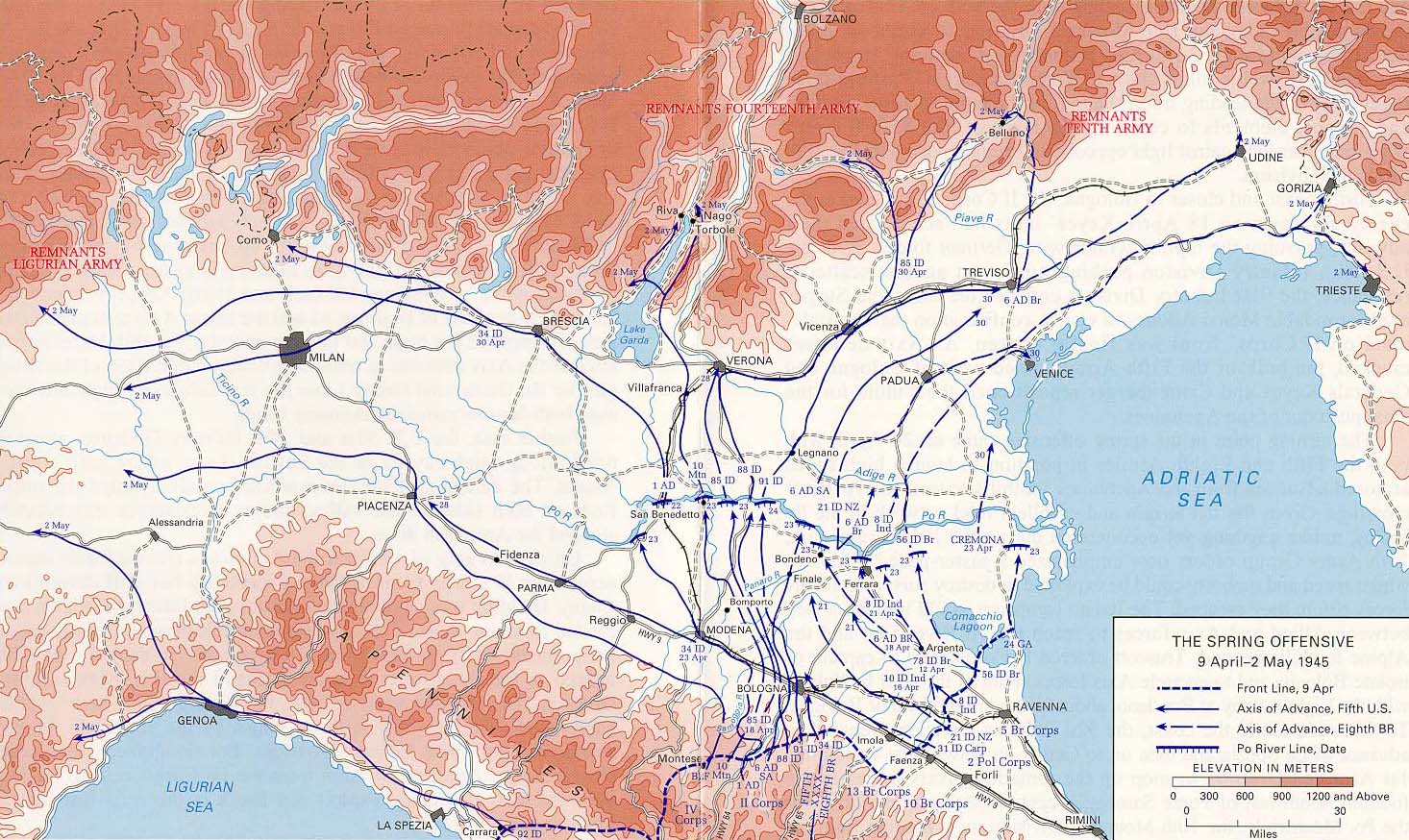

Archival research soon revealed that on October 21, 1943, 1st Lt. John R. Lion was flying a P-38 Lightning with the 1st Fighter Group’s 71st Fighter Squadron on an escort mission from Mateur, Tunisia. That morning, 72 B-26 Marauder medium bombers from the 319th and 320th Bomb Groups took off from bases in Sardinia, tasked with striking rail yards, bridges, and key transport links at Marsciano and Monte Molino, with Acquapendente also listed as a potential target. These bombing missions were part of the Allies’ broader strategy to disrupt German supply and troop movements north of Rome and soften defenses ahead of future advances.

The bomber stream was protected by a strong fighter escort of P-38 Lightnings from the 27th, 71st, and 94th Fighter Squadrons. As the Marauders approached their targets late in the morning, they were intercepted by Messerschmitt Bf 109 G-6s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190s of the Luftwaffe. The German fighters tore into the formation, forcing the escorts to engage in a series of swirling dogfights. The clash was fierce: in the space of minutes, three P-38s and one Bf 109 were brought down.

One Lightning, flown by F/O Spaulding (serial 42-13017), was shot down along the Tyrrhenian coast. The other two—those of Lion and 2nd Lt. Downing Junior—were under intense enemy fire when they collided mid-air, forcing both pilots to bail out over the hills near Pitigliano. The German claim for these victories went to Lt. Franz Trowal of III./JG77, who himself was shot down shortly afterward, his Bf 109 crashing north of Tuscania.

With the mission reconstructed, the “adventure” of the two downed pilots and the big-hearted farmer begins. After landing near the Tuscany–Lazio border, Lion and Downing sought shelter to avoid capture. The downed aircraft and parachutes had not gone unnoticed, and there was a German command post nearby. Fortunately, in the countryside near a farmhouse, the two encountered Mr. Tullio Mearelli, a farmer who worked the surrounding land and lived in the farmhouse next to a building called “La Cantinaccia.” The location was far from the town center, with only dirt tracks for roads. Realizing the imminent danger, Mearelli led the airmen to a hidden cave near a stream and waterfall—an ideal hiding place. For months, with the help of his children, Silvio and Silvana, he kept the Americans supplied with food and essentials until they could safely return to Allied lines.

Today, contact between the Lion family in the U.S. and Mearelli’s descendants in Italy has brought this remarkable wartime bond full circle. Air Crash Po is now seeking relatives of Lt. Downing, hoping to connect both families across continents. When asked why they search for these lost pilots, Merli’s answer is simple: “We do it out of respect for those who lost their lives in the line of duty—and for their families. We do it for passion. We do it out of a sense of duty.” To learn more about Air Crash Po’s operations and to support its work, visit www.aircrashpo.com or Facebook.

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.