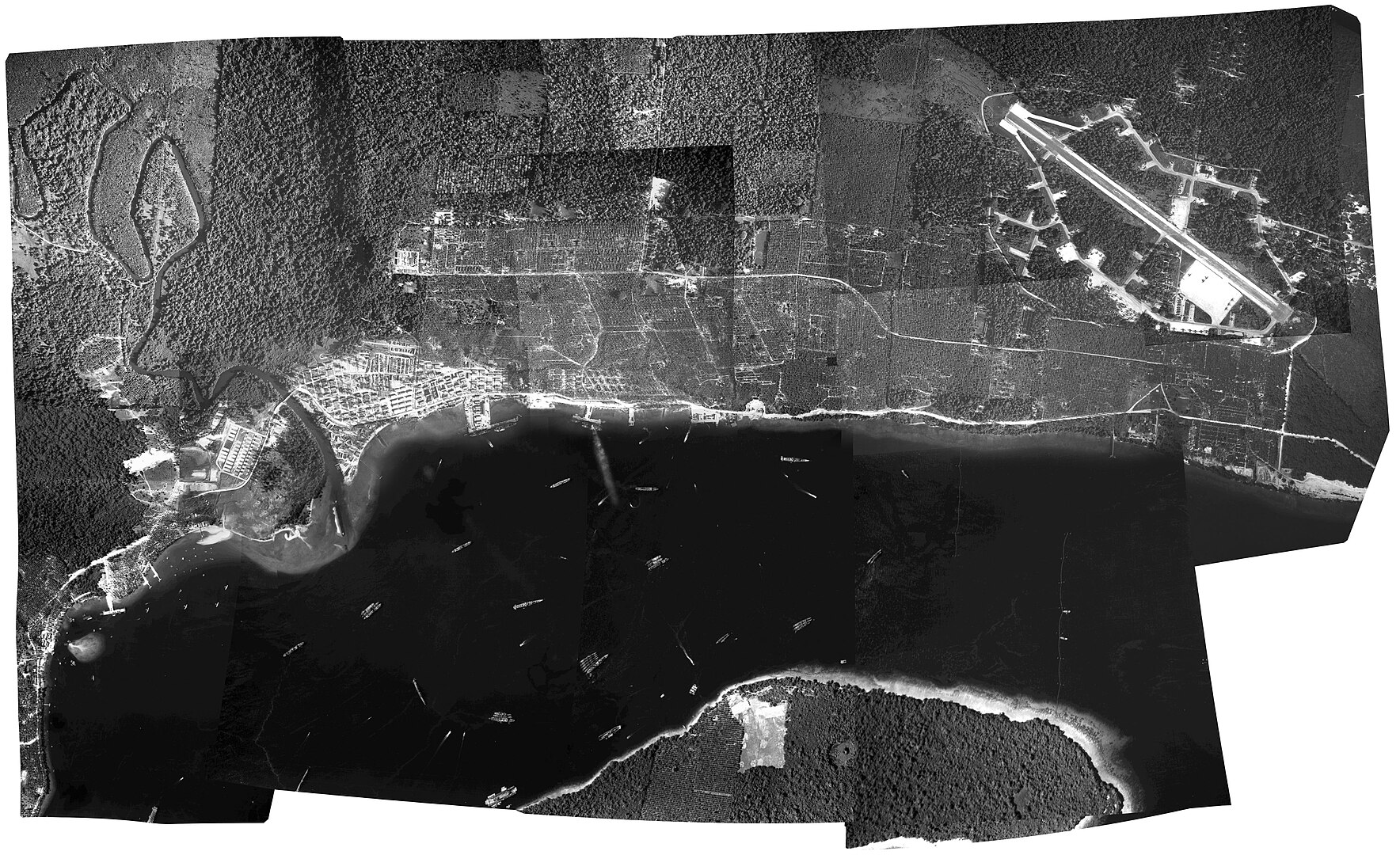

Espiritu Santo, the largest island in Vanuatu, is home to a remarkable number of World War II aircraft wrecks. From bombers and fighters to reconnaissance and transport aircraft, nearly every type of plane that operated from the island’s wartime bases has left traces in its dense jungles or surrounding waters. Some wrecks remain relatively intact, with wings, cockpits, and engines still in place, while others have deteriorated due to the tropical climate or were partially removed by enthusiasts seeking parts for restoration projects abroad.

Under Vanuatu’s Cultural Heritage Act, all wartime artifacts, including aircraft remains, are protected and cannot be removed from the country. In an effort to preserve and document these important relics, the South Pacific World War II Museum has established a comprehensive database to record as many wrecks as possible. This initiative also raises broader questions about heritage management: Should the wrecks remain where they lie, gradually reclaimed by nature and serving as cultural and tourism assets? Should they be recovered for restoration, despite the likelihood that most local residents will never see the completed projects? Or is a balanced approach possible—recovering better-preserved examples for display within a controlled environment, such as the Museum itself?

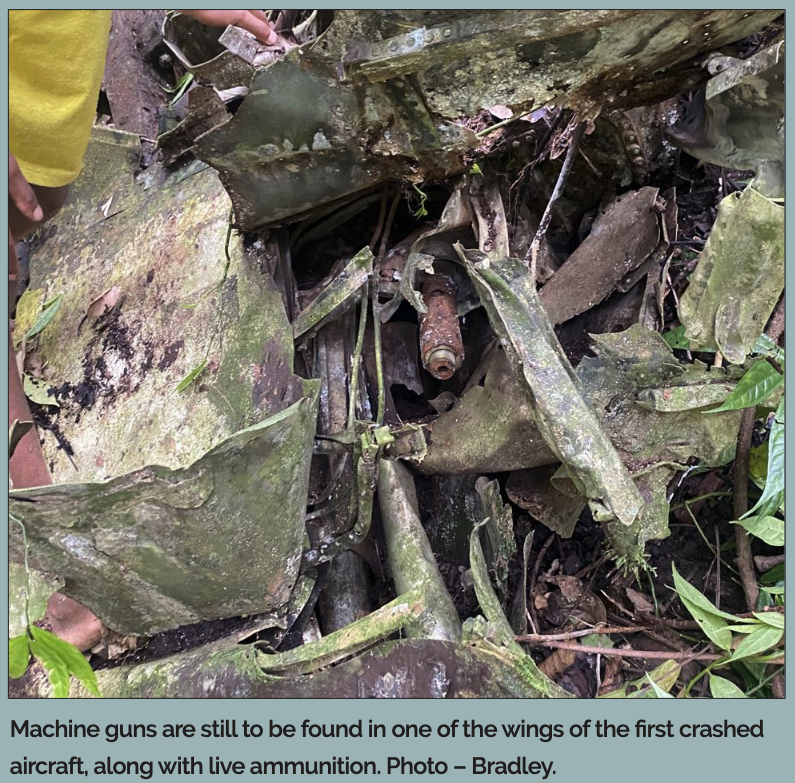

The significance of this work was underscored by a recent discovery. Two weeks ago, the Museum enlisted Luganville resident Bradley, a Ni-Vanuatu local, to investigate reports of an aircraft wreck in northern Espiritu Santo, originally sighted by local villagers Derick and Salomon. Following a lengthy journey and an overnight stay in a remote village, Bradley ventured deep into the jungle with the help of local guides. His efforts were rewarded when he not only located the reported wreck but also uncovered a second aircraft just 250 meters away.

While both wrecks are incomplete, enough remains to confirm that they are World War II aircraft. Identification became the next challenge. Locals also reported two additional wrecks approximately three kilometers northeast and southeast of the site, which the Museum plans to investigate in the future. To aid in the identification process, the Museum turned to Ewan Stevenson of Sealark Exploration, a New Zealand–based non-profit organization dedicated to surveying WWII wrecks throughout the Pacific. Stevenson, known for his encyclopedic knowledge of Santo’s wartime crash sites, has worked with the U.S. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) on several recovery missions to locate and repatriate the remains of missing U.S. service members. The South Pacific WWII Museum has collaborated with Sealark on multiple occasions and shares its commitment to preserving the region’s wartime heritage. According to Stevenson, the majority of crashes on Espiritu Santo—approximately 99%—were the result of training accidents. “A handful of aircraft ran out of fuel in transit, but most ended up in the sea,” he explained. “Pilots low on fuel were trained to make controlled water landings while still having enough power to manage the aircraft.” Beyond training incidents, Stevenson noted that other causes included “bad strafing runs, failed bomb drops, flying into mountains in cloud, uncontrolled spins, mid-air collisions, and low-altitude maneuvers gone wrong—tragic losses of young lives.”

Based on evidence from the wreckage, Stevenson identified both aircraft as Vought F4U Corsairs powered by Pratt & Whitney R-2800-8 radial engines with Hamilton Standard alloy propellers. He believes the two planes collided on April 7, 1944, while piloted by Lt. Larry W. DeCamp and Lt. Harold M. Shafer of Marine Corps Squadron VMF-225. Shafer was killed in the accident, and his body was recovered. DeCamp reportedly survived, either by reaching a nearby beach or drifting downriver to safety.

Unfortunately, significant portions of both aircraft are missing, including the empennages that would have carried their Bureau Numbers (BuNos) 56263 and 56334. “It’s tragic that so much archaeological information has been removed from these sites,” Stevenson observed. “Restoration shops in the U.S. and Australia are often vague about the origins of their materials.” The South Pacific World War II Museum remains committed to documenting and preserving these wrecks within Vanuatu. Although many aircraft were removed from the islands during the 1980s and 1990s, Stevenson estimates that approximately 460 planes were lost in and around the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) during the war—leaving many more still waiting to be found.

Since Vintage Aviation News first covered the South Pacific World War II Museum in January 2023, the museum has made significant strides in preserving Vanuatu’s wartime history. Over the past two years, it has grown into both an educational hub and a community gathering place, reflecting the region’s rich heritage. This update provides a look at the museum’s progress on Espiritu Santo and its ongoing efforts to honor the past. We invite everyone to visit the museum at Unity Park, Main Street, Luganville, and witness firsthand the evolution of the museum. Open Monday to Friday, they warmly welcome everyone to explore, learn, and share in this incredible journey with them. They are not only creating a museum but a lasting legacy for generations to come. If you’d like to be a part of this, consider donating or sharing your story with them; every bit helps us keep the memories alive. In the coming months, we’ll be bringing you further articles about the history of the island during World War II. Click HERE to donate.

Related Articles

Born in Milan, Italy, Moreno moved to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a career as a commercial pilot. His aviation passion began early, inspired by his uncle, an F-104 Starfighter Crew Chief, and his father, a military traffic controller. Childhood adventures included camping outside military bases and watching planes at Aeroporto Linate. In 1999, he relocated to Atlanta, Georgia, to obtain his commercial pilot license, a move that became permanent. With 24 years in the U.S., he now flies full-time for a Part 91 business aviation company in Atlanta. He is actively involved with the Commemorative Air Force, the D-Day Squadron, and other aviation organizations. He enjoys life with his supportive wife and three wonderful children.