Aviation photography has always been more than documentation. At its best, it is art—an attempt to translate sound, motion, and emotion into a single frozen frame. The finest aviation images do not merely show an aircraft in flight; they allow the viewer to feel the vibration of the engine, sense the speed, and inhale the imagined scent of oil and fuel. In an era when digital cameras are ubiquitous and nearly anyone can claim the title of “aviation photographer,” true masters of the craft are increasingly rare. Philip Makanna stands apart. Widely regarded as one of the most influential aviation photographers of the past half-century, Makanna is not simply a recorder of airplanes but an artist in the fullest sense. A painter by training, a lifelong observer of motion and form, and a self-described “ghost” behind the lens, his images have defined how generations of enthusiasts see historic aircraft. From warbirds to racers, from Duxford to Wanaka, Makanna has spent decades photographing not machines alone, but the dreams they represent. Vintage Aviation News recently had the opportunity to speak with Makanna about his life, his philosophy, and his concerns for the future of a vast and historically significant body of work.

Makanna’s story begins far from flight lines and airshows. He grew up on Long Island, New York, the son of a father who worked in the city. His early years followed a conventional academic path, eventually leading him to Brown University. There, Makanna admits with characteristic humor, his academic legacy is mixed at best. He famously failed French multiple times, setting what he jokingly calls a university record, while devoting much of his energy to the rowing crew.

After graduation, he fled the East Coast entirely, riding an old BSA motorcycle west to San Francisco—a city that would become his lifelong home. Yet aviation itself did not begin with a camera. Like so many others drawn to flight, Makanna traces his passion back to childhood, building model airplanes in a basement and imagining himself in the skies. Photography entered his life through art rather than aviation. Makanna began his adult career as a painter, earning a master’s degree at the University of California, Berkeley. That foundation, he believes, shaped everything that followed. He does not see himself primarily as an airplane photographer, but as an artist who happens to work with airplanes as his subject. Composition, light, motion, and emotion have always mattered as much to him as rivets and markings.

When asked to describe his philosophy, Makanna does not offer a manifesto. Instead, he returns to a simple idea: he photographs dreams. His favorite line, he says, is that he has spent his life photographing the dreams he had as a little boy. After more than five decades behind the lens, he still sees his work as part of an artistic life split between aviation and fine art. Now in his mid-eighties, Makanna reflects on the sheer volume of work he has produced. Nearly five decades of aviation calendars—46 editions completed, with the next nearing print—stand as only one visible measure of his output. Yet he is candid about his uncertainty. His work, he knows, appeals deeply to a relatively small audience. It is historically important, but he worries about its long-term fate, about whether it will be preserved, understood, or quietly lost despite careful backups and archives.

The evolution of aviation photography itself has been dramatic. Makanna sees digital technology as the single greatest change—transforming cameras, workflows, and the speed at which images move around the world. Yet the aircraft themselves have also changed the landscape. When he began photographing warbirds in the early 1970s, particularly during his time around the Confederate Air Force in South Texas, flyable historic aircraft were rare. Spitfires, for example, could be counted on one hand. Today, dozens fly worldwide, restored to standards that would have been unimaginable half a century ago.

Airshows have multiplied, historical interest has grown, and access to remarkable aircraft has expanded. Yet Makanna remains philosophical about the future. World War I aircraft are now more than a century old; World War II aircraft are approaching that milestone. How long such machines can continue flying depends on economics, craftsmanship, and commitment—factors never guaranteed.

Despite his towering reputation, Makanna leads a remarkably insular professional life. He rarely follows other aviation photographers and works largely alone. When pressed to name influences, he reaches far beyond aviation, pointing instead to Jean-Henri Lartigue, the French photographer born in 1894 whose work spanned aviation, people, and everyday life. Lartigue photographed pioneers like Louis Blériot and captured the joy and motion of the early 20th century with an enduring spirit that Makanna deeply admires.

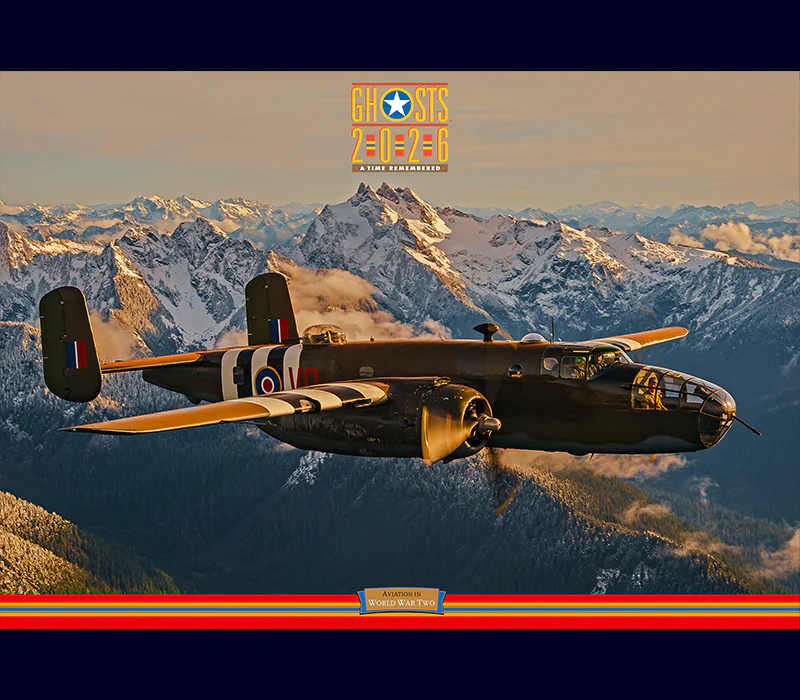

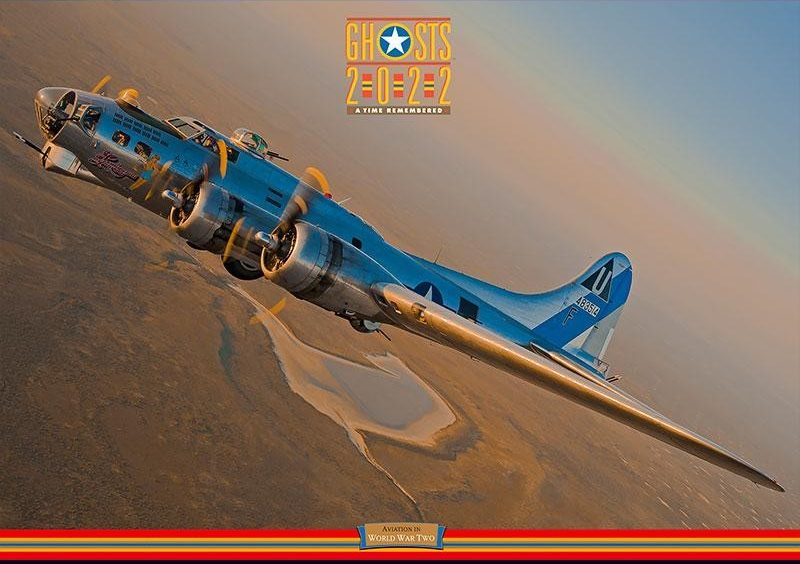

Asked to name his most memorable experiences with historic aircraft, Makanna struggles—not from a lack of moments, but from too many. South Texas marked his early years, but England, and Duxford in particular, became central to his life’s work. Beginning in 1990, he returned to Duxford year after year for nearly three decades, drawn by its history, its aircraft, and the uniquely British relationship with aviation heritage. New Zealand also left a profound mark, especially flying among the mountains near Wanaka, a place Makanna describes as transformative.

As the conversation turns toward the future, Makanna’s tone becomes reflective, even uneasy. Sitting at his computer, he is surrounded by more than 210,000 photographs—most of them aviation images. Though backed up in multiple locations, he worries about permanence. What happens if the systems fail? What happens after he is gone? He does not claim to have answers. His hope is simply that the work can be secured, preserved, and valued for what it represents. Philip Makanna’s legacy is not merely a collection of stunning photographs. It is a visual history of living aviation, captured by someone who never stopped seeing airplanes as dreams made real. In an age of instant images and fleeting attention, his work reminds us that aviation photography, at its highest level, is still about patience, vision, and feeling—and about honoring the magic that first made us look up.

Phil Makanna’s legendary GHOSTS calendars return for 2026, showcasing breathtaking air-to-air photography of WWI and WWII combat aircraft. Each large-format calendar pairs striking imagery with historical context, aircraft specifications, and silhouette profiles, making them a must-have for aviation enthusiasts and collectors alike. Makanna has also authored some of the most highly regarded aviation photography books ever published. For more information, click HERE.