We have periodically presented reports by Chuck Cravens detailing the restoration on an ultra-rare Beechcraft AT-10 Wichita WWII advanced, multi-engine trainer, but it has been almost a year since our last update. As mentioned in the previous articles, the project belongs to the Cadet Air Corps Museum and comprises the remains of several airframes, but will be based upon Wichita 41-27322. The restoration is taking place at the world-renowned AirCorps Aviation in Bemidji, Minnesota, and we now have another update on the progress as it stands so far….

Where Did All the AT-10s Go?

At the end of WWII, the USAAF had thousands of surplus airplanes on its hands. The task of disposing of or selling those planes was enormous. Some could be profitably sold to foreign air forces. Other surplus aircraft were useful in a civilian role. For example, thousands of surplus C-47s would become a mainstay of civilian companies that flew cargo and passengers for many years after the war. Some still are earning their keep with commercial operators to this day.

Other aircraft had less utility as civilian planes. The AT-10, with a limited useful load and fairly high operating cost was one of these. 2,371 AT-10s were produced by Beech and Globe. In 1946, the War Assets Administration listed 1,930 of them for sale at various locations around the country. 80% of the entire production of Wichitas was on the block as surplus. The only AAF plane with more examples on surplus sale listings in 1946 was the Vultee BT-13 (4,280).1

1 William Larkins, Surplus WWII U.S. Aircraft, BAC Publishers, Inc.; 1st edition (December 1, 2005)

Many of the AT-10s that were eventually purchased were simply bought for their engines. In 1942 an AT-10 cost the government $42,688, but by the time they were sold as surplus, the price was less than $1,500 and many bought them just for their Lycoming R-680-9 engines that were suitable for use in surplus Stearmans, then finding a ready market as crop dusters. At 295hp, the Lycoming was also a performance upgrade to these PT- 13s which had similar R-680s rated at just 220hp. Most often, the AT-10s engines and other usable parts were removed, while the rest of the wooden airframe was left to rot away, leaving just the non-perishable aluminum components from the cockpits and nacelles.

The other significant reason for the lack of surviving Wichitas is that despite the forward fuselage and engine nacelles being made of aluminum, the bulk of the aircraft, even the fuel tanks, was made of plywood. Plywood was a non-strategic material, which made AT-10 construction possible at a time when aluminum was in high demand for combat aircraft, and the material’s lightness contributed greatly to the AT-10’s superior performance. However, plywood doesn’t fare well for long periods outdoors, so the aircraft remaining at the end of WWII quickly succumbed to the elements. Indeed, barely a handful made it onto the civil registry.

Only one intact Wichita remains, and this is on static display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. Once completed, AirCorps Aviation’s AT-10 restoration will become the only flying example of an AT-10 in the world.

DURAWOOD

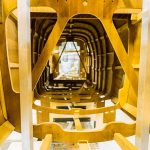

“Durawood” is called out in many AT-10 drawings and mentioned in manuals, and figuring out what it was and how to replicate it was one of the AT-10 project’s challenges. After much research, we determined that Durawood was a material composed of many layers of 1/32 inch thick walnut, laminated together with resorcinol glue. Once cured, it is stronger than a block of wood and was used in stress points and where major components were bolted together.

LONGERONS

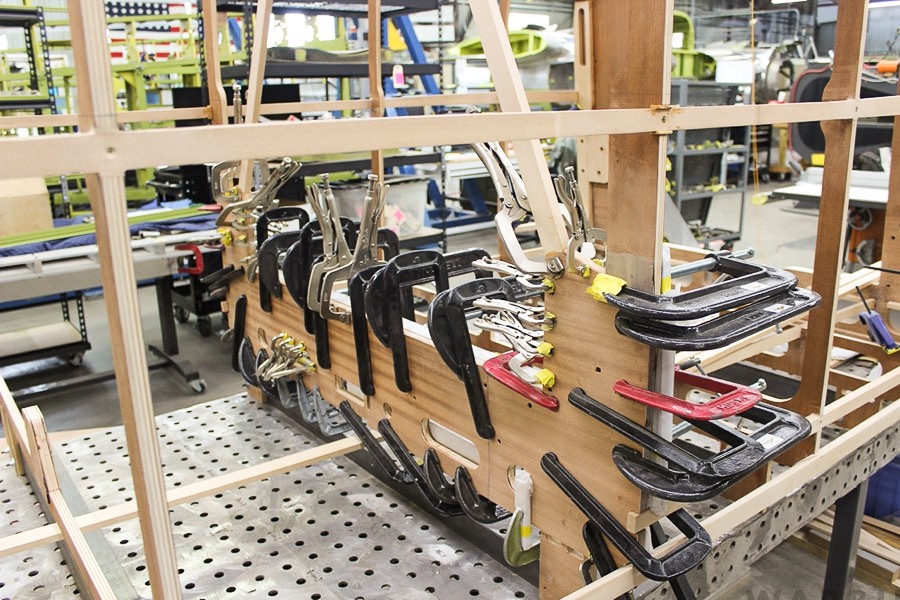

After the bulkheads and formers were mounted in the fixtures, the longerons had to be formed and installed. They have some complex tapers and bevels.

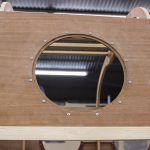

“PORTHOLE” WINDOWS

One of the identifying characteristics of the AT-10 is the porthole shaped windows just aft of the cockpit.

SKINNING THE AT-10

The AT-10’s skin is manufactured from 1/8th inch thick, 3-ply mahogany and poplar plywood. In many areas it must be steamed or soaked in ammonia to make it pliable enough to conform to curved fuselage sections.

The next step was to attach the forward cockpit area and the vertical fin to the main wooden fuselage.

It is great to see such visible progress on this restoration of such an extremely rare and unique piece of history.

WANT TO GET INVOLVED?

Be a part of helping the AT-10 return to the skies!

Contact Ester Aube at:

[email protected] or 218-444-4478

And that’s all for this edition of the AT-10 Restoration Report. Many thanks to Chuck Cravens and AirCorps Aviation for this article. Should anyone wish to contribute to the Cadet Air Corps Museum’s efforts, please contact board members Brooks Hurst at 816 244 6927, email at [email protected] or Todd Graves, [email protected]. Contributions are tax deductible.

Related Articles

Richard Mallory Allnutt's aviation passion ignited at the 1974 Farnborough Airshow. Raised in 1970s Britain, he was immersed in WWII aviation lore. Moving to Washington DC, he frequented the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum, meeting aviation legends.

After grad school, Richard worked for Lockheed-Martin but stayed devoted to aviation, volunteering at museums and honing his photography skills. In 2013, he became the founding editor of Warbirds News, now Vintage Aviation News. With around 800 articles written, he focuses on supporting grassroots aviation groups.

Richard values the connections made in the aviation community and is proud to help grow Vintage Aviation News.