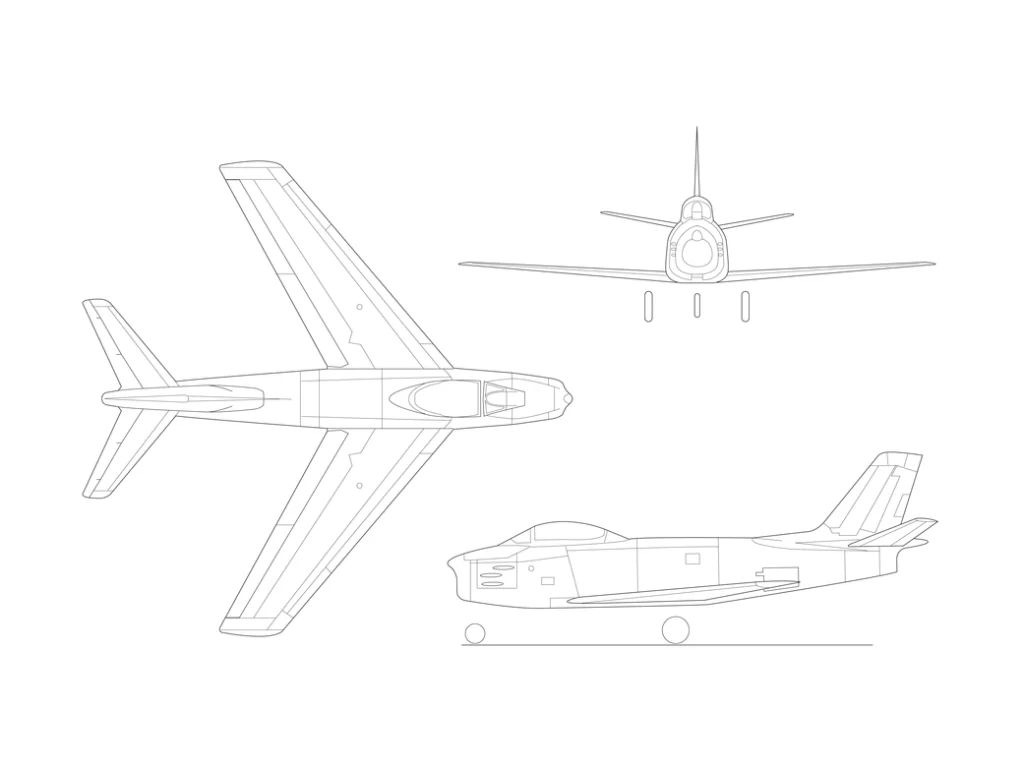

In the early years of the jet age, speed was no longer enough. Engineers had learned how to fly fast in a straight line, but as aircraft approached the speed of sound, control became uncertain. Wings began to buffet, and noses pitched up without warning. Pilots found that the airplane they trusted at 400 miles per hour did not always behave the same way at 500. The North American F-86 Sabre arrived at that moment. It was America’s first operational swept-wing fighter, shaped by aerodynamic research gathered from Germany at the end of World War II. The research indicated that a swept wing delayed the compressibility effects encountered at high subsonic speeds, and swept-wing aircraft could be controlled at supersonic speeds compared to a straight-winged aircraft of the same general configuration. In the Korean War, the Sabre proved that idea in battle by destroying almost 800 MiG-15s with the loss of fewer than 80 F-86s. The airplane could dive past Mach 1, and in the hands of experienced pilots, it handled cleanly at speeds that had troubled earlier straight-wing jets. But while the Air Force fought with it, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which was later known as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), studied it.

From 1951 to 1959, the NACA High-Speed Flight Station at Edwards, California, which was later renamed NASA Dryden Flight Research Center (now Armstrong Flight Research Center), flew several F-86 variants as research and chase aircraft. These included F-86A, F-86D, F-86E, and F-86F. Some were on loan from the Ames Aeronautical Laboratory, and one was assigned directly to the station. They were not flown for combat missions; they were flown to measure behavior. The Sabres served as chase aircraft for experimental programs and as research platforms for handling qualities studies. The aircraft used a General Electric J47-GE engine. The A and F models had a fuselage length of 37 feet 6 inches, with a 35-degree swept-back wing and a wingspan of 37 feet 1 inch. At Edwards, its guns were often removed and replaced with instrumentation. In 1951, the F-86A was used to investigate maneuvering accelerations and buffeting at high altitude, both with and without wingtip fuel tanks. The goal was to understand what happened to a swept-wing fighter as it approached the transonic region.

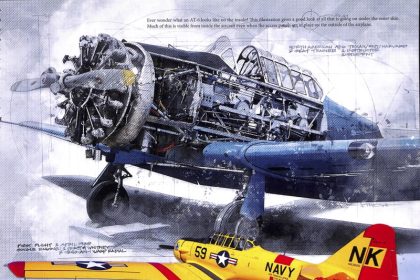

At the same time, other aircraft at Edwards were pushing the envelope further. The Douglas D-558-2 Skyrocket, one of the early swept-wing research airplanes, was exploring transonic and supersonic flight in a joint program involving NACA, the Navy, and Douglas Aircraft. The Skyrocket first flew in 1948 and later became the first airplane to reach Mach 2. It was built specifically for research, whereas the F-86 was an operational fighter adapted for study. The two aircraft used to fly together were the Sabre, which was chased, and the Skyrocket, which gathered high-speed data. The problem they were studying was known as pitch-up. As swept-wing aircraft approached high subsonic speeds or operated at high angles of attack, the nose could rise suddenly and without command. This was not just uncomfortable; it could become dangerous during takeoff, landing, or tight maneuvering. Early Skyrocket flights in 1949 revealed how serious the problem could be, and NACA engineers began an investigation to gather data on longitudinal and lateral stability and control, wing and tail loads, and lift, drag, and buffeting characteristics at high speed.

By measuring how the F-86 behaved at high speed, engineers could see whether their wind-tunnel ideas actually matched what happened in the sky. When they compared the Sabre’s behavior with that of purpose-built research aircraft, they began to understand the difference between theory on paper and what a pilot actually felt through the controls. Through the early 1950s, three Douglas D-558-2 Skyrockets flew more than 300 times. Some versions were carried aloft under a Navy P2B (Navy version of the B-29) and released at altitude before lighting their rocket engines. In November 1953, NACA pilot A. Scott Crossfield took one to Mach 2.005, becoming the first man to fly twice the speed of sound. The flights gathered important data on stability, control forces, structural loads, drag, heating, and even how rocket exhaust could disturb the airplane’s directional balance at very high speeds. The Skyrocket explored the outer edge of the envelope. The F-86, on the other hand, provided an answer to the kind of flying an operational pilot might actually experience. Together, the two aircraft connected research and operational reality, turning uncertain high-speed flight into something pilots could understand and trust.

The F-86D and F-86E also flew at the NASA High-Speed Flight Station in December 1958. These flights were research flights for handling qualities studies of a swept-wing fighter aircraft. The Sabre’s data helped confirm that wing fences improved recovery from pitch-up, and leading-edge slats, when fully deployed, could eliminate the tendency across most of the transonic range. These lessons influenced later fighters, and the movable horizontal stabilizers seen on the century-series aircraft of the late 1950s owed part of their refinement to knowledge gained during these tests. The Sabre was not the fastest research aircraft at Edwards, but it provided a full-scale, operational example of a swept-wing fighter behaving in real air. It showed how wind-tunnel predictions compared with flight and helped engineers understand buffeting, control forces, and stability limits at the edge of the sound barrier. Like other aircraft in the Flight Test Files series, the F-86, despite being a fighter jet, helped build the future of aviation and became part of a broader effort to make supersonic flight predictable and controllable. Check our previous entries HERE.