Since the 1940s, the Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards, California, now known as the Armstrong Flight Research Center, has been the place where aviation ideas are taken out of theory and tested in the open air, over a vast desert lakebed that forgives mistakes but never hides them. Many aircraft that arrived at Dryden were already proven machines. A few arrived with questions so fundamental that no one yet knew whether the idea itself would survive flight. The Bell XV-15 belonged to that second group, which was built to combine the vertical lift of a helicopter with the speed of a fixed-wing airplane. Helicopters could lift straight up and land almost anywhere, but they were slow and inefficient over distance. Airplanes, on the other hand, were fast but demanded long runways. The XV-15 was an attempt to bridge that gap through a controlled transition.

The XV-15 did not begin as a production aircraft. Its development started in 1973 as a joint Army and NASA effort, funded as a “proof of concept” program. The goal was not to sell an aircraft, but to prove whether a tiltrotor, an aircraft that could rotate its engines and rotors in flight, could move smoothly and safely between vertical helicopter flight and horizontal airplane flight. By 1977, Bell Helicopter Textron built two aircraft; one became NASA 702, and the other NASA 703. By September 1979, airworthiness testing and initial proof-of-concept flights had been completed. What remained was to test and gradually push the aircraft to operate safely at its extreme design limits, such as higher speeds or higher altitudes, in front of engineers who remembered earlier tiltrotor attempts that had ended badly.

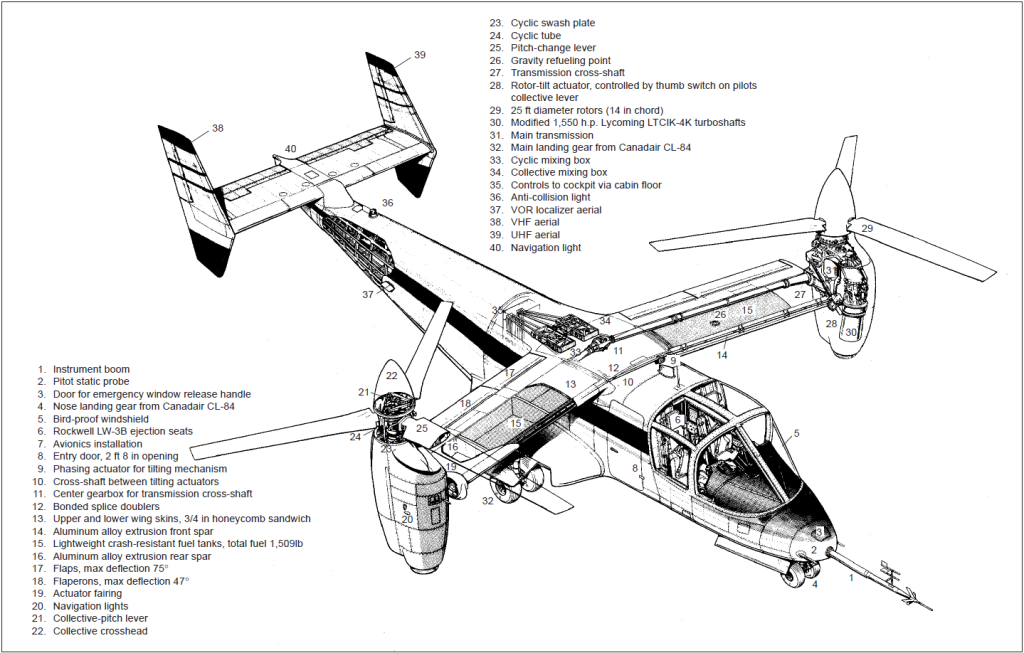

Earlier tiltrotor experiments, such as Bell’s own XV-3, had shown promise but problems such as sudden pitch changes, rotor interference, and control coupling, which had nearly ended the concept entirely. The XV-15 was designed from the beginning to counter these problems. The aircraft was powered by two Lycoming T-53 turboshaft engines, linked by a cross-shaft that drove three-bladed metal rotors, each 25 feet in diameter, allowing either engine to keep both rotors turning if one failed. By placing the engines and transmissions at the wingtips, Bell reduced loads on the cross-shaft and simplified structural stresses during transition.

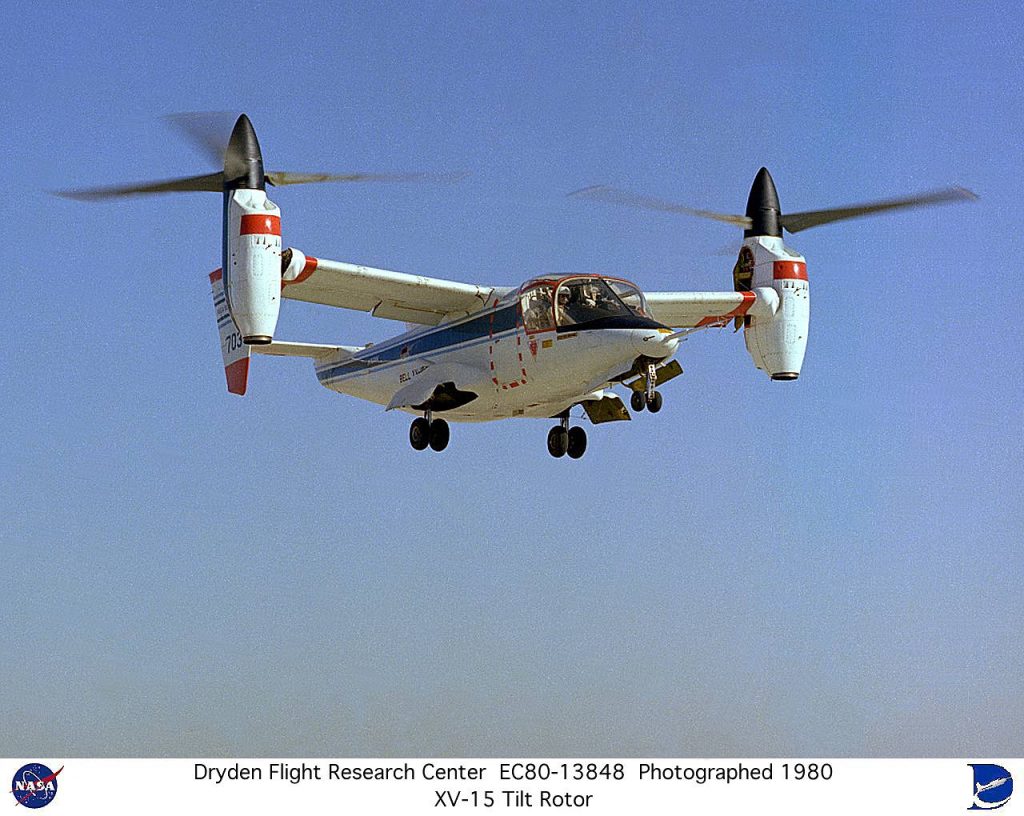

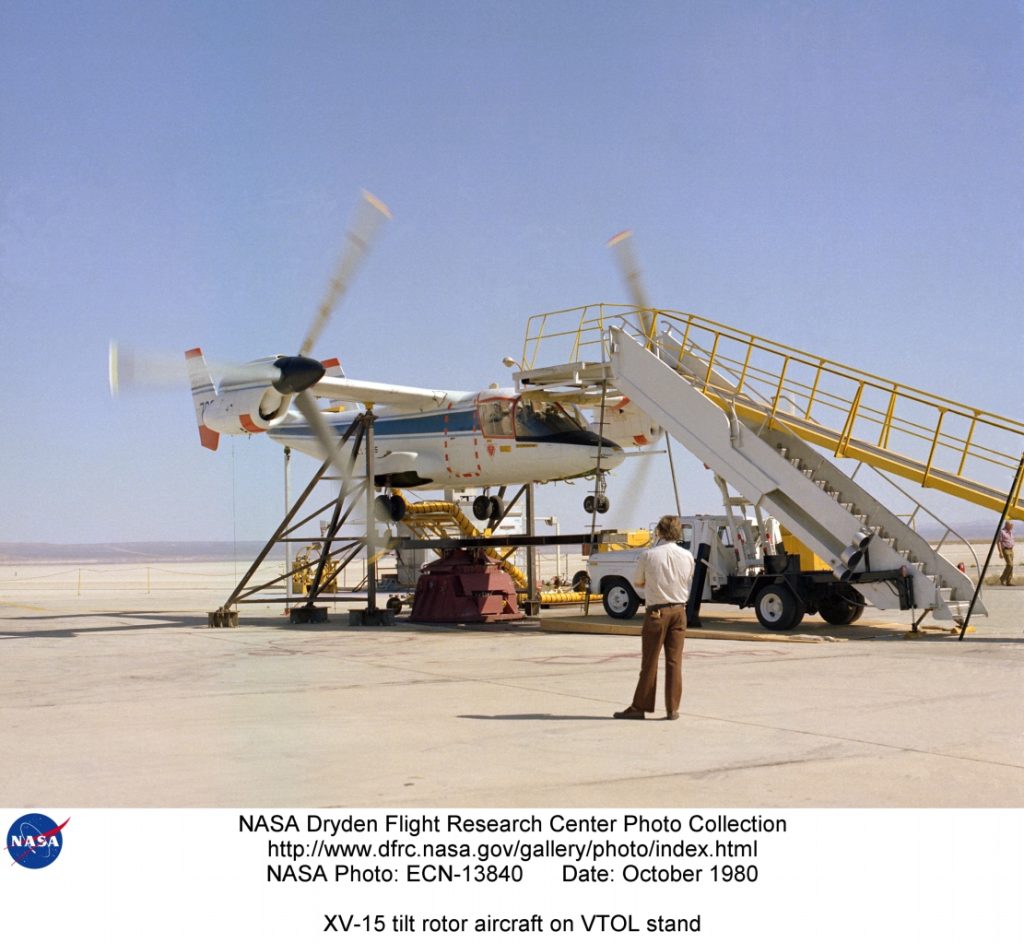

Most importantly, the engines and rotors tilted together as a single unit. In vertical takeoff and landing mode, the proprotors pointed straight upward, producing lift like a helicopter. In airplane mode, they rotated forward, acting as propellers while the wing assumed the lifting role. The transition between these two states, the moment where most tiltrotors failed, became the focus of the entire program. NASA’s first XV-15 flight at Dryden took place in October 1980, operating from the Army contingent at Edwards Air Force Base. The aircraft lifted vertically, hovered, and behaved exactly as engineers hoped. Still, the engineers were cautious as the hover was the easy part; transition was everything.

In vertical flight, the XV-15 could simply rise into the air and hover there for close to an hour, behaving like a helicopter. Once flying, it could be operated in three distinct ways: as a helicopter, in a halfway state between helicopter and airplane, or fully converted into an airplane. The actual change from one to the other took only 10 to 15 seconds, but those few seconds mattered more than anything else, because that was when the lift moved from the spinning rotors to the wing and the aircraft’s aerodynamics quietly reshuffled themselves in ways no wind tunnel could fully predict. Test pilots moved into this phase carefully. Nacelles were rotated only a few degrees at first, and airspeed was allowed to build slowly. Each conversion revealed small truths about rotor behavior, wing loading, and control harmony.

Shortly, the XV-15 began performing at its best, rotating the proprotors continuously from vertical to horizontal while accelerating through the transition corridor. During this phase, it lifted smoothly and transferred from the rotors to the wing. After this, the aircraft behaved less like a helicopter and more like a turboprop airplane. Operating as a conventional airplane, the XV-15 could cruise for more than two hours. It first reached estimated cruise speeds of around 345 mph at 16,500 feet, and then a maximum speed of 375 mph at the same altitude, far more than conventional helicopters. The XV-15 showed that tiltrotors could deliver payloads over distances greater than 115 miles using roughly half the fuel of a helicopter. It demonstrated that aircraft could take off vertically, cruise like airplanes, and land in confined spaces without specialized infrastructure. In short, it offered a new category of flight.

Between 1980 and 1982, both XV-15 aircraft flew regularly at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center, slowly building confidence one flight at a time. By the end of the program, the tiltrotors had logged more than a thousand flights in every possible mode, including hover, transition, and airplane flight. Some of those flights were about fixing problems rather than chasing performance, as engineers refined stability systems to calm unwanted oscillations and adjusted flaperons to deal with retreating blade stall. As pilots spent more time in the cockpit, the control laws evolved as well, shaped as much by feel as by mathematics. Eventually, the XV-15 left the safety of the desert. Tests in Arizona pushed it into hot-and-high conditions, where the air was thin, and margins were smaller. Later, the aircraft was taken into operational demonstrations, including shipboard trials, to see whether a tiltrotor could safely land on a moving deck and remain controllable in strong winds. All flight tests showed positive results.

By the time the program concluded, the XV-15 transformed tiltrotor flight from a risky idea into a reality. The XV-15 never entered production but made the Bell-Boeing V-22 Osprey possible. The V-22 heavily utilized aerodynamic data, control law strategies, and operational insights derived from the successful XV-15 tiltrotor research aircraft. By the time the V-22 first flew in 1989, the hardest questions had already been answered by XV-15. In the long history of flight testing at Dryden, the test aircraft stands as one of the turning points of modern aviation. And like many aircraft in the Flight Test Files, the XV-15 did not change the world by entering service, but by proving that the world could be changed. Check our previous entries HERE.

Related Articles

Kapil is a journalist with nearly a decade of experience. Reported across a wide range of beats with a particular focus on air warfare and military affairs, his work is shaped by a deep interest in twentieth‑century conflict, from both World Wars through the Cold War and Vietnam, as well as the ways these histories inform contemporary security and technology.