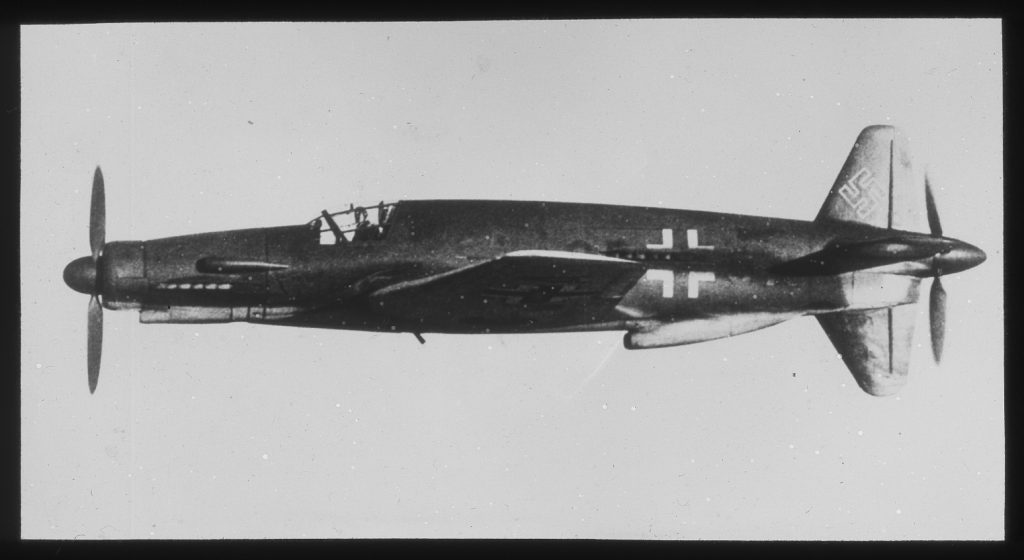

The Dornier Do 335 was one of the fastest propeller-driven aircraft ever built, and it stood out immediately because it looked nothing like the fighters flying around it during World War II. Instead of engines mounted on the wings, it had one engine in the nose pulling the aircraft forward and another engine in the rear pushing it from behind. With such a layout, engineers hoped it would give the aircraft the power of two engines without the drag and control problems that usually came with twin-engine designs.

In flight, the idea worked better than many expected as the test pilots found the Do 335 fast, stable, and easy to handle for such a large and heavy aircraft. If one engine failed, the aircraft did not yaw to one side, which was a common problem with conventional twin-engine fighters at the time. With both engines running, it accelerated quickly and could outrun almost anything powered by pistons. The Germans confirmed that a pilot flew a Do 335 at a speed of 763 km/h (474 mph) in level flight at a time when the official world speed record was 755 km/h (469 mph), which made it one of the fastest propeller aircraft ever flown.

Do 335: Ahead of its Time

The Do 335, with two liquid-cooled engines each delivering about 1,750 hp, also included features that were unusual for piston aircraft of that era. It had an ejection seat, and because the rear propeller made a normal bailout extremely dangerous, the aircraft was designed so that the tail fin and rear propeller could be blown off before the pilot ejected. It used tricycle landing gear, which made ground handling easier, and it carried heavy armament and the option to carry bombs internally. On paper, and even in testing, it looked like a very capable multirole aircraft.

The Do 335 also had some problems, including its 9,600 kg (21,000 lb) weight when fully loaded, which put constant strain on the landing gear and the airframe every time it took off or landed. The rear engine was placed inside the fuselage, which often caused it to overheat, and routine maintenance became more difficult than on conventional fighters. By the time the aircraft was finally ready, Germany no longer had the fuel, the time, or even the usable airfields needed to operate and support such a demanding design. By late 1943 and early 1944, when the Do 335 was still being tested, the war between the Allied and Axis powers had already turned against Germany, with Allied fighters dominating the skies, and factories were under constant attack. By the end of the war, Dornier finished building as many as 48 Do 335 jets, and another nine were under construction. The German combat units also received several preproduction aircraft about 10 months before the war ended; however, no pilots flew Do 335s in combat.

A Pilot’s Testimony

What those final months of war were really like becomes clear through the experience of German test pilot Hans-Werner Lerche, who flew one of the last Do 335s in April 1945. By then, German aircraft were rarely seen in the sky, fuel was scarce, and air raids disrupted almost every flight. When orders came to move the remaining test aircraft out of the Rechlin test center, Lerche chose the Do 335, both because it was fast and because there were few other aircraft left to fly. Even getting airborne was difficult as one Do 335 was grounded by a damaged tire caused by bomb fragments on the runway, leaving Lerche with only one aircraft to fly. Air raids delayed departure until evening, and when he finally took off, he stayed at a very low altitude to avoid Allied fighters and antiaircraft fire. The aircraft cruised so fast that navigation became difficult, especially since the Do 335’s compass was unreliable due to interference from the rear engine.

Fuel soon became another concern as the engines guzzled about 900 liters of fuel per hour, and the transfer pumps that moved fuel between tanks failed during the flight. Lerche relied on landmarks like lakes, railways, and highways instead of instruments, knowing that pushing on blindly would likely end badly. As darkness approached, he diverted toward Prague, choosing a known airfield over an uncertain journey. Landing there brought new trouble when the landing gear refused to extend, forcing him to use the emergency system in the dark. A belly landing would have been extremely dangerous because of the aircraft’s shape and rear engine, but the gear finally locked into place. The Do 335 had once again shown both its strengths and its unforgiving nature.

None Flew in Combat

The journey continued days later in poor weather and worsening conditions. On one leg, tracer rounds suddenly passed close to the aircraft, forcing Lerche to push the engines to full power and drop to treetop height. No aircraft caught him, and the engines held, but the incident showed how vulnerable even the fastest aircraft could be at that stage of the war. By the time Lerche reached southern Germany, airfields were being bombed almost continuously. He parked the Do 335 fully expecting it to be destroyed, yet by chance it survived. His final flight took the aircraft to Oberpfaffenhofen, where Dornier personnel watched in surprise as one of their most advanced designs arrived intact, just days before the war collapsed completely.

In total, fewer than 50 Do 335s were completed, and none flew in combat. The Do 335 had pushed propeller technology to its limits, but it arrived too late in a war that no longer had room for a new experiment or second chances. The Dornier Do 335 was neither a failure of engineering nor an unrealistic idea. It was an aircraft built for circumstances that no longer existed, and like many designs in the Grounded Dreams series, it stands as a reminder that timing matters as much as technology. Check our previous entries HERE.