During World War II, the US used various bombers such as the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, and the Boeing B-29 Superfortress for strategic daylight bombing. These bombers, with a flying range of around 3,000 miles, were usually escorted by fighters such as the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and the North American P-51 Mustang. However, as World War II ended and the world moved toward the Cold War, the US had developed the advanced Northrop B-35 and Convair B-36 bombers with a nearly 10,000-mile range, which even the P-51 couldn’t match. In this “Grounded Dreams: The Story of Canceled Aircraft” article, we look at the XF-85 Goblin, a tiny fighter built to fly inside a bomber, and why dangerous recoveries made the concept unworkable. Check our previous entries HERE.

The rise of parasite fighters

At the time, aerial refueling was a new, risky concept, and pilot fatigue during long-range missions over Europe and the Pacific also demanded new solutions. The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), which initially wanted to develop remotely piloted vehicles to escort the new bombers, settled on a bizarre solution to carry parasite fighters in the B-36’s belly as the most practical defense. The parasite fighter concept was not new; the British Royal Air Force, US Navy, German, and Russian forces had already tested them. In fact, Soviet engineer Vladimir Vakhmistrov’s Zveno project in 1931 flew up to five fighters launched from Polikarpov TB-2 and Tupolev TB-3 bombers. In August 1941, TB-3s carrying Polikarpov I-16 dive bombers attacked Romania’s Cernavodă bridge and Constanța docks, then struck a Dnieper bridge at Zaporozhye held by German troops, which became the only incident where parasite fighters saw combat.

With this problem in mind, the USAAF asked aircraft companies in December 1942 to design a small fighter that could be carried by a bomber. Over the next two years, the requirements evolved as technology improved. By early 1945, the Air Force decided the aircraft should be jet-powered. McDonnell was the only company that responded to both versions of the request. Its first idea placed the fighter partly outside the bomber, but this created too much drag and was rejected. In March 1945, McDonnell submitted a cleaner redesign, which later became the XF-85 Goblin.

Design of Goblin

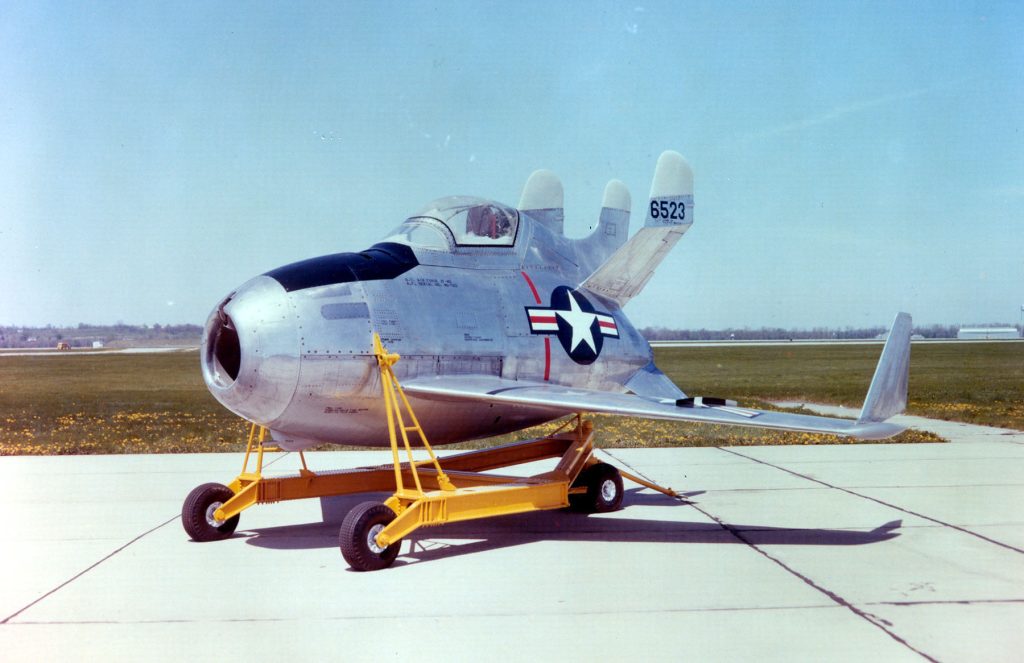

The new design featured a potato-shaped fuselage, three fork-shaped vertical stabilizers, dihedral horizontal surfaces, and 37-degree swept-back folding wings to fit bomb bay constraints. The overall length of the aircraft was measured at 14 ft 10 in with a 21 ft wingspan when extended, and the fuel capacity of 112 US gallons allowed it to fly for 30 minutes. A retractable hook at the center of gravity extended from the nose upper section. The empty weight fell just under 4,000 pounds. McDonnell deleted the landing gear to save mass; however, test aircraft later added a fixed steel fuselage skid and spring-steel wingtip runners for emergency landings. Despite tight quarters, pilots received a cordite ejection seat, bailout oxygen, and a high-speed ribbon parachute. Four .50 caliber machine guns mounted in the nose provided armament.

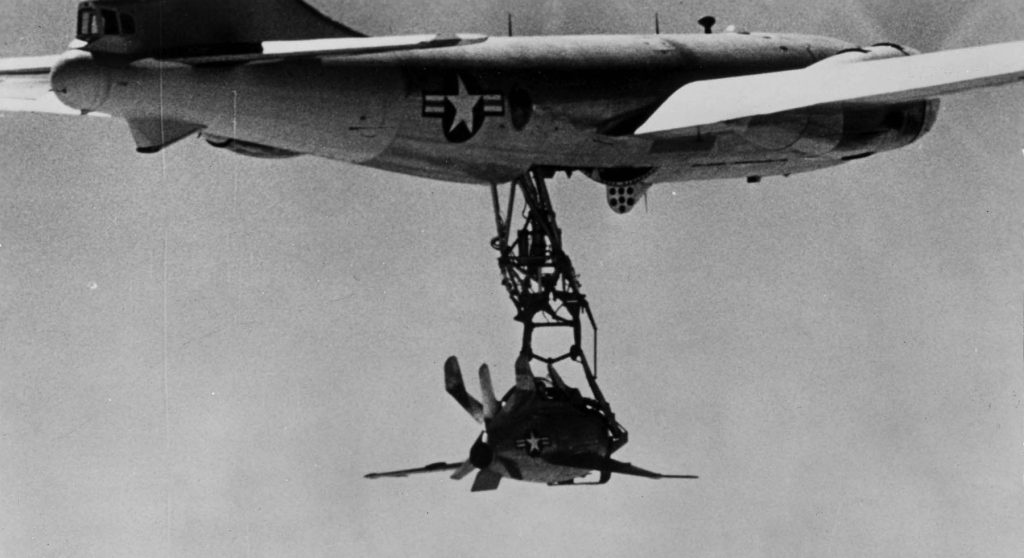

The trapeze was how the Goblin got out and back in. The bomber lowered the trapeze from the bomb bay, and the Goblin’s Westinghouse J34-WE-22 engine air-started while hanging. Pilot pulled back on the stick to unhook the nose latch and drop free. Recovery meant flying up from underneath to snag the trapeze with that same nose hook, then the bomber winched it back inside. The plan was to build mixed B-36 fleets that could work both as bombers and as flying aircraft carriers. Starting with the 24th B-36, the aircraft was designed to carry one XF-85 Goblin, with the idea that each bomber might eventually carry as many as four. In fact, planners even considered converting up to 10 percent of all B-36s to carry three or four Goblins instead of bombs.

The recovery failure

The USAAF signed a letter of intent to procure two prototypes in October 1945, with the contract finalized in February 1947. Wooden mock-ups passed USAAF engineering reviews in 1946 and 1947. McDonnell completed the development in late 1947. Flight testing began in 1948 using a modified B-29 mothership. Pilots successfully launched the XF-85, but the turbulent slipstream under the bomber made recovery hazardous. Roughly half of all flights ended with emergency landings after failed hookups. Test pilot Edwin L. Schoch ejected from the second prototype after a failed recovery on 26 October 1948. No XF-85 ever launched from or returned to a B-36. The program ended in late 1949 as aerial refueling proved more practical for conventional fighters.

The XF-85 project cost $3,210,664 and flew a total of two hours and nineteen minutes, according to the Strategic Air Command & Aerospace Museum. It showed that the B-36 bomber’s turbulent airflow tossed the tiny fighter around during recovery, and its 21-foot wingspan could not generate enough lift to climb back into position. Even highly experienced test pilots struggled to line up the hook. Emergency landing skids prevented total losses, but they also made it clear that the design left almost no room for error. By 1949, aerial refueling had improved enough to let regular fighters like the F-84 Thunderjet stay with B-36 bombers on long flights. Refueling in the air was much easier than trying to hook a tiny fighter onto a bomber. Once tanker aircraft came into use, the Goblin no longer made sense. McDonnell then moved on to building normal fighters like the F-101 Voodoo.

Related Articles

Kapil is a journalist with nearly a decade of experience. Reported across a wide range of beats with a particular focus on air warfare and military affairs, his work is shaped by a deep interest in twentieth‑century conflict, from both World Wars through the Cold War and Vietnam, as well as the ways these histories inform contemporary security and technology.