Located on Alaska’s Seward Peninsula on the very edge of the Bering Sea, Nome, Alaska is arguably best known for “The Three Lucky Swedes” who discovered gold in Anvil Creek in 1899 and became the co-founders of the city the following year and the 1925 diphtheria epidemic that claimed the lives of seven children and captured national attention with the Serum Run, that saw teams of sled dogs rushing the vital antitoxin from Nenana to Nome, which has been immortalized in the annual Iditarod Sled Dog Race.

Nome’s military history can be traced back to the days immediately following the gold rush, when Fort Davis was established three miles east of the city in 1900. For the next eighteen years, more than 130 soldiers were posted at the fort to maintain law and order. Today, the area is private property, albeit abandoned, and is known locally as “Fort Davis fish camp”.

Nome’s military history can be traced back to the days immediately following the gold rush, when Fort Davis was established three miles east of the city in 1900. For the next eighteen years, more than 130 soldiers were posted at the fort to maintain law and order. Today, the area is private property, albeit abandoned, and is known locally as “Fort Davis fish camp”.

Even today, the only way to reach Nome is by air, sea, or dogsled. There are no roads connecting the city to the rest of Alaska, and it’s closer to Siberia than to any other major city in the state. When flying into Nome Airport (PAOM), you are landing at the former Marks Army Airfield (named after Major Jack S. Marks, who was shot down and killed in the Aleutians in 1942), which was home to a few fighter and bombardment squadrons. During the war, Russian military personnel were a common sight in town and out in the field, which was the jumping off point for pilots ferrying Lend-Lease aircraft across the Bering Sea to far-flung battlefields on Russia’s western front. Over 10,000 aircraft staged through Marks AAF during World War II. Historians with a keen eye might notice Higgins boats and six-inch guns scattered in and around Satellite Field, three miles north of the city.

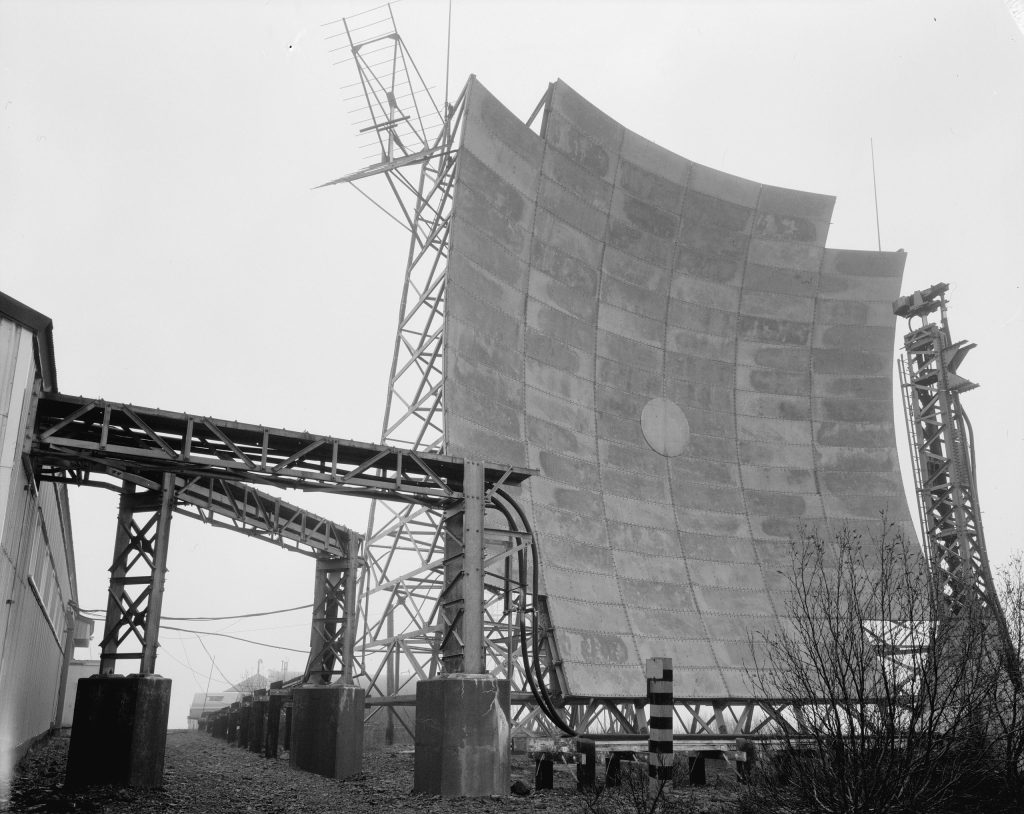

This rich history all but hides in plain sight, going unnoticed as 21st-century locals and tourists go about their daily business. There is, however, a piece of Cold War history overlooking the city that one cannot help but notice. Perched on the top of the 1,083-foot Anvil Mountain are the four 60-foot White Alice antennas that have stood vigil for over seventy years. The antennas, technically tropospheric scatter anntenas, were once part of the White Alice Communications System (WACS) which were part of a United States Air Force telecommunication network that connected remote Air Force sites, such as Aircraft Control and Warning (AC&W), Distant Early Warning Line (DEW Line) and Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS), to command and control facilities and in some cases it was used for civilian phone calls.

The latter was especially advantageous to the residents of Nome, because it provided a long-distance connection to the outside world, as the April 15, 2016, edition of the Nome Nugget explained, “…a resident of Nome wanting to make a long-distance call had to make a reservation to use one of two circuits out of town. White Alice boosted that number to a whopping 15 circuits and expanded the opportunity for chitchat.” Of course, the advent of satellite communications in the 1970s and 80s made the system obsolete ,and it was shut down in 1985.

According to the Bering Straits Native Corporation website, “Beginning in the 1990, a debate occurred in Nome concerning whether the antennas should be removed or be left standing. The area immediately surrounding the antennas contained various contaminates, and the sheathing on the back of the structures contained lead paint and asbestos.” In a 2010-2011 clean-up process brought about the removal of some panels containing asbestos and “millions of pounds of soil” were removed to Oregon for disposal. This work was done by the U.S. Air Force, after which chain link fences were erected around the antennas, which remain today. The Nome Nugget article continued, “The Nome Common Council voted 4-1 to save the antennas Monday evening from looming destruction…. That they are the last ones standing, it breaks my heart we would take them down,” Sue Steinacher said during the public comment period.

By 2016, the Anvil Mountain antennas, which have long been referred to as “Nomehenge” by locals, were the last intact remains of the White Alice system. Strange as it may sound in this epoch of satellite navigation, the White Alice site still serves as a navigational aid for mariners when low fog obscures the coastline and low-lying land near Nome. While you can see antennas from just about anywhere in Nome, you can get a closer look by heading up Anvil Mountain. That is more than a notion, however, as there are only two ways to get there: 1) an hour hike, or 2) two unprepared roads that require a high-clearance vehicle. If you are hearty enough, though, and have the time to make the trip, you will be rewarded with sweeping views of Nome, the Bering Sea, and the surrounding tundra. At the top, you’ll see various alpine flowers, and wildlife including American golden plovers and muskox The author and his wife were set to embark on the HX Expeditions cruise ship SS Roald Amundsen, on July 8, 2025, so we flew into Nome the day before with a bold road trip plan, 1) Make the 142-mile round trip to Teller, 2) drive to the top of Anvil Mountain, and 3) take the Nome-Council Highway to the Train to Nowhere, a 64-mile round trip. By the end of the day, we’d driven over 200 miles on the gravel “highways” of the Seward Peninsula. Our philosophy is that we might not ever come back, so do as much as possible.

Our rental was an AWD Ford Explorer that was equipped with a hefty set of BFGoodrich Baja Champion All-Terrain tires, which was more than we needed for the drives to Teller and halfway to Council, but it was barely enough vehicle for the climb up Anvil Mountain. The 1.7-mile Anvil Mountain Tower Road that leads to the site is not well-maintained, heavily rutted, and topped with loose gravel and small rocks with larger rocks hidden underneath that could be fatal to an oil pan if not negotiated carefully. As such, our maximum speed on the road was three mph. For a majority of the climb, the towers are not visible and don’t fully reveal themselves until you round the last bend at the top. On this day, we were startled to see a female muskox and her calf just a few feet away. I took a few photos from the safety of the car as they made their way into the brush.

Once we walked around the top of the mountain, the views truly were stunning. Below us to the south was the city of Nome and the cold, cobalt-colored Bering Sea beyond. Sweeping in every other direction was the hills, rivers, and tundra of the Seward Peninsula, which are alive with vibrant colors during Alaska’s all-too-brief summer. Standing atop Anvil Mountain in stark contrast to this stunning natural beauty are the gray, metallic sentinels, the last of their kind, of a bygone era when the superpowers were on the verge of wiping it all off the face of the Earth.

Related Articles

Stephen “Chappie” Chapis's passion for aviation began in 1975 at Easton-Newnam Airport. Growing up building models and reading aviation magazines, he attended Oshkosh '82 and took his first aerobatic ride in 1987. His photography career began in 1990, leading to nearly 140 articles for Warbird Digest and other aviation magazines. His book, "ALLIED JET KILLERS OF WORLD WAR 2," was published in 2017.

Stephen has been an EMT for 23 years and served 21 years in the DC Air National Guard. He credits his success to his wife, Germaine.