Since his childhood, Randy Malmstrom has had a passion for aviation history and historic military aircraft in particular. He has a particular penchant for documenting specific airframes with a highly detailed series of walk-around images and an in-depth exploration of their history, which have proved to be popular with many of those who have seen them, and we thought our readers would be equally fascinated too. This installment of Randy’s Warbird Profiles takes a look at the Western Antique Aeroplane and Automobile Museum’s Curtiss JN-4D Jenny, U.S. Army Air Service s/n SC-1382.

This particular airworthy aircraft was one of 252 “JN” model aircraft manufactured by the Curtiss Aeroplane Company and was stationed at Kelly Field, Texas, in 1918 along with other JN-4s. While on a training flight piloted by Richard A. Von Hake on May 16, 1918, it went into a tailspin, crashed, and was written off. It was bought by Hood River, Oregon residents Terry Brandt (founder of Western Antique Aeroplane and Automobile Museum (WAAAM), Tom Murph,y and Jeremy Young after finding it online.

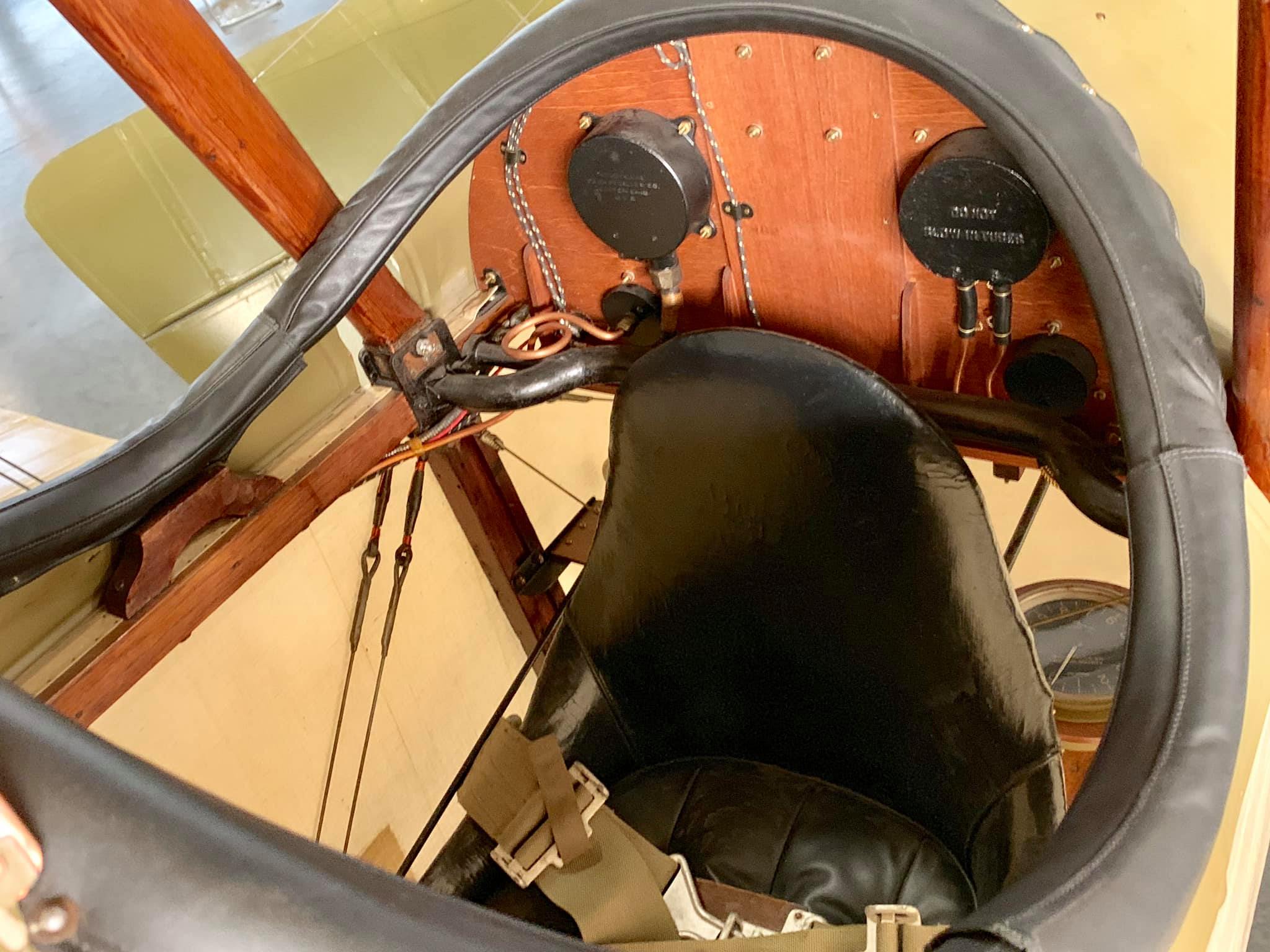

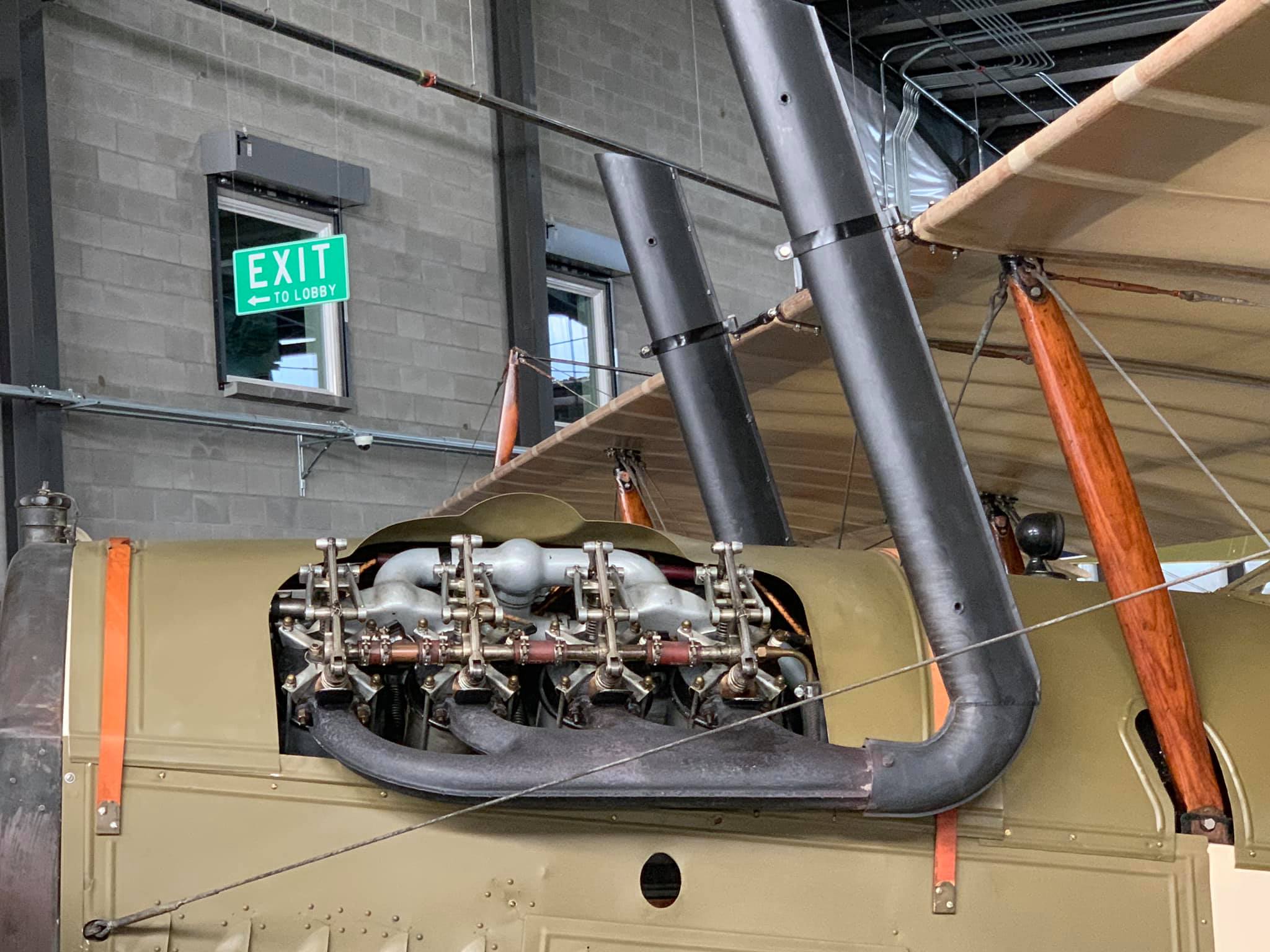

It had been dismantled in the 1920s and stored in a barn in Ohio since then. The boxes of parts were largely complete, and as a result, the rebuilt airframe is made up of more than 95% original parts – the turnbuckles (around 300 of them) are original. The tires, bungee cord suspension, control wires, and fabric were replaced. Jenny’s were originally covered with either Grade A Cotton or Irish linen at the time they were designed. This aircraft is covered with a 50 to 60-year-old stock of Irish linen, part of a stock of aircraft parts that had been owned by the grandfather of Jeremy Young, WAAAM’s first director, and the dope finish was applied by hand with horsehair brushes as was the practice (Dacron is the standard modern replacement as far as I know). Restoration cost $400,000 USD and took two years and three months, and it first flew again with its Curtiss OX-5 engine on May 17, 2008.

This is by no means an all-inclusive description of the aircraft type. The Jenny design was commissioned by Glenn Curtiss, who hired experienced European designer Benjamin Douglas Thomas, and was built by Curtiss Aeroplane Company as part of the company’s “JN” series of biplanes – the “Jenny” nickname derived from the “JN” series. It was the first mass-produced American aircraft, with over 6,000 built. The ailerons were originally controlled by a shoulder yoke (with the pilot leaning left and right) in the aft cockpit, but were replaced by a wheel, stick, or yoke by this D model. While generally not armed some advanced trainers had machine guns and bombs.

Powered by a Curtiss OX-5 engine. The main undercarriage was the V-configuration common at the time, which had bungee cord (shock cord) suspension – “bungee” or “bungie” is thought to be British slang for India-produced rubber. Skis could be fitted for year-round operations, particularly in Canada. It could be fitted with a turtle-deck behind the cockpits to serve as an air ambulance. An estimated 95% of U.S. WWI pilots trained in a Jenny and most Canadian pilots flying the JN-4 “Canuck” variant which was also flown by the British Royal Flying Corps.

A JN-4 is credited with the first true dive-bombing attack, although dive-bombing was tried by Commonwealth pilots in World War I but in a horizontal flight path. In early 1919, U.S. Marine Corps pilot Lt. Lawson H. “Sandy” Sanderson was stationed in with VF-4M in Haiti during the U.S. occupation of Haiti campaign. He mounted a carbine barrel in front of the windshield of his JN-4 as an improvised bombsight and loaded a bomb in a canvas mail bag that was attached to belly of his Jenny. In support of USMC troops trapped by Haitian “Cacos” rebels, he made a single-aircraft attack of at least 45-degrees (considered steep at the time), dropping his bomb at about 250 feet. While his nearly vertical pull-up maneuver almost tore the aircraft apart, the attack was a success and led to Lt. Sanderson developing further dive-bombing techniques beginning in 1920. In 1925, “Sandy” became the first squadron commander to lead VF-9M (which later became VMF-1).

Amelia Earhart, Charles Lindbergh and Bessie Coleman, the first African American female aviator, trained in the Jenny. In 1927, new regulations for airworthiness, maintenance and pilot licensing requirements came into effect and the Jenny was not able to meet the new directives, so by 1930, the Jenny was illegal to operate in most parts of the United States until the 1950s when Jennys came back into acceptance with the Vintage Airplane Movement.

As far as fin flash, in 1917, the US Army Air Service adopted the pattern of blue forward and red farthest aft (the same as French WWI aircraft); and in January 1918, the order came down to switch the pattern; and in August 1919, the original 1917 pattern was re-adopted. However, some aircraft never got changed during the 1918 era, resulting in both sequences being visible in vintage photos of Jenny aircraft in service in the United States. Possible armament: a fixed, forward-facing twin .30 cal. Marlin machine gun mounted on the cowling and synchronized through the propeller; a 30 cal. Lewis machine gun on a scarf ring universal mount on the rear cockpit; and bomb racks. My photos at WAAAM in Hood River, Oregon, where, as of this writing, almost all of the 75 aircraft on display are flightworthy.

About the author