From an original article by Dr. Steve Liddle CEng FRAeS, Vulcan to the Sky Trustee and Principal Aerodynamicist at Visa Cash App RB F1 Team

Aerodynamics at the Edge: How Innovation Shaped the Avro Vulcan’s Wing

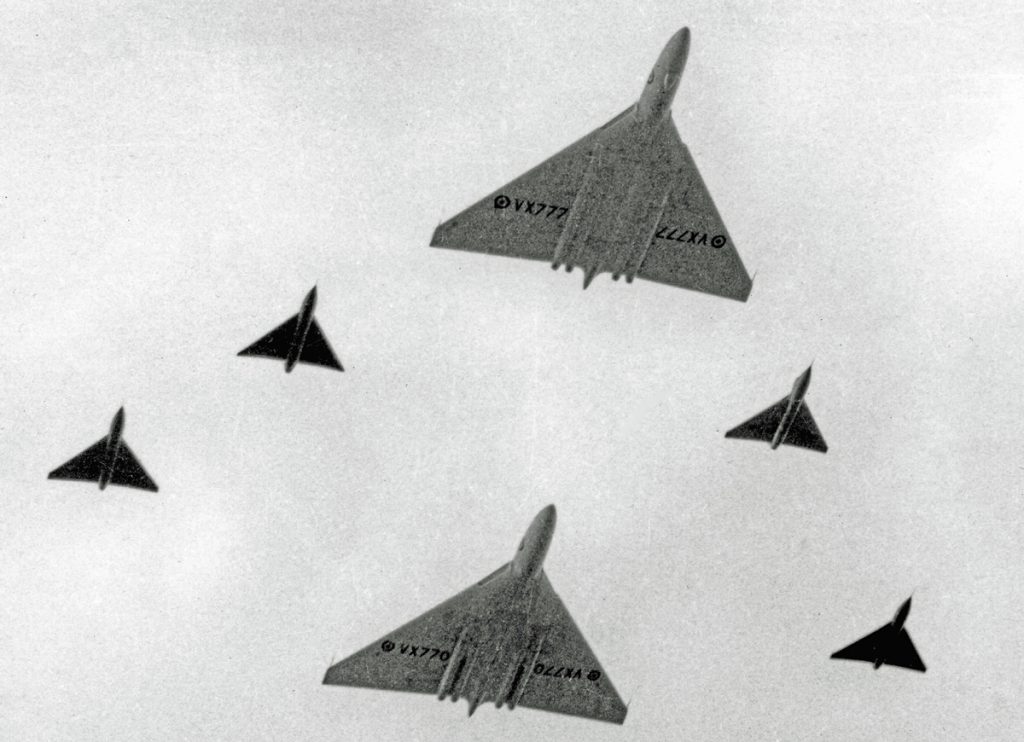

The iconic Avro Vulcan, though affectionately dubbed the “Tin Triangle,” was anything but a basic delta-wing design. Behind its distinctive silhouette lay a deep well of aerodynamic innovation, trial, and refinement. At a time when Britain was investing heavily in cutting-edge strategic bombers—the V-bomber force—the Vulcan stood out as an aircraft that pushed the very boundaries of known aerodynamic science. Dr. Steve Liddle, a Vulcan to the Sky Trustee and Principal Aerodynamicist at Visa Cash App RB F1 Team, has revisited this remarkable period in British aviation engineering through a series of technical reflections originally published on the Vulcan to the Sky Trust’s LinkedIn page. His analysis draws from rare archival material, including declassified research conducted at the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) in Farnborough in the early 1950s.

A Design Driven by Speed and Altitude

The Vulcan’s development stemmed from a need to outpace and outmaneuver enemy defenses during the Cold War. High speed and altitude were essential, and that required a level of aerodynamic sophistication previously unseen in bomber design. One of the key challenges faced by engineers was airflow behavior at high subsonic and transonic speeds. In flight tests with the Avro 707 and early Vulcan prototypes, pilots encountered severe buffet caused by shock-induced flow separation—essentially, the wing was losing lift at high speeds as airflow broke down unpredictably. To mitigate this, engineers at RAE used their state-of-the-art 10-by-7-foot high-speed wind tunnel to conduct a series of detailed tests. These efforts culminated in Technical Memoranda 441, authored in 1955 by RAE aerodynamicist Ken Newby, in collaboration with Avro.

Leading Edge Innovation

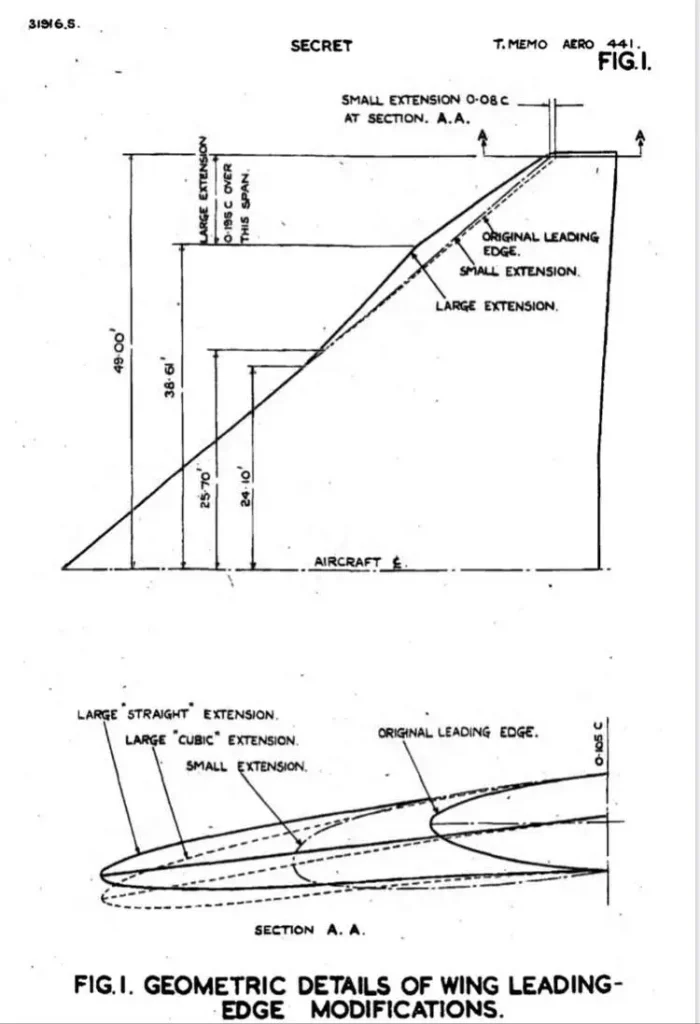

One of the report’s key insights involved modifications to the Vulcan’s wing leading edge. Newby’s research tested three leading-edge designs: a short extension, a long extension, and a curved long extension. The long extension proved most effective. Based on an existing RAE-developed airfoil (RAE 101), it allowed for efficient supersonic airflow expansion, pushing the buffet boundary farther into the flight envelope.

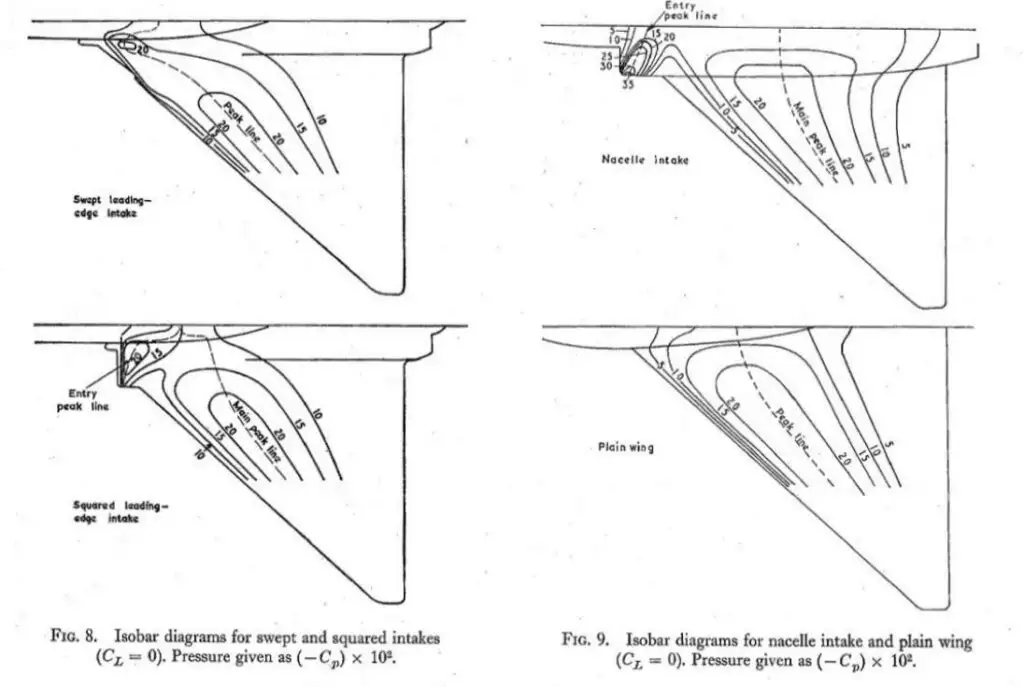

These changes were ultimately integrated into the production aircraft, along with vortex generators placed at 25% chord to energize airflow over the wing. Remarkably, the original Vulcans were built before these aerodynamic refinements were finalized—a testament to the pace at which development occurred and the confidence placed in ongoing research. A comparison with the Gloster Javelin, another aircraft of the era, underscores the Vulcan’s aerodynamic advantage. While the Javelin suffered from poor transonic performance due to unswept isobars across much of its span, the Vulcan’s refined wing and buried engines allowed for a more efficient and stable airflow, giving it a performance edge.

Risk, Reward, and Rivalry

In a move that might surprise modern engineers, some of the Vulcan’s aerodynamic solutions were tested in flight before they were validated in the wind tunnel. Vortex generators were installed on the Avro 707A and flown—a high-risk trial given the state of knowledge at the time. Yet this boldness was characteristic of the era, and of the V-bomber program as a whole. Competition also played a key role. Newby’s report hints at the sense of urgency and national pride that drove engineers to out-design rival firms. Even civil airliner concepts like the Avro Atlantic were tapped for wind tunnel testing in lieu of more accurate Vulcan models, simply to accelerate research timelines.

Honoring Innovation

Though much of this work was once top secret, it now provides a fascinating window into Cold War-era aerospace innovation. The Vulcan, far from being just a striking symbol of nuclear deterrence, was an engineering triumph forged by necessity, collaboration, and creative problem-solving. The aerodynamic breakthroughs achieved by Newby and his team over six decades ago remain a testament to Britain’s ambition to lead in high-performance aircraft design. As Dr. Liddle reflects, honoring this legacy also serves to inspire future generations of engineers pushing the limits, whether in the skies or on the racetrack.

The Vulcan to the Sky Trust is a charitable organization dedicated to preserving two of Britain’s most iconic aircraft—Avro Vulcan XH558 and English Electric Canberra WK163. Both aircraft played pivotal roles in advancing aviation and aerospace engineering. For more information about The Vulcan to the Sky Trust, visit www.vulcantothesky.org