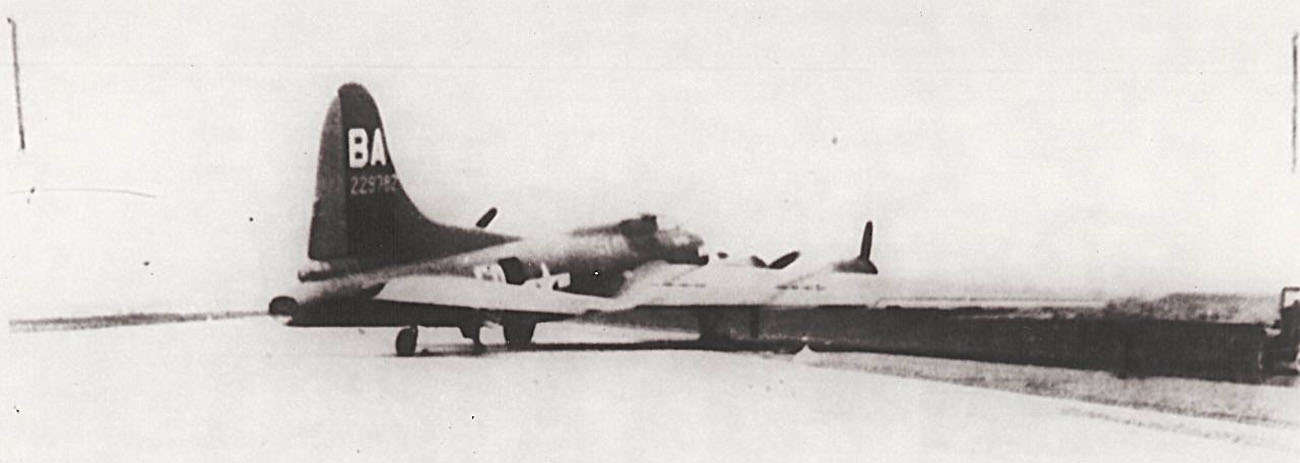

Boeing B-17F Flying Fortress, s/n 42-29782. This particular aircraft was completed at the Boeing Plant 2 south of downtown Seattle, Washington, and accepted by the U.S. Army Air Forces on February 13, 1943 (to protect the plant from possible air attack, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built houses of plywood and fabric and installed fake streets to camouflage the roof). It was immediately flown to the United Air Lines Modification Center at Cheyenne Regional Airport in Wyoming and modified as a TB-17F trainer, and assigned to the 7th Bomb Squadron, 34th Bomb Group at Blythe Field, California (which was training replacement crews for overseas deployment). After about 500 hours of flying time, in May of 1943, it was sent to the Sacramento Air Service Command at McClellan Army Air Base for an overhaul.

On June 15, 1943, it was transferred to the 593rd Squadron, 396th Bomb Group at Moses Lake Army Air Base in Washington state. At least some sources say it was in England sometime between January and March 1944 but did not see combat (one source indicates that the aircraft’s destination was listed as “SOXO” which was the overseas destination code for the 8th Air Force in England and would be listed on the Individual Aircraft Record Card (IARC); and the newer B-17G variants were arriving for combat duty so there is some question as to the purpose of the move to England). It was at Drew Field in Tampa, Florida, with the 396th Bomb Group, and was withdrawn from service on November 5, 1945.

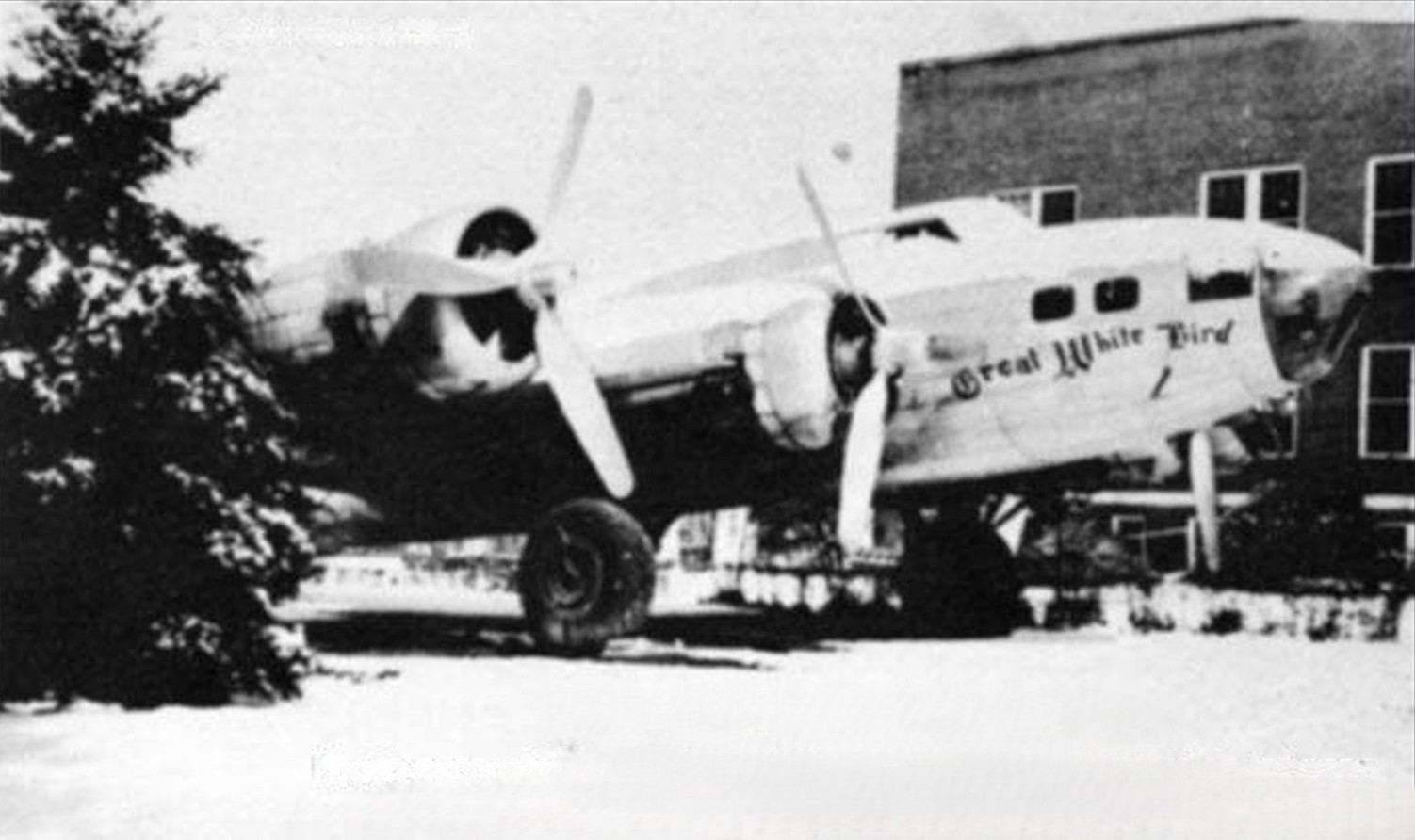

It was then shipped to the federal government’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation’s bone yard at Altus, Oklahoma, for disposal. However, in 1946, stripped of guns and turrets, Pete Moll of Stuttgart, Arkansas, obtained the aircraft for $350 and it was displayed as a war memorial in a park with a natural metal finish so at some point it had been stripped of its standard olive drab and neutral grey paint scheme, and with the nose art “Great White Bird”. But the Stuttgart city government got tired of the display and, though still technically the property of the U.S. government, the city council sold the aircraft to a local man by the name of Gerald C. Frances in 1953, who removed the B-17 from the park.

On April 23 of the same year, the B-17 was again sold, this time to brothers Max and John Bergert for $20,000 and converted to an aerial sprayer (for, among other things, DDT), and on November 25, 1953 it was assigned a new civil registration number of N6015V, but the registration was changed to N17W five months later at the request of the Bergerts. N17W also flew as a fire bomber, and during its 25 year career of firefighting, it wore numerous paint schemes and call signs including E84 (see photo), C84, C44, and 04 (see photo), and appeared in such films as “The Thousand Plane Raid” and “Tora! Tora! Tora!” and the 1989 version of “Memphis Belle” (in that film, it appears as 41-24848, code DP-Y “Kathleen” although it was painted with one scheme on the left side and another scheme on the right side and is reportedly the only genuine B-17F used in filming).

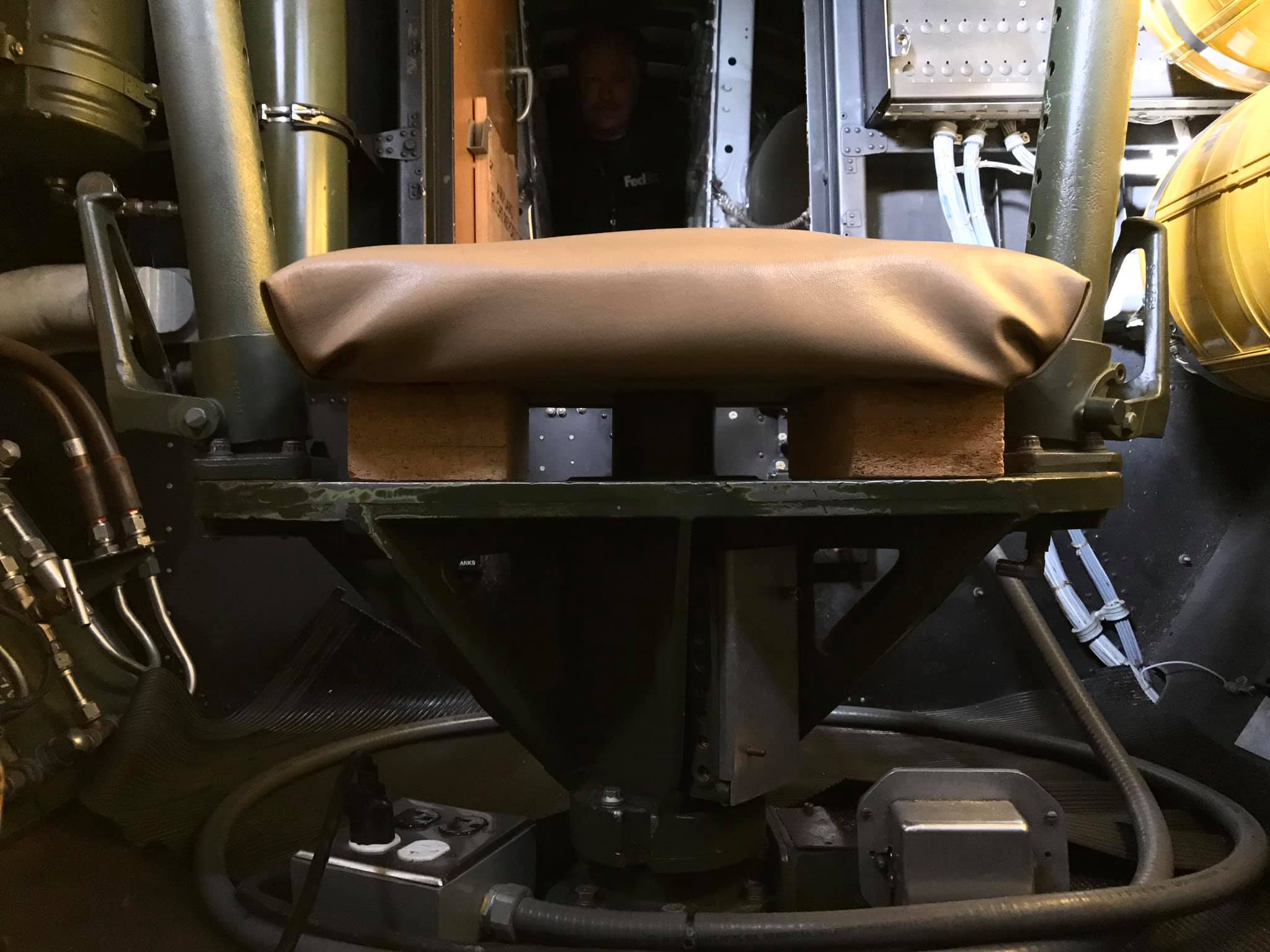

For a time, it was either owned by or leased to Richard “Dick” Baxter of Central Aircraft (formerly Central Airways) in Yakima, Washington (he was a large part of Pacific Northwest small-aircraft history and was instrumental in the origination of the Arlington Air Show in Washington and volunteered his expertise and time over the years to such organizations as the Museum of Flight). Robert “Swage” Richardson of Seattle had purchased the aircraft in 1984-85 and relocated the aircraft to the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington (MOF), where military-style markings were applied over the bare aluminum surface and authentic top turret was added along with a false ball turret; he wanted to give it the nose art “Rain Maker” and had a mock-up made of the design (see photo).

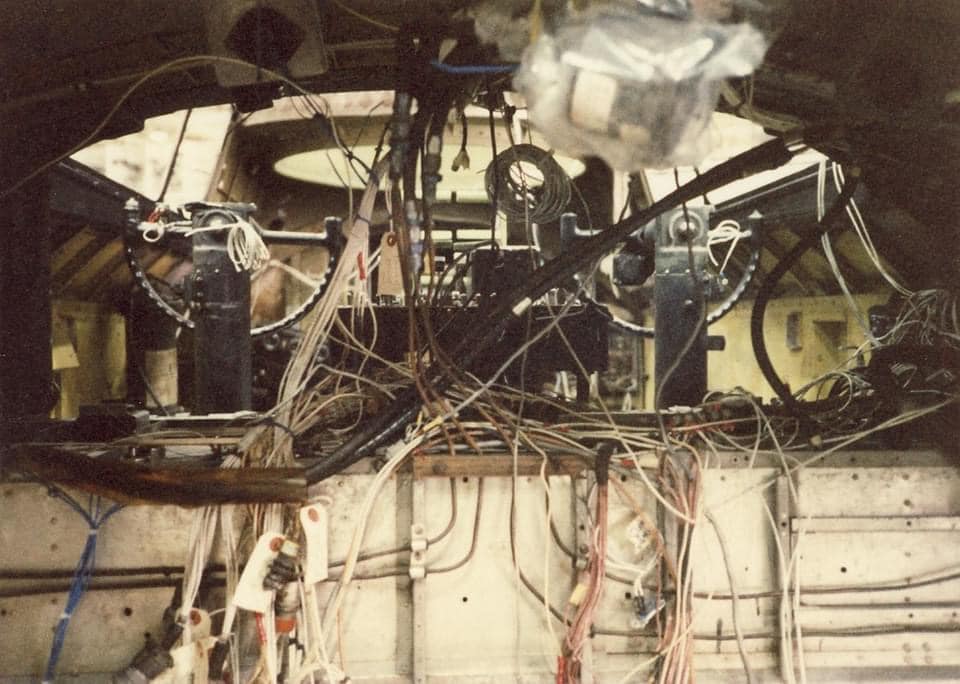

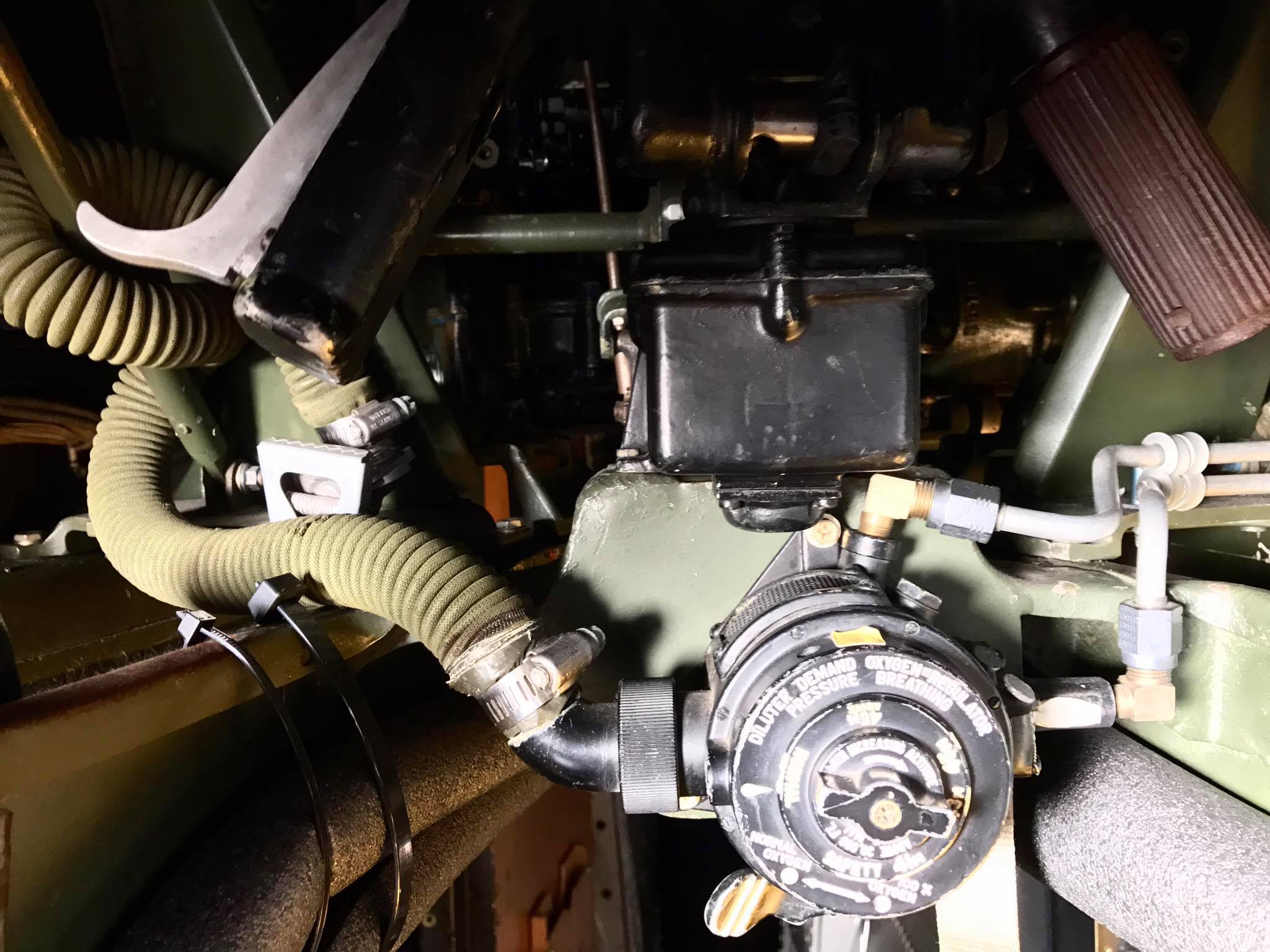

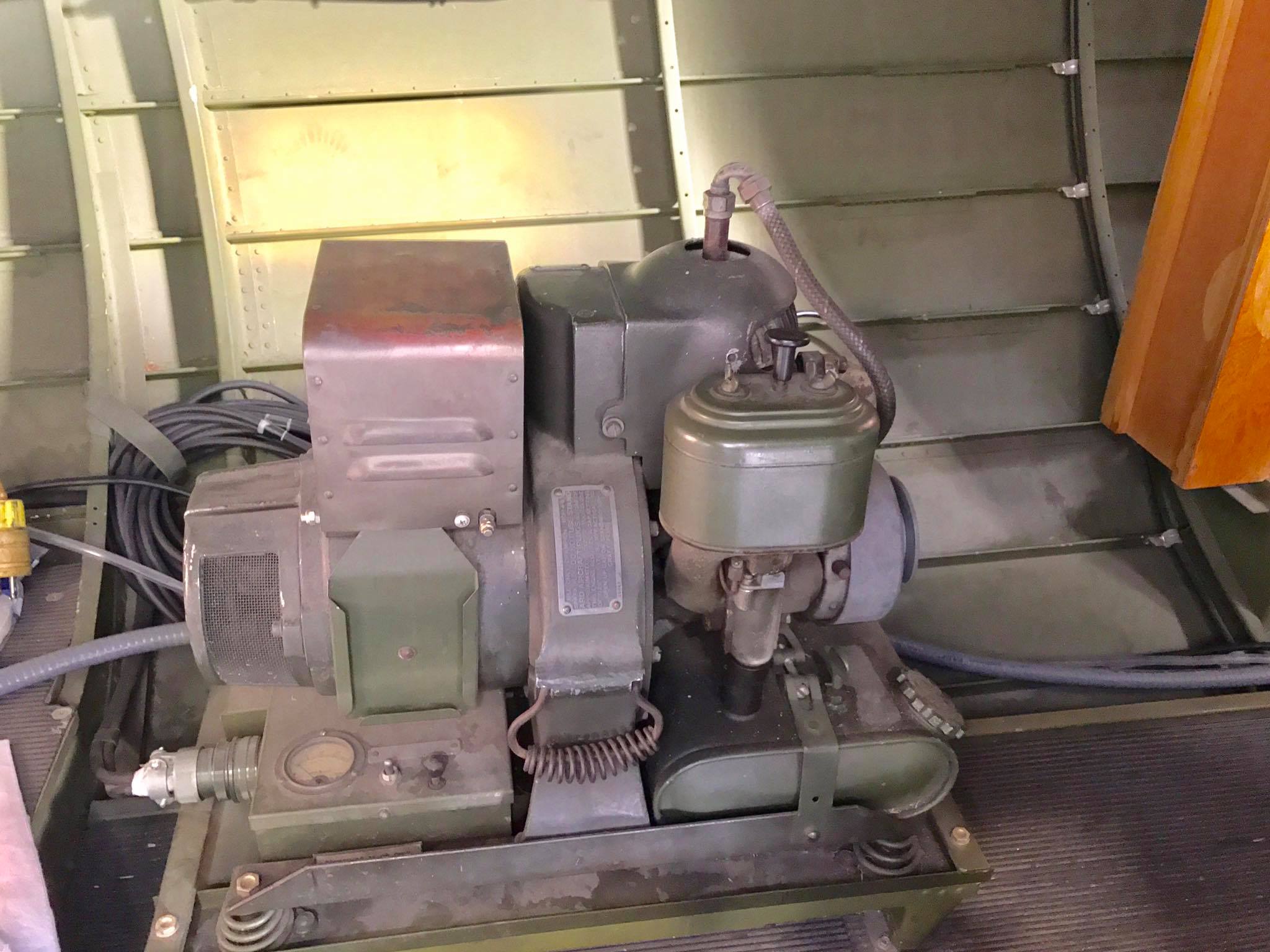

Richardson, at the time the owner of University Swaging Co. (an aircraft components manufacturer and now part of Precision Castparts Corp.’s Engineered Products Division) and well-known for his aircraft restorations, crisscrossed the country flying this aircraft at air shows. He flew the aircraft to England for the filming of “Memphis Belle” in 1989; the aircraft spent some time in Geneseo, New York. In accordance with Richardson’s will, upon his death in 1990, ownership was transferred to the MOF. The MOF Restoration Center began restoration to its current configuration in 1991. Since nearly all the military equipment had been removed from the aircraft during its civilian life (also, bug-spraying chemicals had caused serious corrosion, windows leaked, hoses and oil tanks were cracked and dripping, and holes had been cut into the bulkheads), approximately 98 percent of the original military equipment was reinstalled, and about 95 percent of that is actually operational. It was restored to flying condition and did fly on occasion since its return to Seattle, but will not be flown, as is the case with the collection at MOF.

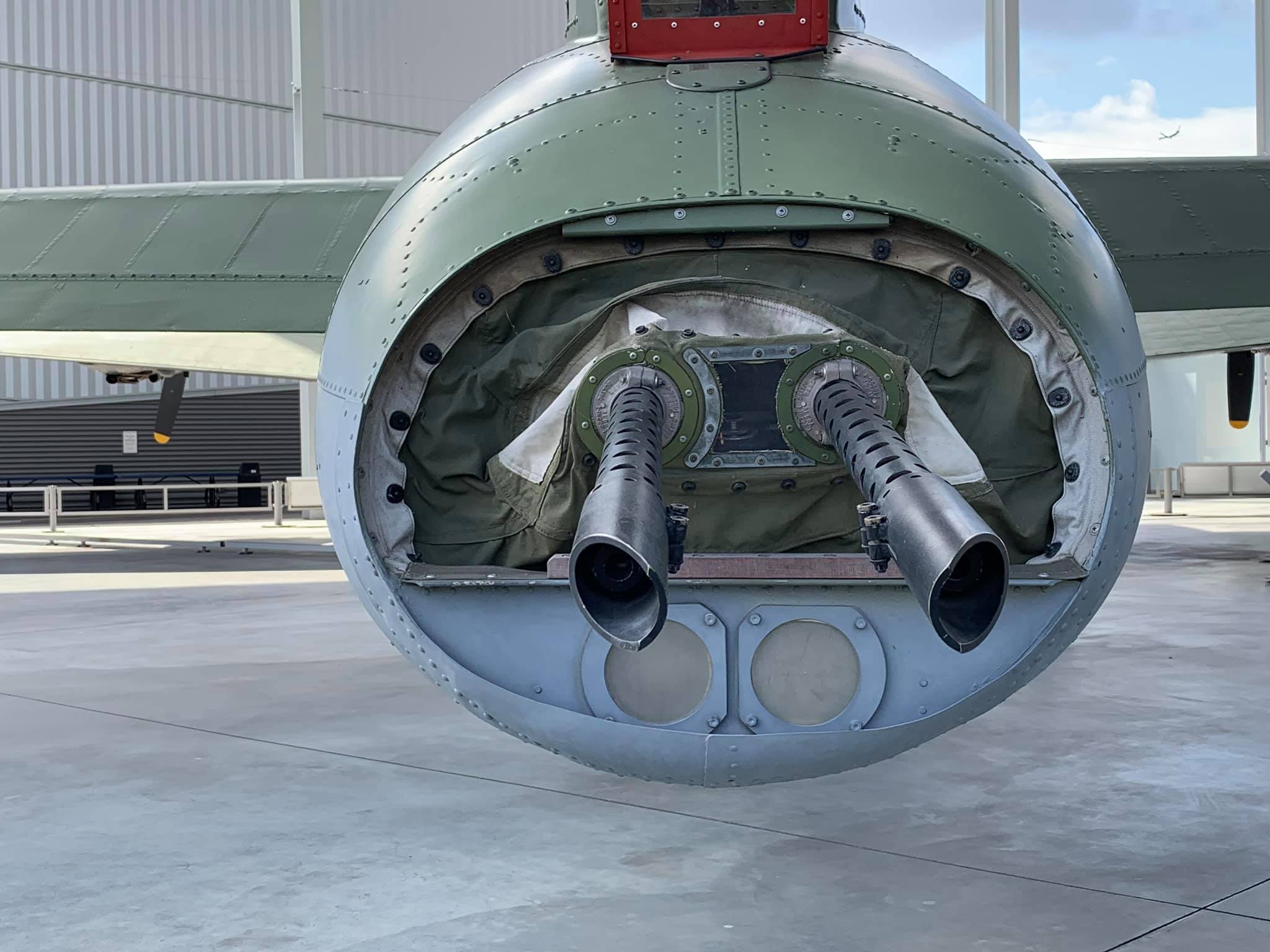

The restoration crew called it “Draggin’ Ass” (and had T-shirts made with the name), but the MOF collectively thought that name or Richardson’s idea for “Rain Maker” were not politically correct for the times. So it was decided to honor all involved with the project and call it “Boeing Bee” based on an old Boeing logo found in the Boeing archives; and ultimately, the word “Bee” was left off the nose art and was done by artist Mick Flynn (see mock-up photos of both nose art designs). The “Steeplechase” or “Stinger” tail turret is painted in honor of S. Sgt. Arthur R. Heino, a tail gunner who flew 33 combat missions between 1944-45 with the 94th Bomb Group in England (Heino, a Finnish-American, also served as a fighter plane crew chief, played trombone, and became a master potter and died in 2009).

The dorsal turret is painted in honor of T. Sgt. Ralph McLaren, also of the 94th Bomb Group. Among other things, it is restored with an authentic Browning .50 cal. machine guns (demilitarized, of course); a trailing antenna spool, mast, and avocado weight; a crew relief tube; a top turret with a gunner’s platform; and the ball turret equipped with a K-4 computing sight; the red box around the stinger tail turret’s gunsight is to keep the gunsight from being damaged or stolen. Also fitted with 1936 Ford ashtrays at some crew positions. As of this writing, the MOF is or was looking for the proper materials to paint the skin in a more authentic color scheme and paint materials befitting the period of its operations being represented (and of course, different compounds were used on the fabric control surfaces). I also understand some take exception to the fact that the interior is not left largely unpainted with quilted fabric padding in the crew compartments.

The Norden bombsight was found in an Iowa State University warehouse by a friend of engineer Paul Nelson (Nelson’s first job was as a NASA engineer and helped perfect the Saturn V moon rocket for the Apollo missions). Nelson bought it for $5, completely restored it, and then donated it to the Museum of Flight. The aircraft is listed as FAA airworthy, but my understanding is that “static display” does not require modern avionics, but it may have what is required to fly. My photos, along with a few courtesy of Don England, thanks. The “Flying Fortress” nickname was coined by Richard L. Williams, a writer and editor for the Seattle Times, when he was assigned to write a caption on a photo of the Model 299, a prototype that was unveiled at Boeing on July 17, 1935.

The F models were generally armed with Browning M2 .50 caliber twin-mounted machine guns in the Sperry A-1A dome dorsal turret; twin-mounted in the lower Sperry ball turret (with a K-4 computing sight); one aft-facing in the radio room (either fixed or on a sliding track); single-mounts in the left and right waist positions (in the later G model, they were enclosed in Plexiglas and were staggered); and twin-mounted in the “Steeplechase” or “Stinger” tail gun with just a ring-and-post sight (that was later replaced with the Cheyenne turret – named after the United Airlines Cheyenne Modification Center in Cheyenne, Wyoming – that had a hand-rotated “pumpkin” mount and had better visibility).

An initial single .30 cal. in the nosecone proved inadequate against frontal attacks, and it was replaced by .50 cal. cheek-mounted guns (there was some creativity in field modifications, and this aircraft appears to have such a field modification .50 cal. for the navigator on the port side of the nose; but the pair became more or less standard and were fired by the navigator and/or bombardier/gunner). It could carry between 4,500 and 8,000 lbs. of bombs, depending on the distance to the target and the type of mission. The bomb camera is located under the floor of the radio room (see photos). Electrical power is supplied by a 24-volt DC system, which distributes power from four engine-driven generators and from three storage batteries in the leading edges of the wing just outboard of the fuselage.

Related Articles

Raised in Fullerton, California, Adam has earned a Bachelor's degree in History and is now pursuing a Master's in the same field. Fascinated by aviation history from a young age, he has visited numerous air museums across the United States, including the National Air and Space Museum and the San Diego Air and Space Museum. He volunteers at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino as a docent and researcher, gaining hands-on experience with aircraft maintenance. Known for his encyclopedic knowledge of aviation history, he is particularly interested in the stories of individual aircraft and their postwar journeys. Active in online aviation communities, he shares his work widely and seeks further opportunities in the field.