At Duxford Airfield in Cambridgeshire—the beating heart of British vintage aircraft flying—the whine and roar of Rolls-Royce Merlin engines marked the 85th anniversary of the start of the Battle of Britain (10 July–31 October 1940). On 6 July, against a dramatic backdrop of storm clouds, a flying display featured Supermarine Spitfire Mk Ia, Mk XVI, and Hawker Hurricane Mk I fighters. The main commemorative air show will take place at Duxford on 6–7 September. As always at this historic site—home to the Imperial War Museum’s world-renowned aircraft collection—aviation enthusiasts from around the globe will gather to witness the iconic warbirds wheeling in formation and engaging in mock dogfights above the airfield.

The Battle of Britain Memorial Flight (BBMF), operating Spitfires, Hurricanes, an Avro Lancaster, and a C-47 Dakota from RAF Coningsby in Lincolnshire, will participate. The BBMF resumed flying in May following a temporary stand-down after the tragic crash of a Spitfire Mk IX on 25 May 2024. Elsewhere, anniversary events are also planned at key former RAF fighter stations in southern England—sites that played crucial roles in defeating the Luftwaffe during the summer and autumn of 1940. These include the former RAF Fighter Command HQ at Bentley Priory (Stanmore, London), RAF Group No.11 HQ at Uxbridge, RAF Biggin Hill in Kent (home to six operational Spitfire squadrons during the Battle), and the RAF Museum in Hendon.

Eighty-five years on, the generation who fought the Battle has all but passed. In March, the last surviving RAF Hurricane pilot, Group Captain John ‘Paddy’ Hemingway DFC, died at the age of 105. Yet the Battle of Britain remains a defining chapter in British and Allied memory. It was a life-or-death struggle for control of the skies above southern England. For Britain, national survival hung in the balance.

The Battle Begins

Following the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939, eight months of relative calm—the “Phoney War”—ended abruptly with Germany’s swift and devastating victories across Europe in the spring of 1940. The British Army was forced to retreat to Dunkirk and evacuate during Operation Dynamo (26 May–4 June 1940). After France fell in June, newly appointed Prime Minister Winston Churchill rallied the British people. Hitler, hoping to force a peace settlement, launched an air and sea blockade. In July 1940, Luftwaffe dive bombers, including Junkers Ju 87 Stukas and Ju 88s, began targeting British merchant shipping in the English Channel, sinking over 30,000 tons of vessels in a single month. Ports, supply depots, and aircraft factories soon came under attack.

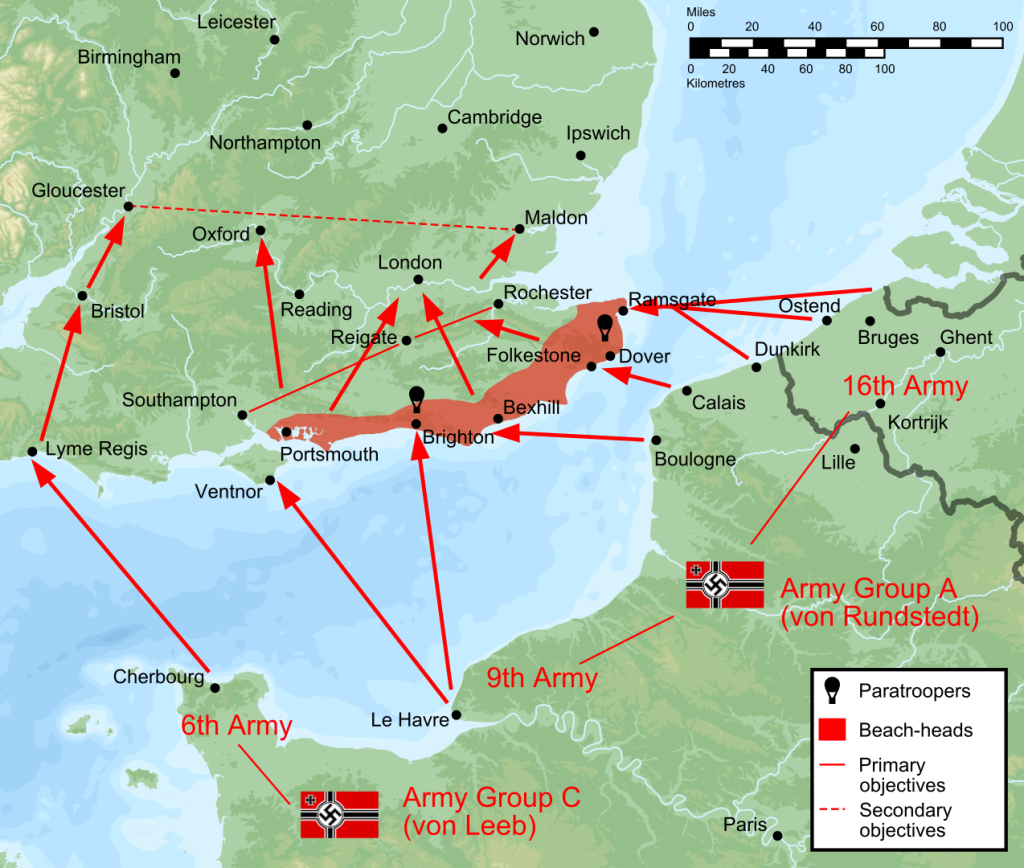

At Hitler’s direction, plans for a full-scale invasion of Britain—Operation Sea Lion—were drawn up. But the strategy relied entirely on gaining air superiority. Hitler’s Air Minister and Luftwaffe commander, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, was tasked with destroying the RAF ahead of the planned invasion, scheduled for mid-September. Göring believed the RAF could be defeated in just four weeks.

The Luftwaffe Offensive

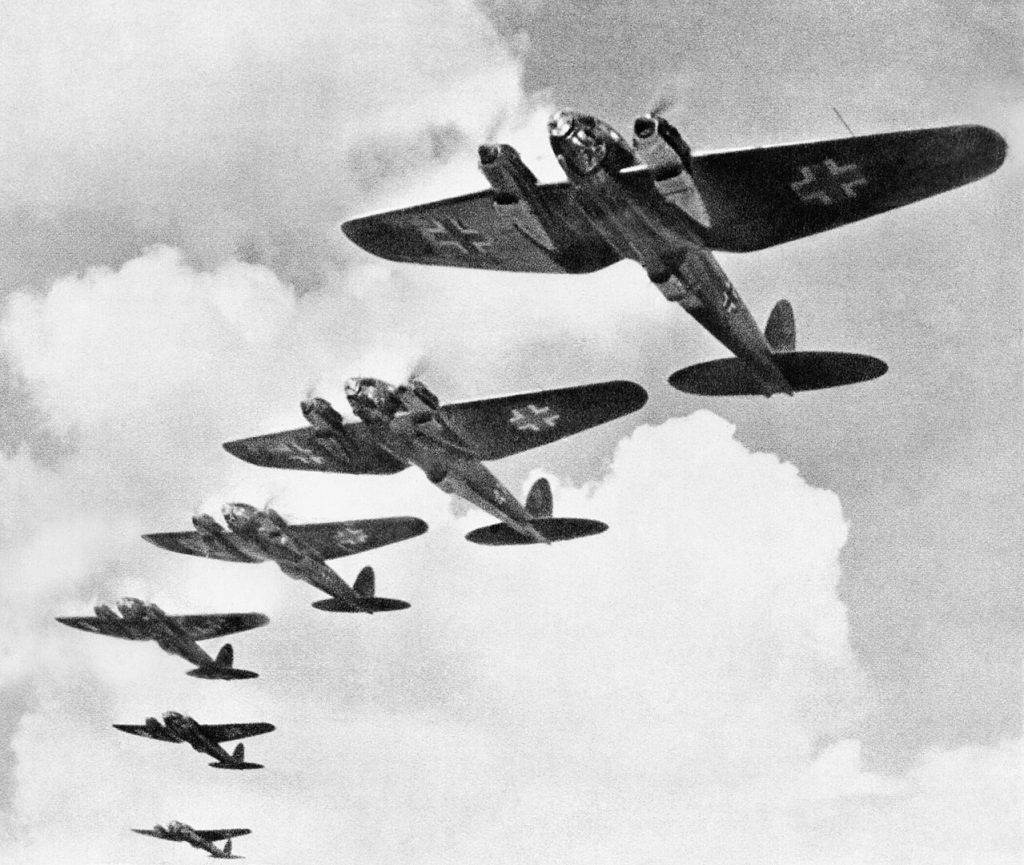

From airfields in occupied France, Luftwaffe aircraft could reach Dover in just six minutes. Göring launched a massive air campaign involving 2,500 aircraft, including waves of Heinkel He 111s, Dornier Do 215s and Do 217s, Junkers Ju 88s, and Ju 87 dive bombers, escorted by 1,000 Messerschmitt Bf 109s and Bf 110s. High-altitude Junkers Ju 86P bombers, equipped with pressurized cabins, were deployed for reconnaissance missions up to 40,000 feet. The Luftwaffe’s objective in July and August was to wipe out the RAF’s airfields and its outnumbered force of Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires. Despite intense and often effective bombing raids, the Luftwaffe failed to gain control of the skies. By mid-September, the momentum shifted.

RAF Endures, Then Prevails

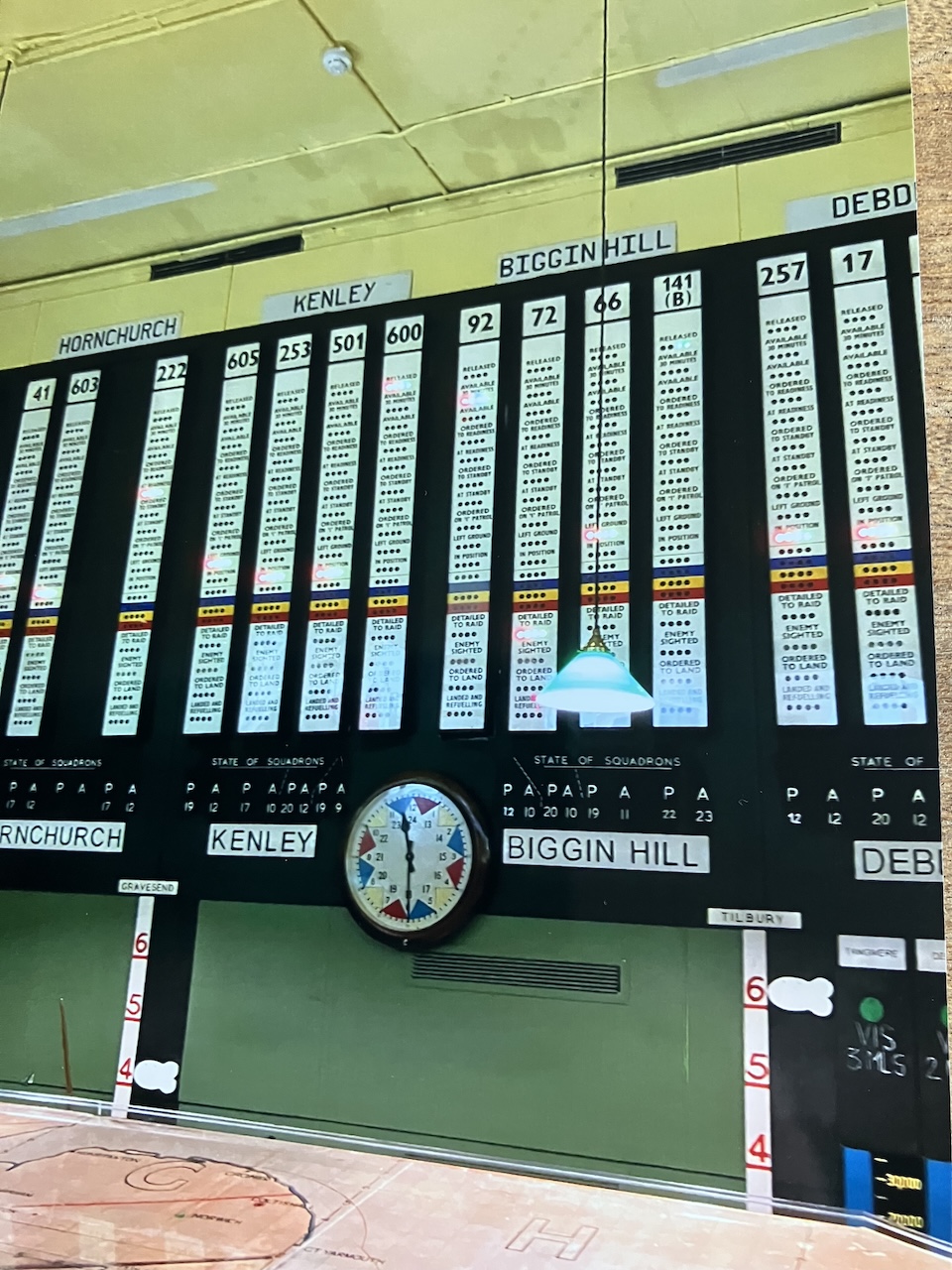

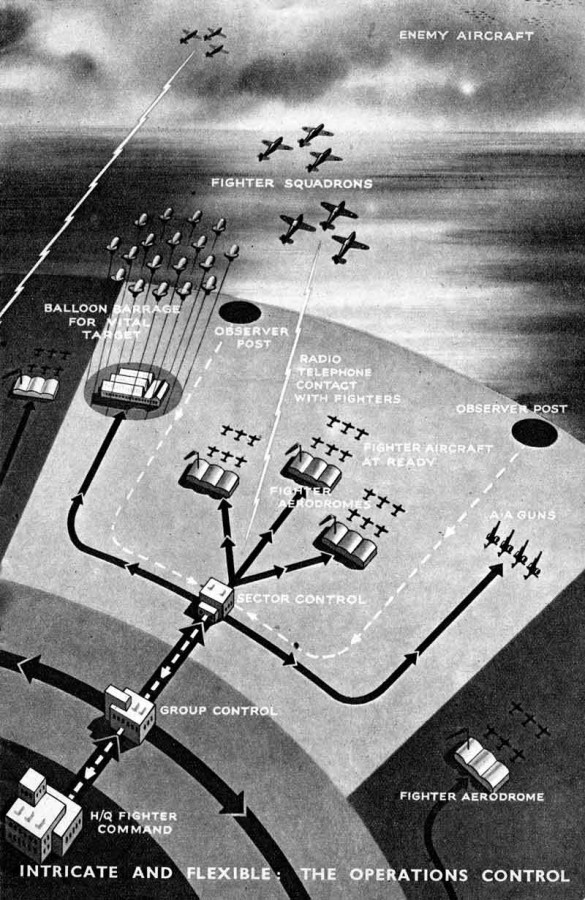

Britain’s survival depended on a revolutionary air defense system developed by Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding and Air Vice Marshal Keith Park. This “Dowding System” integrated 21 ‘Home Chain’ radar stations, the Royal Observer Corps, radio monitoring, acoustic detection, and centralized command centers. Radar coverage detected incoming enemy aircraft up to 100 miles away. This information was relayed to Fighter Command HQ at Bentley Priory in North London, where the underground Filter and Operations Rooms identified and plotted enemy formations. Orders then moved through Group HQs to alert squadrons. RAF No.11 Group at RAF Uxbridge was the nerve center of operations in southeast England, directing fighters from airfields across the region.

Guided by this system, around 600 Hurricanes and Spitfires from No.11 and No.12 Groups fought to intercept the Luftwaffe. Shortages of trained pilots made the effort especially daunting—many were just 20 years old with two weeks of flight training. Fortunately, volunteers from across the world soon bolstered RAF ranks, including 146 Poles, 88 Czechs, 29 Belgians, 13 French, 11 Americans, 10 Irish, and one Austrian.

Yet Britain had key advantages. RAF fighters operated over home territory, allowing rapid refueling and rearming. Radar allowed aircraft to be scrambled only when needed—eliminating costly patrols. Damaged airfields were bypassed with temporary satellite fields. Crucially, German intelligence consistently overestimated RAF losses and underestimated British aircraft production. From June to October 1940, Britain produced around 2,000 fighters—outpacing Nazi Germany. Luftwaffe tactics, meanwhile, faltered. Göring’s order for Bf 109s to slow down and stay close to bombers limited their effectiveness. With fuel for only 30 minutes over southern England—and just 10 minutes over London—German fighters couldn’t dominate the battlefield.

Turning Point

In late August, Luftwaffe raids moved closer to London. After mistakenly bombing central London on 24 August, the RAF retaliated by striking Berlin. Hitler, enraged, ordered a full shift to bombing British cities. On 7 September, the Luftwaffe began targeting London in earnest, inadvertently easing pressure on RAF airfields. This marked the beginning of the Blitz and a new phase in Britain’s wartime experience.

The pivotal moment came on 15 September 1940. In a massive air battle over London and the southeast, 28 RAF squadrons inflicted heavy losses—56 German aircraft were shot down for 26 RAF fighters lost. Churchill, observing operations at RAF Uxbridge, later wrote: “We must take 15 September as the culminating date” of the Battle. Air combat continued into late October. As RAF interception rates rose, the Luftwaffe abandoned daylight raids in favor of night bombing.

Victory and Legacy

The Battle of Britain marked the first major defeat for Nazi Germany. With no air superiority and insufficient naval strength, Hitler postponed Operation Sea Lion on 17 September and canceled it on 12 October. The RAF had won a crucial defensive victory. Though far from easy, they held the line. Of the 2,945 British, Commonwealth, and Allied aircrew who flew during the battle, 544 were killed, along with 312 ground crew. The RAF lost 915 aircraft. German losses totaled 2,662 aircrew killed and 1,773 aircraft destroyed.

As the 85th anniversary is commemorated this summer, aviation fans can witness the legacy of the Battle of Britain firsthand. In addition to the air displays at Duxford, key sites such as Bentley Priory Museum, the Battle of Britain Bunker Museum at Uxbridge, and Biggin Hill’s Museum and Chapel offer a direct connection to this critical period. These places remain steeped in atmosphere and serve as lasting reminders of one of the Second World War’s most pivotal moments. Image via Wikipedia