By Austin Hancock

Aircraft of WWII have a certain draw; they tend to pull people in. I am convinced that they are magnetic, as at every airshow I attend, these “warbirds” attract aviation fans and pilots alike. If you were to ask most any pilot what their dream machine would be, the answer would likely be that of some type of classic warplane – such as the P-51 Mustang, F4U Corsair, or Supermarine Spitfire. Few people are fortunate enough to officially become aviators, and even fewer have the honor of flying these historic fighting machines. Lofty a goal as it may seem, having the right work ethic, mindset, and personality can help make this aviation dream a reality. Chasing this dream all starts with a single step. In past articles, I have made mention of the “words of wisdom” once bestowed upon me by noted warbird pilot Doug Rozendaal. Rozie – as so many of us call him – is a well-respected aviator and a great mentor. He has influenced many aspiring pilots to take the steps toward achieving their dreams of flight. I am lucky to have been one of these young pilot wannabees. In 2010, Doug flew the Commemorative Air Force’s Red-Tail P-51C By Request to the Geneseo Airshow for a weekend of performance aviating. He and I had chatted a bit online, but it was at Geneseo when I finally had the chance to meet and talk with Doug face-to-face. He asked me about my goals as an aspiring professional and warbird pilot, and listened to everything I had to say – every little hairbrained goal. Many would laugh at a young high-schooler with such ambitious and resource-dependent goals, but not Doug.

With his calming and confident voice, Doug asked me a question – “How do you eat an elephant, Austin?” I was a bit shocked by the hypothetical situation; teens tend to take things rather literally. So, as I sat there with an inquisitive look on my face (and the gears turning in my head, “how would I eat an elephant?”) Doug followed up by answering, “one bite at a time.” Suddenly, it all made sense. The largest, most lofty and ambitious goals are possible, but they require time and dedication to be realized. In the years that immediately followed our talk, I’d go on to attend college and flight school, while working full-time. I graduated, then earned my commercial pilot and certified flight instructor certificates. I currently work as a CFI, building my flight experience and hours with an aim to fly professionally. I also have the privilege of taking the first few bites of the warbird flying elephant – thanks to the National Warplane Museum’s Aeronca L-16A.

The story of the L-16 begins on April 29, 1944. It was on this date that the Aeronca Model 7 Champion, or Champ for short, first took flight. The production Aeronca 7AC Champ entered production in 1945, with the aim to best the Piper J-3 Cub in overall performance and comfort. 7ACs sold well, primarily to flight schools that were doing good business – a result of an influx of students from the G.I. Bill. Sales of the Champ peaked in 1946, and during this year, Aeronca was producing an average of 30 7ACs per month. The post-war boom soon tapered off, and demand for light airplanes trailed off in the later 40s and early 50s. Fortunate timing would help keep Aeronca’s Champ relevant and in demand. The advent of the Korean War presented a need for a light liaison and observation aircraft – and the Champ was a perfect candidate for the job. Born from this wartime demand was the Aeronca L-16, a militarized version of Aeronca’s 7AC.

Aeronca’s L-16 was derived directly from the Champion Model 7 Series. Two variants of the military Champ were built, the L-16A and L-16B models. The L-16A was powered by an 85-horsepower C85 Continental O-190-1 flat-four engine; 509 were built. L-16Bs used the 90-horsepower C90 Continental O-205-1 flat-four engine; 100 B-models were manufactured. The L-16 offered increased performance, more stable flight characteristics, and enhanced visibility and comfort over the Piper L-4. Overall, the safety of the L-16 was mixed in comparison to the L-4, but regardless, the military Champ ended up replacing the Piper Grasshopper in U.S. military service.

The C90-powered L-16B model had a crew of two – pilot and radio operator/observer. In combat, this duo would work as a team to spot enemy positions – relaying the coordinates back to the artillery for “clean up.” The L-16B had a maximum speed of 110 miles per hour, but would typically cruise at 100. The aircraft had an empty weight of 890 pounds and a max gross of 1,450. Factoring in crew, fuel, and supplies, there was not much wiggle room for weight and balance. L-16s had a range of 300 nautical miles, and a service ceiling of 14,500 feet – though liaison missions typically saw the aircraft operating at tree-top level. The military Champ was unarmed, with the exception of the handguns and marking flares carried by the crew. During the Korean War, the L-16 was flown by the United States Army, the National Guard, and the Civil Air Patrol.

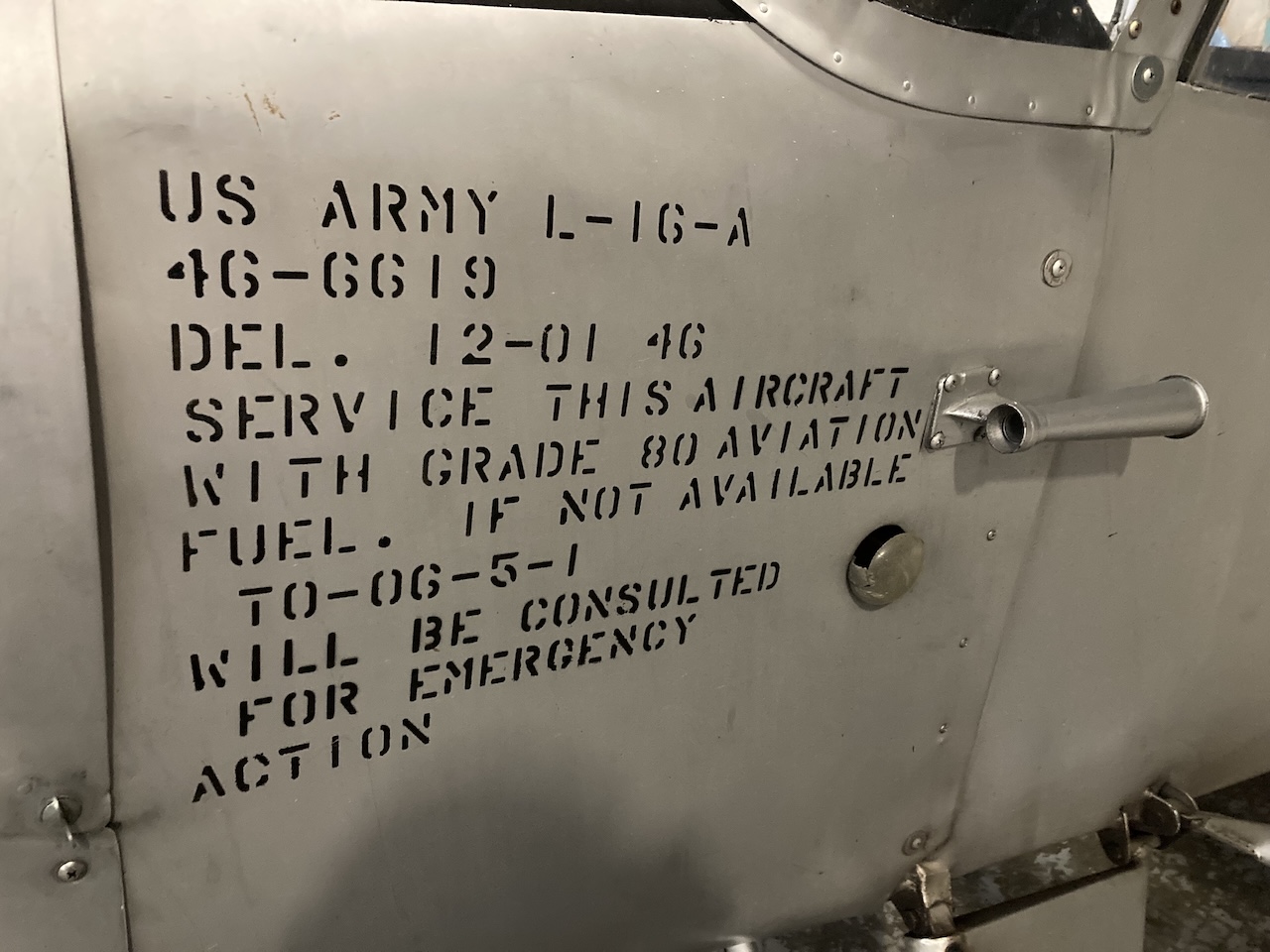

The National Warplane Museum – in Geneseo, New York – is home to Aeronca Champion 7AC-6619, N3033E. Built in 1946 as a 7AC model, this Champ was restored into an L-16A model in the early 00s. During those days, the museum was known as the 1941 Historical Aircraft Group. A team of members within the organization pooled resources to acquire and restore the aircraft. 7AC-6619 retains the original 65-horsepower Continental A65-8 engine, slightly less than the military versions. Despite the difference in powerplant, Geneseo’s L-16 still looks the part. During restoration, the rounded rear windows were replaced with the greenhouse canopy found in Korean War models. 7AC-6619 was given a military paint job and flies as a New York Air National Guard bird. The Geneseo L-16 flies routinely and is a well-adored member of the museum’s aircraft fleet.

L-Birds, such as the Aeronca L-16, Piper L-4, and Taylorcraft L-2,are the perfect entry point for aspiring warbird pilots for many reasons. These aircraft are often more affordable, both to acquire and operate. The barrier to entry is low, and these light taildraggers are the ideal platform for learning the essentials of tailwheel flying. This is not to say that they are simple to fly, rather they are great aircraft for learning the fundamentals. I’ve heard many current heavy-iron warbirders say that “if you can fly a Champ, you can fly any warbird.” Flying higher-performance warplanes isn’t quite that simple, but the main idea is that the fundamentals go a long way towards flying faster and more complex vintage fighting machines.

The L-16 is an honest flying machine. Pre-flight is a relatively straightforward process; you inspect items just as you would on a Cessna 172 or other similar single-engined trainer. Starting the L-16 is done the “old-school” way, as Geneseo’s Champ does not have an electrical system – meaning no starter. After a few shots of prime and four blades of pull-through, N3033E usually starts up with no hesitation (keyword, “usually,” sometimes she doesn’t start easily!) As you begin to taxi, you realize that the visibility over the nose is perfect – there is no need to fishtail the aircraft to find your way to the runway. While flying the AT-6 last year at Warbird Adventures, I learned that s-turns are a good skill to master. Even though I can see over the Champ’s nose just fine, I still do a few fishtails each time I taxi out and back – it keeps the skills sharp for when “the time” comes.

Flying a taildragger requires prudent and frequent use of the rudders. For any tailwheel student, this can take a few hours to develop a touch for. Eventually, the aviator develops a feeling of synchronicity with their taildragger. At this point, the plane and the pilot work together as one. Taxiing requires a fine touch on the rudders, as does takeoff. With the L-16, takeoff begins with the stick back and into the wind (if any exists…who am I kidding…it always exists!) You smoothly apply power – pretending you’re throttling up a P-51. Gauges green, airspeed alive, stick forward to get the tail up while maintaining directional control with the rudders. At 48 mph, the L-16 gets airborne. Once you’re off the ground, you pitch for Vy, which is 65 mph. In the L-16 as a 6’1” tall pilot, the pitch attitude for this climb airspeed places the base of the gas cap right on the horizon of the Genesee Valley. This aircraft does not climb fast, but I see it as more time to enjoy the ride. Time to level off and do some Champ maneuvers. You bring the power back to 2100 rpm, and re-trim using the control over your left shoulder. In cruise, the 65 hp L-16 will attain 80 to 85 miles per hour indicated. At this power and airspeed combo, I have found the fuel burn to range between 3.5 and 4 gallons per hour. When I fly the L-16, I always warm up with some dutch rolls – rolling the airplane side to side while coordinating rudder inputs to keep a spot on the horizon. The aircraft maintains coordination very well when correct control inputs are used. These inputs are often very minimal and slight, but require finesse. After a couple of clearing turns, I will test out my steep turn skills. The L-16 loves to steep turn, as long as you keep the rudder centered. An extra 100 rpm, and a hint of up-trim, while entering the turn, will help maintain altitude.

Power-off stalls in the L-16 are very calm. Just as with all the previous and future maneuvers in the Champ, rudder coordination is key. If you stay “on the ball,” the aircraft will simply relax its nose-up attitude once the critical angle of attack is exceeded. Let the nose come down, add power while turning off carb-heat, and recover. Power-on stalls are much the same, only the stall takes a bit longer to happen, and it’s even less noticeable unless you are looking at your airspeed and altitude. Recovery is simple; let the nose come down, and then recover your altitude. We’ve had enough fun in the air for today. Let’s head back to D52.

You plan your descent and enter the 1,600’ pattern at Geneseo around 70 mph. On downwind, I pull the power back to 1500 rpm and apply the carb-heat. There is no VSI on the gauge cluster, but this power setting provides a stable descent as you round from downwind to base to final. A quick T-GUMPS check on final…Trim: Set, Gas: On, Undercarriage: Welded, Mixture: N/A, Prop: N/A, Switches: N/A – simple! I will peg 60 mph on the airspeed indicator and fly right down to the ground. Most times, coming in over the trees on runway 5, I will use the forward slip to bleed off altitude. The L-16 loves to slip, and does so very effectively. From time to time, I may need to add a twinge of lower to slow the rate of descent. Most times, however, the L-16 will fly power-off from short final to touchdown. In ground effect, the Champ likes to float – so patience is key. You just keep holding the plane off until the faithful little L-Bird has decided it has had enough flying for one day. The L-16 will settle in a nice three-point landing attitude.

The touchdown is only the beginning – remember, this is a taildragger. Once all three wheels are down, immediately bring that stick back – while keeping in any wind correction with the ailerons. At the same time, maintain directional control with the rudders, which will require greater control inputs as airflow is reduced over the control surfaces. Many wise warbird pilots have told me that you don’t stop flying a taildragger until it is parked in the hangar, and that is a wise bit of advice to live by. As you taxi back to the hangar, practicing your fishtailing, a big grin breaks out on your face. The L-16 brings joy and achievement to those who fly it, and a sense of excitement about the future flying possibilities that lie ahead.

The Aeronca L-16, as with all L-Birds, is a great motivator for those who want to fly warbirds. These aircraft provide just enough of a taste of warbirding to keep pilots chasing their dream. When I first earned my tailwheel endorsement a few years ago, my instructor and fellow Geneseo pilot Rob Gillman gave me a wise bit of advice. ”Don’t quit. Even when you’re the number one guy, you have to act like you’re the number two guy trying to get there.” These words have always stuck with me. There are ups and downs in life, unpredictable curveballs that are thrown your way. Those who see through the challenges and continue to push are the ones who meet their dreams. I am forever grateful to Doug, Rob, Pete, Thom, Wes, and countless other warbird pilots who have given me the tools to chase this dream of mine.

I continue to fly the National Warplane Museum’s L-16, enjoying the ride. You cannot rush the achievement of dreams and goals, but you can do everything in your power to give yourself the best odds. Right now, I am enjoying every single moment of Champ flying, reinforcing the fundamentals of tailwheel flying within myself. I am thankful to the museum for the opportunity, and for any that may be on the horizon. Geneseo is a great starting point. I will be continuing to branch out to other warbird opportunities this winter and beyond. I envision the day when I will be flying a P-51, telling the story of Tuskegee Airman F/O Leland Pennington and countless others at each event I fly in. Whether this occurs in Lucy Gal or another outfit’s Mustang, I will not quit chasing my dream of keeping the legacy of these aircraft and the people who flew them alive. I am forever grateful to my Geneseo family, Doug, Thom, Wes, and countless other warbird pilots who have given me the tools to chase this dream of mine.