Some fighter pilots are remembered because they led squadrons to victory, others because they shaped airpower doctrine. But a few are remembered because of the way they fought and survived despite the fact that the chances were negligible. Captain Alexander Beck, a flying ace, belonged to the last group, going to World War I before he could truly be called a man, and learned to fight in one of the most dangerous skies in history.

Beck was born on November 3, 1899, in Argentina, to English parents who had moved abroad for work, and like many young men of his generation, he felt the pull of the war in Europe long before it made any sense for him to answer it. Sent to England to study, he did something far more dangerous instead, lying about his age and joining the Royal Flying Corps while at just 17 years old, at a time when flying itself was as deadly as combat. By the summer of 1917, Beck had completed his training and found himself posted to No. 60 Squadron, flying the Royal Aircraft Factory S.E.5a, one of Britain’s best fighters of the war.

Alexander Beck: Rise of a Flying Ace

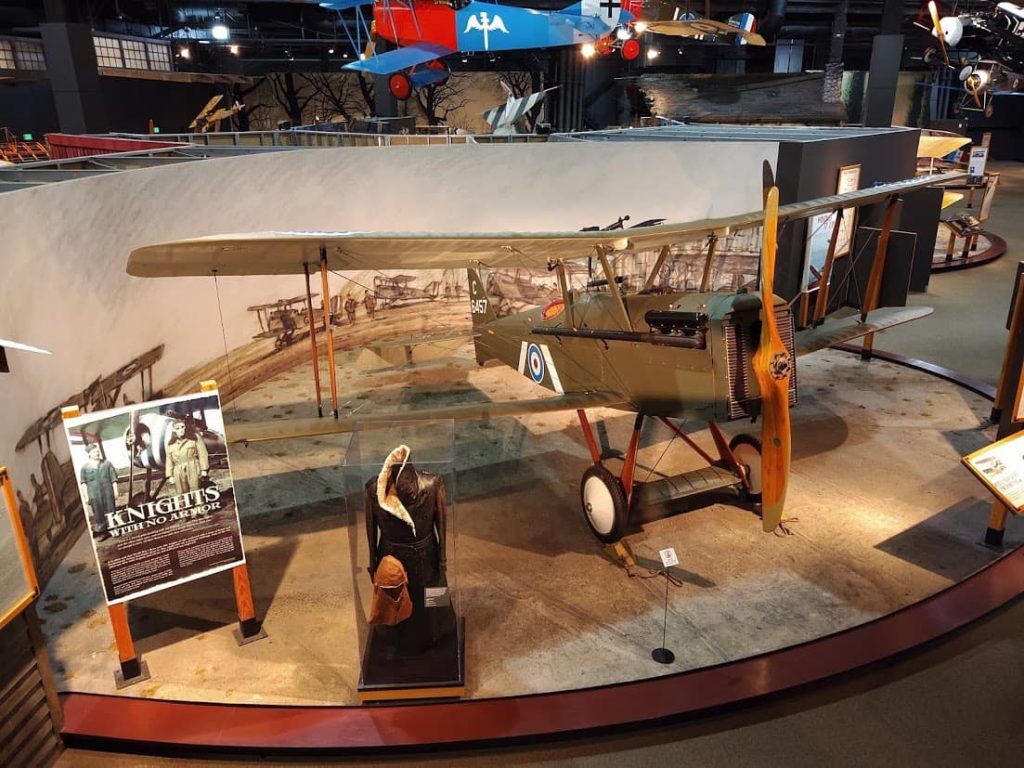

The S.E.5a was not a forgiving aircraft, but it was fast for its time, capable of reaching around 120 mph at 15,000 feet, powered by a Hispano-Suiza V8 engine, and armed with a synchronized .303 Vickers machine gun and a .303in Lewis gun mounted above the wing. In the hands of an experienced pilot, it was stable and deadly, and Beck learned to fly it over the most dangerous airspace in the world, the Western Front. Before his parents even realized where he was, he had already flown 13 combat sorties over enemy territory, dodging anti-aircraft fire and German fighters, and gaining experience no classroom could teach. When his parents found out the truth, they informed the authorities that Beck was still a minor. As a result, he was pulled out of France and abruptly sent home, but it did not lower his determination. As soon as he turned 18, in early 1918, he returned to 60 Squadron, this time legally, and now with the confidence of someone who already knew what combat felt like. The air war had intensified by then, with the Germans fielding new fighters such as the Fokker D.VII, widely regarded as one of the best aircraft of the conflict. The skies over France were crowded with several dogfights.

Beck’s rise from a capable pilot to a fighter ace began on August 8, 1918, when he shot down a German Fokker D.VII over Folies Rosières. Just a few days later, on August 14, he struck down a German Hannover reconnaissance aircraft during an early morning patrol over Riencourt. The same evening, he returned to the skies and shot down another German fighter, an Albatros D.V, near Guemappe. As Allied forces launched the Hundred Days Offensive from August 8 to November 11, a decisive series of offensives that broke the German army on the Western Front, Beck continued to attack heavily defended two-seater reconnaissance aircraft that were critical to German operations. On August 31, he shot down an LVG C-type reconnaissance aircraft near Inchy. As he downed another LVG over Cambrai on September 28, he officially became a flying ace, a title reserved for pilots with five confirmed kills.

The October Surge

Beck, who was already a flying ace with five confirmed kills, hunted five more aircraft in just one month of October 1918, showing the level of confidence and self-belief he had at the time. He shot down a Fokker D.VII over Esnes on October 3, an LVG at Bohain on October 9, and a Halberstadt C-type, one of the best ground attack aircraft of World War I, near Ovillers on October 22. He added yet another LVG over Le Quesnoy on October 26 to his tally, and just three days later, on October 29, he destroyed another Fokker D.VII near Mormal. As the Hundred Days Offensive was coming to an end, Beck, on November 1, 1918, scored his final victory over Mormal Woods, again against a Fokker D.VII. It was the last victory claimed by No. 60 Squadron before the World War I armistice was signed on November 11, a closing chapter to a brutal air war, and an extraordinary achievement for a pilot who was still only 18 years old.

By the end of World War I, Alexander Beck shot down 11 enemy aircraft and was promoted to the rank of acting captain and flight commander. In December 1918, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, a prestigious military decoration to honor valor, courage, or devotion to duty while flying in active operations against the enemy. The official statement about his award said that he was “a bold and skillful leader… and [his] personal courage and able leadership have had a marked influence in maintaining the efficiency of the squadron.” In his later life, Beck returned to civilian life, got married in 1937, and owned farms in both Argentina and Lower Heyford in Northamptonshire. His story shares insights into what it meant to be a fighter pilot in World War I, flying open-cockpit aircraft at speeds barely faster than modern cars, and relying on eyesight and instinct. As we launch the Aces series to honor pilots like Captain Alexander Beck, who faced the unknown skies with bravery and skill, follow us for more such articles on Flying Aces.

Related Articles

Kapil is a journalist with nearly a decade of experience. Reported across a wide range of beats with a particular focus on air warfare and military affairs, his work is shaped by a deep interest in twentieth‑century conflict, from both World Wars through the Cold War and Vietnam, as well as the ways these histories inform contemporary security and technology.